The Warner Brothers cartoon character Inki is unique in that he was a recurring African character, as opposed to African Americans like Bosko, Amos ‘n’ Andy, and the maids of “Tom and Jerry” and “Little Lulu.” Appearing in films from 1939 to 1950, Inki also reflected changes in both animation and imagery of the African continent.

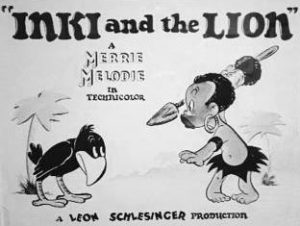

The debut Little Lion Hunter, produced by Leon Schlesinger and directed by Chuck Jones, sets the template for the series. Somewhere in Africa, Inki hunts a mynah who walks to the beat of the song “Fingal’s Cave.” The bird, however, rescues Inki from a lion. Produced during the era of Disney-inspired realism, the backgrounds are lush and detailed. The characters themselves are also detailed with shading or modeling. Charlie Thorsen designed Inki, and the figure sported a black dot for a nose in his debut.

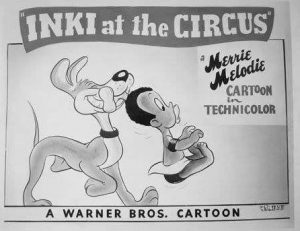

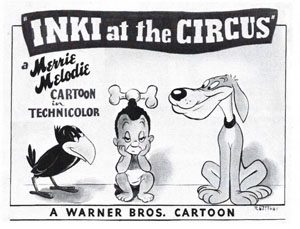

Schlesinger produced two Africa-set sequels for Warner Brothers with the three characters–Inki and the Lion (1941) and Inki and the Minah Bird (1943). Then after Warner Brothers took control of his studio in 1944, the character only appeared two more times and in completely different contexts from the first three episodes. In 1947 Inki at the Circus placed the trio under the big top. Inki was in a cage and billed as an African “wild man.” The opening shot was of circus tents in the foreground and a skyline of skyscrapers and other urban buildings behind them, thus giving the film a contemporary and domestic setting.

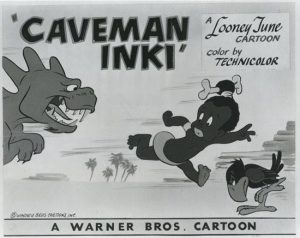

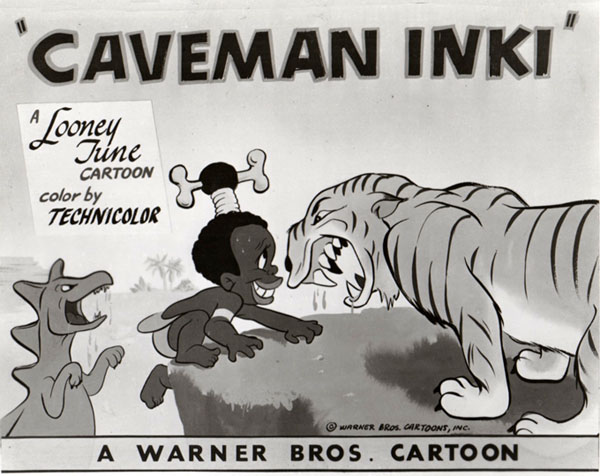

For the finale Caveman Inki (1950), Warner Brothers made Inki primitive in a most literal sense. The boy became a prehistoric figure, living among dinosaurs. By 1950, people had begun protesting ethnic stereotypes in films, and the studio’s moving away from explicitly African settings and towards prehistoric ones seemed to reflect awareness of the protests. Ironically, Inki’s customary bone in the hair and his near-nakedness remained consistent, whether as a contemporary but isolated native or a prehistoric figure. Meanwhile, reflecting the popularity of UPA-type stylization, the characters and backgrounds are less detailed than in Little Lion Hunter. Also, Caveman Inki is notable in that it is one of the first works in popular culture to suggest that the first people were Africans. Compare Inki’s dark skin to the fictional prehistoric figures in Famous Studios’ Pre-Hysterical Man, Warners’ own Pre-Hysterical Hare, and Hanna-Barbera’s The Flintstones.

Inki’s debut was eighty years ago this year. His films have not aged well, especially after the 1950s. However, the series in its entirety shows how Warner Brothers grappled with changing times before abandoning Inki altogether.

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

The mynah bird has had a longer life than Inki himself, appearing in both Tiny Toon Adventures (“Buster and the Wolverine”) and The Sylvester and Tweety Mysteries (“A Mynah Problem”).

The Mynah Bird also appeared in the Animaniacs Goodfeathers segment Bad Mood Bobby.

The Mynah Bird also appeared in “Hobo Bobo” (1947) where, as the narrator explains, gave advice to the little elephant on how to get on the ship set to New York.

I am sure that this will be coyly pointed out by others by the time my post is updated. In CAVEMAN INKI, we do have a Caucasian caveman stirring a pot and getting interrupted constantly, which must mean that the first humans came in multiple races. Intriguingly, because his scenes do not display any particular social status superiority to Inki’s and both are dressed in equally “primitive” attire, this cartoon is giving a very positive image to its viewers that different skin tones ultimately mean nothing.

Overall, I rather enjoy the Inki series. The only disturbing aspect to me is the design of his big lips, reminding me of ol’ minstrel shows. Yes, that “bone-head” get-up is pretty stock cannibal type. Otherwise he is no different than the many assorted pantomime human characters we are familiar with in “chase” cartoons.

Yes, you’re are right..there IS a white caveman there..

That is an interesting point about Caveman Inki. I used to see this cartoon plenty of times on TV growing up and just saw the character as normal and nothing more.

WNEW in New York — which banned the worst of the black stereotype cartoons (as well as many of the World War II-themed ones) well before United Artists “Censored 11” list showed up at the end of the 1960, was still airing the Inki shorts well into the 70s, presumably because none of the gags were based on African-American stereotypes — compare these to Jones’ “Angel Puss” (which could be the most annoying of all the “Censored 11” shorts), and the takes on the two characters were extremely different, since Chuck’s stories asked you to identify and sympathize with Inki, even if he wasn’t in control of anything going on.

(Jones, Maltese and Pierce’s only nod to overt racial stereotyping via characture in the series came at the start of “Inki at the Circus” where the opening posters tout the “African Wild Man” and we pan in on a shadow of what appears to be an African warrior … who is revealed to be Inki, locked in a cage and playing with a yo-yo. The point was the stupidity of the “African Wild Man” stereotype, and at the theater I saw it at in the mid-70s as part of a compilation of Warner cartoons, the reveal produced a sympathetic ‘awww’ from the audience).

At least it worked! That was an interesting way to set that one up.

Stereotypical appearance aside, Inki is just one of those Everyman characters Jones uses so often, whose job is to react silently to the madness around him. He used Porky this way at first, before making him Daffy’s more competent sidekick; similar characters include Conrad Cat, the Bookworm in the Sniffles cartoons, and the nameless man who finds Michigan J. Frog in “One Froggy Evening”. The fact that he’s just an innocent child rather than a buffoonish character probably allowed him to last longer than most black characters from that era; note that none of his cartoons are part of the infamous Censored Eleven. Being mute meant no dated “shuck n’ jive” talk, which likely helped.

The first Inki cartoon seems to be Warners’ answer to Disney’s “Little Hiawatha” the previous year. The setup is similar: a native child acting grown up by going hunting, then being saved from a large predator by the other smaller creatures that took pity on him.

Watching the first three cartoons back to back, you really get a sense of how Jones’ style evolved through the forties. They are basically the same cartoon, down to repeating individual gags, but the approach changes; the pacing becomes tighter, the designs more streamlined, and the gags become wackier. “Inki and the Mynah Bird” even approaches Tex Avery levels of surrealism.

As Chuck Jones told me, “Those cartoons really baffled Walt Disney. They baffled me, for that matter. I just made them because I thought they were funny. I wasn’t even sure they were funny. Walt Disney would run them for his staff and say, ‘What’s so funny about these?’ If he’d brought me over, I couldn’t have told him. They were really fourth-dimensional pictures and I don’t understand the fourth dimension.”

Which I find amusing because the fourth dimension is time, and who is better at timing than Chuck?

I saw all of these, the first four. on Los Angeles’s KCOP-TV. and the one post-48 (non-United Artitsts) package, final one, CAVEMAN INKI, once in 1974 on KTTV(now FOX) in Los Angeles,California. Incidentally, Caveman inki was a tryout at an orchestrations credit.:-)

The Inki cartoons have always fascinated me. I love LITTLE LION HUNTER for its lush visuals, INKI AND THE LION for its score, and MINAH BIRD for its surreal nature.

Mr. Lehman, do you have any insight as to why United Artists didn’t put their Inki shorts on the Censored list in 1968? His basic design surely would have been a red flag. Granted his shorts have more appeal compared to those that were pulled (save for INKI AT THE CIRCUS). I kinda find it surprising that he more or less got an official video of his own in the mid-80s.

I think it’s because Inki was an African. All of the Censored Eleven cartoons contain African American caricatures. Even the cartoons JUNGLE JITTERS and THE ISLE OF PINGO PONGO have Africans or some kind of rainforest inhabitants speak in stereotyped African American dialect or sing like African Americans (the Mills Brothers in the latter film).

It’s utterly baffling how mainstream the Inki cartoons continued to be, well into the 1980s. TBS and TNT used to run them often, and of course Inki shared the spotlight and cover with Tweety on one of the earliest MGM video cassette compilations. Meanwhile, “Caveman Inki” was even featured during the 1990-1992 run of “Merrie Melodies Starring Bugs Bunny and Friends” in syndication.

I saw CAVEMAN INKI in the early ’90s, too.

I have always loved this delightful little mute. I see (nor have i EVER seen) anything “racist” about him. The films are gorgeous! Thank YOU!

Chuck Jones said “I didn’t understand them. Nobody understood them.” So whose original idea was it?

Well, I have to agree that the INKI cartoons were probably not included among the censored 11 titles because all is pantomime and there is no dialogue. However, I just don’t remember ever actually seeing “INKI AT THE CIRCUS” shown at all; ditto for “CAVE MAN INKI”. And what made them interesting for me was the mysterious little sleepy-eyed bird and the musical score which carried most of the cartoon.

One other interesting aspect of these cartoons that was never explored is that, according to wikipedia, the mynah bird could, like parrots, copy the sounds of other animals. I could see this as being part of the comedy of these films, but Jones kept the voices out of the picture entirely.

Then again, no other bird sounds may be needed since practically every jungle live action film and animated cartoon, regardless of the continent it takes place, already has the Australian kookaburra. Listen to the opening of CAVEMAN INKI. Chuck Jones apparently used this sound a couple times, most famously in DUCK AMUCK! The Disney studio used it as well, obviously in THE JUNGLE BOOK.

This article tries its best to chronicle this feathered Australian who managed to go international screen-wise: http://soundandthefoley.com/2013/05/30/that-jungle-sound/ The list here and in a follow-up article is pretty impressive on indeed. The 1935 serial version of THE ADVENTURES OF TARZAN was among the first, although it is “officially” identified in the re-edited 1938 feature version. Afterwards, we get THE WIZARD OF OZ, OBJECTIVE BURMA!, BLACK NARCISSUS, TREASURE OF THE SIERRA MADRE, REVENGE OF THE CREATURE, SWISS FAMILY ROBINSON, CAPE FEAR, RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK, ROMANCING THE STONE, THE LOST WORLD: JURASSIC PARK II… and that is just a few to list here.

Oh, and one minor flaw in almost every cave culture type of cartoon–humans and dinosaurs never inhabited this earth together according to most books on the evolution of life on this planet. The only bit of animation to get this right was Art Clokey’s series of GUMBY episodes in which our little clay boy dreams himself back in pre-historic times to help save a nest of eggs from being eaten by the larger beasts of the day. But, hey, adding people to the mix adds to the comedy.

The first four Inki cartoons were shown on WGN in Chicago throughout the 60’s and into the 70’s. WGN heavily censored Warner Bros. cartoons, but the Inki’s were left intact. I don’t think many people thought of these cartoons as offensive in this highly diverse city during that era. If there were complaints from the audience, I don’t think these cartoons would have been shown.

I would love to know whose idea it was to have the mynah bird walk to the beat of “Fingal’s Cave.” Was it Jones, one of his unit animators, or Carl Stalling? I think that and the mynah himself are the two things that make these cartoons so extraordinarily memorable. I first saw them back in the ’50s, not knowing that the music came from Mendelssohn.

In a 1969 interview, when Michael Barrier asked Stalling whether it was his idea to use the Mendelssohn for the Mynah Bird’s walk, the composer replied: “Yes, and it went over so well we had to use it every time.”

The Hebrides Overture, to give its proper title, was in the repertoire of every silent film organist and was used to convey a mood of awe and mystery, especially in a maritime setting. (“Fingal’s Cave” is an alternate title that Mendelssohn’s publisher gave to a later edition of the work.) Stalling used it often in his scores, for example in “From A to Z-Z-Z-Z”, where Ralph Phillips daydreams about commanding a submarine.

Personally (and I realise I’m probably alone in this), I have never liked the Inki cartoons precisely because I don’t think the Hebrides theme makes a fitting leitmotif for the Mynah Bird. Stalling quotes the overture extensively in the first part of the first Inki cartoon, “The Little Lion Hunter”, but I think it creates the wrong mood for a cartoon set in the African jungle. If Stalling had given the bird a different theme in the same tempo — maybe something balletic, or something elegant like the minuets of Paderewski or Boccherini — the contrast with the bird’s exaggerated seriousness would make for a greater comic effect. These cartoons have their merits, but I don’t find them funny at all — a rare misfire from Stalling, and a much less rare misfire from Jones.

Inki also appeared as a porter in the Jones b/w short “Porky’s Ant” (1941).

It’s wrong (though technically right) to say Leon Schlesinger and Warner Bros. produced these as that implies production of the films was a conscious act on the part of Leon and/or Warner Brothers. Production of the films was not a conscious act. The directors were left on their own to produce whatever they dreamed up. I love the INKI AND THE MYNAH BIRD series. It’s good to see it being written about.

I had a gorgeous 16mm print of LITTLE LION HUNTER in the 1970s. It was wonderful to hear the audience gush over the wonderfully lush use of color in the backgrounds as well as throughout the film.As time passed the color faded. I have wonderful digital copies of those films now. The color does not fade on digital prints. If we know how to use our projectors they still get that awe from audiences. Jones usually limited himself to three in a series. We are lucky he made five in this series.

The freedom Jones and his contemporaries enjoyed is long past. We are not going to see it return.

I never saw an Inki cartoon until the advent of public domain kid videos.

These films, comparatively speaking, are benign, in that the humor comes from the situation, and not because the character is dark-skinned. The “fourth-dimensonal” quality of this series remains fascinating, and Inki is sympathetic to audiences because he attempts the impossible and is playing against a stacked deck of fate. The dead-pan mina bird, who seems tapped into occult forces, is an inspired creation, and the films display Chuck Jones’ growing skill as a director. These cartoons were still running on TBS and TNT in the 1990s. I wish Inki’s appearance wasn’t so typical of the era; Jones seemed to have a blind spot in his depiction of non-white characters in the 1940s, and the dreadful ANGEL PUSS is a permanent black mark on his record, but the Inki series is noteworthy and has artistic merit–unlike the vast majority of the films Christopher Lehman has discussed and will discuss in this series of columns.

Another thing about Caveman Inki,

The final cartoon in which he had starred,

Is that it’s the only entry for Inki,

To have retained its title-card.

I realize I’m a bit late to this, but one thing that has intrigued me about the Inki series was its length when compared to the other short-run series produced by Jones. When looked at from debut to final appearance, the Inki shorts managed to outlast Sniffles, The Three Bears, etc., while also encapsulating the first half or so of Jones’ career at Warner Bros. pretty well:

1939: Animation and backgrounds at the most lush and Disneyesque, with the slow timing and emphasis on ‘cute’ that went with it.

1940: Less detail in the artwork, but still very full. The timing and humor remain very slow and deliberate.

1943: Now in the post-‘Dover Boys’ period, the backgrounds have gone totally abstract with squash-n-stretch animation and surreal, Avery-like gags with much faster delivery.

1947: The animation has been reined in but is still looser than in Jones’ earlier period and the humor and timing grows more sophisticated as the characters are arguably taken well out of their element in the only short not in a jungle setting.

1950: Now we are well into Jones’ golden period, where the animation, gags and timing were at their best. When I first saw this, I found Inki himself ‘cute’ but not in the cloying way as in ‘Little Lion Hunter’ or in the way Jones depicted characters in his later years.

Again, it’s fascinating to me that Inki lasted right up to the start of the 1950s (even though this short was probably done and ready to go by 1949 at the latest). The only other comparable Jones character would be Sniffles, and his last appearance was in 1946. A final Sniffles short released in 1949/50/51 would have proved an interesting companion piece to ‘Caveman Inki’ in terms of Jones’ evolution as an artist.

Another interesting fact

Is that Inki did not change a tad.

Sniffles evolved like Chickenpox,

And turned into quite the chatterbox,

But Inki and the bird remained

More or less unchanged.