Hank Ketcham in the Lantz studio’s Inbetweener room, 1938

Before he became rich and famous as the creator/cartoonist of the Dennis the Menace comic strip, Hank Ketcham was an eighteen-year-old kid freshly arrived in Hollywood. Growing up in Seattle, one of his only professional contacts was someone he knew from high school, Vernon Witt, who had gotten a job at the Walter Lantz studio.

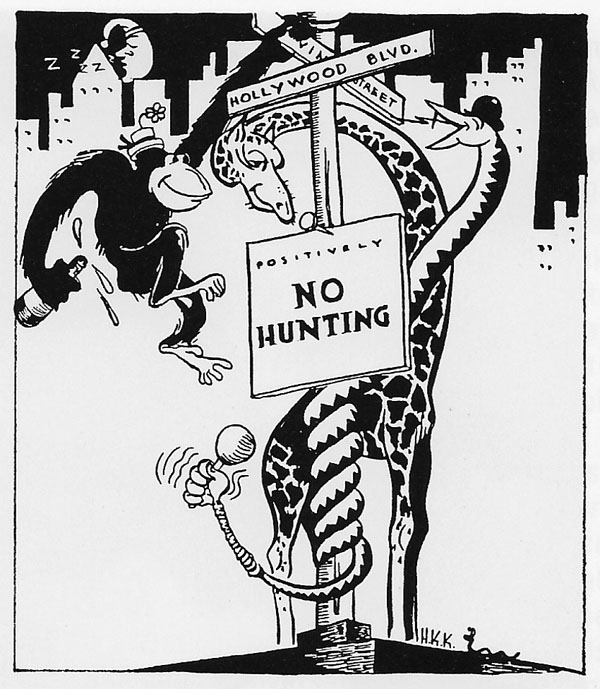

Witt encouraged Ketcham to bring sample drawings to the Universal Pictures lot for a review. Apparently Ketcham didn’t have anything to submit, so he spent all night drawing and carefully inking two samples, one of his first lessons in what would be a lifetime of making deadlines for the Post-Hall Syndicate and then King Features. He even kept the two drawings he made, one of them posted here: his take on the famous Hollywood and Vine intersection.

The interview and review couldn’t have gone better. Witt hired Ketcham on the spot and apologized that because of the tight financial situation, Walter Lantz had only authorized a weekly salary of $16. To young Henry, known as Hank, this was a bonanza, not a setback, and he eagerly accepted. Besides, he was living cheap in a boarding house. Now he was spending his money out on the town, hitting the hotspots around that Hollywood and Vine “zoo” of hipsters and celebrities.

In Ketcham’s autobiography, The Merchant of Dennis, he writes glowingly of his time working at Lantz for fourteen months from 1938-39. He also provides a description of the Inbetween Dept, which is not discussed much by cartoon historians in favor of stronger contributions by directors like Alex Lovy, Rudy Zamora, Les Kline, and Burt Gillett, as well as key staff like Ed Kiechle, La Verne Harding and Milt Schaffer.

He refers to the room where he worked as “the Black Hole at Lantz” which had a staff of eight at that time, including Witt, “Jolly Tolly” Kerchenoff, “Wild Jimmy” Perch, Ben Duer, Dick Kinney, Fred Rice, and Spider Brown, whom he describes as “a stoop-shouldered string bean who shuffled through life wearing a long moth-eaten cloth coat that hung almost to the ground.” For Christmas, Lantz was either generous or despairing of this poor soul and gave Spider Brown a brand new overcoat.

Ketcham reflected on his work there as a “bottom rung job in the animation industry” and says the gang of inbetweeners passed their time working with lots of outrageous chatter, probably obscene, something he hints at when he wrote that the dark room was “understandably off limits to the girls in Ink and Paint” and that his years attending a First Methodist Church “hadn’t prepared me for these new sights and sounds.” Here is a passage from his book describing the job of inbetweening:

“It sounds more tedious and complicated than it really is. In order to guide a pencil between the lines of two other drawings, you slip the thumb and two fingers of your left hand between three sheets of paper in a sort of chopstick grip, enabling you to flip the pages of the action to see the action. Inbetweeners always labor in a darkened room, using a light beneath the glass drawing board to better delineate the sometimes delicate pencil lines they must draw between.”

This is a practice long used by animators, too, requiring the use of both hands. With a pencil in one’s right hand, the fingers of the left hand can be tucked within as many as four sheets of paper, fanning them up and down repeatedly to get a quick glimpse of individual drawings within a sequence. This often results in a sort of dog-eared marking that one finds on the bottom left corner of archival pages of classic animation.

The extreme darkening of this “Black Hole” room suggests that the inbetweeners were also somewhat reliant on the “onion skin” appearance of bottom-lighting that allows one to see down through several layers of paper. This allowed them to draw a number of drawings between the animators’ key poses even without always flipping pages. In contrast, the Animation dept. had regular room lighting.

To read these accounts from Ketcham offers an interesting view of the Lantz studio during a time of transition, when the studio had abandoned Oswald Rabbit, was experimenting with Andy Panda, and had not yet hit upon its greatest success with Woody Woodpecker. On any given day, Ketcham was handed unfinished sequences, marked for timing, from a number of Lantz’s best animators. Ketcham mentioned his opportunity to work for La Verne Harding, the first woman animator at a Hollywood studio.

I wrote about Harding in a recent post, with an emphasis on her own comic strip Cynicial Susie, and it is interesting to speculate what inspiration it may have served for the future creator of Dennis the Menace to work with Harding and perhaps to ask her questions about her own experiences having drawn a daily comic strip for a newspaper syndicate.

Also, as a treat, here’s an archival gag submission from Ketcham from 1938, when the Lantz studio was in the midst of producing five Nellie and Dauntless Dan cartoons. I don’t think this has been seen in over 75 years, and the cartoons themselves have largely slipped into obscurity. This is from a multi-panel strip signed by Ketcham with this description:

Panel 1: “Commentator says—“Here we find Baby Nell” as a big hand (as of commentator’s) reaches and—“ Panel 2: “lifts up the basket. Baby Nell is reading ‘Acrobatics in Three Easy Lessons’ or something similar to it, she looks around—smiles—TAKES—and jumps into the basket, which by now is on the ground.”

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

This is quite interesting. If Tex Avery ever did his own in-betweening, I have to ask, not meaning to entirely veer off the topic, here, just how he was able to do this with one eye’s worth of sight, and I wonder if in-betweening was done exactly the same way at all the major cartoon studios.

Tex was already promoted to animator in 1930, three years before he lost vision in one eye; it resulted in loss of depth perception but did not hold him back from his ability to see clearly what he drew. He certainly achieved a lot with “one eye’s worth of sight.” Also, I’m not certain when the Inbetween dept was first established at Universal, or how much its creation was influenced by practices at Disney. Tex Avery was, prior to the paperclip accident, an inbetweener, but only for a very short time. I’ve never heard that Tex, like Hank Ketcham, ever worked in an isolated dark room. A larger question I’ve wondered about was how Avery and Bill Nolan worked with assistants because Virgil Ross once told me that both eschewed the modern pose-to-pose method that made inbetweening so viable–he said that they were the only two who animated straight-ahead without setting key poses. By the time Ketcham arrived in ’38, though, they were no longer at Lantz and the new post-Oswald era was taking shape, including the hiring of Burt Gillett as a director, who had a considerable number of Disney cartoons to his credit. By that point, Lantz was continuing to make his studio’s production process more in keeping with the rapid innovations at Disney, so I expect that the late 30s saw changes that were motivated by this intent to Disneyfy.

There was a Tolly Kerchenoff and a Tolly Kirsanoff working in animation in 1939? (Kirsanoff made 896 dollars that year).

That spelling was taken from Ketcham’s written account; I’m sure we’re talking about the same Tolly!

Anatole Kirsanoff, one and the same.

The method of rolling sheets of animation paper from the top edge works when the studio uses bottom pegs. If top pegs are used, flipping from the bottom is the preferred method to check motion. Lantz apparently used bottom pegs, as did Disney. Warner Bros used top pegs for decades. Animation camera operators like bottom pegs because they can put down and pull off new drawings much quicker than when top pegs are the name of the game.

Gee, if that’s so, why not punch all paper with four holes: top and bottom? That way everyone’s preference would be served.

Robert Taylor once told me that using top pegs was “The New York Way”. I’ve seen Lantz animation drawings by Bill Nolan from the early 30s that use top pegs, which is not surprising since he’d only left NYC in 1929. So Lantz must’ve switched over to bottom pegs at some point. I’m under the impression top pegs were still predominately used in NYC well through the 1960s though.

I just wanted to be mention that I need to be careful by referring to the “dog-eared bottom left markings” on archival animation paper: I was not exclusively talking about Lantz in saying that, or even the 1930s. It was more of a general reference for readers who may have been unaware of this flipping technique. The Lantz studio in the 30s certainly was using top-pegs. All the animation samples I have seen are registered at the top, and Ed Kiechle’s pan layouts from the late 30s are punched at the top, too. So, in that one comment I made, I didn’t intend to make that broad inference. Just to clarify (unless anyone has strong disputing evidence): Lantz Productions in the 1930s used top-pegging. Ketcham’s reference to his “chopstick grip” with three fingers must have actually been done at the top corner of the pages.

The great Phil Hartman’s Dennis the Menace cartoon was also very good. I believe it was animated by Rankin Bass/Ghibli people. The use of the 1938-39 “Black Hole at Lantz” was probably a pun on “the Black hole of Calcutta” of 1756. Walter Matthau’s character makes a similar reference to a sweltering, dark writers’ room in 1957’s A Face In The Crowd. Physicist John Wheeler wouldn’t coin the term “Black Hole” to describe the celestial phenomena until 1967.