It was twenty-five years ago that a Walter Lantz character made national headlines for what seemed like a mad dash to escape the impending Yuletide stress. During a 1990 Detroit holiday parade, a giant Chilly Willy balloon broke free of his handlers. By the time Santa Claus was brought out to greet the onlookers, the huge penguin had already gusted out over city limits, heading northbound in a cold wind.

He was found later chilling along Walpole Island, actually having crossed over the border into Canada. There is a fun account of that bold escape that you can read here by eyewitness Mark Osler. Even more incredible is that, a few months after capture, this famous fugitive was inflated again for another promotional appearance. His second pratfall, though less publicized, was even more disastrous. The balloon knocked a parade official off the roof of a car dealership.

Why so much spunk and punk, Chilly Willy? The answer it seems can be found if anyone simply watches one of his cartoons. He is single-minded and irascible. It can be hard to look away as he brazenly persists in some quest, usually to find food or warmth. In doing so, he confounds the efforts of another character and reliably drives them to anger or insanity. Surely those good folks back in Detroit were naïve in thinking he would make an ideal parade guest.

Why so much spunk and punk, Chilly Willy? The answer it seems can be found if anyone simply watches one of his cartoons. He is single-minded and irascible. It can be hard to look away as he brazenly persists in some quest, usually to find food or warmth. In doing so, he confounds the efforts of another character and reliably drives them to anger or insanity. Surely those good folks back in Detroit were naïve in thinking he would make an ideal parade guest.

Chilly Willy is, in many ways, a final parting gift from Tex Avery to add another name to an exclusive shortlist—the pantheon of studio characters we remember from the Golden Age of theatrical shorts. And it was very much a generous gift directly to Walter Lantz, who profited so immensely from the enduring appeal, in contrast to Avery who received just a flat sum for his short employment there in 1955, getting on-screen credit as a director for only two Chilly cartoons.

To truly celebrate what Avery bestowed, I want to also recount why he ended his work at Lantz in 1955, a tale that reveals a lot about the workings of Hollywood, as relevant today as it was sixty years ago. Tex at that time was known in the industry as one of the great animation directors, a kingmaker who was most responsible for bringing out the star qualities of Bugs Bunny for Warner Bros. and Droopy for MGM.

Would he be able to repeat this kind of franchise success for Lantz in 1955? We already know the answer to that—Chilly is arguably second only to Woody Woodpecker among Lantz brand names. The knowledge that Tex could deliver this kind of return on investment enabled him to be in negotiation with Walter for more than a high salary. He wanted a share of the profits from the cartoons he was making, something he had never been able to secure working at the major studios.

This story is hearsay, but it is has been carried down in the oral tradition of animators, the sort of thing you heard in the 1990s if you sat down for a drink at The Smoke House with a veteran of Golden Age cartoons. It represents only the opinion of Tex Avery, who shared his frustration with his peers, that he felt Lantz had not initially disclosed an obstacle toward ever seeing an accurate total portion of resulting revenue.

Avery had gotten word that Lantz was financing the purchase of a yacht as a studio expense. There was nothing technically improper with doing so—even today, for instance, studio bosses will travel or entertain in private Gulfstream jets on the company dime—but to Avery the disclosure felt like an insincere gesture or worse. Since he was negotiating a “back-end” deal with Lantz Productions, it meant that studio expenditures like this had to first be squared before profits would be counted toward Avery’s split.

Avery had gotten word that Lantz was financing the purchase of a yacht as a studio expense. There was nothing technically improper with doing so—even today, for instance, studio bosses will travel or entertain in private Gulfstream jets on the company dime—but to Avery the disclosure felt like an insincere gesture or worse. Since he was negotiating a “back-end” deal with Lantz Productions, it meant that studio expenditures like this had to first be squared before profits would be counted toward Avery’s split.

Frustrated, he walked away from negotiations and was paid only salary working so capably as a director, leaving material for subsequent Chilly Willy cartoons that were then completed by Alex Lovy. There are two sides to every story, so it should be mentioned there is also speculation that Avery was paranoid during these discussions. Because twenty years earlier he had pitched a producing deal at Universal that was, in effect, a coup against Walter Lantz’s leadership, it must have been a concern of his that Walter would have an old grudge to quietly settle. There is no reason to think was the case, and as a producer he was widely known to be magnanimous, but the lingering memory of this could have put tension in the room.

The revelation about yacht payments trimming from the bottom line might have been just the kind of validation of his fears that Avery was inclined to suspect. It scared him off. When I once asked Walter about their negotiation in an interview, he insisted that he had offered a very attractive deal on the whole. He felt that Tex Avery was unable to get past some minutiae of their contract and he felt certain that if Tex had worked it out—if he had agreed to Walter’s terms of the partnership—that he too would have gotten rich.

The revelation about yacht payments trimming from the bottom line might have been just the kind of validation of his fears that Avery was inclined to suspect. It scared him off. When I once asked Walter about their negotiation in an interview, he insisted that he had offered a very attractive deal on the whole. He felt that Tex Avery was unable to get past some minutiae of their contract and he felt certain that if Tex had worked it out—if he had agreed to Walter’s terms of the partnership—that he too would have gotten rich.

Probably there will be people who read this anecdote who take sides or make judgments. That has a lot to do with the fact that this kind of story continues to be alive and well in the entertainment industry. It remains a truism that you should always take a “front-end” deal instead of a “back-end” deal, but good luck getting either. There is plenty of money being made in Hollywood, but the studios have never easily shared their wealth with artists. For most of us, success is a measure of getting paid fairly to do what you love. Striking it rich is a luxury.

The sadness of Tex Avery is that he gave up so much more than he should have to leave behind his enormous legacy to cartoons. He was a perfectionist who literally suffered for his art. He lost his vision in one eye, his son died and his marriage began to fail. As he gained weight and his health declined, he grew depressed and withdrew into his craft. Making people laugh with his cartoons must have been a reliable source of comfort and distraction.

The sadness of Tex Avery is that he gave up so much more than he should have to leave behind his enormous legacy to cartoons. He was a perfectionist who literally suffered for his art. He lost his vision in one eye, his son died and his marriage began to fail. As he gained weight and his health declined, he grew depressed and withdrew into his craft. Making people laugh with his cartoons must have been a reliable source of comfort and distraction.

After his death in 1980, his reputation and influence only grew. If only he could have known the second act his fortunes would have taken if he had lived longer to ride across a cartoon Renaissance that so venerated him. As I mentioned in my Halloween post, it should make anyone scream to think of all the years of Avery-directed Lantz classics that we might have today—if only this matter of a studio yacht had not broken up their negotiations.

What if the “Ghost of Christmas Future” had visited Walter in 1955? Would the Ghost be showing him a fifteen year stretch of vintage Chilly Willy that was the envy of every studio? Would Walter and Tex be toasting a mutually rewarding business partnership that gave rise to a prolific and beloved curtain call to both of their storied careers, instead of leaving us with The Beary Family and Kwicky Koala?

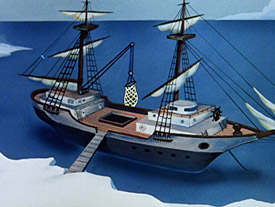

Avery’s penultimate cartoon at Lantz, The Legend of Rockabye Point, is generally regarded as his final masterpiece. And what a spoonful of irony to know that it opens with a zooming shot that brings the audience down on to the deck of a ship. A sea captain says, “Ya hear that singing out there?” On an isolated peak of ice, an old bear sings Rock-a-bye to an aging guard dog. The captain makes known that twenty years earlier, because of this ship, a series of events instigated by Chilly Willy drove them both to this insane, miserable fate.

Avery’s penultimate cartoon at Lantz, The Legend of Rockabye Point, is generally regarded as his final masterpiece. And what a spoonful of irony to know that it opens with a zooming shot that brings the audience down on to the deck of a ship. A sea captain says, “Ya hear that singing out there?” On an isolated peak of ice, an old bear sings Rock-a-bye to an aging guard dog. The captain makes known that twenty years earlier, because of this ship, a series of events instigated by Chilly Willy drove them both to this insane, miserable fate.

It also seems ironic now to remember that runaway parade balloon escaping Detroit. How can we not see the symbolism of it, Chilly busting loose to head north to that frozen peak that exists only in legend? The life and work of Tex Avery can be viewed now as an enormous gift that we enjoy every time we watch his great cartoons. So, in this week after Christmas, let us raise a toast and celebrate him and the penguin he generously set loose on the world.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

To be fair, Tex died during production of Kwicky Koala, so most of his stuff might’ve been tossed out by careless producers.

A local tv station in Los Angeles KCOP 13 had a special tribute to Tex Avery called “Tex Avery: King of Cartoons” that aired after Tex Avery’s death with included a test pilot clip of Kwicky Koala.

Nice remembrance Tom.

Seems Tex had unfortunate personal issues, and I wonder if he might not have been his own worst enemy over time.

I think Chilly Willy would have had more “legs” if he was a Warners character. As superb as the 40s Lantz toons were, the quality drooped (see what I did there) quickly in the mid-50s, with the exception of Tex’s brief stay.

Sometimes success doesn’t happen despite quality or effort.

The big question is: where is the big restored Avery home video box set ? ? ?

When DiC brought out “The Wacky World of Tex Avery” I as well as a lot of people thought it was going to be based on the classic cartoons of Tex Avery but it was a nightmarish Schlepfest that included a character named “Tex” Avery which looks like a doppelgänger of Robert McKinnion’s Red Hot Rider from Bugs Bunny Rides Again. A character named Freddy the Freeloading Fly which was loosely based on Homer the Homeless Flea, a character named Einstone which was loosely based on characters from The First Badman and Pompeii Pete which looked like a reject from Asterix the Gaul. And at the same time Cartoon Network aired The Tex Avery Show which had the classic Tex Avery cartoons from both the WB and MGM library vault as well as his final cartoon Kwicky Koala.

Interesting post! Many accolades have been afforded the memory of Walter Lantz. Just about everyone has gone on record to state that Walter Lantz was a generous, caring employer, and a wonderful guy to work for. He was also a very successful businessman who knew who to keep his own dream together. Money was always tight at the Lantz’s and Walt even closed the studio on several occasions due to financial difficulties. It should be noted that Walt also gave his entire staff vacation with full pay during these episodes to make things a little easier for his “kids”, as he liked to call them.

The voice of the sea captain was Dallas McKennon, who also voiced Buzz Buzzard for Lantz and Gumby for Art Clokey.

Dallas McKennon also voiced Inspector Willowby and did the vosfx for Hercules the Plumber cartoons.

I wonder if Tex had anything to do with Willoughby, who was basically a humanized Droopy.

Legendary animation producer/director Paul Fennell told me of a lunch meeting he had with Walter Lantz during one of the periods when Lantz had to lay off his staff as a dire economic move. Lantz tried to interest Fennell to come on board as a business partner in his studio, complaining to Fennell that he was down to his last 60 thousand dollars. Fennell laughed and replied to Lantz “Shit, Walter, I’m down to my last 6 thousand bucks!” Lantz wasn’t in the mood for levity on the subject and there were no more such meetings with Paul Fennell.

Sad to see that go down like that.

It is hard to picture Walter Lantz as a yacht kind of guy. Leon Schlesinger, though…

Particularly interesting is where Walgreen’s was licencing Chilly Willy for a line of ice creams and other “frozen novelties” a few years back, as sold in their drugstores.

Ironically I found a tiny standee of Chilly Willy used in someone’s outdoor Christmas decorations while on my walk today. I was impressed.

In Mark Arnold’s THINK PINK, there’s a quote from Tex Avery about his time at Hanna-Barbera: “This is where us old elephants go to die.” Very saddening and heartbreaking to think about.

I wonder if Tex really got to appreciate the body of work that he gave us. It has been said that Avery grew to hate his characters, especially SCREWY SQUIRREL; I guess I understand why, as it seemed to me that so many animators wanted to achieve so much more than we fondly remember them for, but yes (sigh), as someone said above, now, we can’t even honor Tex Avery’s body of work with a completest box set of all his classic cartoons, TV spots and other even rarer things that only avid collectors are aware of and we have only heard whispers of.

I have a copy of the French Tex Avery, and is is missing two cartoons, Uncle Tom’s Cabana, and Half Pint Pygmy. Also, A few are edited. I would be nice to have a full blown release here.