In this anniversary year of both Fantasia and Fantasia 2000, we take a Spin through a stack of recordings inspired by Mickey Mouse’s classic clash with bewitched brooms.

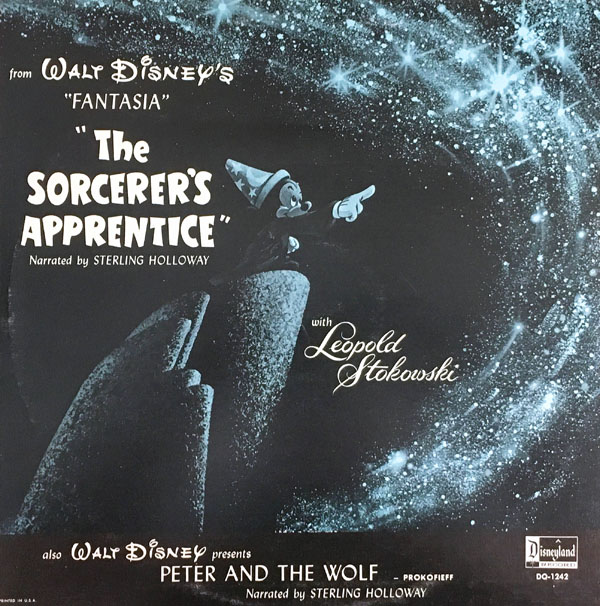

From Walt Disney’s “Fantasia”

THE SORCERER’S APPRENTICE

Narrated by Sterling Holloway

Music by Paul Dukas

Conducted by Leopold Stokowski

Disneyland Records WDL-3016 (Side Two Only / 12” 33 rpm / Mono / 1961)

LP Reissues: WDL-3016 (1960); DQ-1242 (1964); ST-3926 (1964, with Magic Mirror book); ST-3926 (1969, with regular Storyteller book)

2044 CD Reissue: DQ-1242 (Wonderland Music Company Music-on-Demand Theme Park Edition, 2004)

(All of the above are paired with Peter and the Wolf)

2015 CD Reissue: D-002066392 (Bonus material on “Fantasia Legacy Collection” Set)

Originally Released April 3, 1958. Executive Producer: Jimmy Johnson. Producer: Camarata. Music Recorded at the Pathé Studio, Culver City.

Running Time: 10 minutes.

No other single recording of Walt Disney’s version of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice has seen more repackagings, reissues or sheer longevity than this Sterling Holloway gem, located on side two of a Disneyland album from 1957 featuring Peter and the Wolf on side one.

Sterling Holloway’s voice acting career is as cherished by Disney enthusiasts as his appearances in vintage movies are by film buffs. Whether seeing or hearing Holloway, one has to smile. (We paid further tribute to this Disney Legend closer to his January birthday in this Spin.)

For the album, producer Tutti Camarata used the mono soundtrack of the Stokowski orchestral performance and a script was prepared to match the action. The album adaptation is uncredited, but it is possible that Holloway himself worked on the script. He did receive a credit for the 1960 LP, The Grasshopper and the Ants (see this Spin). Holloway was under contract to Disneyland Records may have, at the very least, made contributions to the narrative. The variations in tone are perfect, as it matches Mickey journey from timidity to daring, panic to relief.

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice is the nucleus of what Fantasia became, according to the famous story of a meeting between Walt Disney and Stokowski in which Walt suggested The Sorcerer’s Apprentice for Mickey. Among the reasons for the idea, aside from its inherent ingenuity, is Mickey’s career needing a boost. Donald Duck was not only becoming more popular, but Mickey had become so iconic that it had smoothed out whatever edge he once had. The role of the Apprentice was perfect for Mickey as “an actor” in that he was allowed to (gasp!) misbehave but pay a price, and in doing so run a gamut of challenging emotions.

As luck would have it, our own Jim Korkis recently wrote extensively on the making of FantaSound. [Among the many details is the meeting with Walt and “Stoki.” Jim’s writing always surprises me with new facts, among them that Jon Favreau specifically wanted a “FantaSound” effect for the Dolby Atmos in-theater system used in his 2016 version of The Jungle Book — a remake that he said was intended to sit alongside the original, not replace it. That he made so many such efforts in the making of that film says a lot about the director and the resulting film.

When the Fantasia soundtrack was given the deluxe “Walt Disney Records Legacy Series” album treatment with the custom illustrations and historic data, this recording was added as a bonus, so it is currently available as a pristine CD and as a download.

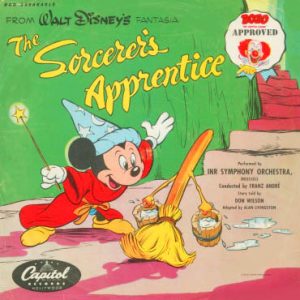

From Walt Disney’s “Fantasia”

THE SORCERER’S APPRENTICE

Told by Don Wilson

Music by Paul Dukas

The Brussels Symphony Orchestra

Capitol Records – Children’s Series DBS-3094 (10” 78 rpm / Mono)

LP Reissues: J-3251 (1961); Ziv-Wonderland L-8110 (1978)

Originally Released in 1952. Producer/Writer: Alan W. Livingston. Conductor: Franz Andre.

Running Time: 11 minutes.

“Oh, Don!” was the familiar call of one of the world’s best-loved entertainers, Jack Benny, when this amiable announcer was needed on the long-running radio and television comedy/variety show. Don Wilson is also immortalized in animation history as the narrator of Walt Disney’s Oscar-winning Ferdinand the Bull. (He narrated Ferdinand for Capitol Records too. More about that here).

“Oh, Don!” was the familiar call of one of the world’s best-loved entertainers, Jack Benny, when this amiable announcer was needed on the long-running radio and television comedy/variety show. Don Wilson is also immortalized in animation history as the narrator of Walt Disney’s Oscar-winning Ferdinand the Bull. (He narrated Ferdinand for Capitol Records too. More about that here).

Don Wilson is an excellent children’s narrator because he has the standard announcer’s baritone of the mid-20th century, but even without the visual, he adds joviality and warmth to even the darkest moments of a tale.

A tightly descriptive style is used for this, the debut children’s recording of Walt Disney’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. It is as if writer/producer Alan Livingston (who produced all the Capitol children’s records) saw the film and took notes, or perhaps viewed storyboards. Specific on-screen movements are described in this version that are not mentioned in the Holloway script. It is less of a commentary than a vivid recounting. Neither approach is necessarily better than the other, but the comparison is interesting.

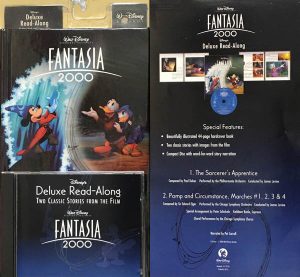

Walt Disney Pictures Presents FANTASIA 2000 Deluxe Read-Along

Two Classic Stories from the Film

THE SORCERER’S APPRENTICE

POMP AND CIRCUMSTANCE, Marches #1, 2, 3, 4

Narrated by Pat Carroll

Music by Paul Dukas and Sir Edward Elgar

The Philharmonia & Chicago Symphony Orchestras & Chorus

Walt Disney Records – Children’s Series DBS-3094 (10” 78 rpm / Mono)

LP Reissues: J-3251 (1961); Ziv-Wonderland L-8110 (1978)

Released in 2000. Executive Producers: Roy E. Disney, Don W. Ernst. Producers: Randy Thornton, Ted Kryczko. Music Producer: Jay David Saks. Conductor: James Levine. Soprano: Kathleen Battle. Special Arrangement: Peter Schickele.

Running Time: 11 minutes (Sorcerer’s Apprentice); 7 minutes (Pomp and Circumstance).

Roy E. Disney received no album credit when he wrote the script for the Disneyland Records Bambi Storyteller album (see this Spin), but Fantasia 2000 was his project through and through, even to the detail of this wonderful–and perhaps little-known–read-along package. It combines a hardcover read-along book, illustrated with stills from the feature, and a compact disc with the two most kid-friendly segments: The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (starring Mickey) and Pomp and Circumstance (starring Donald and Daisy).

Roy E. Disney received no album credit when he wrote the script for the Disneyland Records Bambi Storyteller album (see this Spin), but Fantasia 2000 was his project through and through, even to the detail of this wonderful–and perhaps little-known–read-along package. It combines a hardcover read-along book, illustrated with stills from the feature, and a compact disc with the two most kid-friendly segments: The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (starring Mickey) and Pomp and Circumstance (starring Donald and Daisy).

Making this even more of a one-of-a-kind treasure is the presence of Pat Carroll as the narrator. Like Jodi Benson voicing Ariel, Carroll does not takes her position as the voice of Ursula lightly and proudly performs the role for other projects outside The Little Mermaid. It’s the crowning touch on a decades-long career on Broadway, films and hit television shows. There was a time when Pat Carroll was a welcome and frequent presence on talk and game shows. She’s earned immortality.

Except for a few minor changes, her narration for The Sorcerer’s Apprentice is adapted directly from the 1957 Sterling Holloway recording. What a gift it is to have a chance to hear another veteran performer interpret the clever script in a new way! And because Carroll is not playing the villainess Ursula but instead storytelling as herself, there is a feeling of a close neighbor, friend or relative telling you the stories as if she can’t wait to see if you love them as much as she does.

GREG EHRBAR is a freelance writer/producer for television, advertising, books, theme parks and stage. Greg has worked on content for such studios as Disney, Warner and Universal, with some of Hollywood’s biggest stars. His numerous books include Mouse Tracks: The Story of Walt Disney Records (with Tim Hollis). Visit

GREG EHRBAR is a freelance writer/producer for television, advertising, books, theme parks and stage. Greg has worked on content for such studios as Disney, Warner and Universal, with some of Hollywood’s biggest stars. His numerous books include Mouse Tracks: The Story of Walt Disney Records (with Tim Hollis). Visit

Personally I feel that the narration just gets in the way of Dukas’s musical storytelling, which is quite vivid enough without it. But of the three, I think Pat Carroll gives the best performance.

Only the Capitol Records recording uses the complete, original version of the piece. Stokowski made a lot of little cuts in it, mostly repeated phrases: three bars here, gone; half a dozen there, good-bye. I first saw Fantasia when I was eighteen, by which age I was already familiar with my parents’ Toscanini recording of “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” and had played it in youth orchestra, so I was very conscious of the cuts; they’re most noticeable in the passage where Mickey is showing the broom how to fetch water.

These cuts may have been made at the behest of Disney and his storymen. On the other hand, Stokowski was known for taking extreme liberties in his interpretations, far more than any conductor today would do, so that might just have been the way he ordinarily conducted “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice”. When I was young I had a recording of Stokowski conducting Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture and Romeo and Juliet, and he took several cuts of this kind (Tchaikovsky’s transitional passages have a fair amount of fat to trim). Most notable was that Stokowski cut the entire ending of Romeo and Juliet, getting rid of the crescendo in the timpani and the final big closing chords, so that the piece faded out on a peaceful B major chord. I rather liked it, even if it wasn’t what Tchaikovsky wrote.

Stokowski’s cuts notwithstanding, I think that “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” in Fantasia is the finest ten minutes of film the Disney Studio ever created.

Thanks, Paul. You add so much, a lot of musical specifics that I don’t know and add so much to our understanding and enlightenment.

Fantasia was no stranger to controversy for several reasons, among them that the music was conformed to the needs of the film, and perhaps to Stokowski’s interpretations, as you noted. I like to think of it as a movie soundtrack first and a set of classical pieces second, with the actual, more accurate performances available on other recordings. Thanks for pointing out that the Capitol version was closer to the original Dukas than the other two, which were the 1940 and 2000 soundtracks.

Budget-wise, for a children’s record, it would be expensive to hire an orchestra, so Capitol either picked up an existing Brussels Symphony recording or outsourced it to save money. Most recordings of Sorcerer’s Apprentice (and other classical pieces) made specifically for children’s labels used library recordings.

Thank you, Greg. Just a dew words about Paul Dukas: He lived at a time when French composers generally fell into one of three opposing factions: the conservatives, led by Saint-Saens; the romantics, led by Cesar Franck; and the impressionists, led by Claude Debussy. Dukas didn’t belong to any faction yet was respected by all of them. He made his living mainly as a music critic but was especially critical of his own work, abandoning or destroying most of his compositions for failing to meet his high standards. Apart from “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice”, his surviving works include one symphony, one opera, one ballet, a couple of overtures, a piano sonata and some other piano music — and that’s about it. Great stuff, but unfamiliar to most concertgoers. Dukas is thus one of the few great composers who with some justice may be described as a “one-hit wonder”. But what a wonderful hit!

Many thanks, Greg, for giving a “shout out” to my article on FantaSound. For those who want to read it, here is the link:https://www.mouseplanet.com/12667/What_Was_Fantasound And, in addition, I would also like to say that your articles are always filled with new information I never knew. I always feel smarter after reading an article by Greg Ehrbar. We miss you here in Orlando but glad you are happy and doing well in Los Angeles.

Thanks, Jim. That’s always so nice. I miss the folks back in Florida and think about everyone and the memories all the time. What a history we all lived through! Sorry I didn’t get your link in the text–I usually link like crazy. I might add that the info about the recording location came from your article too. I knew that Sorcerer’s Apprentice was not performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra but not the specifics. The record albums correctly credit Stokowski and do not mention the Philadelphia Orchestra (Tutti knew his stuff, too).

This proves, different strokes for different folks, because, unlike Paul, I love the narratives. I love it when the conductor introduces the selection they are about to play with a story of what’s happening. In my early days, one orchestral rendition of any selection was all you needed. Boy, did that ever change. I soon discovered that each conductor and orchestra delivered dramatically different interpretations. Their personalities, arrangements, and availability of instruments make every selection they play unique. Some performances are flat while others are vibrant. Sometimes you wonder if each conductor and orchestra have the same sheet music. Even some great conductors like Leonard Bernstein, (who I love) recorded some duds. Do people ever give Walt the credit he deserves for bringing music into our lives? I owe it all to Walt? He knew how important music was to movies and that music was a lead character. “Fun with Music” and “Tubby the Tuba” were my 1st and favorite records as a little boy. I wore them out.

I agree that it’s good when conductors, and performers in general, establish a connection with the audience by speaking to them directly, instead of maintaining a sacerdotal aloofness as in bygone days. But there’s a world of difference between that and talking while the music is playing.

You’re quite right about conductors and their differing interpretations. I own two recordings of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony: one, with John Eliot Gardiner conducting the Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique, clocks in at 59 minutes; the other, with Carl Boehm conducting the Vienna Philharmonic, lasts 78. If you played both of them at the same time, starting together and gradually going out of phase, Gardiner would reach the final double bar before Boehm’s singers had even stood up for the finale!

I grew up with Leonard Bernstein’s recordings and treasure the score to Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony that he autographed for me when I was fifteen. He also did some great televised concerts for young people. But some of his interpretations — I hesitate to call them “duds”, but they were certainly controversial. One of my colleagues was in the BBC Symphony Orchestra when Bernstein made his notorious recording of Elgar’s Enigma Variations in 1982, taking the “Nimrod” variation at an agonisingly slow tempo. He tried to inspire the musicians by telling them, quite flippantly, to think of the British warships heading to the Falkland Islands; the war was very controversial, and his remark, especially coming from a foreigner, struck them as in exceedingly poor taste. He also smoked during the recording session, and nobody tried to stop him. By the time it was all over, everybody in the orchestra despised him. The list of composers whose music Bernstein conducted better than anyone else is a very long one, but Elgar does not belong on that list.

Neither does Wagner. Bernstein went on a Wagner kick in the 1970s, and he was the first conductor to take over twenty minutes to do the Prelude and Liebestod from “Tristan und Isolde” (besting the previous record holder, the aforementioned Carl Boehm). When I was in music school Bernstein was going to come in and do a reading of that piece with the orchestra, but he didn’t show up, and later a representative apologised and said he had been ill (read: hung over). One year my parents gave me the “Bernstein Conducts Wagner” LP for Christmas, and his tempos were so slow that I could only enjoy the music if I played the record at 45 rpm. To this day the Prelude to “Die Meistersinger” sounds funny to me, because I got used to hearing it in F major instead of C!

One of the engineers who worked on the Fantasound project, Howard Tremaine, later became the editor of the Audio Cyclopedia, a thick reference handbook for sound engineers that was in print from the late 1950s to the early 1980s. Within the Audio Cyclopedia, Tremaine contributed a lengthy article on the Fantasound system, complete with photos. Used copies are available online, but go for crazy money. The 1987 and later editions are complete rewrites and Tremaine’s contributions are nowhere to be found.