I asked in an earlier column, “How much of what everyone ‘knows’ about animation history is wrong?” This week’s column will look two more widespread animation myths. Here’s the first:

The Warner Bros. cartoons were so great because studio bosses Leon Schlesinger and Eddie Selzer took no interest in them, and had no idea what their animators were turning out.

This myth is attributable directly to WB director Chuck Jones. He said so. He should know, shouldn’t he?

Leon Schlesinger (1884-1949) worked in East Coast movie theaters in his youth, and later moved to “Hollywood” where most of the cinema industry was. In 1919 he founded Pacific Title and Art Studio in Burbank, to make title cards for silent movies. In 1930, he was contacted by Rudolph Ising and Hugh Harman from a team of movie animators who had been making the “Oswald, the Lucky Rabbit” cartoons for producer Charles Mintz, who sold them to Universal Pictures. (Mintz had earlier hired the animators away from Walt Disney, who had created “Oswald” for Universal.) Universal had just fired Mintz and taken over producing the “Oswald” cartoons with its own studio, headed by Walter Lantz. Mintz had closed his studio and let all his animators go. Instead of dispersing, Ising & Harman persuaded them to stay together long enough to see if they could sell their services as a complete animation studio to someone else. Ising & Harman offered their services to Pacific Title & Art. Schlesinger, who could see the disappearance of movie title cards with the introduction of sound films, in turn offered the services of an animation studio to Warner Bros., the last major motion picture producer that did not have a cartoon department. WB hired him, and Schlesinger hired Ising & Harman and the former Mintz animators as Leon Schlesinger Studios. In 1934, after a dispute with Ising & Harmon, the two left Schlesinger taking their cartoon star Bosko with them. Schlesinger quickly hired back most of the other animators plus some from other studios, and arranged with WB to set up his own studio on the WB lot, later dubbed “Termite Terrace” by the animators. (Schlesinger sold Pacific Title & Art Studio in 1935 to concentrate on his animation studio. PT&A is still in business as a general post-production house for the movie and TV industries.)

Leon Schlesinger (1884-1949) worked in East Coast movie theaters in his youth, and later moved to “Hollywood” where most of the cinema industry was. In 1919 he founded Pacific Title and Art Studio in Burbank, to make title cards for silent movies. In 1930, he was contacted by Rudolph Ising and Hugh Harman from a team of movie animators who had been making the “Oswald, the Lucky Rabbit” cartoons for producer Charles Mintz, who sold them to Universal Pictures. (Mintz had earlier hired the animators away from Walt Disney, who had created “Oswald” for Universal.) Universal had just fired Mintz and taken over producing the “Oswald” cartoons with its own studio, headed by Walter Lantz. Mintz had closed his studio and let all his animators go. Instead of dispersing, Ising & Harman persuaded them to stay together long enough to see if they could sell their services as a complete animation studio to someone else. Ising & Harman offered their services to Pacific Title & Art. Schlesinger, who could see the disappearance of movie title cards with the introduction of sound films, in turn offered the services of an animation studio to Warner Bros., the last major motion picture producer that did not have a cartoon department. WB hired him, and Schlesinger hired Ising & Harman and the former Mintz animators as Leon Schlesinger Studios. In 1934, after a dispute with Ising & Harmon, the two left Schlesinger taking their cartoon star Bosko with them. Schlesinger quickly hired back most of the other animators plus some from other studios, and arranged with WB to set up his own studio on the WB lot, later dubbed “Termite Terrace” by the animators. (Schlesinger sold Pacific Title & Art Studio in 1935 to concentrate on his animation studio. PT&A is still in business as a general post-production house for the movie and TV industries.)

Schlesinger’s own offices were not in the ramshackle animation building, which helped to create a feeling of separation between the animators and management. The animators have told similar stories about Schlesinger looking in upon them briefly occasionally, and saying approximately, “How are you boys doing? Is everything okay? Well, keep up the good work.” The plump Schlesinger, who wore an obvious toupee, reeked of cologne, and dressed nattily in a white suit, made no secret that he considered himself above his working-man animators. He owned a yacht, often spent all day at the horse races, and commented aloud about the Termite Terrace workshop, “I wouldn’t work in a shithole like this.” This increased the animators’ willingness to make fun of him.

But it was good-natured fun. Rather than not caring about the animators except for the money that their cartoons brought in, most of the animators agreed that Schlesinger kept a close eye on his studio and deliberately gave them maximum creative freedom. His attitude, openly expressed, was, “I pay you boys to make funny cartoons. As long as the public likes your work and you stay within budget, you can do whatever you think will bring in the laughs.” Schlesinger jovially agreed to not only let his animators make a Christmas gag reel in 1939 and 1940, he participated in them. Schlesinger also agreed to star in a combination live-action/animated short directed by “Friz” Freleng, You Ought to Be in Pictures (May 1940), playing himself as the head of his studio with Porky Pig and Daffy Duck (animated) unhappy with their contracts. Other Schlesinger employees also appear in You Ought to Be in Pictures, including writer Michael Maltese as a WB studio guard, and Henry Binder, Schlesinger’s executive assistant, as a stagehand.

After Ising and Harmon left, it was Schlesinger who put Friz Freleng in charge of his studio, and hired such animators as Tex Avery, Bob Clampett, Frank Tashlin, and Chuck Jones, and voice artist Mel Blanc and musician Carl Stalling. According to animation historians, it was Schlesinger who made the final decision to name Bugs Bunny. The character had already become a favorite at the studio among the animators, and was unofficially known as “Bugs” from being labeled as “Bugs’ Bunny” on a model sheet for Ben “Bugs” Hardaway, the first director to use him. In 1940 Tex Avery directed A Wild Hare, the first cartoon where the rabbit would have to have a name. Avery called him Jack Rabbit. (Mel Blanc said it was Happy Rabbit.) The rest of the cartoon’s animators wanted to make the Bugs Bunny name official. The argument grew so heated that both sides took it to Schlesinger to decide. Schlesinger said Bugs Bunny, definitely. It was already in use by most of the animators; it was a more striking name than the generic Jack Rabbit; and it fit the smart-alec personality of the rabbit. The disappointed Avery quit and went to MGM. It was also Schlesinger who named Bob Clampett’s notorious Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs. Clampett intended to name it So White and de Sebben Dwarfs, but Schlesinger worried that that was too close to Disney’s original.

After Ising and Harmon left, it was Schlesinger who put Friz Freleng in charge of his studio, and hired such animators as Tex Avery, Bob Clampett, Frank Tashlin, and Chuck Jones, and voice artist Mel Blanc and musician Carl Stalling. According to animation historians, it was Schlesinger who made the final decision to name Bugs Bunny. The character had already become a favorite at the studio among the animators, and was unofficially known as “Bugs” from being labeled as “Bugs’ Bunny” on a model sheet for Ben “Bugs” Hardaway, the first director to use him. In 1940 Tex Avery directed A Wild Hare, the first cartoon where the rabbit would have to have a name. Avery called him Jack Rabbit. (Mel Blanc said it was Happy Rabbit.) The rest of the cartoon’s animators wanted to make the Bugs Bunny name official. The argument grew so heated that both sides took it to Schlesinger to decide. Schlesinger said Bugs Bunny, definitely. It was already in use by most of the animators; it was a more striking name than the generic Jack Rabbit; and it fit the smart-alec personality of the rabbit. The disappointed Avery quit and went to MGM. It was also Schlesinger who named Bob Clampett’s notorious Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs. Clampett intended to name it So White and de Sebben Dwarfs, but Schlesinger worried that that was too close to Disney’s original.

Tom Sito, a veteran animator and animation historian, and President of the Motion Picture Screen Cartoonist’s Local 839 (animation’s professional labor union) from 1992 to 2001, commented on a 2008 Cartoon Brew story about Schlesinger’s obituary, “Many Termite Terrace vets who disparaged Leon’s leadership, all admit what Leon was best at was keeping the meddling suits from the main lot from annoying the artists with their “creative” opinions. We could use a lot more Leon Schlesingers today. Leon also was a champion of his animation unit and once complained to the Academy that Disney won the short film Oscar too many times.”

More pertinently, was Daffy’s and Sylvester’s juicy lisp copied from Leon Schlesinger’s, and was Schlesinger ignorant of this? Maybe, maybe not. Besides Jones in Chuck Amuck, cartoon writer and gag man Michael Maltese is quoted in Joe Adamson’s Tex Avery: King of Cartoons (Popular Library, 1975) as saying that Schlesinger lisped “a little bit”: “But we were not hampered by any front office interference, because Leon Schlesinger had brains enough to keep the hell away and go aboard his yacht. He used to lithp a little bit and he’d say, ‘I’m goin’ on my yachtht.’ He’d say, ‘Whatth cookin’, brainth? Anything new in the Thtory Department?’ He came back from Mexico once, he had huarachas on, he said, ‘Whaddya think of these Mexican cucarachas? Very comfortable on the feet.’ He said, ‘Disney can make the chicken salad, I wanna make chicken shit.’ He said, ‘I’ll make money.’” (pgs. 125-126) Blanc might have based his lisp for the duck’s and the cat’s speech on Schlesinger’s, and exaggerated it to such an extent that Schlesinger did not recognize it as based on his own lisp – or even if he did, he may have recognized that Blanc exaggerated it so outrageously that it was funny. Schlesinger has shown that he could go along with a gag. Basically, by the time Chuck Amuck: The Life and Times of an Animated Cartoonist (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1989) was published, Schlesinger was long dead, Clampett was recently dead, and most people didn’t care. Jones’ story was too good not to repeat. The scenes of Schlesinger in You Ought to Be in Pictures and the 1939 & 1940 gag reels (embed below), where Schlesinger’s real voice is heard, although very brief, do not hint of any lisp on the sound track; though arguably, Schlesinger could have deliberately concentrated on not lisping since he knew that he was talking on camera.

In 1944, Schlesinger sold his animation studio to Warner Bros. and retired. WB officially made the studio its cartoon department, and assigned Edward Selzer (1893-1970) to replace Schlesinger. Selzer, whom everyone agreed was more humorless and formal than Schlesinger, deliberately continued Schlesinger’s policy of giving the animators creative freedom as long as they stayed within the increasingly smaller budgets.

Jim Korkis said here in his Animation Anecdotes #107, posted on April 26, “Animation legend Chuck Jones was always fond of telling the story of his meeting with Jack and Harry Warner of Warner Brothers Studio. ‘Friz Freleng and I had a meeting with the two of them. We were taken to the private executive dining room. Jack looked over at us and said, with a mouthful of food, ‘You know, I don’t even know where our animation studio is.” Harry nodded and said, ‘The only thing I know about our cartoon studio is that’s where we make Mickey Mouse’. They didn’t realize we didn’t make Mickey Mouse. When they finally found out, they closed the studio.’”

Jim Korkis said here in his Animation Anecdotes #107, posted on April 26, “Animation legend Chuck Jones was always fond of telling the story of his meeting with Jack and Harry Warner of Warner Brothers Studio. ‘Friz Freleng and I had a meeting with the two of them. We were taken to the private executive dining room. Jack looked over at us and said, with a mouthful of food, ‘You know, I don’t even know where our animation studio is.” Harry nodded and said, ‘The only thing I know about our cartoon studio is that’s where we make Mickey Mouse’. They didn’t realize we didn’t make Mickey Mouse. When they finally found out, they closed the studio.’”

Ha ha; very funny! As for being true … Well, all of the biographies of Jack Warner do agree that he ruthlessly concentrated on the studio’s live-action features only, and dismissed the cartoons as worth making only because theater-owners wanted them as part of a complete theatrical package. The WB facilities were huge, and in 1953 the cartoon department was at WB’s Sunset Boulevard lot, not the main Burbank lot; so maybe Harry and Jack Warner didn’t know exactly where it was. But Jack kept track of whether the cartoons stayed profitable or not, and it was Eddie Selzer’s job to see to it that they did.

(On the other hand, one of Harry Warner’s other well-known comments, in 1927, was, “Who the hell wants to hear actors talk?”, in response to Sam Warner’s support for making The Jazz Singer. Fortunately for the world, Sam Warner won that argument – and died the day before the movie’s premiere.)

What Jones did say, on page 89 of his Chuck Amuck autobiography, was, “Friz Freleng contends that the Warner brothers implicitly believed we made Mickey Mouse, until 1963 – when, shocked to discover that we did not, they shut the studio.” Oh, so it’s Friz Freleng’s story now. By 1963 Harry Warner was dead – he died in 1958 – so it was Jack’s decision alone to close the animation unit. The reason given by the studio was the increasing production costs of animation, plus falling orders from theater-owners who by the 1960s felt that audiences no longer demanded a cartoon with their feature. That is a more believable reason than that Jack Warner had just found out that WB did not make the Mickey Mouse cartoons.

The two stories that seem verified to Selzer’s discredit are about Selzer ordering Freleng not to team up Tweety with Sylvester – Wikipedia says, “Some historians also claim that Friz Freleng nearly resigned after butting heads with Selzer, who did not think that pairing Sylvester the cat and Tweety was a viable decision. The argument reached its crux when Freleng reportedly placed his drawing pencil on Selzer’s desk, furiously telling Selzer that if he knew so much about animation, he should do the work instead. Selzer backed off the issue and apologized to Freleng that evening.” — and that, after director Robert McKimson made the first cartoon featuring the Tasmanian Devil, Devil May Hare in 1954, Selzer ordered him not to made any more because he was afraid that audiences would dislike the ferocious Taz. It was not until Jack Warner personally told Selzer that the Devil was getting “boxes and boxes” of fan mail, and should reappear in the cartoons as soon as possible, that Selzer greenlit Taz’s further appearances. And those are not among Chuck Jones’ stories. Jack Warner does not look so ignorant of WB’s animation there, as long as it pertained to the studio’s overall income.

One story that Jones does tell about Eddie Selzer in Chuck Amuck is, on page 93, “He once appeared in the doorway of our story room while Mike Maltese and I were grappling with a new story idea. Suddenly a furious dwarf stood in the doorway: ‘I don’t want any gags about bullfights, bullfights aren’t funny!’ Exactly the words he had used to Friz Freleng about never using camels. Out of that dictum came Sahara Hare, one of the funniest cartoons ever made, with the funniest camel ever made.

Having issued his angry edict, Eddie stormed back to his office. Mike and I eyed one another in silent wonderment. ‘We’ve been missing something,’ Mike said. ‘I never knew there was anything funny about bullfighting until now. But Eddie’s judgment is impeccable. He’s never been right yet.’ ‘God moves in wondrous ways, his story ideas to beget,’ I replied. Result: Bully for Bugs – one of the best Bugs Bunny cartoons our unit ever produced.”

Now, let’s see. Eddie Selzer, their boss and an angry man with no sense of humor, had just ordered them to never make a cartoon about bullfighting; and had previously issued a similar order about camels. Both times, his animators had immediately disobeyed his orders. Are we to believe that, if this had happened at another studio, Walt Disney’s maybe, that the boss would not have instantly fired those employees? Maybe Jones meant this to serve as an example of how little Selzer kept track of what went on in his studio. A cartoon short, from every studio, took months to produce; and when it was completed, everyone including especially the producer viewed the finished product. Are we to believe that Selzer remained ignorant of the camel and the bullfighting cartoons all during this time? It is more probable that Selzer was aware of and continued Schlesinger’s managerial practice: give the staff complete freedom to be as funny as they can, as long as they stay within budget. Also: WB released Bully for Bugs on August 8, 1953. Sahara Hare was not released until March 26, 1955. Was Freleng over two years in production of Sahara Hare, or was Jones less than accurate in his reminiscing?

Here’s this week’s other myth…

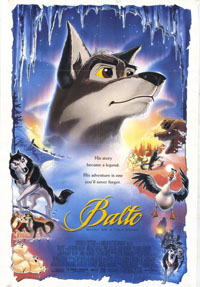

Balto was the lead sled dog of the team that brought the diphtheria serum to Nome, Alaska in 1925.

This myth is not particularly animation-related, but it was the basis for three animated features; the Balto 1995 theatrical feature by Steven Spielberg’s Amblimation studio, and the direct-to-video sequels, Balto II: Wolf Quest (2002) and Balto III: Wings of Change (2004), both produced by Universal Cartoon Studios. So it seems worth covering here.

It is “true, but”. In January 1925, Doctor Curtis Welch, the only doctor in Nome, Alaska, isolated by the winter season, discovered that a diphtheria plague was breaking out. The nearest antitoxin was in Anchorage, almost a thousand miles away. No airplane was available. The closest that a train could get was the town of Nenana, 304 miles from Anchorage and still 674 miles away. The only way to transport the serum to Nome in time was by dog sled. The 674-mile journey was made by not one, but several Siberian husky sled dog teams. Relay teams were organized by radio from Nome and from Nenana. The two would meet at Nulato, a halfway point, where the Nenana team would hand the serum to the Nome team for the return journey.

The teams from Nenana faced -50º F temperatures and lower in blizzard conditions. Several dogs died. The last sledder, Henry Ivanoff, decided to go past Nulato to save the Nome team some time. The Nome team was led by sledder Leonhard Seppala, and his lead dog was Togo, named for the Japanese admiral who had won the 1905 Battle of Tsushima. Seppala was travelling through a storm with a wind chill factor of -85º F. It took him four days to reach the point where Ivanoff was, and he would have passed him in the storm if Ivanoff had not called out. Seppala took the serum and turned back to Nome immediately. (There had been seven deaths when he left, and over twenty more confirmed cases.)

The teams from Nenana faced -50º F temperatures and lower in blizzard conditions. Several dogs died. The last sledder, Henry Ivanoff, decided to go past Nulato to save the Nome team some time. The Nome team was led by sledder Leonhard Seppala, and his lead dog was Togo, named for the Japanese admiral who had won the 1905 Battle of Tsushima. Seppala was travelling through a storm with a wind chill factor of -85º F. It took him four days to reach the point where Ivanoff was, and he would have passed him in the storm if Ivanoff had not called out. Seppala took the serum and turned back to Nome immediately. (There had been seven deaths when he left, and over twenty more confirmed cases.)

Seppala and Togo travelled back across a frozen sound with ice breaking up. He was met en route by Charlie Olsen, who took the serum but was blown off the trail by the storm and suffered extreme frostbite. Olsen made it to where Gunnar Kaasen’s team led by Balto was waiting. Kaasen took the serum the rest of the way to Nome. They did pass through some horrific conditions – visibility was so poor that Kaasen could not see his closest sled dog, and he also developed frostbite – but they were relatively fresh when they pulled into Nome. The waiting press hailed Kaasen and Balto as the team who brought the serum from Nulato, or all the way from Anchorage. Seppala and Togo, who had covered the longest and most dangerous distance, were recovering from extreme exhaustion and frostbite at the time. Togo recovered first, and escaped to hunt reindeer. By the time he returned to his kennel, Kaasen and Balto were on the publicity circuit; being praised by the press, President Coolidge, and the U.S. Senate.

Seppala and Togo got plenty of recognition later on. They toured the U.S., and in New York’s Madison Square Garden, Togo was given a gold medal by the Swedish explorer Roald Amundsen. But Balto kept getting the greater publicity. There is a statue of Balto in New York’s Central Park, and Cleveland’s school children raised enough money to buy him. He lived the rest of his life in the Cleveland Zoo, and is stuffed and mounted today in the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. And there are three animated movies, – fantasies – but who cares? – to keep his memory alive.

Balto never had offspring; he had been neutered as a young dog. Togo became so popular as a stud dog that most working huskies in the U.S. today are his descendants. Seppala sold the rest of his team to a dog breeder, so today’s American huskies who are not descendants of Togo are likely to be descendants of his teammates.

Here’s a nice piece about it from The History Channel.

Fred Patten (1940-2018) was an internationally respected comics and animation historian. He has written about anime or comic books for publications ranging from Animation Magazine and Alter Ego to Starlog. He was a contributor to The Animated Movie Guide (2005), and is author of Watching Anime, Reading Manga (2004, Stone Bridge Press), a collection of his best essays, and Funny Animals and More (2014, Theme Park Press), based upon his early columns here on Cartoon Research. He passed away on November 12th, 2018.

Fred Patten (1940-2018) was an internationally respected comics and animation historian. He has written about anime or comic books for publications ranging from Animation Magazine and Alter Ego to Starlog. He was a contributor to The Animated Movie Guide (2005), and is author of Watching Anime, Reading Manga (2004, Stone Bridge Press), a collection of his best essays, and Funny Animals and More (2014, Theme Park Press), based upon his early columns here on Cartoon Research. He passed away on November 12th, 2018.

So much has been said about Jack Warner’s indifference to theatrical short subjects and, yet, that studio made more of them and made them better than any other studio. MGM spent more money on theirs, but made fewer… and pretty much stopped altogether (apart from Tom & Jerry); I think only the cheap Traveltalks and Pete Smith Specialties were still going after 1949 apart from some CinemaScope experiments. Columbia was prolific and their comedy unit was their trophy, but they also made a lot of junk as well. Paramount was as chaotic with theirs as they were with their cartoons (i.e. the Fleischer Era vs. the Famous Studios Era is reflected in their other shorts). Yet the live-action shorts bearing the WB shield were just as good as the cartoons: the Melody Masters were among the greatest jazz music shorts ever made, the travelogues of Andre de la Varre and others invite comparison to the later National Geographic TV specials, the Joe McDoakes are STILL funny to watch today, more Technicolor shorts were made by WB than anybody else (2-color in large numbers by 1929, 3-color by ’34) and, while not every title was a classic, so much of the Vitaphone product made in Brooklyn in the ’20s and ’30s was first rate. Yes, Hal Roach and Columbia had the best comedies in the ’30s and Warner’s took a little longer to find their mojo there, but they still aped the competition in the documentary and musical field. I think when studio bosses acted as if the shorts were “no big deal”, it was because they were so confident in them that they assumed the product could speak for itself. Bugs Bunny was clearly a gold mine on TV right from the beginning, although Jack was pretty stupid to sell off the older product for quick cash after he booted his brother in 1956. (Oh well… at least they got it all back by taking over Turner many decades later.)

Of course, you folks can correct me on anything I got wrong here, being this is all about “how much of what everybody ‘knows’ is wrong”… ha ha!

Seems like all the people in the Warners toon department were just a tad cuckoo!That’s probably why their product was so good!

Or it was the people in the Warners toon department who were the most cuckoo who were recognized by Schlesinger and rose to directorial positions.

Despite not getting as much recognition, Togo certainly ended up having a better life in the end then Balto did.

I like to think they were both equal in at least getting to live full lives, though no doubt Togo took home the prize simply for still being a father anyway. I wouldn’t mind an animated take on Togo’s life if it ever came to that, but fat chance one may ever show up.

I still wonder what Selzer’s exact quote was regarding bullfighting cartoons (if he really had made such a demand).

Was he saying simply that bullfights in general aren’t funny? If so, then…. he has a point.

If he said that cartoons ABOUT bullfighting aren’t funny, what in the world provoked that? Was it Davis’ short “Mexican Joyride”?

The building that was Termite Terrace, at 1351 N. Van Ness Ave. in Los Angeles, still stands today. It’s in disuse currently.

Christopher Cook – No , the building dubbed “Termite Terrace” was a separate building from the main Schlesinger studio located at 1351 N. Van Ness . The “Termite Terrace” building no longer exists.

http://books.google.com/books?id=diKnDBs0wrIC&lpg=PA227&ots=9hvpR2HE3y&dq=schlesinger%20studio%20van%20ness&pg=PA227#v=onepage&q=schlesinger%20studio%20van%20ness&f=false

Ah. Mea culpa. Thanks for clearing that up.

Supposedly Avery quit over censorship of his The Heckling Hare (1941), and looking at the cartoon it’s clear that the original ending (supposed based on the punchline of off-color joke, which was not by itself offensive) has been excised. Avery continued to make Bugs Bunny cartoons through 1940 and ’41, which would indicate that he was not upset by the name.

That story of what was cut from The Heckling Hare and why, and that Avery left the studio as a result, is another myth, and it’s not quite true. Read this: http://www.whataboutthad.com/2012/12/15/the-heckling-hare-problem/

So much information on animation fan sites is apocryphal – especially when it comes from eyewitnesses themselves! Often these “print the legend” stories can be corrected with research – like yours – and other times just a knowledge of Hollywood reality in general is enough to make these stories highly suspect.

Another myth that seems to be making the rounds is that the Warner Cartoon department was composed of people who had been fired from Disney. I know that Harman, Ising, and Stallings had LEFT Disney, but otherwise, is there any truyh to that?

None that I know of. The first WB (really Schlesinger’s) animators were those he got as a package deal who had been Charles Mintz’s, who were unemployed as the result of Mintz shutting down his studio — not quite the same thing as Mintz firing them. Mintz got them by hiring them away from Disney without Disney’s knowledge; not at all the same thing as being fired by Disney.

Thank you Fred for answering my message! It’s nice to know I picqued somebody’s interest in my ramblings!

A story Chuck Jones told a UCSC class in the 70s:

A producer — forgot who he named, if anyone — would notice animators flipping through stacks of drawings and didn’t seem to know or care what they were doing. One day, trying to look necessary at a recording session, he picked up a musical score and flipped the pages exactly as the animators did, finally nodding approval and setting it down.

Were there any beloved studio producers, beyond maybe Walter Lantz? Even Disney’s disciples admit he was a tough boss, as driven by his personal vision as others were driven by bottom line.

I think that Chuck Jones told that story about Ray Katz, who was Schlesinger’s production assistant or some executive title — not an animator. He was only about twenty years old at the time, and obviously to the animators very inexperienced.

For what it’s worth, Snopes.com put up a page debunking Mel Blanc’s supposed allergy to carrots.

Nitpick though, they claim the rumor has been around since 2008…. it’s actually bee around for DECADES.

“He lived the rest of his life in the Cleveland Zoo, and is stuffed and mounted today in the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. And there are three animated movies, – fantasies – but who cares? – to keep his memory alive.”

That’s the only thing you can say about that film (and it’s off-shoots). They knew a good road to travel I suppose. I recall my mom even bothered ordering that film one night when it was out on Pay-Per-View around ’96 and wasn’t sure why she did so but I guess she saw something in that story I didn’t. Of course had I known what both Balto and The Lion King did to a generation of fans, I might’ve stayed out of it altogether! It really did inspired an interest in drawing dogs, wolves and anything else for those aspiring artists and authors as much as The Lion King showed a template for it’s group. Both films were very instrumental in my opinion.

For an unrelated side note, I reminded myself of a book adaptation of Balto’s story written by Seymour Reit that was later adapted into an episode of a 15 minute program aired on public TV stations during school hours in the 70’s featuring an artist drawing pictures based on the actions in the story but leaves at a critical point as so the viewers might be interesting enough to pick up from there had they gone to the library to find that title. Of course if you’re home sick in bed watching these things, it wouldn’t matter either way, you just weren’t going to go to that trouble anytime soon.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G1xa6vzInC8

My guess is that selzer overheard jones and Maltese hashing out the bullfight story, poked his head in the door and said bullfights aren’t funny, and they joked to each other that they must be on the right track and continued with what they were doing.

Clearly, from the story about Warner himself supposedly not knowing that Disney, not he, made Mickey Mouse, chuck became quite the teller of tall tales (liar) in his later years.

I guess it’s one of the Percs of outliving your colleagues: you get to rewrite history.

Frank Capra Spent the last years of his life traveling to college campuses and making up all sorts of stories about his movies, and oddly enough all of them were self serving.

The Central Park statue of Balto features prominently in the film, “Six Degrees Of Separation” starring Stockard Channing, Donald Sutherland and Will Smith.

Balto was voiced by Kevin Bacon.

Coincidence?

😉

We never grow tired of that one!

D’oh! And here I thought I had an original thought…and there’s not even a guarantee that this one is. Phooey.

No, the Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon thing has been around as long as this movie was, at least what I remember of it, wanting to find the perfect way to fit Balto into it.