IF Walt Disney seemed complacent to let Max Fleischer have his day in the sun, he had good reason. Despite all the hoopla and hullabaloo surrounding Gulliver’s Travels, Walt knew he had an ace in the hole.

IF Walt Disney seemed complacent to let Max Fleischer have his day in the sun, he had good reason. Despite all the hoopla and hullabaloo surrounding Gulliver’s Travels, Walt knew he had an ace in the hole.

Disney knew that, in order to follow up on the success of Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs, he’d have to have something with a good story line and good songs to go with it. And, even when he put Bambi on a back burner, he kept it simmering while he worked on the little wooden poppet’s adventures.

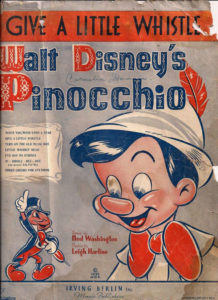

Disney also knew that marketing the picture meant marketing songs as well.

Following a practice he’d done with Ferdinand the Bull, he decided to use songs to market the picture several months before the picture was to hit theaters.

So, during August and September, 1939, several bands were encouraged to play and record three songs that wound up either not being used in the picture, or else were buried in the underscore, where most folks wouldn’t notice them.

“Honest John”, “Monstro the Whale” and “Jiminy Cricket” would wind up being given to bands that were not the hottest swing groups. Instead of going to top-flight swing bands such as Benny Goodman or Tommy Dorsey, or to up-and-comers such as Artie Shaw or Glenn Miller, these songs went to solid name-bands, often trying to be all-around dance or show bands, or to obscure swing groups.

The biggest names to get these early songs were Horace Heidt (who got “Jiminy”) and Kay Kyser (who got both ‘John” and “Monstro”). Both were show bands, and both had gained popularity on the radio. Both bands sported a goodly number of vocalists within their personnel.

Other bands that got these numbers were veteran bands whose leaders had been active for years. Abe Lyman (“John”) and Ted Weems (“John” and “Monstro”) had both been leading bands since the early 1920’s. In the lesser-swing-band category would be Eddie deLange, who drew “Jiminy Cricket”. DeLange had become known as an arranger,and also tried his hand at dong a preponderance of novelty numbers.

By the time the movie was actually in theaters, the real song-plugging began, with songs that actually got into the picture–with the earlier publications almost forgotten.

And the bands that got to do these numbers were more like name bands–including one that was near the top of the polls at the time, both in “swing” and “sweet’ categories. Glenn Miller was a very big name by 1940, and they could have hit with an arrangement of the telephone directory–that’s how big they were! Miller got ‘Give A Little Whistle”, and it sold about as well as any of them at the time.

Hal Kemp, who had a sweet band that could also swing, also got “Whistle’, coupling it with “I’ve Got No Strings”. Meanwhile, Sammy Kaye–whose band was tallied up as a corny “sweet” band, if ever there was one–got to do the big ballad,”When You Wish Upon A Star” and “Turn On The Old Music Box”.

There were also occasional vocal, or “vocadance” records of songs from the “Pinocchio” score. The Four King Sisters got to do “Give A Little Whistle”. Chick Bullock (hose vocalist of the 1930′, still trying to hang on) got to chirp on “When You Wish Upon A Star”. And Buddy Clark, a busy radio singer would wold achieve stardom before dying in a plane crash in 1949, got to do several “Pinocchio” songs for he indifferently-recorded Varsity records, including one that escaped almost everybody, “Three Cheers For Anything”.

Even Victor Young got into the act. As he had with Gulliver’s Travels, Victor Young produced an “album” of songs from the “Pinocchio” score. Not only did he include a satisfying performance of “Three Cheers For Anything”, but even included “Jiminy Cricket” from the first group of songs mentioned above. Ostensibly, the Ken Darby Singes replaced he Max Terr Choristers–although some, upon listening, might find the two groups nearly identical.

Hard to believe that Pinocchio did not turn a profit on its initial theatrical release. (It had to wait until a 1945 theatrical reissue, and it’s been in the black ever since). But the songs were heard about and abroad, and “When You Wish Upon A Star” became the virtual theme song of the whole Disney empire.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

“Jiminy Cricket,” “Honest John,” and “Monstro the Whale” were never intended to be sung in the film. They were written, published, and recorded purely as “exploitation songs,” to be used in the publicity campaign for the film. However, as James suggests, at least two of them (“Honest John” and “Monstro”) can be heard briefly in the instrumental score. “Three Cheers for Anything” *was* supposed to be a vocal number in the film, but was cut during production — although, again, a brief snippet can be heard in the instrumental score.

For what it’s worth, Glenn Miller’s recording of “When You Wish Upon a Star” is also very nice. It was recorded in January 1940, about a month before the film’s premiere — i.e. before the song became extremely well known — and vocalist Ray Eberle bungles the lyrics at one point.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but isn’t that Perry Como singing on “Monstro”?

He was a singer with the Ted Weems band in the late 30s

Male vocalist on “Monstro” is Red Ingle. Red often got the novelty numbers, when they didn’t go to Elmo Tanner as a singer (rather than as a whistler).. per Parker Gibbs.

Como got the romantic stuff.

Famed UK crooner Al Bowlly also recorded WHEN YOU WISH UPON A STAR and TURN ON THE OLD MUSIC BOX for HMV with the Maurice Winnick band.

Was Pinnochio the only Disney feature that had accompanying exploitation songs?

I’d love to find out about any others there might be.

i have the same book how much it worth

I have very old song books from Crosby to Bob hope from the 30s u can call me at 561 667 9566 Mariano