Decades after the public first saw their work, it was captured on audio recordings (along with classic music from Tom and Jerry cartoons) to draw attention to its unique artistry.

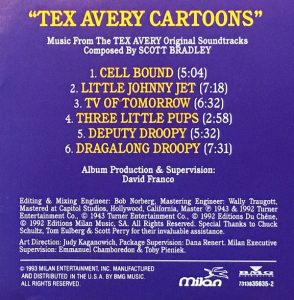

TEX AVERY CARTOONS

Music from the Tex Avery Original Soundtracks

Composed by Scott Bradley

Milan Records 731138-35635-2 (Remastered & Enhanced Mono) Compact Disc

Released in 1993. Producer: David Franco. Milan Executive Supervisor: Emmanuel Charmboredon, Toby Pienick. Editing/ Mixing: Bob Norberg. Engineer: Wally Traugott. Art Direction: Judy Kaganowich. Package Supervision: Dana Renert. Running Time: 36 minutes.

Voices: Daws Butler, Bill Thompson, Joe Triscari.

Scores (music and SFX only): “Cellbound” (1955), “TV of Tomorrow” (1953), “Deputy Droopy” (1955).

Scores (with dialogue): “Little Johnny Jet” (1952), “The Three Little Pups” (1953 / excerpt), “Drag-A-Long Droopy” (1954).

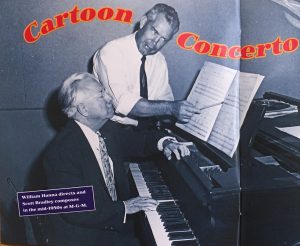

Scott Bradley took pride in creating music for cartoons. “Scoring cartoons is a lot of fun,” he once said. “We get to thinking of these little characters as human beings who believe in ‘direct action,’ and the world that needs a few laughs in the midst of so much suffering.”

Scott Bradley took pride in creating music for cartoons. “Scoring cartoons is a lot of fun,” he once said. “We get to thinking of these little characters as human beings who believe in ‘direct action,’ and the world that needs a few laughs in the midst of so much suffering.”

Animation fans of the late twentieth century saw the great music of cartoons slowly make its way onto home turntables, CD players and recently music files. The Disney library was generous but far from comprehensive, the Hanna-Barbera “HBR” cartoon series brought the unmistakable cues of Hoyt Curtin, Ted Nichols, Jack de Mello and others to vinyl, the important Carl Stalling Project discs made the miracles of Warner musical audio accessible, among a few others.

There remain several studios and composers, like Winston Sharples and Philip Scheib, for which the world is still waiting. But in the ‘90s, a single disc of Scott Bradley music came down from the heavens in a 1993 disc from the Milan label with Tex Avery’s name on the front cover.

The Milan CD came along just after the book, Tom and Jerry: The Ultimate Guide to Their Animated Adventures was published in France (1987) and the U.S. (1990). Author Patrick Brion wrote the liner notes for this CD and participated in the 1988 documentary, Tex Avery: The King of Cartoons, which appears as a special feature on the superb new Blu-ray and DVD release, Tex Avery Screwball Classics, Volume Two (which this author has enjoyed watching several times already).

“I remember when I was just casting about, trying to locate any musical material from the cartoons, how it was much harder to come by this stuff. At the time this CD was it,” said longtime colleague Daniel Goldmark, Ph.D., Head of Popular Music Studies at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio. “This was one of the few things out there, certainly one of the few things dedicated to MGM short subject animation.”

Bringing such classic material to audio is just as challenging as bringing to video. A small company, Milan must not have been able to license more than six cartoons. They were also limited to the scores created specifically for the cartoons and only public domain songs, which resulted in the editing of most of the published popular songs. A few remain, including “Broadway Rhythm” and “Sweet and Lovely,” but most are free and clear like “The William Tell Overture.” Only about half of The Three Little Pups survived the approval process, but along with Drip-A-Long Droopy, it was never released on CD other than on this album.

On the “up” side, three cartoons are free of dialogue with only sound effects remaining and the delightful soundtrack of the others, like Little Johnny Jet, are presented in their final mixes with its wonderful Daws Butler voice performance intact. The mono tracks were not distorted or rechanneled in any way for stereo effect, but they were given a slight reverb and “opened up” just a tad for clarity. They did the very best they could with what they had so we could have a treasure we would not have had otherwise.

On the “up” side, three cartoons are free of dialogue with only sound effects remaining and the delightful soundtrack of the others, like Little Johnny Jet, are presented in their final mixes with its wonderful Daws Butler voice performance intact. The mono tracks were not distorted or rechanneled in any way for stereo effect, but they were given a slight reverb and “opened up” just a tad for clarity. They did the very best they could with what they had so we could have a treasure we would not have had otherwise.

Hearing the audio of a Tex Avery cartoon without the wildly inventive visuals invites the listeners to pay more attention to what Bradley accomplished, how his music differed from other animation composers and the contrast between the “Avery Bradley” and the Hanna-Barbera Bradley.”

“Bradley always worked with economy,” said another esteemed colleague, animator/historian Mark Kausler. “I think he always refused to work with an orchestra with greater than 18 or 19 musicians. Of course, Carl Stalling had the whole Warner Brothers orchestra with about 40 pieces. Stalling’s cartoons sound richer musically. Bradley did great things with only 18 or so pieces. He had wonderful trumpets and trombones and a small but great string section. It’s tough to tell, but that it’s not a much bigger orchestra.”

“Drag-A-Long Droopy”

This is one of two selections that are exclusive to this disc.

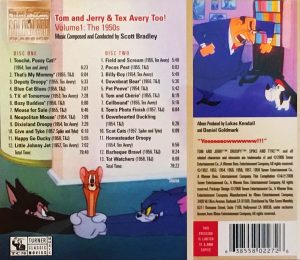

TOM AND JERRY & TEX AVERY, TOO!

Volume 1: The 1950’s

Music Composed and Conducted by Scott Bradley

Film Score Monthly Volume 9, Number 17 (Stereo / *Mono) Two Compact Discs

Released in 2006. Executive Producer: George Feltenstein. Producers: Daniel Goldmark, Lukas Kendall. Liner Notes: Daniel Goldmark. Orchestrations: Scott Bradley. Remix: Michael McDonald. Mastering: Doug Schwartz. Art Director: Joe Sikoryak. Production Assistant: Jeff Eldridge. Additional Images: Michael Barrier, Bob Burns, Photofest. Special Thanks: Mike Barrier, Rebecca Bodner, Tim Curran, Ned Comstock, Nick Corsello, Noni Ellison, Alexander Kaplan, Jonathan Z. Kaplan, Dave Kapp, Mark Kausler, Leonard Maltin, Mark Pinkus, Bill Rush, Keith Scott, Craig Spaulding, Richard Steele, Keith Zajic. Running Time: 159 minutes.

Voices include: Françoise Brun-Cottan, Shug Fisher.

Tex Avery Scores: “Deputy Droopy” (1955), “TV of Tomorrow”* (1953), “Dixieland Droopy”* (1954), “Little Johnny Jet,”* (1952), “Field and Scream”* (1955), “Billy Boy”* (1954), “Cellbound” (1955), “Homesteader Droopy”* (1954).

Tom and Jerry Scores (Hanna and Barbera): “Touché, Pussy Cat!” (1954), “That’s My Mommy” (1955), “Blue Cat Blues”* (1956), “Busy Buddies” (1956), “Mouse For Sale”* (1955), “Neapolitan Mouse” (1954), “Happy Go Ducky”* (1958), “Pecos Pest”* (1955), “Downbeat Bear” (1956), “Pet Peeve” (1954), “Tom and Chérie” (1955), “Tom’s Photo Finish”* (1957), “Downhearted Duckling”* (1954), “Barbeque Brawl”* (1956), “Tot Watchers”* (1958).

Spike and Tyke Scores (Hanna and Barbera): “Give and Tyke”* (1957), “Scat Cats”* (1957).

When the aforementioned Daniel Goldmark, also the author of Tunes for ’Toons: Music and the Hollywood Cartoon (and who worked with this author on several Rhino Records cartoon albums and The Cartoon Music Book, which he co-edited), was working at Rhino Records, he got to know many of the people who made the new and improved MGM/Tom & Jerry/Avery soundtrack CD set possible.

When the aforementioned Daniel Goldmark, also the author of Tunes for ’Toons: Music and the Hollywood Cartoon (and who worked with this author on several Rhino Records cartoon albums and The Cartoon Music Book, which he co-edited), was working at Rhino Records, he got to know many of the people who made the new and improved MGM/Tom & Jerry/Avery soundtrack CD set possible.

“You were just not getting the full effect of Bradley’s work on the Milan CD,” he said. “I can only guess at how much Bradley might have been disappointed that the only evidence of his output, where you could hear his music, not only was buried with the dialogue and sound effects but that they were cartoons for Avery, who he didn’t like composing for in the first place. We knew that, this time, we had to get this music out there, we want to hear it in as unobstructed a way possible.”

Nine of these selections offer the “who would have believed it was possible” opportunity to hear them from open to close. There are no sound effects at all and only three short, signature instances of voice work (like “Maria, Mari (O Marie)” from Neapolitan Mouse and Uncle Pecos’ crucial “Froggy Went a-Courtin;” song). The other soundtracks in crisp, clear mono.

The higher budget allowed for more cartoon soundtracks in their entirety, as well as more popular songs like “I’ve Got a Feeling’ You’re Foolin’” from Broadway Melody of 1936; “Over the Rainbow” from The Wizard of Oz; “You Wonderful You” from Summer Stock; and “The Atcheson, Topeka and the Santa Fe” from The Harvey Girls.

Scott Bradley had done some scoring for live-action features and shorts. He composed the entire score for the 1950 Red Skelton comedy, The Yellow Cab Man, but he was mostly assigned sequences calling for his previous work. Like Carl Stalling, who was uncredited for the coffee billboard sequence in the 1945 Jack Benny classic The Horn Blows at Midnight, Bradley scored forest and animal scenes in MGM’s Courage of Lassie (1946) and of course, Tom and Jerry’s swim with Esther Williams in 1953’s Dangerous When Wet.

Scott Bradley had done some scoring for live-action features and shorts. He composed the entire score for the 1950 Red Skelton comedy, The Yellow Cab Man, but he was mostly assigned sequences calling for his previous work. Like Carl Stalling, who was uncredited for the coffee billboard sequence in the 1945 Jack Benny classic The Horn Blows at Midnight, Bradley scored forest and animal scenes in MGM’s Courage of Lassie (1946) and of course, Tom and Jerry’s swim with Esther Williams in 1953’s Dangerous When Wet.

Veteran soundtrack producer/historian Lukas Kendall, who not only founded the indispensable Film Score Monthly magazine and website but through its label has helped bring many of the greatest soundtracks of the long and recent past to disc, was a catalyst for the Avery project. (Kendall also produced the Courage of Lassie soundtrack in a CD set called Lassie Come Home: The Canine Soundtrack Collection.)

“After I left Rhino, I stayed in touch with Lukas about it,” added Goldmark. “We had been batting it around for a couple of years until about August of 2005 when he said, ‘We have nine of these cartoon soundtracks in stereo. There are portions of some others. Let’s see what we can find. We know we have the nine, and if we can flesh it out with others for which we have portions, great.’

“After I left Rhino, I stayed in touch with Lukas about it,” added Goldmark. “We had been batting it around for a couple of years until about August of 2005 when he said, ‘We have nine of these cartoon soundtracks in stereo. There are portions of some others. Let’s see what we can find. We know we have the nine, and if we can flesh it out with others for which we have portions, great.’

“I don’t think there was ever the idea that we were going to try to do something along the lines of The Carl Stalling Project CDs, where Greg Ford with Hal Willner created montages of all these great bits. That really makes sense—especially considering the number of times I’ve listened to them, I can sing those tracks to you, I’ve heard them so many times—for Carl Stalling and Warner Brothers. But Bradley’s style was more ‘through-composed.’

“What set the Tom and Jerrys apart from the some of the Warners, or Bradley from Stalling—and if you’ve read my books you know these are both ‘my guys’—is that they talk a lot more in Warner cartoons and that’s one of the reasons the Stalling Project was so revelatory. Stalling is doing all these ninety-degree turns—we do this, then we do this, and we do this, and so on. Ten genres of music in thirty seconds. Nobody anywhere was doing that.

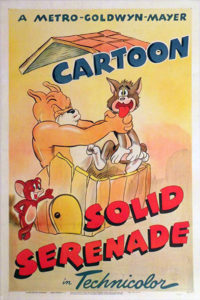

Bradley’s did similar stuff, too, but he was far more through-composed. One of the best examples, though it’s not on the CD set, is Solid Serenade, with the song ‘Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby.’ There’s a part where he’s taunting Spike. The music is ‘Runnin’ Wild.’ Jerry leaves the screen with Tom right behind him. As Tom catches up to Jerry, Jerry is about to untie Spike. There’s the sound effect of the brakes, and the music completely takes that turn from Jerry’s playful little theme to a totally different direction. Bradley can do that, but he could also do all kinds of other crazy stuff—experiments with modern music, his interest in Bartok and Schoenberg—it’s all coming through there.”

Bradley’s did similar stuff, too, but he was far more through-composed. One of the best examples, though it’s not on the CD set, is Solid Serenade, with the song ‘Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby.’ There’s a part where he’s taunting Spike. The music is ‘Runnin’ Wild.’ Jerry leaves the screen with Tom right behind him. As Tom catches up to Jerry, Jerry is about to untie Spike. There’s the sound effect of the brakes, and the music completely takes that turn from Jerry’s playful little theme to a totally different direction. Bradley can do that, but he could also do all kinds of other crazy stuff—experiments with modern music, his interest in Bartok and Schoenberg—it’s all coming through there.”

The FSM CD set allows listeners to compare and contrast a Tex Avery cartoon score with a Hanna and Barbara score even though at first they sound similar. Actually, Bradley was not especially fond of Avery’s use of music, as the great director repeatedly requested what the composer felt were obvious old folk tunes and less of what Goldmark calls “through-composed” music.” Most likely to him, it was less of a challenge and more “wah-wah-wah-wah.”

“It was all punch lines,” explained Goldmark. “Not only was it all punch lines, but he wanted the same old corny tunes again and again which would drive him crazy.” As a rule, Bradley preferred composed original melodies overusing existing tunes altogether, but if he was going to interpolate a song, he was happier when it was a pop, blues or classic piece.

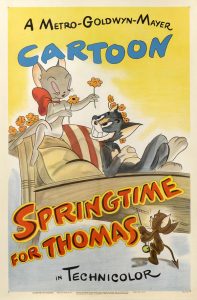

“The song, ‘Lovely Lady’ was a favorite of Bradley’s,” said Mark Kausler. “He used it in Springtime for Thomas, beautifully orchestrated. But I guess my favorite musical moment in a Tom and Jerry cartoon was in The Bodyguard. Tom is trying to get Jerry to chew gum so he can’t whistle for the bulldog to protect him. Bradley uses ‘You’re a Sweetheart. It’s sort of a swing arrangement but beautifully orchestrated with these sweet strings that Scott Bradley weaves through it. So great.

“This is such ironic scoring because the idea is kind of gross slapstick. Tom paints a gumball with glue, which makes Jerry’s jaws all stuck together so he can’t whistle. So the premise is very cartoony and slapsticky, yet Bradley plays ‘You’re a Sweetheart’ behind it. It’s my favorite musical idea in its juxtaposition.”

“This is such ironic scoring because the idea is kind of gross slapstick. Tom paints a gumball with glue, which makes Jerry’s jaws all stuck together so he can’t whistle. So the premise is very cartoony and slapsticky, yet Bradley plays ‘You’re a Sweetheart’ behind it. It’s my favorite musical idea in its juxtaposition.”

Conspicuous by its absence on both Avery soundtrack collections is anything from the Riding Hood cartoons. Milan used an illustration of Red and the Wolf, perhaps in hopes of finding audio material, but it was not to be. Lost and damaged elements are among the chief reasons. There was also never a second volume from FSM.

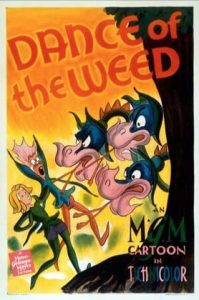

“There was a part of me that was hoping that we would put in earlier stuff if there could have been a volume two,” said Goldmark. “I knew it wasn’t going to happen because I know the elements probably didn’t exist. I knew realistically the material didn’t exist and also it was probably not in the cards. Dance of the Weed, for instance, all these ballet-driven scores. Especially that one because he specifically cited it numerous times.”

Dance of the Weed was an experiment between Bradley and Rudy Ising to create an animated film from an original composition from scratch. It was not unlike what Stalling and the other composers had done with Silly Symphonies, but according to Bradley’s mentioning of the film, this was something different and special. Looking at it now, it has a Fantasia/Make Mine Music/Silly Symphony feel to it, but a better understanding the effort makes it worth a great deal more attention, especially if Ising truly inverted the process for Bradley. Perhaps by 1941, the circumstances were not going to support such ideas.

Bradley believed animation music was one of the most important art forms of the twentieth century that would only offer more potential by the next millennium. “As to the future, I believe that this medium offers the serious composer far more possibilities than the live-action pictures. The animated fantasy of the future will, I hope, be adapted to pre-composed music. We have only to imagine a Debussy composing ‘The Afternoon of a Faun’ as the basis of such a picture, to visualize the importance of music in cartoons.” Who else was saying this in the 1940s?

“The question would be, is the pride in that he was trying to take what he did seriously? Goldmark wondered. “Was it that he was not just a composer of funny pictures, where he’s seen as just the guy writing for cat-and-mouse chases all the time, being typecast for it?”

So many answers lie somewhere in between, perhaps this one does as well. The most important thing is to do the best you can and try to enjoy the ride.

“Fun? Loads of it!” Scott Bradley wrote in of his score for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Mouse in a 1947 Music Educators Journal Essay, reprinted in The Cartoon Music Book. “I’d rather score a cartoon like this than a half-dozen ordinary live-action pictures. No noisy actors shouting at the top of their voices, drowning out perfectly good music!

“Deputy Droopy”

A full stereo soundtrack from a complete MGM cartoon is like Blu-ray for the ears.

GREG EHRBAR is a freelance writer/producer for television, advertising, books, theme parks and stage. Greg has worked on content for such studios as Disney, Warner and Universal, with some of Hollywood’s biggest stars. His numerous books include Mouse Tracks: The Story of Walt Disney Records (with Tim Hollis). Visit

GREG EHRBAR is a freelance writer/producer for television, advertising, books, theme parks and stage. Greg has worked on content for such studios as Disney, Warner and Universal, with some of Hollywood’s biggest stars. His numerous books include Mouse Tracks: The Story of Walt Disney Records (with Tim Hollis). Visit

“Milan used an illustration of Red and the Wolf, perhaps in hopes of finding audio material, but it was not to be.”

It feels very obvious that they used a motive of Red and Wolf (from Swing Shift Cinderella) simply because they are two of Avery’s most recognizable characters. If you wanna sell a CD with scores from Tex Avery films, design the cover so people notice it immediately. Promotional art of the Wolf and Red based on “Red Hot Riding Hood” was even used on the back cover of the 2007 Droopy DVD set.

It’s great that these audio recordings have been made from the cartoons’ original soundtracks. It would be even better if Bradley’s scores and orchestral parts could be made available to orchestras today, to be performed in concert and recorded with state-of-the-art technology. Unfortunately, as Dr. Goldmark says, this material probably no longer exists. It could conceivably be reconstructed: I have written arrangements of cartoon music cues (mostly by Stalling, but also by Japanese anime composers Masaki Kurihara and Satoru Kousaki) by transcribing them by ear from the soundtrack, using a lot of pause/play. But I wouldn’t have a prayer of transcribing something as complex as a Scott Bradley MGM score, and any musician talented enough to do so would probably have better things to do.

As “Dance of the Weed” makes clear, Bradley found the highest expression of the animated cartoon as a form of ballet: storytelling through characters in rhythmic motion, without dialogue. The score recalls the ballets of Stravinsky (especially “The Firebird”) and Ravel, and also the seductive waltz from Bartok’s only ballet, “The Miraculous Mandarin” (which also contains a lot of the yawning trombone glissandos that feature so prominently in Bradley’s cartoon scores). I’ve never read any comparison between Bradley’s music and that of George Gershwin, but the similarities are obvious. Bradley’s blending of jazz with modern music sounds very much like Gershwin’s concert works, especially “An American in Paris” (which, though not a ballet as such, has been adapted into one). Gershwin made his fortune composing musical comedies, which MGM cartoons are all about.

Dr. Goldmark’s mention of Bradley’s interest in Schoenberg brings to mind one of my complaints about his book “Toons for ‘Toons”. Much has been written about Bradley’s incorporation of Schoenberg’s twelve-tone system into his cartoon scores. In 1944 Bradley gave a lecture to an audience of film industry people in which he mentioned using a “twelve-tone scale” for a passage in “Puttin’ on the Dog”. “I hope Dr. Schoenberg will forgive me for using his system to produce funny music,” he joked. Four years later, John Winge wrote in an article that “For years Bradley has been using [the Twelve-Tone System] too, as probably the only composer in his field.” This has been repeated uncritically over the years.

Now, a “twelve-tone scale” is a way of describing the chromatic scale, with twelve pitches in every octave. Schoenbergian compositional technique, called serialism or dodecaphony, is built on the twelve-tone *row* (from German, die Reihe), in which the twelve pitches of the chromatic scale are arranged in a particular order that serves as the basis for a composition. Thus all tones are equal, and there is no tonal centre. The row can be stated in its prime form, or in its inversion, retrograde, or retrograde inversion forms; it can be transposed; it can be divided into constituent hexachords or tetrachords; but the entire row must be stated before it can be repeated. There’s a lot more to it, but the point is, Bradley never did any of that. A series of twelve chromatic pitches, eo ipso, is not the same thing as using Schoenberg’s system; you can find them in Bach and Handel. (I don’t even like twelve-tone music, but boy, did they ever hammer it into me in graduate school!)

Even worse, Goldmark has included the passage in question from “Puttin’ on the Dog”, also calling it a “twelve-tone scale” — but it’s obviously not a twelve-tone row, for the simple reason that there are sixteen notes in it!

The chapter on Scott Bradley contains some factual errors; for example, Goldmark states that Joe Barbera did the timing for the Tom and Jerry cartoons, when it was actually Bill Hanna. But what drives me crazy about “Toons for ‘Toons” is that practically every single one of the musical excerpts quoted in it are incorrect in some way. There are wrong notes, accidentals and bar lines in the wrong places, rhythms incorrectly transcribed, etc. The piano score to Raymond Scott’s “Powerhouse” has the left hand staff in treble clef, rather than bass. I know most books these days are badly edited, but there’s no excuse for this kind of sloppiness.

By the way, Schoenberg and Gershwin lived near each other in Los Angeles and were very good friends. They used to play tennis together.

Mr Groh, I am writing here as I could not reply to your other post further down.

I believe John Wilson’s “Tom and Jerry at MGM” orchestral piece was indeed transcribed by ear by Mr Wilson himself due to the original parts being lost. And yes, it is indeed a medley of excerpts from various Tom and Jerry cartoon scores.

When I first saw that video I was enthralled. I am a classical pianist and back then I (rather naively) emailed Mr Wilson asking if his orchestral arrangement was available for purchase as sheet music, and by extension, if there was a piano reduction available too!

He never wrote back, but I have long thought of attempting my own piano arrangement of Scott Bradley’s music. I am accustomed to playing by ear, but make no mistake I have never attempted anything as complex as Bradley! I am certain if I ever find the courage to try it I will have to use your play/pause method to decipher the rapid-fire cascade of notes in Bradley’s music. I might even have to use software to slow the music down! (without altering the pitch.)

Sorry that John Wilson never replied to your inquiry. I can pretty much guarantee that he never would have made a piano reduction of his Tom and Jerry arrangement! Best wishes for your efforts to arrange Bradley’s cartoon music for the piano, and I hope you have a lot of fun doing it!

Thanks Greg!

Music files were mentioned. Anyone know where TAJ&TAT can be downloaded?

Too bad Bradley’s 40s soundtracks can’t be unearthed. Extra brash ‘n’ brassy. Because, 1940s.

Wanna treat?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=seka_xO0UwI

Then why aren’t Bradley’s 1930s, 40s, and early 50s scores available sans dialogue and sound effects compared to his mid-late 50s work, which is available sans dialogue ans sound effects?

“they were cartoons for Avery, who he didn’t like composing for in the first place.”

More info, please. Thanks for this.

GDX — Thanks for including the BBC clip!

There are no music files for either CD. The Milan CD seems very accessible on Amazon right now, while the FSM, being a limited run, is more difficult to find and thus pricey. We can only hope for a reissue. Maybe HBO Max will start a streaming music service with a TCM/Boomerang brand, hmm? Maybe if we ask nice.

Hi Reg — Sorry if time did not permit further detail on the Bradley/Avery dynamic. It’s touched on further down after the quote as to interpolation and variance. You can even hear in the two Droopy soundtracks, which use virtually the same tunes, what Avery wanted from Bradley.

From what I gathered in my interview with Daniel Goldmark, Avery wanted the music to pay off the gags while Tom and Jerry and other MGM cartoons offered long stretches of neutrals, character scenes and continuous action as well as breakneck turns and stops. It does help if work with someone who appreciates what you bring or allows you more creative freedom.

Goldmark also said, “Avery’s about jokes. He’s a gag guy and he does it beautifully. If you’re looking for some nice long melodies, that ain’t gonna happen. For Bradley, that is not your media, you’re not going to get the chance to do that. I can see that being very frustrating for him.”

But this post was not intended to dwell on conflict. Animation Spin is more celebratory than “internetty” and “clicky.” However, it was historically important, to include a mention of a true and fascinating aspect.

Paul Groh : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kYrUWfLlYI0

That’s a terrific performance of Bradley’s Tom and Jerry music at the BBC Pops. The John Wilson Orchestra is a specialty orchestra, essentially a swing era-style Big Band with a full string section, specialising in vintage Hollywood film scores. (There are a lot of specialty orchestras nowadays, and Wilson’s definitely fills a niche.) In some cases, where the original orchestral score and parts no longer exist, Wilson and his team have painstakingly reconstructed them based on the soundtrack. I have no idea if they did this with Tom and Jerry. I also don’t know which cartoon the music comes from, or whether it might have been cobbled together from multiple cartoons; one of the YouTube commenters attributes it to “Cat Fishin'”, but that is clearly incorrect. In any case, it’s a wonderful arrangement, and I would love to be able to take part in a concert like that. However, it doesn’t look as though I ever will, because orchestras almost never hire out their in-house arrangements, especially if copyright is held by a third party. The John Wilson Orchestra can perform it to its heart’s content, but as soon as they start making money from it they’ll find themselves confronted by an army of entertainment industry attorneys. I hope they will arrange, perform and record more of Bradley’s MGM music; whether they ever do remains to be seen.

Didn’t Bradley write some concert pieces based on his scores?

Well, in 1938 Bradley composed a four-movement orchestral suite titled “Cartoonia”, which was premiered by the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Pierre Monteaux (who had conducted the premiere of Stravinsky’s ballet “The Rite of Spring” in 1913). Some sources say it’s based, at least to some extent, on his MGM cartoon scores; but, never having heard it, I can’t say for certain. Bradley’s other concert works, the symphonic poems “The Valley of the White Poppies” (1931) and “The Headless Horseman” (1932) and his oratorio “Thanatopsis” (1934) all predate his tenure at MGM. None of these works seems ever to have been recorded, and I have no idea where the scores and orchestral parts might be found.

I always thought it was a shame we never got a follow-up T&J & Tex Avery Too! volume, with more soundtracks from the mid to late ’40s, because IMO this was when Scott Bradley was at his best. But I understand, surviving elements and declining CD sales and all that.

I didn’t know he worked with a smaller ensemble than Warner Bros. did, but that would explain why his scores tend to have a thinner sound to them than Carl Stalling’s and, to a lesser extent, Milt Franklyn (I believe the latter also had a reduced orchestra around the early ’60s, right?). He still produced some great work, though.

And – even further reduced – Bill Lava!!

Lukas Kendall at FSM has mentioned some of the 40’s Bradley scores surviving in some form. I recall him mentioning the brief few bars of dance music from Mouse in Manhattan in particular. All may not be lost.

When exactly did he say this, and is there proof that he said it and proof the 40’s soundtracks are still around in some form?

Some years ago I found the first CD in a used bookstore. When the cute cashier rung up my purchase, she was momentarily excited until she saw it was a CD.

She knew Tex Avery and knew he was hard to find on DVD. If we were two or three decades closer in age I would have chatted her up.

Thank you fofr this informative post. Regarding Avery and Bradley not seeing eye to eye when it came to scoring for cartoons, well, my guess is that Avery chose the tune we hear in “WILD ‘N’ WOLFY”, as the girl comes to the stage and performs came from some long lost 78 that I am still trying to track down. I’d just love to hear this tune without the cartooniness surrounding it so I can hear all the lyrics. Then again, if this song was composed specifically for this cartoon, that search will no doubt be a bit harder for someone like myself who doesn’t get the chance to do the actual legwork to the cherished Warner Brothers or MGM vaults, and we all know that record-keeping at MGM was not as good as we would have liked it to be.

“DANCE OF THE WEED” is such a fine example of the magic that Braadley’s scoring and the Harman/Ising period of animation–that ability to neatly tell a story without a single sound from a human voice, save for Ising’s own growls as the “villain” of the story. While Hugh Harman was said to be disappointed that he never got to create his ultimate animated film, this particular cartoon might have been somewhat what he was a iming at. I recall seeing this in grainy black and white and being so captivated by it. I can only imagine what it looks like in color, and as always, I hope it does come to bluray as fully restored and shining, audiophonically, as much as it possibly can.

The other cartoon I marvel at is “DR. JEKYL AND MR. MOUSE” because it almost seems that the Bradley score and the sound effects are so neatly matched. I can’t imagine the scoring without that cadre of sound effects used for Jerry’s transformation into the threatening thing that advances on Tom as the cat throws everything he can at it; even the dated tone of the scores works on this one, and I wouldn’t toy with electronics on this one too much. At one late cartoon festival I attended, the theater had the sound turned up in the theater far too high, but when it came to the Bradley scores, I enjoyed the jarring volume on more than a few of the cartoons, despite the fact that said volume scared a little kid in the audience to crying. I know that, when I was that small, I didn’t like such high volume on movies I’d gone to see, but I appreciated the full tone of a bradley score. His use of Rossini’s pieces in “KITTY FOILED” is unique and, I’d dare say, more interesting than Carl Stalling’s use of the same piece in “RABBIT OF SEVILLE”, especially the nicely timed bit in which Tom ties Jerry to the tracks. Yes, it is funny and has gotten uproarious laughs at many a festival, but wow! Hearing it on a good sound system is just one of those unforgettable experiences…oh, and I’m happy someone else here brought up “MOUSE IN MANHATTAN”; is this another Bradley original? I’d always thought that this should have been the cartoon extra on the bluray of “ANCHOR’S AWAY”, even if the cartoon was not actually created at the same time as the live action film.

And, getting back to the extraordinary “DANCE OF THE WEED”, if the cartoon were included on a future CD of MGM cartoon scores, it really could exist on its own with an ever-so-slight bit of tweaking. There are only minimal sound effects and they don’t distract from the intensity of the scoring here, including the strings representing the wind whipping up and causing the flower ballerina to stumble into dangerous territory. Oh, I can go on and on and on about those classic toons and tunes. Thanks again for this great post.

This just occurred to me, but I wonder if the title “Dance of the Weed” was inspired by “Chant of the Weed”, a Prohibition-era “reefer song”. Don Redman and his orchestra play it over the opening credits of the Betty Boop cartoon “I Heard”.