And, as it happened unto a Cat, so did it happen unto a Mouse.

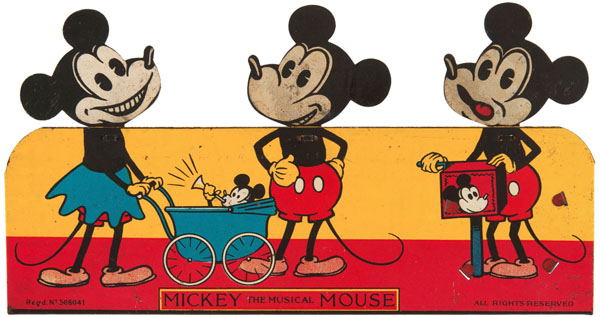

The story of the early days of Mickey Mouse is so well-known to cartoon buffs that I’ve no need to repeat it here. It’s possible that we can all recite it by heart.

What I can say is that, by the end of 1929, the Mickey Mouse cartoons were enormously popular, not only with the general public, but with high-falutin’ film critics, who liked the fact that these cartoons–unlike some of the features that they accompanied–actually MOVED, and with music, sound effects, and minimal dialogue, to boot!

What I can say is that, by the end of 1929, the Mickey Mouse cartoons were enormously popular, not only with the general public, but with high-falutin’ film critics, who liked the fact that these cartoons–unlike some of the features that they accompanied–actually MOVED, and with music, sound effects, and minimal dialogue, to boot!

You would think that Tin Pan Alley would be stumbling all over itself to cash in on the newest fad. Not so fast, there!

It wasn’t in Tin Pan Alley that the first successful “Mickey Mouse” song came into being–but, again, it was on Denmark Street.

Ideal Films had the shorts for Great Britain (and, presumably, for Ireland, as well). They must have been widely popular–perhaps as popular with UK audiences as with us Yanks. (British audiences preferred American pictures anyway–which is what led to the quota laws passed in 1927, mandating that producers and theaters show a certain quota of British films–which led to several different phenomena, which are outside the scope of this here column.)

Harry Carlton had been writing songs ever since the early ‘Teens. Much of his work was in the repertoire of various singers and entertainers of the Music Hall, or its successor, Variety. One of his best customers early on was Billy Williams, an Australian given over to a velvet suit, and a gasping intake of air–who was even known here through the medium of phonograph records.

In 1928, Carlton had a surprising international hit with “C-O-N-S-T-A-N-T-I-N-O-P-L-E”, a “spelling” song, which was not only a hit in the UK, but also in the USA, where it was covered by several prominent singers and bands–the most prominent of which was Paul Whiteman, who has been discussed before in this column.

One would like to think that Carlton might have been a movie goer himself–watching imported American talkies, and those early British talkie features that were just hitting the screens then–films like Blackmail (with Alfred Hitchcock directing a cast headed by Anny Ondra). And, seeing how the audience reacted to an early “Mickey Mouse” short, one would picture him retiring to his study, and coming up with a song about the animated character.

The song was widely covered by almost all the UK record companies of late 1929 and early 1930. Among the most prominent are the Columbia record by Debroy Somers’ Band, and the lowre-priiced Zonophone record credited to “The Rhythmic Eight”, directed by John Firman.

Barring further research, we don’t know how the cartoons did when they played in German. But the song–there called “Micky Maus“, and fitted with a German text–was widely covered by nearly all the German firms of the day. Some of the top bands of Berlin recorded the song, with most versions following a “stock” arrangement of the piece.

We don’t know if the “Mickey Mouse” cartoons continued to run in Germany once Herr Hitler came to power. But, for the German man in the street, it was fun while it lasted.

Next in this series: More Mickey Mouse

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

I remember a book, Disney Dons Dogtags, they shown a WWII Nazi military Insignia showing a “bootleg” Mickey Mouse in some sort of sphere type of armor and carrying a Blunderbuß (Blunderbuss) pistol in one hand, A hatchet in another hand and showing Mickey smoking a cigar.

According to several news reports and sources Adolf Hitler was a huge fan of Waly Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs – and that he did sketches of the Dwarfs, Bashful and Doc, with the initials A.H. marked on them – along with a unsigned sketch of Pinocchio that he did. They also said that the “A.H.” Initials were also found on official documents that he signed.

Oh, wow! Great stuff!