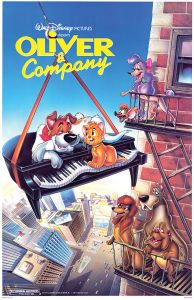

In Jerry Beck’s book, The Animated Movie Guide, contributor Martin Goodman called Disney’s Oliver & Company “… an entertaining movie that represented the studio’s final dress rehearsal for the great successes of the 1990s.”

In Jerry Beck’s book, The Animated Movie Guide, contributor Martin Goodman called Disney’s Oliver & Company “… an entertaining movie that represented the studio’s final dress rehearsal for the great successes of the 1990s.”

Coming to theaters just one year before The Little Mermaid (the film that kicked off the Renaissance era), Oliver & Company was indeed an excellent “warm-up lap” for the artistic leaps and box-office blowouts on the horizon for Disney.

In 1984, Roy E. Disney, Walt’s nephew, disagreed with the company’s direction and resigned his seat on Disney’s Board of Directors. Roy was then instrumental in bringing aboard a new leadership team at Disney, including Frank Wells as President and Michael Eisner as Chief Executive Officer.

Part of this incoming team’s vision for Disney was to ramp up the production of animated features. Ideas for future films would come from pitch meetings dubbed “The Gong Show.”

The name and inspiration for these meetings came from a popular ‘70s TV talent show, where amateur acts would perform for celebrity guest judges, who would sound a gong for those they didn’t like.

It was in one of these meetings that Pete Young, a story artist with the Studio, pitched an idea: “Oliver Twist with Dogs,” a re-telling of Charles Dickens’ literary masterpiece, but this time, a kitten would be befriended by a cast of canines. The film was given the green light under the original title, Oliver & Dodger.

Set in contemporary 1980s New York City, the film centered on Oliver, a cute kitten left alone on the streets, who is befriended by the mutt Dodger and a ragtag gang of fellow strays, whose owner is Fagin, a sad-looking pickpocket.

Set in contemporary 1980s New York City, the film centered on Oliver, a cute kitten left alone on the streets, who is befriended by the mutt Dodger and a ragtag gang of fellow strays, whose owner is Fagin, a sad-looking pickpocket.

Fagin works for Sykes, an imposing mobster-like villain, who travels in a sinister-looking car with his two sidekick Dobermans.

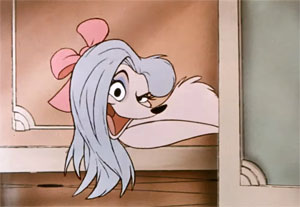

Oliver is separated from Dodger and the gang and adopted by a kind-hearted young wealthy girl named Jenny, who lives in a luxurious apartment with her spoiled poodle, Georgette.

Dodger and the gang bring Oliver back from Jenny’s to Fagin, who decides to hold Oliver for ransom to help pay back a debt he owes to Sykes, who gets involved and winds up kidnapping Jenny. Fagin, Oliver, and the dogs try to rescue Jenny, resulting in a car chase scene that culminates on the elevated tracks of the subway.

The sequence is gripping and well-choreographed, incorporating computer-generated animation, which would continue to play a larger role in subsequent features. Just before Oliver & Company’s release, the film’s director, George Scribner, told writer John Culhane for a New York Times article that computers “do the inanimate objects, freeing the animators to spend more time on the flesh-and-blood creations. And because New York City itself is in some respects another character in the picture, we wanted it to be realistic, not just static backgrounds. We wanted lots of movement and traffic.”

The sequence is gripping and well-choreographed, incorporating computer-generated animation, which would continue to play a larger role in subsequent features. Just before Oliver & Company’s release, the film’s director, George Scribner, told writer John Culhane for a New York Times article that computers “do the inanimate objects, freeing the animators to spend more time on the flesh-and-blood creations. And because New York City itself is in some respects another character in the picture, we wanted it to be realistic, not just static backgrounds. We wanted lots of movement and traffic.”

The scene’s finale feels like a sequence out of an 80s action movie and is one of the film’s grittier elements that differentiated Oliver & Company from previous Disney animated features. In their book, The Disney Villain, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston discuss how even Sykes was initially supposed to be a shadowy and more ambiguous villain: “The story development called for more and more action for Sykes, however, and the concept of keeping him in the shadows had to be abandoned.“

Critics noted the film’s tone, such as New York Daily News’ Kathleen Carroll, who called Oliver & Company a “Grim Disney Tale” in the headline for her review and stated that the film “…adopts the same dark, sinister view of the world as Who Framed Roger Rabbit.”

An element that was more familiar in the film was its use of well-known voices in the cast, including Billy Joel as Dodger, Bette Midler (who was the star of several popular live-action films for Disney’s Touchstone Pictures) as Georgette, Cheech Marin as Tito, Dom DeLuise as Fagin, Sheryl Lee Ralph as Rita, Roscoe Lee Browne as Francis, Richard Mulligan as Einstein, (then) child star Joey Lawrence as Oliver, and Robert Loggia as Sykes.

An element that was more familiar in the film was its use of well-known voices in the cast, including Billy Joel as Dodger, Bette Midler (who was the star of several popular live-action films for Disney’s Touchstone Pictures) as Georgette, Cheech Marin as Tito, Dom DeLuise as Fagin, Sheryl Lee Ralph as Rita, Roscoe Lee Browne as Francis, Richard Mulligan as Einstein, (then) child star Joey Lawrence as Oliver, and Robert Loggia as Sykes.

Oliver & Company was also a musical (something that would continue through the animation renaissance era). Many of the songs in the film would be performed by a Top 40 pop artist, such as Huey Lewis singing “Once Upon a Time in New York City,” Billy Joel as Dodger singing the showstopper “Why Should I Worry?,” Rita’s song “Streets of Gold” was performed by Ruth Pointer of the Pointer Sisters, and Bette Midler as Georgette performed the glorious “Perfect Isn’t Easy,” with lyrics co-written by Midler’s former collaborator, singer Barry Manilow.

Oliver & Company debuted on November 18, 1988 (Mickey Mouse’s 60th birthday), and in an ironic twist, it opened the same day as The Land Before Time, which was directed by Don Bluth, who had led a walkout of animators from Disney in 1979, which garnered a lot of attention. Bluth had also directed 1986’s An American Tail, which was, at the time, the most successful non-Disney animated feature.

Oliver & Company debuted on November 18, 1988 (Mickey Mouse’s 60th birthday), and in an ironic twist, it opened the same day as The Land Before Time, which was directed by Don Bluth, who had led a walkout of animators from Disney in 1979, which garnered a lot of attention. Bluth had also directed 1986’s An American Tail, which was, at the time, the most successful non-Disney animated feature.

The two animated films opening on the same day was a “Barbenheimer”-like movie occurrence of another time (for more on The Land Before Time, see last month’s “Cartoon Research” article.

Both films were successful, with Oliver & Company taking in $53 million at the domestic box office.

Looking back at the film thirty-five years later, Oliver & Company showed how a generation of Disney artists, trained, and mentored by the generation of artists who worked with Walt himself could craft a compelling, entertaining film with well-developed characters and a distinct voice.

This was noted on Oliver & Company’s first day in theaters by New York Newsday film critic Lynn Darling, who wrote: “Happily, Oliver & Company is a contemporary cartoon that pulls off a tricky balancing act. It can take an occasionally sly eye to the crazy city in which it’s set without losing sight of the innocence at the core of the movie’s charm.”

Michael Lyons is a freelance writer, specializing in film, television, and pop culture. He is the author of the book, Drawn to Greatness: Disney’s Animation Renaissance, which chronicles the amazing growth at the Disney animation studio in the 1990s. In addition to Animation Scoop and Cartoon Research, he has contributed to Remind Magazine, Cinefantastique, Animation World Network and Disney Magazine. He also writes a blog, Screen Saver: A Retro Review of TV Shows and Movies of Yesteryear and his interviews with a number of animation legends have been featured in several volumes of the books, Walt’s People. You can visit Michael’s web site Words From Lyons at:

Michael Lyons is a freelance writer, specializing in film, television, and pop culture. He is the author of the book, Drawn to Greatness: Disney’s Animation Renaissance, which chronicles the amazing growth at the Disney animation studio in the 1990s. In addition to Animation Scoop and Cartoon Research, he has contributed to Remind Magazine, Cinefantastique, Animation World Network and Disney Magazine. He also writes a blog, Screen Saver: A Retro Review of TV Shows and Movies of Yesteryear and his interviews with a number of animation legends have been featured in several volumes of the books, Walt’s People. You can visit Michael’s web site Words From Lyons at:

It’s far from perfect, but it is certainly superior to the 80’s Hanna Barbera style The Great Mouse Detective.

The static frozen backgrounds of Times Square resemble the worst seen in Orville’s city flight in The Rescuers.

The voice talent is all over the place. Dom De Luise is miscast and Billy Joel proves why he chose singing over acting.

But while I have never been a fan of Bette MIdler or her offscreen antics, her performance is a delight. Ditto Cheech Marin.

It was probably not the best story to adapt – Oliver (1968) and Oliver Twist (1948) are far superior retellings.

The director George Scribner appears to have only directed one more project (apart from a Disney park attraction).

Another classic book adaption – The Prince And The Pauper (1990) – again inferior to the live action Disney version (1962).

(He probably wished he was still working on The Biskitts or Challenge Of The Gobots)

.

“The Great Mouse Detective” as H-B style? Seriously? I thought that was quite well-done. And besides, if it weren’t for that film, Disney would’ve stop doing animated feature films.

Also, I thought “The Prince and the Pauper” was also a nice little featurette with Mickey. And that last quirk on the director was rather uncalled for.

I think there is a strong case to be made that, whatever one thinks of the film, it, rather than The Little Mermaid, was the true start of the Disney Renaissance. It began their cycle of yearly films and at the time it left theatres had the unadjusted highest gross for an animated film from a single release.

I absolutely agree! I tend to lump Oliver and The Great Mouse Detective with the Renaissance. Both films signaled the upturn of Disney Animation’s fortunes, and both did a great job of featuring the talents of Disney’s new crop of animators.

I still remember seeing Oliver and Company in the theater when I was five years old. I still remember seeing Georgette dancing down the staircase, it still sticks in my mind.

Oliver and Company also represents the last theatrical use of the Xerox technique which had informed every Disney animated feature film and short subject since “One Hundred and One Dalmatians”. While efficient and effective, this method had given a sort of “generic Disney” look to all of the features that made use of it. It definitely branded these features as Disney productions, but to my eyes at least there was a sort of sameness about it. Thus when “The Little Mermaid” debuted a year or so later, the return not only to fairy tales. but to a more solid form of line drawing, appeared at once as both a throwback to the animation of the 40s and 50s but also as a harbinger of new directions to come.

The Xerox technique was brought back at least once that I have noticed in the sequel to “One Hundred and One Dalmatians”–the direct-to-video release of “Patch’s London Adventure”–a clever nod to the then-innovative look it had given to the original.

Little Mermaid also had the Xerox technique, it was only the wedding sequence which had CAPS

Oliver was the last film to use Xerox lines on the backgrounds, which was first used on One Hundred and One Dalmatians as a way to match the Xerox lines on the character cels.. It was used on every Disney film afterwards until The Rescuers, except for Jungle Book, after which they switched back to full tonal backgrounds. The Xerox background look was revived for the 2011 Winnie the Pooh film (all Pooh media use the style as an homage to the original Ernest H. Shepherd illustrations) and was also used on some TV and direct-to-video productions.

The difference wasn’t in the use of xerox, it was in the way the clean up artists were asked to do the final artwork. The “xerox” style of the 60s and 70s was an attempt to retain the vitality of the animators’ original drawings, (which was made possible by the xerox machine,) so the follow-up artists who did the breakdowns and in-betweens mimicked the line quality of the animators’ key drawings. For The Little Mermaid they wanted to hearken back to the⁰ ink-lined final artwork of the early features, so a hard clean line was put on the animators’ key drawings and the follow-up artists followed suit. If my memory serves correctly, we even used mechanical pencils to do the final artwork, since they encouraged a cleaner thinner line that looked more like an ink line. They were still xeroxed, though.

Always thought the animation and character design in this one was all over the map–Sometimes its fine, other times it looks like Filmation with a bigger budget. Fagin seems to have came straight from a Ralph Bakshi production.

Like the article said, this was a decent warm-up for what was to come in studio’s Renaissance era. Although the staff latter joke that they learned (according to a Disney Twenty-Three article written by our own Greg Ehrbar) how NOT to do an animate musical, there was another hint to what’s to come as the opening song “Once Upon a Time in New York” was the first song written by Ashman for a Disney film.

I think “Oliver & Company” ushered in the Busby Berkeley-style musical numbers that became standard in the Disney animated features for the next several years.

I enjoyed this movie when it came out and reviewed it for Animato. I also interviewed George Scribner–a great guy who I’d known for some years at that point because his parents were neighbors of my grandmother. Here’s the Animato coverage: https://archive.org/details/animato_201912/Animato%2018/page/20/mode/2up

Thanks for sharing, Harry! I loved “Animato!” and was fortunate enough to write several articles for the magazine back in the 90s.

I swear I have never heard of this before. Better put this on the watchlist!

I guess it was the warm-up for The Lion King, being it’s a jungle version of Hamlet.

When this finally hit VHS in the UK in 1997, I was 10 and had never heard of it. I was already a pretty big Animation/Disney History buff, but because this was pre-internet (at least for me) I was relying for knowledge on books like The Disney Studio Story by Richard Hollis and Brian Sibley, which ended in 1986, so it was a real treat to have a unknown “proper” Disney animated film suddenly come into view. I was a little disappointed when I finally watched it, but that doesn’t really matter. I don’t think a 10 year old with similar passions could be surprised in the same way in the internet era.

I will never not be upset how this very loose adaptation of Oliver Twist missed the point of Oliver Twist HARD.

A friend and I skipped school to catch a matinee of this movie when it came out.Of course we had a unexcused absence to account for the next day and we both got dention.When our folks found out.His folks barley blinked.My dad went balistic on me.It was worth though.

Did this get a theatrical reissue before Disney discontinued them? I remember “Great Mouse Detective” was reissued in 1992 (screening in tandem with ‘Beauty and the Beast’ at one point) in conjunction with its debut on VHS, and “Oliver and Company” should logically have been the next in line some time in the late 1990s. I don’t remember ever hearing of one, but one year the summer reading program I volunteered for had giveaways of what (I thought) looked like a reissue theatrical poster for this film.

Maybe it was just for the VHS release?

At least in the US it got a re-release in early 1996, about a year before its first VHS release. It grossed $20million, not bad all things considered. It was released the same day as All Dogs Go to Heaven 2, almost certainly not a coincidence, and beat it handily.

The Little Mermaid also got a theatrical re-release, I guess their last “conventional” re-release; Beauty & the Beast and The Lion King were re-released twice each, but these were limited and/or special event re-releases, fist in IMAX in the early-00s, and later in 3D in the early-10s.

Yep, 1996 lines up with what I remember. Thank you for confirming that! In all honesty I might have gotten a bigger kick out of seeing ‘Oliver & Company’ on the big screen that year rather than ‘Hunchback of Notre Dame’!