Continuing my research on the marketing of animated cartoons in the 1930s by examining the Loew’s theater chain in New York City. (Part 1 of this report can be read here). What follows are my thoughts on each of the cartoon studios, in order, by amount of cartoons shown in Loew’s theaters during the 1930s.

A. Disney

As is well known, Disney was the market leader in American animation during the 1930s, with dominance shown in its haul of Academy Award nominations and wins, as well as the substantial revenues generated by merchandising, books and comic strips. It does not strike me, therefore, as surprising that Disney would be so prevalent in the listings for the Loews New York theaters, as a clear number one.

As is well known, Disney was the market leader in American animation during the 1930s, with dominance shown in its haul of Academy Award nominations and wins, as well as the substantial revenues generated by merchandising, books and comic strips. It does not strike me, therefore, as surprising that Disney would be so prevalent in the listings for the Loews New York theaters, as a clear number one.

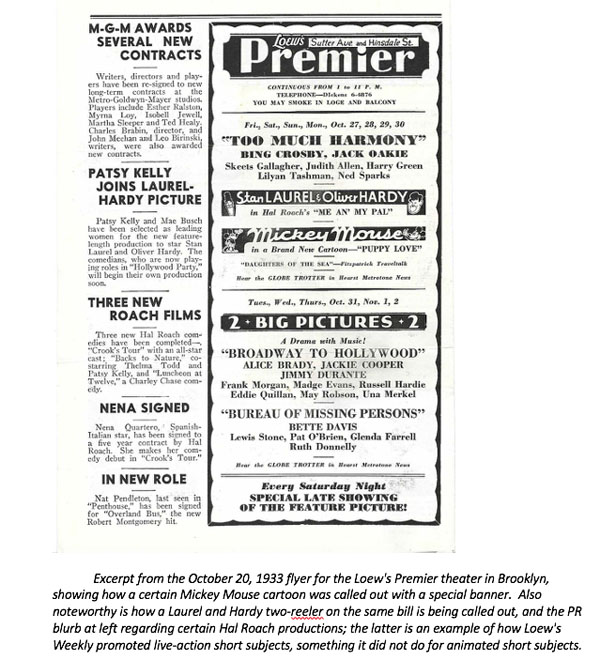

Moreover, unlike the offers from other studios (even MGM’s own cartoons), there were repeated instances where either a Mickey Mouse cartoon or a Silly Symphony cartoon would be called out with a mini-banner headline, as a Mickey Mouse cartoon or a “special added attraction.” The special banners appear to have been used only during two seasons, 1933-1934, and 1934-1935; at least the first of these seasons is a season where United Artists seems to have had a special arrangement with Loew’s in New York City. This does suggest at least some marketing muscle by United Artists with respect to a popular product.

The bulk of the 92 Disney cartoon showings came during the period when Disney cartoons were distributed by United Artists. Numerically, the Disney cartoons show on a “same bill” 16 times, or just over 17% of the total number of Disney cartoon appearances. I was slightly surprised by this number, which is a little below the average for the sample, and it suggests that while United Artists had some leverage with the Disney cartoons to get United Artists’ product into Loew’s theaters, they did not have consistent success.

No RKO-distributed Disney shorts show up in the sample; the last Disney cartoon identified in the sample is “Mickey’s Amateurs,” which was distributed by United Artists and shown at the Loew’s Premier in April of 1938 (over a year after its April, 1937 release).

I believe that in this instance, the drawing power of the Disney cartoons may have had at least some positive effect on United Artists’ ability to place cartoons in the Loew’s New York City theaters; it would be interesting to speculate how United Artists would have done without the Disney cartoons. Similarly, the lack of RKO-distributed shorts in the post-1937 era might indicate that RKO was keeping the cartoons for itself, or using them as bargaining chips in New York City with other chains in the area; the absence of the cartoons after a striking period of dominance is telling. One would need access to a supply of RKO Newsettes for the New York City era in the post-1938 period to analyze this.

B. Fleischer

Popeye can be fairly said to be Mickey Mouse’s greatest challenger for popularity among American animated cartoon characters of the 1930s, and his 34 appearances in the sample, second only to Mickey Mouse (on a character level), would appear to support this position, even accounting for some duplicate showings. The earlier and overlapping Talkartoon and Betty Boop series also do quite well, with 29 appearances. In fact, on a combined basis, Disney and Fleischer represented a majority of all of the cartoon listings in the survey.

Popeye can be fairly said to be Mickey Mouse’s greatest challenger for popularity among American animated cartoon characters of the 1930s, and his 34 appearances in the sample, second only to Mickey Mouse (on a character level), would appear to support this position, even accounting for some duplicate showings. The earlier and overlapping Talkartoon and Betty Boop series also do quite well, with 29 appearances. In fact, on a combined basis, Disney and Fleischer represented a majority of all of the cartoon listings in the survey.

The Color Classics do not fare particularly well, only four instances showing up in the sample. One of the three two-reel Popeye shorts, Popeye the Sailor Meets Sinbad the Sailor, does show up in the sample (and is included among the Popeye shorts — the Weekly referred to it in the listings as a “featurette in color”). Lastly, one of the “Stone Age” cartoons does appear at the very end of the sample period.

There were 23 instances where a Paramount cartoon shows up on a bill with a Paramount feature, more than any other studio, and at one-third of cartoon showings, well above average and tied for the most on a percentage basis. The listings also suggest that Paramount had a great deal of success overall in placing its features in Loew’s theaters. While not direct evidence of linkage, the prevalence of both features and cartoon shorts is quite striking.

The totals above do not include the showing of the Fleischer feature Gulliver’s Travels, as that was a feature. I do not see any evidence that Disney’s Snow White played in any Loew’s theaters in New York City in early 1938, though the sample is relatively small. Of course, the RKO theaters were showing it.

Given that Loew’s and Paramount had a direct relationship in the construction and leasing of certain theaters, including some major theaters in Brooklyn, it is perhaps not surprising that Paramount was able to place its cartoons successfully in the Loew’s theaters.

C. Mintz

For purposes of this analysis, I have assigned all of the Columbia cartoons outside of the Disney cartoons to the Mintz studio, though Mintz sold his operations to Columbia in 1939.

Given the relatively modest reputation of the Mintz studio’s output of the 1930s, it is rather surprising to see so many appearances in the sample; the 43 appearances are the third-most of any cartoon studio by a fair margin, with Krazy Kat and Scrappy making numerous appearances, and the Color Rhapsodies doing far better than its rival Fleischer Color Classics.

The record of Columbia is intriguing, because in some cases, there is very clear success; aside from the large number of Columbia cartoons placed, the raw data in the survey shows that Columbia was able to place a great number of features in the Loew’s theaters. Intriguingly, there’s little evidence of one of Columbia’s most successful products of the 1930s, the Three Stooges live-action shorts; only three instances in the survey were found where they showed up on a bill (none with a Columbia feature).

Based on the facts that Columbia was able to place its features and cartoons regularly throughout the period of the survey, but rarely on the same bill, suggests to me that Columbia had success in block-booking its cartoons with its features, but did not necessarily force them to appear on the same bill, unlike what Warner Bros. appears to have done (see below).

D. Harman-Ising MGM

The “Happy Harmonies” series, which was a direct competitor to the Disney “Silly Symphonies” series, fares fairly well in the survey, especially when one considers that only for a few years (late 1934-early 1938) would these cartoons have been released to theaters. The 28 appearances by the Happy Harmonies cartoons (including a few multiple appearances) places the Harman-Ising studio in a solid fourth, and not far behind some other series individual series like Popeye, Silly Symphonies, or the Talkartoon/Betty Boop series. 22 of the 37 Happy Harmonies cartoons produced appear in the sample, and the relative weakness of 1937 and 1938 programs in the sample might understate, slightly, the prevalence of the series in Loew’s New York City theaters.

9 of the 28 appearances were on the same bill as an MGM feature, the second-highest percentage (roughly 32%) of any studio and numerically the third most of any studio in the survey. This does suggest that MGM, on a significant basis, chose to package the Harman-Ising cartoons with its feature product.

One item of interest is that none of the Loew’s Weekly issues carries any promotional material for the Harman-Ising cartoons (or, for that matter, for the earlier Iwerks series); MGM did not neglect its short subjects in the Weekly, making repeated references to its live-action Pete Smith and Our Gang shorts (the latter produced in cooperation with Hal Roach). Nor were any of the Harman-Ising cartoons called out with special banners, in the way some of the Disney Silly Symphonies were.

The survey results do, however, suggest that MGM may have had slightly more confidence in Harman and Ising’s output than it did in Ub Iwerks’ output.

E. Iwerks

E. Iwerks

Of the 19 Iwerks cartoons that were identified in the survey, four of them were from the Comi-Color series distributed by Celebrity Pictures, after Iwerks’ ties with MGM were severed in 1934. Interestingly, three of the four appearances were during the 11 AM Saturday showings described above.

The fifteen appearances of Iwerks cartoons during his MGM era (seven Flip the Frog, eight Willie Whopper) are a somewhat surprisingly small showing. On the other hand, 5 of the 15 appearances were on the same bill as an MGM cartoon. This does give the Iwerks/MGM output a tie for the highest “same bill” percentage of any studio, at 33%, though on a smaller basis than the Paramount shorts.

Half of the Willie Whopper cartoons produced were found in the sample, but only a small fraction of the Flip the Frog cartoons, especially when one considers that during that series’ production run, cartoons from many other studios were shown. Given the relatively small number of samples from late 1930 through 1934, this might affect the Iwerks studio’s numbers.

It might be surmised that this showing is an indication that the MGM studio may not have had a great deal of confidence in the Iwerks output, a surmise that is possible when one considers the relatively stronger showing of the Harman-Ising cartoons, discussed above. Of course, the fact that when it did appear, it was packaged with MGM product, is notable.

As noted above, the Loew’s Weekly does not contain any sort of promotional material for the Iwerks studio. MGM did promote the series in advertisements in other industry publications, to be sure, but it is curious that the series did not fare better in the Loew’s Weekly sample.

F. Terrytoons

Prior to 1937, the Terrytoons output was distributed by Educational Pictures, which in turn was backed by Fox Film Corporation (after 1935, 20th Century Fox). However, all nine of the Terrytoons identified in the sample come in the 1930-1933 period, when the cartoons were distributed by Educational.

It does not appear, judging from the listings, that Fox placed many of its feature films in the Loew’s New York City theaters; for that matter, the famous Fox Movietone newsreel was not seen in the listings, in favor of the competing offers from Hearst/Metrotone (MGM’s own newsreel) or Universal’s newsreel. Fox did have some noteworthy theaters in the Brooklyn area, which might affect the sample, though not the kind of chain that Loew’s had.

The lack of strength by Fox in the Loew’s theaters is potentially a significant factor in the relatively poor showing by Terrytoons; another, more obvious one might be tied to the reputation the Terry studio had for low-budget offerings and a style that by the mid-1930s was archaic. The Terry studio had been hotly competitive in the silent era, but by reputation it had fallen well back in the pack by the early 1930s.

It is also possible that the failed takeover of Loew’s by Fox Film Corporation in 1929-1930 may have soured relations between the two studios, which would have had an effect on Fox placing its output in the Loew’s New York City theaters, at least in the early part of the sample period.

G. Schlesinger

G. Schlesinger

Somewhat analogous to the situation involving Terrytoons is the situation involving Leon Schlesinger’s studio, which produced cartoons for Warner Bros. (through Harman and Ising up to mid-1933, and then directly from Schlesinger after, up to mid-1944).

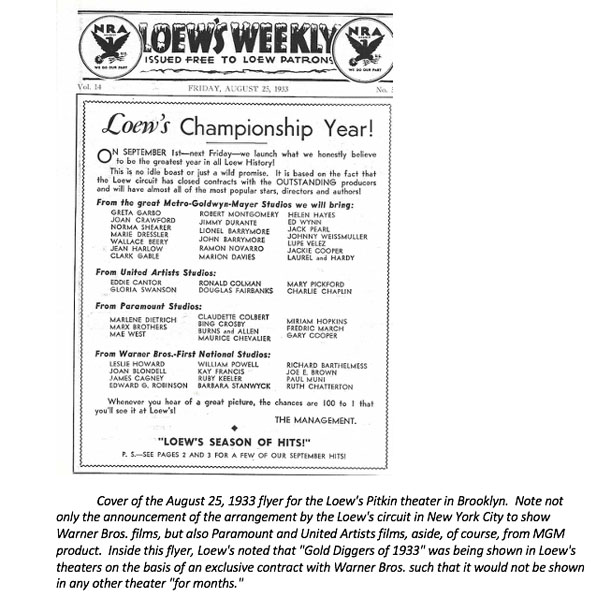

Warner Bros. did have ties to the Loew’s theater chain; indeed, issues of the Weekly in 1933 made much of the fact that, for example, Gold Diggers of 1933 (a major WB production) was going to be shown exclusively in the New York City area in the Loew’s theaters. In boasting of an upcoming “championship year,” Loew’s made much of the fact that a number of Warner Bros.-First National stars were going to be appearing in pictures to be shown by Loew’s.

However, while the survey shows that Warner Bros. was very successful in placing features in the Loew’s New York City chain up through mid-1935, its success after the 1934-1935 season appears to have been non-existent.

It is noteworthy that 7 of the 22 appearances by Schlesinger cartoons occur when a Warner Bros. feature was also on the bill, the third-highest result in the survey by percentage, and 19 of the 22 appearances are concentrated in during the 1933-1934 and 1934-1935 seasons, when Warner Bros. was very successful in placing its feature films in Loew’s New York City theaters. No Schlesinger cartoon appears in the sample after 1935.

In addition, all nine of the Looney Tunes in the sample are from the much-maligned “Buddy” series, which lasted only during the two seasons that Warner Bros. was placing features in the Loew’s theaters, suggesting the use of some marketing muscle by Warner Bros. during that period for a weak product.

At some level, it is apparent Warner Bros was tying its cartoons fairly closely to its feature film packages, at least with regard to its relations with Loew’s in New York City. When the features did well, the cartoons did well; when they did not, neither did the cartoons.

The 15 appearances by Lantz cartoons, 12 of which were from the Oswald series, have a significant concentration in the 1930-1932 range, with eight of the 15 occurring in that period. In fact, the first cartoon identified in the sample, from March, 1930, is one of the Oswald cartoons, and not, say, a Mickey Mouse cartoon. 2 of these 15 appearances were on a bill with a Universal feature, which is near the bottom of the percentages for the studios.

Judging from the listings, Universal had a modest amount of success in placing its features in the Loews’ New York City theaters in the later part of the 1930s (certainly better than Fox or Warners), but it does not appear have been a regular thing, and its lack of strength vis-a-vis Loew’s seems to have spilled over to the Lantz offerings, which appeared only sporadically.

I. MGM (post Harman-Ising)

I. MGM (post Harman-Ising)

After the Harman-Ising studio’s contract with MGM ended, MGM went through a period of turmoil in its cartoon operations, as evidenced by a rapid turnover in management and creative personnel (e.g., Harry Hershfeld, Milt Gross, Friz Freleng). This period came toward the end of the period represented by the sample, and it is thus not surprising to me that only two cartoons, both from the “Captain and the Kids” series (and both of which happen to be the two color entries, Petunia Natural Park and The Captain’s Christmas) show up in the survey. Neither was tied to an MGM feature, and as with the Iwerks and Harman-Ising period, Loew’s Weekly does not promote the cartoon studio during this period.

Puss Gets the Boot, the first of the Tom and Jerry cartoons, was only released in February of 1940, nearly at the very end of the survey period; the second cartoon (The Midnight Snack) was not released until July of 1941, approximately a year after the Weekly seems to have ceased publication. The odds of this series, whose success made MGM a major player in animation, appearing in the survey is thus rather slim.

J. Van Beuren

J. Van Beuren

Only two identifiable van Beuren cartoons, an August, 1930 offering of the Fable Jungle Jazz and an April, 1932 offering of the Fable Toy Time, was found in the survey. None of the later Rainbow Parade cartoons appear, nor do any of the “Tom and Jerry” or “Cubby Bear” cartoons appear. Neither were tied to any RKO features.

Two key and related factors to the lack of van Beuren cartoons are the facts that RKO (the studio that released the van Beuren cartoons) was a major player in New York City theaters, and that RKO placed very few of its features in the Loew’s New York City theaters, based on a review of the features in the sample. Whatever one might say about the relative quality of the van Beuren output, these two factors, which are directly tied to the issue of block-booking, may have had a significant effect on the marketability of the van Beuren cartoons in Loew’s New York City theaters, and perhaps beyond the Loew’s chain. I do not have access to a sufficient number of RKO Newsettes to make any firm judgments regarding how RKO presented van Beuren product in its own theaters.

K. Mayfair (United Artists)

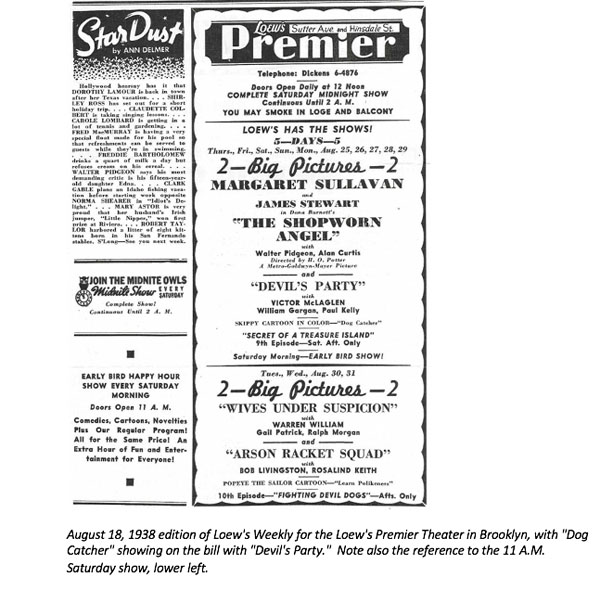

Lastly, there is one curio that turned up in the survey. When United Artists lost the rights to distribute the Disney cartoons, it sought to replace that studio’s output with fresh material. To this end, it contracted with a new studio, Mayfair Productions, to produce a series of cartoons based on Percy Crosby’s comic strip “Skippy.” Either nine or eighteen cartoons in the series were projected (accounts differ), but in the event, only one cartoon was actually completed at or prior to the time Mayfair Productions went bankrupt in early 1938. The completed cartoon The Dog Catcher, was copyrighted in May of 1938, and in late August of 1938, the Loew’s Premier theater in Brooklyn put it on a bill with The Shopworn Angel and Devil’s Party.

While Jerry Beck has stated that the Library of Congress retains a print of the cartoon, it does not appear to be in much, if any, circulation, and the appearance by the cartoon in the sample surely represents one of the few documented times the cartoon can said to have been publicly shown when it was new.

Frames from the rare print of Mayfair’s “Skippy” cartoon held at the Library of Congress

V. Conclusions

Based on my analysis of the evidence of the Loew’s Weekly sample of 1930-1940 New York City flyers, I think there is some evidence that certain of the Hollywood studios were using cartoons as part of a package supplied to Loew’s.

If a cartoon studio had success in placing its features, as Warner Bros. did in the 1933-1935 period, or Paramount did during the whole period, or Columbia seems to have done during the whole period, then that studio’s affiliated cartoons seem to have done well, though Columbia does not seem to have tied its cartoons tightly to its features, or at least not as tightly as Warner Bros. and Paramount seem to have done.

In the case of United Artists, the pulling power of the Disney cartoons, as evidenced by the special billing they got, might have been a significant factor in that studio’s relative success (for a minor studio) in placing films in Loew’s New York City theaters during the period they distributed the Disney cartoons.

Where studios did poorly in placing their feature films in the Loew’s theaters in New York City, such as Fox during the entire survey period, RKO during the entire survey period, or Warner Bros. after 1935, the associated cartoon offerings seem to have done poorly as well. Universal’s scattershot record of success, while better than these studios’, is of the same ilk.

For its part, MGM regularly used its own offerings in its own theaters, and regularly put them (at least during the Iwerks and Harman-Ising tenures) on the same bill as an MGM feature, but it does not appear that they favored their own product to the exclusion of other cartoon studios’ product; indeed, it could be argued (given the lack of promotion in the Weekly) that they may have underplayed the Iwerks, Harman-Ising and in-house productions, at least in terms of promotions in the theaters.

I do not think there is any reason to believe that these findings (or similar findings) would have been unique to the Loew’s New York City theaters, but likely could be applied to other chains’ operations all over the United States in this period.

E.O. Costello is a New York-based attorney, whose love of history has led him to study, in depth, the cartoons of the 1940s and the historical and pop-culture references contained in them. He has written for Animato!, APAtoons, and was the creator of The Warner Bros. Cartoon Companion.

E.O. Costello is a New York-based attorney, whose love of history has led him to study, in depth, the cartoons of the 1940s and the historical and pop-culture references contained in them. He has written for Animato!, APAtoons, and was the creator of The Warner Bros. Cartoon Companion.

I admire the circumspect language of your conclusion, as it’s not possible to extrapolate general trends from a single case study. It would would be interesting to see if any additional information about cartoon distribution to other cinema chains in other regions might bear out your findings. This is an excellent baseline to further research into a hitherto neglected subject.

I do know that RKO published a similar series of fliers for its NYC theaters during the same period — this post shows one of the later ones, for “Snow White,” and if one could find a run similar to the one I found, one could expand it. But yes, I did have to be very careful in making conclusions from just one group of theaters in one major market.

I’m feeling sorry for Warner Bros. here. Certainly someone must have been showing all those Porky, Egghead and Sniffles cartoons!

I’ve had an interest in the Skippy cartoon ever since I first read about it on Don M. Yowp’s Tralfaz blog, particularly the fact that United Artists did try for animation immediately after Disney left for RKO. I’d always wondered why UA didn’t pick up the Van Beuren cartoons. I guess that they decided that Mayfair would make better cartoons than what the Rainbow Parade was turning out – for all the good that did them, given Mayfair went belly-up soon afterwards. Still, at least they did get one cartoon out and apparently seen by the public, even if only by a small percentage of it. Personally, I’m just glad to know a copy exists, and given the Library of Congress’s excellent track record of restoring old films, there’s a chance that Skippy short will see the light of day for the first time in over eight decades.

At any rate, it looks like UA largely gave up on animation for the next several years, Victory Through Air Power aside. They did have some brief deals through the next couple of decades with the likes of John Sutherland and Walter Lantz, but it wasn’t until 1964 when they signed a deal for animated shorts that stuck, thanks DePatie Freleng; ironic, as the theatrical animated short as a mainstream commodity was in terminal decline at that point.

It’s hard to say precisely what happened, but I get the impression that van Beuren collapsed, hard, right after losing the contract with RKO, and didn’t survive long enough to be picked up by UA. UA had fairly limited resources, and a rather upscale image — I’ve had a feeling that’s why they were comfortable with Disney — and van Beuren might not have been “class” enough for them. (Doesn’t necessarily explain their venture with Lantz, later.)

This might sound kinda random, but I have a theory that Maroon Cartoons ( in “Roger Rabbit” ) were distributed by UA.

or it could’ve been another fictional film company/distributor, but it’s weird that no distributor is mentioned at the start of the Baby Herman cartoon and it’s unlikely the studio could self-distributed their cartoons at the time.