Some things you may not know about film, why things are the way they are, and why film continues to be so important!

Perhaps the one most important thing to know about preservation is that there really is no perfect preservation, and no perfect media. Collectively, we’re up against really tough odds in preserving the history of film in that every medium has it’s troubles. As technology advances, interestingly, we trade our old preservation problems for a set of entirely brand new ones. The digital age produces the ability to preserve materials more efficiently space-wise and with much less expense, but also leaves us with formats known to have issues in much shorter lifespans.

For the Thunderbean DVDs and Blu-rays, we have been transferring and doing digital restoration to materials in HD. While these are now available to be seen and appreciated in good quality, this is far from true archival preservation. Interestingly though, it is now leading in that direction, with some of the materials we’ve been using now actually being preserved on film thanks to the success of the latest titles.

Film continues to be a hugely valuable archival format, even well into this new era. Years back, I remember doing a job where we were using the same studio as Warner Brothers to finish the cel work, and learned that Warner Brothers continued to do all their jobs on cels so they could be shot in 35mm rather than computer colored (in standard definition back then). They said they did this for archival reasons. I’m sure they’re glad they did now; it gives this TV library of animation a much higher quality second life with time and resources in re-transfer and editing.

Film continues to be a hugely valuable archival format, even well into this new era. Years back, I remember doing a job where we were using the same studio as Warner Brothers to finish the cel work, and learned that Warner Brothers continued to do all their jobs on cels so they could be shot in 35mm rather than computer colored (in standard definition back then). They said they did this for archival reasons. I’m sure they’re glad they did now; it gives this TV library of animation a much higher quality second life with time and resources in re-transfer and editing.

Many companies are not as smart in preserving their materials. Only a few years ago, the entire Filmation catalog was transferred to HD by the owners of the library, who then had all the original materials destroyed; they sent to a silver recovery lab to save the archiving space. The highest quality that will exist on this material is however they transferred them to HD.

As material is passed from one company to another, often mistakes are made, materials turn up missing, and the material continues it’s slow march back to the earth. Materials internally belonging to a company can be mislabeled or mistaken.

You would think in these more modern times that the collections that managed to survive all these years have made it past danger and are now in safe hands. When people who have expert knowledge in the area of a certain collection are involved, these mistakes can often be avoided- but even the biggest companies can make big mistakes. I was amazed to find out that one of the most famous companies with a large animation library tossed much of its nitrate materials with original titles within the last 20 years or so, thinking that the original materials contained complete versions and, therefore, there was no need to keep all those extra reels. Another large company had made time-coded versions of many cartoons in one series, but when it went to look for a few key titles it had transferred, they were now gone entirely. I’m experiencing this as well right now, trying to track down versions of several cartoons that have a specific title card on them that were transferred 20-some years ago, only to discover it doesn’t seem to exist on the master materials at their respective archives.

So, what are ‘master materials’ anyway?

The simple answer: whatever the best materials are that still exist. If you went to hunt for the ‘original materials’ on old films, you’re met with a series of possible options on some films, a single option on others, and the hunt doesn’t stop with just knowing what material exists- an evaluation needs to be often done to figure out what material is the best option to use to yield the best results.

On the current project I’m working on, 35mm materials exist on most of the titles, while some of them only have 16mm prints and negatives. Sometimes the original negative is extant, though often that material has seen its share of wear, and ALL had the original titles missing entirely, if any titles were on the neg at all. The newer versions were often edited as well, removing some of the more outrageous and racy gags for reissue in the 40s. Clearly, the original neg, though the highest quality, is not the best choice for a complete version of the film.

Often, the master positive material is a better option if it exists. This is a ‘master’ print that is made from the original negative. That print (often called the fine grain master positive) is then used to make what is called a duplicate negative. THAT negative is then used to make the release prints. If the Fine Grain is still around, it’s often the one piece of material on a film that hasn’t seen much action, and is therefore in pristine condition. These are sometimes called a ‘protection’ print. In the 30s, Kodak often printed this material on a blue-tinted stock. Sometimes these materials are referred to as ‘lavenders’. The lavenders on this particular series are a thing of beauty when they are extant, with complete original titles and not a scratch or edit to be found. ‘Lavenders’ were on Nitrate-based stock, and only made for black and white films, and discontinued when Kodak switched to all-safety film stocks in the late 40s.

Often, the master positive material is a better option if it exists. This is a ‘master’ print that is made from the original negative. That print (often called the fine grain master positive) is then used to make what is called a duplicate negative. THAT negative is then used to make the release prints. If the Fine Grain is still around, it’s often the one piece of material on a film that hasn’t seen much action, and is therefore in pristine condition. These are sometimes called a ‘protection’ print. In the 30s, Kodak often printed this material on a blue-tinted stock. Sometimes these materials are referred to as ‘lavenders’. The lavenders on this particular series are a thing of beauty when they are extant, with complete original titles and not a scratch or edit to be found. ‘Lavenders’ were on Nitrate-based stock, and only made for black and white films, and discontinued when Kodak switched to all-safety film stocks in the late 40s.

These days, with the advent of Blu-ray, there is more information available, but I’ve found that the basics described above seem confusing without a basic explanation. I hope this makes it at least a little easier to understand when you hear a few of these terms!

It would be nice at some point to highlight some of the collectors and archivists in this space. They’re the true heros of preservation, allowing these things to continue to exist and given availability for transfer.

Here is a neat article by Ken Weissman showing how the Library of Congress preserves and stores it’s films.

..and a neat little article showing a well-loved nitrate print of A Star is Born.

And, since there has been no cartoon this week so far, we need to show SOMETHING, so, here is the first Flip the Frog cartoon, for no better reason other than to show it. Notice the lack of an MGM title on this color release print. Wouldn’t it be nice if some of the other Flip the Frogs made in color surfaced too?

Steve Stanchfield is an animator, educator and film archivist. He runs Thunderbean Animation, an animation studio in Ann Arbor, Michigan and has compiled over a dozen archival animation DVD collections devoted to such subjects at Private Snafu, The Little King and the infamous Cubby Bear. Steve is also a professor at the College for Creative Studies in Detroit.

Steve Stanchfield is an animator, educator and film archivist. He runs Thunderbean Animation, an animation studio in Ann Arbor, Michigan and has compiled over a dozen archival animation DVD collections devoted to such subjects at Private Snafu, The Little King and the infamous Cubby Bear. Steve is also a professor at the College for Creative Studies in Detroit.

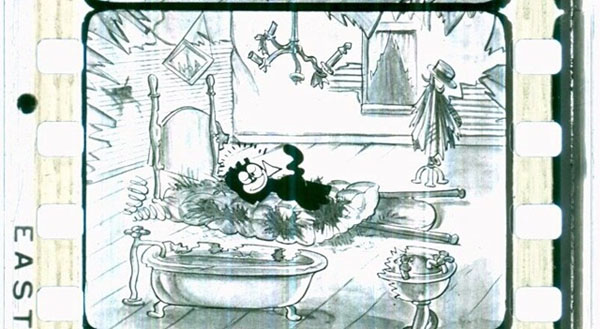

What cartoon is the frame at the top from… looks like a Winkler Krazy…

A HUNGER STROKE (1927):

https://www.flickr.com/photos/nfig/sets/72157610917051882/

Really dig that sketchy background!

“Leave us not mince woids here,” as Sheldon Leonard might’ve said; the company that destroyed the Filmation originals was Hallmark Cards, Inc; and only a third-party intervention prevented them from doing the same with the Hal Roach Laurel and Hardy negatives! (Documentation of this may be found at http://www.laurel-and-hardy.com) “When you care enough,” right?

Interesting how much Flip the Frog’s design changed during his short run, from this very froglike first version whose “arms” seem to come out of his head, to the generic-30’s-character look that was a frog because that”s what the title card said he was…

Honestly, if it’s a choice between the legacies of Hal Roach and Lou Scheimer… Haul those Fat Alberts and Quackulas over here, I’ll start the fire.

Ok, you kinda got a point there.

…except that the Quackula shorts are owned by Vitacom (they were part of the Heckle and Jeckle Filmation series) and would’ve not been included with the Filmation library.

That’s great news about the Filmation negatives, Steve! Their stuff was utter junk that doesn’t deserve preservation. Better the money spent to preserve cartoon cinema go to the preservation of Ub Iwerks and Charles Mintz material.

Say, didn’t you work at Filmation?

I’m with Mark. My only regret is that there wasn’t a Filmation melting party. EVERYone who worked at that place would’ve turned out for it—many of them to help stoke the fire.

Thad…You’re usage of hyperbole sometimes goes a LITTLE too overboard for me. “My only regret is that there wasn’t a Filmation melting party. EVERYone who worked at that place would’ve turned out for it—many of them to help stoke the fire.” Really?

Yes, I worked at Filmation in the summer of 1968. I worked about two months before going back to school. I’ve told most of my favorite stories about the place over at the TAG Union oral histories. Worst people there: Rocky Benedict, production manager, Lou Scheimer and Norm Prescott, big bosses. Hal Sutherland wasn’t too bad. I met the great Virgil Ross there, Tolly Kirsarnoff was a director. Tolly loved to hide out from the big bosses. I’m so glad future generations will be spared the horrible Archie series we did, and the Batman/Superman hours.

I’ll take the Filmation version of Sabrina the Teenage Witch over the Melissa Joan Hart version anyday. (Though I don’t mind the newer animated version that Savage Steve Holland had a hand in.)

Now that all you throbbing geniuses are through snarking about Filmation, I’m sure you also refused to cash all those nice fat union paychecks you made while slumming there on work so far below your magnificent talents. Yeah, right. I didn’t think so.

I spent nearly twelve years working at a Hallmark Cards plant in Duluth, Minnesota. Even at the end, I hadn’t cracked ten bucks an hour. Our department worked on shifts just long enough not to qualify as full time work. No benefits until near the end, and even then a second-rate plan inferior to the front office and the other departments there. And finally, they automated our jobs (some people had worked there even longer than I had) and offshored them to India.

And Hallmark hides behind their ooey-gooey, warm-and-fuzzy public image, much like that well-known mouse factory. Too bad my gut can’t possibly hold as much as I want to puke. As Billy Joel wrote, go on and cry in your coffee but don’t come bitchin’ to me.

Hallmark and Disney are evil, but Filmation was a different kind of evil because the company produced nothing but junk yet still created this misplaced nationalistic pride that its legacy is worth defending because it kept jobs in the U.S. by reusing the same three pieces of animation over and over. You can still hate Hallmark (threatening the Laurel & Hardy materials is a good enough reason) and be apathetic to the fact that the materials of the worst animation studio of all time are gone. Not every frame is worth saving.

Ok, I agree that the studio wasn’t very good. But saying that they deserved to have their negatives burned and they don’t deserve preservation?!? That’s a very insensitive thing for you to say Thad and Mark (really enjoy some of your posts, but still).

Also, summing up the studio as making “ONLY JUNK” is a big generalization.

One more thing. “[Filmation] still created this misplaced nationalistic pride that its legacy is worth defending because it kept jobs in the U.S. by reusing the same three pieces of animation over and over. ”

Mark Evanier probably summed it up best:

“First off, it’s commendable for anyone to want to maintain some sort of control and responsibility for their product. Filmation operated at a time when it was difficult to produce cartoon shows; when network restrictions, interference, schedules and budgets saddled everyone with enormous handicaps. That’s why there weren’t a couple of studios doing vastly superior shows for Saturday morning TV. The game was rigged against everyone.

To all the other handicaps, every studio except Filmation added an additional one out of simple greed: They would have the animation work done wherever it could be done the cheapest. If that meant laying off people in L.A. and exporting their jobs to Korea, fine. That usually meant that they never knew what the hell they were going to get back. Heck, in some cases, they never even knew who was going to do the work or where it would actually be done…because the studio in Korea might outsource the work to a studio in Manila which would then job ink-and-paint out to some kids in a grass hut in Botswana. In some cases, the trail might be filled with kickbacks and skimming and bribes and all manner of dubious financial ethics. I like that Lou refused to participate in that often-corrupt system.

I believe I disagree with Amid that some Asian subcontractors of that period did notably superior work. He’d have to tell me which ones he has in mind because at the moment, I sure can’t think of any shows done back then by Hanna-Barbera or DePatie-Freleng or Ruby-Spears or anyone that went overseas and came back looking great. If there were any, it was probably by dumb luck. More likely, it was by keeping some key elements of production in-house and local.

This is not because American animators are or were any better or more deserving of the work. It’s simply a matter of not fragmenting the process and having key parts of the assembly line done in other lands by people who lacked a common language. At Filmation, writers could walk down the hall and talk to animators and vice-versa. I believe there were times when that elevated the product a bit.

It sure as heck beat out the situation we too-often had on shows animated overseas, which is that when it came time to assemble an episode for broadcast, key scenes were missing because retakes had never arrived from India or wherever. There’s more to a cartoon show than whether the animation looks good. It also has to be there.

So I think it’s commendable that Scheimer kept production on Reseda Boulevard and didn’t surrender it to that crapshoot…because that’s pretty much what it was back then. It might come back better but it also sometimes came back worse or incomplete, not because the artists 6000 miles away were bad or because they were not American but because they were 6000 miles away.

It is also commendable that Lou kept work here because the current animation industry would not be what it is today if there had been a lot less work in this town in the seventies. Many people who now produce fine animation would have gone into other occupations. The opportunity to break in on less-than-wonderful shows has a lot to do with them being around (and experienced enough) to later do wonderful shows. That folks are able to continuously make a living is vital in a field like this. Scheimer and Prescott gave a lot of new kids a chance to work in animation, as opposed to the alternative, which in most cases was to not work in animation. They also gave a lot of old-timers and veterans a place to earn a living in cartoons when no one else was hiring.”

Just saying. I also don’t like Filmation shows too, but you went a bit too extreme.

Even as a child, I can’t remember a single, solitary time I ever genuinely enjoyed a Filmation cartoon. Not even Fat Albert when NBC reran it in the 1980s, and I imagine it’ll be awhile, if ever, before that’s ever rerun again. The worst of Disney and WB was still better than what they could crank out, and frankly, even Hanna-Barbera’s characters had more appeal. That’s how bad these shows were.

But on principle, I cannot celebrate the deliberate destruction of intellectual property at corporate hands, no matter how bad it was.

Then again, Mark said this about Rankin Bass on the Tralfaz blog: “In my foolish youth I used to call the production companies, “Rank and Base” and “Videocrap Intenational”. Now I just say, “Burn the Negatives”!”

So…make of that what you will.

http://www.filmpreservation.org/dvds-and-books/the-film-preservation-guide-download

http://www.filmpreservation.org/userfiles/image/PDFs/fpg.pdf

A local collector and preservationist ran his collection of very early prints, some from the silent era including a good number by

Ladislaw Starewicz (sorry, forgot to say – all were animation). ‘Local’ is Indianapolis, some 4 1/2 hours south of you. You may want to connect and swap stories? If you don’t already know him, his website is here: http://www.filmeric.com/index.html.

The Filmation news is stunning. Very shortsighted. Last year I learned that Gravity only exists in 2K. In two years it will already be dated.

Filmation routinely shot their animation on ‘short ends’ of Eastmancolor negative film, to keep from having to buy whole reels of negative film all the time. It saved money but arguably made the color correction process more difficult due to wildly differing batches (and ages) of emulsion being processed together. Filmation could not have imagined the day when the most valuable part of their studio – the film library – would be destroyed in the name of efficiency, though in their case it is ironic.

Don’t some of the shows not owned by Filmation still exist in film copies, like perhaps the animated Star Trek, the Mighty Mouse and Heckle and Jeckle show or The Tom and Jerry Comedy Show?

I would assume those would be, along with the DC Comics stuff.

There’s also:

“The Brady Kids” (Paramount)

“My Favorite Martians” (either WB or Jack Chertok Productions)

“The New Adventures of Gilligan” (WB)

“Gilligan’s Planet” (WB)

“SHAZAM!” (live-action and animated versions) (WB)

“Fantastic Voyage” (Fox)

“Journey to the Center of the Earth” (Fox)

(Not sure if Archie Comics has the negatives for the various Archie and Sabrina cartoons, or who has the rights to “Lassie’s Rescue Rangers” and the animated versions of Tarzan and the Lone Ranger.)

From what I’ve read, until circa the 1970s, release prints (or, in the case of dye-transfer Technicolor, printing matrices used to strike prints) were almost always printed directly from the camera negative. There wasn’t a large number of prints made for a release (maybe a couple/few hundred, or less), so the wear to the camera negative was considered negligible. Master positives, then, would have been made as backup elements. Then the demand for prints went up considerably and the increase in wear to the camera negative from the large number of prints needed would have been unacceptable, so the camera negative > master positive > dupe negative > release print process became the norm.

The negs for B/W prints were used for printdowns to 16mm sometimes; I’ve heard that Universals negs were beat up making TV prints, though it seems like the original neg wouldn’t usually be used for that. For Technicolor, the matrices are a separate printing element for each color, so they wouldn’t have used the ‘original’ camera neg for any of those prints since the matrice is a different type of material (think printing plate).

Cool article Steve! Just out of curiosity how many of the “Flip the Frog” cartoons were made in color? I I’ve read that “Techno Cracked” was, but am unfamiliar with others.

I wonder if “Flying Fists” was either filmed in color, or at least painted to be filmed in color, since Flip’s body is gray instead of black.

Flying Fists was made in color. So was Puddle Pranks and Little Orphan Willie…