Woody Woodpecker’s 1944 cartoon The Barber of Seville is a dizzying display of cartoon comedy and animation artistry.

It’s easy to see why The Barber of Seville was counted among The 50 Greatest Cartoons in Jerry Beck’s 1994 book of the same name (Barber came in at number 43). In the book, contributor Joe Adamson wrote, “We can still ask the logical questions, but rather than just evade them, Woody in The Barber of Seville is transcending them, making himself an understandable personality, if never quite an explicable one, and one of the greatest cartoon characters of Hollywood animation’s golden age, even if he was all cartoon and no character.”

It’s easy to see why The Barber of Seville was counted among The 50 Greatest Cartoons in Jerry Beck’s 1994 book of the same name (Barber came in at number 43). In the book, contributor Joe Adamson wrote, “We can still ask the logical questions, but rather than just evade them, Woody in The Barber of Seville is transcending them, making himself an understandable personality, if never quite an explicable one, and one of the greatest cartoon characters of Hollywood animation’s golden age, even if he was all cartoon and no character.”

The Barber of Seville, celebrating its 80th anniversary this year, marks the first time Woody would make his soon-to-be iconic opening before the credits, where he pops out of a log and exclaims, “Guess who?!?”

As the short begins, Walter Lantz’s iconic character takes on the title role. Woody arrives at the “Seville Barber Shop, Tony Figaro, Prop.” The woodpecker goes inside for a haircut, only to find that Tony isn’t there and has left a sign: “Gone to take my physical. Back soon” (the song “You’re in the Army Now” plays on the soundtrack indicating what physical Tony is taking).

As the short begins, Walter Lantz’s iconic character takes on the title role. Woody arrives at the “Seville Barber Shop, Tony Figaro, Prop.” The woodpecker goes inside for a haircut, only to find that Tony isn’t there and has left a sign: “Gone to take my physical. Back soon” (the song “You’re in the Army Now” plays on the soundtrack indicating what physical Tony is taking).

Woody takes Tony’s place and assists the next two customers entering the barbershop. One is a Native American, and the next is an Italian construction worker (neither character is portrayed sensitively).

For the Native American, Woody places hot towels on his feathered headdress, turning it into a badminton birdie. Angered, the Native American threatens to give Woody the “scalp treatment,” but Woody knocks him out, after which the Native American is launched from his chair, landing across the street, where he stands in front of a tobacco store like a statue.

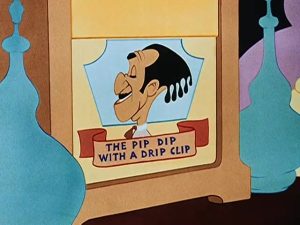

The construction worker comes in next and, after Woody removes his helmet with a welding torch and begins singing “Largo al factotum,” from Gioachino Rossini’s opera, The Barber of Seville, he lathers up the customer’s face and shoes.

The construction worker comes in next and, after Woody removes his helmet with a welding torch and begins singing “Largo al factotum,” from Gioachino Rossini’s opera, The Barber of Seville, he lathers up the customer’s face and shoes.

As the music speeds up, Woody pulls out an imposing shaving blade and begins swinging it like a sword as the terrified construction worker ducks out of the way and eventually hides. Woody begins calling for him (“Figaro! Figaro!”), and the worker replies, “Coming, mother!” in reference to the popular The Aldrich Family radio show of the time.

Woody, giant blade in hand, then chases the man throughout the barber shop, destroying everything in his midst. Finally getting his customer back in the chair, Woody lathers, shaves, and applies aftershave as the fast-paced animation matches the sped-up music.

He chases the construction worker out of the shop and launches into his trademark Woody Woodpecker laugh, after which the gentleman throws Woody through the front window, back into the shop, where the woodpecker takes out a shelf of shaving mugs and the barber pole falls on him, trapping woody inside.

He chases the construction worker out of the shop and launches into his trademark Woody Woodpecker laugh, after which the gentleman throws Woody through the front window, back into the shop, where the woodpecker takes out a shelf of shaving mugs and the barber pole falls on him, trapping woody inside.

The Barber of Seville was directed by the legendary James “Shamus” Culhane (the first of many Woody shorts he would helm). In his autobiography, Talking Animals and Other People, Culhane discusses how he studied film, reading books such as Film Technique and Film Acting by Vsevolod Pudovkin and The Film Sense by Sergei Eisenstein.

He brought what he had learned to The Barber of Seville, trying new approaches to animation filmmaking. Culhane wrote in his book: “The tempo more than doubled in the reprise, and following the phrasing note for note, I had Woody repeat all of his former antics at a frenzied pace. Some of the shots were six exposures long or a quarter of a second. In one scene, the tempo was so fast that I split Woody into multiple images, all yelling ‘Figaro!’’

There’s also an infectious energy toward the end of The Barber of Seville as Woody chases the construction worker through the shop, and there’s a sense of non-stop motion as the two continuously knock bottles off shelves.

There’s also an infectious energy toward the end of The Barber of Seville as Woody chases the construction worker through the shop, and there’s a sense of non-stop motion as the two continuously knock bottles off shelves.

Along with Culhane on this wild Woody ride were fellow legends, such as animators Laverne Harding and Les Kline, background artist Philip DeGuard, and story artists Ben Hardaway and Milt Schaffer.

Another animation legend was also responsible for making a change to Woody’s look with The Barber of Seville, as Leonard Maltin noted in his book, Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons: “Layout man and color stylist Art Heinemann suggested that he [Woody] be redesigned to make him less grotesque and more appealing. Lantz agreed, and Heineman replaced the many garish colors with a simple combination of red hair, white belly, and yellow beak.”

With this new look, the character of Woody Woodpecker in The Barber of Seville is, once again, best described by Adamson in The 50 Greatest Cartoons as “… a Technicolor synapse between shadow and substance, between ourselves and our more outrageous fantasies.”

Devon Baxter did one of his wonderful breakdown posts for The Barber of Seville [Click HERE]; and Tom Klein speaks about the modernism in the film [Click HERE].

Michael Lyons is a freelance writer, specializing in film, television, and pop culture. He is the author of the book, Drawn to Greatness: Disney’s Animation Renaissance, which chronicles the amazing growth at the Disney animation studio in the 1990s. In addition to Animation Scoop and Cartoon Research, he has contributed to Remind Magazine, Cinefantastique, Animation World Network and Disney Magazine. He also writes a blog, Screen Saver: A Retro Review of TV Shows and Movies of Yesteryear and his interviews with a number of animation legends have been featured in several volumes of the books, Walt’s People. You can visit Michael’s web site Words From Lyons at:

Michael Lyons is a freelance writer, specializing in film, television, and pop culture. He is the author of the book, Drawn to Greatness: Disney’s Animation Renaissance, which chronicles the amazing growth at the Disney animation studio in the 1990s. In addition to Animation Scoop and Cartoon Research, he has contributed to Remind Magazine, Cinefantastique, Animation World Network and Disney Magazine. He also writes a blog, Screen Saver: A Retro Review of TV Shows and Movies of Yesteryear and his interviews with a number of animation legends have been featured in several volumes of the books, Walt’s People. You can visit Michael’s web site Words From Lyons at:

Ah, bravo, Figaro! Bravo! Bravissimo!

I never saw this cartoon when I was growing up. Rossini’s “The Barber of Seville” was one of the first operas I ever saw, and I would have remembered if I had ever heard Woody Woodpecker sing “Largo al factotum”. It first came to my attention with Jerry Beck’s 50 Greatest Cartoons book, and when I read about it I thought: “How on earth did I manage to miss out on this one?” I finally found it on a video collection, and of course I loved it; Culhane’s Woody cartoons of the mid-1940s arguably represent the character at his zenith. By this time, however, I was well into my thirties; and because I hadn’t grown up with it, “The Barber of Seville” will never hold the same place in my heart that “The Rabbit of Seville” does.

I get a big laugh when Woody sports Veronica Lake’s peekaboo hairstyle. Why? Because “Veronica Lake” is what my parents used to call me when they thought I needed a haircut!

As for “Scalp Treatment”, by coincidence that’s the title of the last cartoon that Walter Lantz directed personally, in 1952. Here Woody is the customer in Buzz Buzzard’s barber shop, and everything is amicable until the two of them start to vie for the attentions of the beautiful native princess Sitting Pretty.

By a further coincidence, the Terrytoon “The Butcher of Seville” was released three months before Lantz’s “The Barber of Seville” in 1944. It’s a fun cartoon, with a great musical score and some amusing jabs at wartime rationing. I don’t suppose there’s any chance of an 80th anniversary “Cel-ebration” of that one, is there? Didn’t think so….

Lantz’s finest moment. A perfect Golden Age cartoon.

If I had to pick one standout from the assembled formidable star-power creators of this short, it would have to be Art Heinemann.

A HollyWood makeover for the ages.

“Rabbit Rhapsody” is said to be purely coincidental after “Cat Concerto.” Could the same be said about “Rabbit of Seville”?

If you’re interested in the controversy over “Rhapsody Rabbit” vs. “The Cat Concerto”, Thad Komorowski wrote an excellent article laying out nearly all the known evidence on the sequence of events: https://cartoonresearch.com/index.php/pianist-envy/

I’d say so. Haircuts are something that most men periodically undergo, so it’s not surprising that there are a fair few cartoons set in barbershops. Rossini’s “The Barber of Seville” is a pretty obvious choice for a musical underscore in such a setting — even “Seinfeld” used it that context — though the Heckle and Jeckle cartoon “Hair Cut-Ups” uses Mozart’s “The Marriage of Figaro” overture. At least “A Clean Shaven Man” had an original song.

If there was a cartoon from Lantz that could be its G.O.A.T. The Barber of Seville is it. With its energy, music and timing, this amazing, animated feature with Woody Woodpecker is packed with craziness and the aforementioned new look for Woody to what many of us would know him for many years to come.

My first seeing of this was on TV…New York’s Channel 5 in the 1980’s. The DVD’s and now MeTV makes those memories return.

Although I’ll say between the two, I prefer Rabbit of Seville, but the pacing of this cartoon just goes all in, I laughed more with it. I think Joe Adamson described Woody the best in that he is ‘all cartoon and no character’ that the humor still clicks. As for what Leonard Maltin wrote, in of Mice and Magic, ‘grotesque’ is definitely the best word to describe Woody’s original design, plus after seeing some of the early cartoons, I find it didn’t really lend itself well to animation. Glad Walter Lantz concurred with Art Heinemann to create a redesign.