In 1961, after the American box office failure of Tōei Dōga’s first three animated features, Japanese theatrical animation was relegated to being sold as children’s cartoons in the U.S. – either for theatrical Saturday “kiddie show” matinees, which were common at the time, or distributed simply as TV movies for children.

The next few Japanese theatrical features seemed to confirm this, with stories that were either overly ethnically Japanese (Anju to Zushio-maru/The Littlest Warrior, 1961), or were overly juvenile (Gulliver no Uchu Ryoko/Gulliver’s Travels Beyond the Moon, 1965). One, Wan Wan Chushingura (The Woof Woof 47 Ronin), 1963, was so heavily historically Japanese that nobody has ever tried to adapt it for American audiences, despite Tōei Dōga’s assigning an English-language title (Doggie March) for it (click sales brochure cover, thumbnail at right, to enlarge). It is the famous (in Japan) story of the 47 Rōnin, which happened in 1701-1703 and ends with all 47 samurai committing seppuku (hardly a children’s story), retold for children with an anthropomorphized dog cast instead of human feudal samurai.

The next few Japanese theatrical features seemed to confirm this, with stories that were either overly ethnically Japanese (Anju to Zushio-maru/The Littlest Warrior, 1961), or were overly juvenile (Gulliver no Uchu Ryoko/Gulliver’s Travels Beyond the Moon, 1965). One, Wan Wan Chushingura (The Woof Woof 47 Ronin), 1963, was so heavily historically Japanese that nobody has ever tried to adapt it for American audiences, despite Tōei Dōga’s assigning an English-language title (Doggie March) for it (click sales brochure cover, thumbnail at right, to enlarge). It is the famous (in Japan) story of the 47 Rōnin, which happened in 1701-1703 and ends with all 47 samurai committing seppuku (hardly a children’s story), retold for children with an anthropomorphized dog cast instead of human feudal samurai.

However, this unfortunately swept away three theatrical features that, with the proper promotion in America, could have been very successful all-ages theatrical releases.

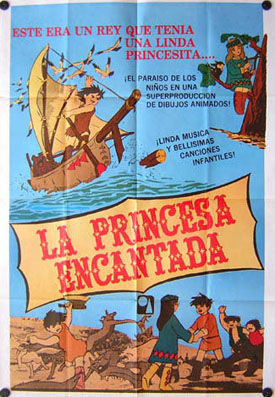

The earliest of these was Tōei Dōga’s Wanpaku Ôji no Orochi Taiji/The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon; released on March 24, 1963 in Japan, and by Columbia Pictures on January 1, 1964 in America. It was marketed in America as a Japanese fairy tale. It was more than that; it was a portmanteau, bowdlerized for children, of probably the three most well-known Shintō myths, written down in the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki about 700 A.D. but orally much older. In the myths, Susanō is the youngest son of the principal Japanese gods, Izanagi and Izanami, the creators of the earth and of humanity. Susanō is the adult storm god and the Shintō equivalent of Loki, strong and brave but very hot-tempered and headstrong; a troublemaker and god of chaos.

In The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon, he is Prince Susanō, the youngest son of King Izanagi and Queen Izanami, about eight to ten years old. He plays with animal companions, principally Akahana (“Red Nose”), the talking black rabbit. One day, his mother disappears. When he asks where she is, his father tells him that she “has gone to another place”. The audience understands that this is a euphemism meaning that she has died, but Susanō takes it literally and throws a temper tantrum, swearing to find her and bring her home. Susanō builds a boat and sails with Akahana to the Crystal Palace, the court of his older brother, Tsukuyomi, in the Land of Night (the moon and the Shintō moon god). When he does not find her there, he throws another tantrum and destroys part of the moon court. Despite this, Tsukuyomi gives him a magic ice crystal and sends him on to their younger brother, the fire god. Susanō fights him, too, defeating him with the magic ice crystal and Akahana’s help. While in the Land of Fire, Susanō gets another companion, the Titan Bō, a friendly fire giant. Next, the three continue on to the Land of Light, the kingdom of Susanō’s older sister Amaterasu (the Shintō sun goddess). Susanō again “accidentally” destroys part of her court. Amaterasu, frightened, hides in a cave, plunging the world into darkness. The inhabitants of the Land of Light throw a big party outside the cave to lure her out. (In Shintō mythology, they throw a pornographic orgy.) Finally, the three go to Japan’s Izumo Province, where Susanō meets Princess Kushinada, a little girl his own age. She tells him how Izumo is being terrorized by Yamata no Orochi, the eight-headed dragon who has already eaten her seven sisters. Susanō pledges to kill the dragon, with the help of Akahana and Bō, and a flying horse sent by Amaterasu. At the end, Susanō’s mother’s spirit returns briefly to tell him that she cannot return with him, but he no longer cares so much because he has fallen in love with Kushinada and resolved to stay in her country.

In The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon, he is Prince Susanō, the youngest son of King Izanagi and Queen Izanami, about eight to ten years old. He plays with animal companions, principally Akahana (“Red Nose”), the talking black rabbit. One day, his mother disappears. When he asks where she is, his father tells him that she “has gone to another place”. The audience understands that this is a euphemism meaning that she has died, but Susanō takes it literally and throws a temper tantrum, swearing to find her and bring her home. Susanō builds a boat and sails with Akahana to the Crystal Palace, the court of his older brother, Tsukuyomi, in the Land of Night (the moon and the Shintō moon god). When he does not find her there, he throws another tantrum and destroys part of the moon court. Despite this, Tsukuyomi gives him a magic ice crystal and sends him on to their younger brother, the fire god. Susanō fights him, too, defeating him with the magic ice crystal and Akahana’s help. While in the Land of Fire, Susanō gets another companion, the Titan Bō, a friendly fire giant. Next, the three continue on to the Land of Light, the kingdom of Susanō’s older sister Amaterasu (the Shintō sun goddess). Susanō again “accidentally” destroys part of her court. Amaterasu, frightened, hides in a cave, plunging the world into darkness. The inhabitants of the Land of Light throw a big party outside the cave to lure her out. (In Shintō mythology, they throw a pornographic orgy.) Finally, the three go to Japan’s Izumo Province, where Susanō meets Princess Kushinada, a little girl his own age. She tells him how Izumo is being terrorized by Yamata no Orochi, the eight-headed dragon who has already eaten her seven sisters. Susanō pledges to kill the dragon, with the help of Akahana and Bō, and a flying horse sent by Amaterasu. At the end, Susanō’s mother’s spirit returns briefly to tell him that she cannot return with him, but he no longer cares so much because he has fallen in love with Kushinada and resolved to stay in her country.

The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon was the most advanced Japanese animated feature up to this time. Tōei Dōga had finished practicing the basics of theatrical cartoon animation and was ready to experiment under director Yūgo Serikawa with something new. The plot was juvenilized, but the art direction by animation director Yasuji Mori abandoned the naturalistic, soft Disney look and emphasized modernist, stylized, almost abstract art in both the background and character design. The color, also abandoning traditional Disney, is in blocks of bright, primary hues. The characters exhibit no black outlines or shading. The feature was the first filmed in Tōei Dōga’s TōeiScope anamorphic widescreen format, similar to CinemaScope in America. Tōei Dōga spent money on it, commissioning composer Akira Ifukube, best-known for his Godzilla score, to write the music. (No monster-movie fan will fail to recognize’s Ifukube’s distinct music, which is clear on the Japanese trailer.) The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon marked the emphasizing of several filmmakers who would become famous in the anime industry; notably assistant directors Isao Takahata and Kimio Yabuki, and key animators Yasuo Ōtsuka and Yōichi Kotabe.

The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon was the most advanced Japanese animated feature up to this time. Tōei Dōga had finished practicing the basics of theatrical cartoon animation and was ready to experiment under director Yūgo Serikawa with something new. The plot was juvenilized, but the art direction by animation director Yasuji Mori abandoned the naturalistic, soft Disney look and emphasized modernist, stylized, almost abstract art in both the background and character design. The color, also abandoning traditional Disney, is in blocks of bright, primary hues. The characters exhibit no black outlines or shading. The feature was the first filmed in Tōei Dōga’s TōeiScope anamorphic widescreen format, similar to CinemaScope in America. Tōei Dōga spent money on it, commissioning composer Akira Ifukube, best-known for his Godzilla score, to write the music. (No monster-movie fan will fail to recognize’s Ifukube’s distinct music, which is clear on the Japanese trailer.) The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon marked the emphasizing of several filmmakers who would become famous in the anime industry; notably assistant directors Isao Takahata and Kimio Yabuki, and key animators Yasuo Ōtsuka and Yōichi Kotabe.

The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon received accolades in Japan and internationally. It got the 1963 Mainichi Film Awards’ Noburō Ōfuji Award for excellence in animation; the only theatrical feature to win it until Hayao Miyazaki’s Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro (1979). It was officially recommended by both the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health’s Central Child Welfare Council. The Venice Film Festival gave it the Bronze Oscella (presumably for screenwriting).

In America, it was released by Columbia Pictures as a children’s matinee feature. Wikipedia (edited): “Its Japanese origin was downplayed, as was standard practice at the time, with William Ross, the director of the English dubbing, credited as director, and Tōei’s Fujicolor and TōeiScope widescreen processes rebranded as “MagiColor” and “WonderScope” respectively.” It received little critical notice at the time, though recently American director Genndy Tartakovsky has acknowledged it as a major influence on his 2001-2004 Emmy- and Annie-award-winning TV series Samurai Jack.

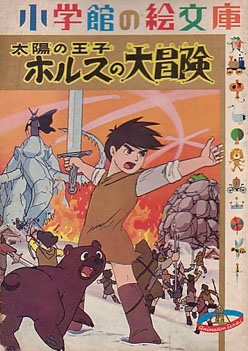

The second of these was Tōei Dōga’s Taiyō no Ōji: Horusu no Daibōken (The Sun Prince – Hols’ Great Adventure); 82 minutes, released on July 21, 1968 in Japan, and by American International Pictures Television as The Little Norse Prince in 1970. Was it originally prepared for a theatrical release? The MGM theatrical logo in front of AIP’s, and the quality of the American dub, produced through Fred Ladd’s usual NYC Titan Production Co. team (Hols was voiced by Billie Lou Watt; Grunwald by Ray Owens) was of theatrical quality.

The second of these was Tōei Dōga’s Taiyō no Ōji: Horusu no Daibōken (The Sun Prince – Hols’ Great Adventure); 82 minutes, released on July 21, 1968 in Japan, and by American International Pictures Television as The Little Norse Prince in 1970. Was it originally prepared for a theatrical release? The MGM theatrical logo in front of AIP’s, and the quality of the American dub, produced through Fred Ladd’s usual NYC Titan Production Co. team (Hols was voiced by Billie Lou Watt; Grunwald by Ray Owens) was of theatrical quality.

Taiyō no Ōji: Horusu no Daibōken always did have a troubled production history. It was the animators’ feature, not that of Tōei Dōga’s management. It was made during the height of labor unrest at Tōei Dōga. Director Isao Takahata (who was also the studio’s animators’ union chief), supervising animator Yasuo Ōtsuka, character designer Yasuji Mori, key animator Hayao Miyazaki, and others all sided with the animators. Their goal was to make a feature that did not look like a Disney production or Tōei Dōga’s typical children’s cartoons (for example, Jack and the Witch or Fables from Hans Christian Anderson). It was a “democratic” production, with consultation among all the staff and everyone welcome to contribute ideas. The original production schedule was eight months, but thanks to the participation of “everybody”, it was over three years in production. Even then, due to budget cuts it was released unfinished; some scenes such as battles that would have required the most animation were shown as a quick succession of dramatic still shots. But Tōei’s management controlled the distribution. Horusu no Daibōken played for only ten days. As a result, it was the lowest-earning of any Tōei Dōga features, which management used as an excuse to blame Takahata for its “failure”. But it was and has remained a popular favorite. In January 2001, the Japanese Animage magazine voted Horusu no Daibōken the third best anime production of all time.

The setting is the Scandinavian far north in the distant past. (Reportedly it was originally written by Kazuo Fukazawa as a tale of Japan’s northern Ainu natives, but management insisted on changing the setting to Iron Age Scandinavia to make it more internationally saleable. It certainly does not look very “Viking”.) Something is destroying the isolated villages one by one. Hols, a young adolescent, is introduced fighting a pack of fierce “silver wolves”. The fight awakens Mogue (Rockor, in the English dub), a stone giant. Mogue complains of a pain in his shoulder, which Hols discovers is caused by a rusty, dull ancient sword that he pulls out. Mogue recognizes it as the Sword of the Sun, and predicts that when Hols succeeds in reforging it, he will become the Prince of the Sun.

The setting is the Scandinavian far north in the distant past. (Reportedly it was originally written by Kazuo Fukazawa as a tale of Japan’s northern Ainu natives, but management insisted on changing the setting to Iron Age Scandinavia to make it more internationally saleable. It certainly does not look very “Viking”.) Something is destroying the isolated villages one by one. Hols, a young adolescent, is introduced fighting a pack of fierce “silver wolves”. The fight awakens Mogue (Rockor, in the English dub), a stone giant. Mogue complains of a pain in his shoulder, which Hols discovers is caused by a rusty, dull ancient sword that he pulls out. Mogue recognizes it as the Sword of the Sun, and predicts that when Hols succeeds in reforging it, he will become the Prince of the Sun.

Hols lives alone with his father. When the latter is on his deathbed, he reveals that they are the only survivors of a far northern village destroyed by Grunwald, a demonic evil frost king. Hols’ father asks him to return to the far north and defeat Grunwald. Hols and his pet bear cub Koro sail north, where they are confronted by Grunwald who orders Hols to become his ward. Hols refuses, and Grunwald tries to kill him.

Hols and Koro are taken in by a small fishing village, which is being starved out by a giant pike that is eating all the fish. Hols is helped by old Ganko, the village blacksmith. He kills the pike, which was sent by Grunwald, and the fish return. Hols quickly becomes very popular among the villagers, except for the chief, who is jealous of how Hols has become more popular than he is, and the chief’s deputy Drago, who accuses Hols of deliberately overshadowing the chief. Grunwald next sends his silver wolves to attack the village. Hols follows the wolves to a nearby deserted village, where he finds Hilda, a mysterious beautiful girl living alone except for Hiro, her squirrel and Toto, her snowy owl. Hols brings her back to the fishing village, where she soon charms all the villagers even more than Hols has – dangerously so, since most of them drop their work to listen to Hilda’s beautiful singing.

Hilda is really Grunwald’s younger sister, sent by Grunwald to turn the villagers against Hols, since Drago, Grunwald’s spy, is not succeeding in doing this. She believes that she is inhuman, only living due to wearing Grunwald’s Medal of Life that gives her immortality. Toto and Hiro represent her good and evil natures, Toto arguing for her to obey Grunwald for his continued gift of immortality, and Hiro arguing in favor of human friendship and kindness. Hilda at first follows Grunwald’s orders, but she is gradually influenced by the villagers’ friendship. She brings a plague of rats, despite her own misgivings, and Drago finishes off Hols by trying to murder the chief and blame Hols for the attack. Hols vows to leave the village until he can prove his innocence. While he is gone, Hilda reveals her true nature to him by trapping Hols in an enchanted Lost Forest; and Grunwald attacks the village directly with an army of silver wolves and an ice mammoth.

Hols escapes from Hilda’s Lost Forest trap and returns to help the villagers fight the wolves and ice mammoth. Hilda, who has grown increasingly reluctant to help Grunwald, tries to save the village’s children with the Medal of Life. Hols realizes that Grunwald can only be defeated with the Sword of the Sun, which he and Ganko have been working on in their spare time, and he rushes to finish reforging it. This brings Mogue, the stone giant. Together Hols, Mogue, and the villagers kill Grunwald. Hilda discovers that she does not need the Medal of Life to remain alive, and she is welcomed into the village.

Hols escapes from Hilda’s Lost Forest trap and returns to help the villagers fight the wolves and ice mammoth. Hilda, who has grown increasingly reluctant to help Grunwald, tries to save the village’s children with the Medal of Life. Hols realizes that Grunwald can only be defeated with the Sword of the Sun, which he and Ganko have been working on in their spare time, and he rushes to finish reforging it. This brings Mogue, the stone giant. Together Hols, Mogue, and the villagers kill Grunwald. Hilda discovers that she does not need the Medal of Life to remain alive, and she is welcomed into the village.

The Little Norse Prince shows the animators’ intent to make a children’s cartoon that did not look like a simplistic children’s cartoon (Hilda’s character was unusually complex), and that would attract an adult audience. It begins before the title or opening credits with an extended fight scene between Hols and the silver wolves, without any dialogue. The character art design varies between the cuteness of the animal companions, the “normality” of the human characters, and the abstract angularity of Grunwald and the ice mammoth. It is constantly fast-moving. The squirrel and the owl present a powerful moral battle despite their cuteness. The background music is dramatic, and Hilda’s captivating singing is genuinely of high quality. The appearance and characterization of Hilda forecasts Hayao Miyazaki’s later self-reliant female leads. Despite this, it was shown on American TV as a typical kiddie feature. The Little Norse Prince was syndicated to TV by American International Pictures during the 1970s, and shown on the Turner Broadcasting System (TBS) during the early 1980s. Since then it has been generally unavailable in America, although it can be found (the weblink here is to DailyMotion), and it is on DVD in the United Kingdom and France.

Next Week: The saga of Tōei Dōga’s third feature, Animal Treasure Island.

Fred Patten (1940-2018) was an internationally respected comics and animation historian. He has written about anime or comic books for publications ranging from Animation Magazine and Alter Ego to Starlog. He was a contributor to The Animated Movie Guide (2005), and is author of Watching Anime, Reading Manga (2004, Stone Bridge Press), a collection of his best essays, and Funny Animals and More (2014, Theme Park Press), based upon his early columns here on Cartoon Research. He passed away on November 12th, 2018.

Fred Patten (1940-2018) was an internationally respected comics and animation historian. He has written about anime or comic books for publications ranging from Animation Magazine and Alter Ego to Starlog. He was a contributor to The Animated Movie Guide (2005), and is author of Watching Anime, Reading Manga (2004, Stone Bridge Press), a collection of his best essays, and Funny Animals and More (2014, Theme Park Press), based upon his early columns here on Cartoon Research. He passed away on November 12th, 2018.

It seemed like even in regards to the earliest features, there wasn’t that much of a change content-wise. They were all heavily regional films that relied a lot on Japanese or Asiatic folklore, very little of which ever really clicked with American audiences until recently. Americans still tended to favor Roman/Medieval/Victorian fantasies or Arabian-oriented fables rooted in 1001 Arabian Nights lore. Even into the 70s, American interest in Asian folklore was limited to the samurai and kung-fu action craze. It’s no surprise that AIP’s attempt to localize Saiyūki involves changing it to “Alakazam” and rewriting a plot involving royal kingdoms and evil wizards. Obviously that ruse didn’t wash with the public.

A shame, because films like The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon could have gone a long way in stoking American interest in Japanese/Asian fantasy. However, as great as that film is, it might have also suffered from being too foreign in for Western audiences to do well.

It’s kinda strange how The Little Norse Prince is often referred to and marketed as a Studio Ghibli film. Sure Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata worked on it, but it seems a bit like a bait and switch. However, because of this, it is the earliest of these films to get a localized dual language home video release in the West.

Noticed Burger King sponsered local airings of Little Norse Prince and another Toei animated feature in my hometown 40 years ago.

http://vintagetoledotv.squarespace.com/print-ads-wdho/wdho-tv-24-print-ads/13487051

http://www.vintagetoledotv.com/print-ads-wdho/wdho-tv-24-print-ads/13411899

That Dailymotion link redirects to Hulu, where MGM had uploaded the film to some years ago.

http://www.hulu.com/watch/168816

My, what beautiful art they used for the Animal Treasure Island ad!

It’s nice when TV stations bothered to promote these.

http://vintagetoledotv.squarespace.com/print-ads-wdho/wdho-tv-24-print-ads/3475356

Chris,

how are things going with your ink and paint work on your friend’s 16mm cartoon?

Chris,

how are things going with your ink and paint work on your friend’s 16mm cartoon?

It’s been fine (though I paint more than ink since the cels were already xeroxed beforehand). My friend was impressed I could get them done as fast as I could.

What a great post! Very much enjoyed! Much thanks, Fred.

The Little Prince and the Eight Headed Dragon was a film the really blew me away. Its story line was very well written, its designs were innovative, and its backgrounds and animation were masterfully executed. It was unlike anything I had ever seen, and remains one of my favorite animated cartoons.

As good as the art and animation was in The Little Prince and the Eight Headed Dragon, the art and animation in Gulliver’s Travels Beyond the Moon was even better. I feel that Toei was at the top of their game on this film. They achieved a level of quality on this film that they never again matched. True, the story on Gulliver’s Travels Beyond the Moon was more juvenile and not as sophisticated as TLPat8HD’s, but it was well written and entertaining. Gulliver’s Travels Beyond the Moon is my very favorite of all of Toei’s works, and I wish you had delved into it further.

As for The Little Norse Prince, after reading your glowing review of this film I tried to find my copy of it, but I seem to have misplaced it. I will say that I didn’t regard the film as highly as critics and fans seem to regard it. as I recall the production values were pretty low. I seem to recall being especially disappointed with the wolves in the film. their designs were very “un-wolflike”, and their movements were sloppy and jittery, more like television quality anime of the period.

Looking forward to what you’ll have to say about Jack and the Witch, and Madcap Island (a film that I’ve never been able to get my hands on).

No wonder the recent “47 Ronin” flick didn’t work.

I’m pretty certain that it was screened on tv here in Australia as ‘The Doggie Tale of Canterbury’ back in the 70s. I remember reading a description in an old newspaper as ‘Rocky the dog rounds up a group of dogs to fight an evil tiger’ (or something like that).

The trailer subtitles identify the film as “The Little Norse Prince Valiant”; I’ve seen print references as well. Was it ever officially titled thus? One would think King Features would take legal umbrage since they owned the comic strip “Prince Valiant” (whose hero had acquired a solid Viking background by then).

You would think they would. Either they knew and did not press forward or simply did not know.

More people need to see these films. Their importance too anime history can not be stated enough.

who was the lead character designer on the little prince and the eight headed dragon?

i’m guessing that he was also lead designer on ken the wolf boy (the long torsos and stubby legs being the main giveaway).

Yasuji Mori. He designed most of the characters in Toei Doga films at the time. The Ghibli Blog posted some of his drawings a while back. (http://ghiblicon.blogspot.com/2008/12/yasuji-mori-gallery-1.html)

“who was the lead character designer on the little prince and the eight headed dragon?”

It’s been said to be the work of Yasuji Mori who was credited as an “animation director” on this film. He’s been brought up here a few times in the past such as for the shorts “Kitty’s Graffiti” and “Kitty’s Studio”, and in Brubaker’s review of “Hustle Punch”. It’s often said the look of the characters in Nintendo’s Zelda games of the early 2000’s (notably, “The Wind Waker”) was inspired from “Little Prince & The 8 Headed Dragon” with it’s design aesthetic.

“i’m guessing that he was also lead designer on ken the wolf boy (the long torsos and stubby legs being the main giveaway).

It’s hard to tell, I don’t see his name present on that series personally, though he did do quite a lot of work for Toei up to the early 70’s before moving onto Nippon Animation where he continued serving mostly as a designer/layout artist until his death. Wouldn’t surprise me if the work he did on “Little Prince” rubbed off on others once Toei got into producing TV cartoon shows in the 60’s.

http://www.pelleas.net/mori/

http://www.anido.com/archives/category/feature?lang=en

I just uploaded copies of some of the model sheets used on Ken the Wolf Boy. if you look at the drawings of Ken on the far right of his model sheet you will see a strong resemblance to Yasuji Mori’s style.

I’m no expert on Yasuji Mori, nor do I read Japanese. Would appreciate anyone’s thoughts and input.

http://eeteed.blogspot.com/2014/02/here-are-some_18.html

The MGM logo is in front of AIP’s because MGM owns the AIP films now. The MGM logo wasn’t on 60s prints.