Who doesn’t remember classic cartoons?

Who doesn’t remember classic cartoons?

Warner, Disney, MGM, Columbia, Fleischer, Lantz; name a studio, and your eye recalls the images, your brain the actions and personalities of favorite cartoon characters. From Bugs Bunny’s hat dance with “El Toro” to Donald Duck’s fanny-wagging ballet on the ice, animated images were built to last by their artists and storymen.

Same goes for those animated melodies.

No, really: rewatch a cartoon you’ve seen before, and your ears may well recall the background score before your eyes recall the visuals. Quite a feat for mere accompaniment to be so memorable. You know the tunes of Bugs and the bull, of Donald in winter, almost as if they were written to hold an audience on their own.

And so they were.

In truth, the tunes of these old cartoons are memorable because they were the popular music of the 1920s and before: the drinking songs, the minstrel reels, the cultural memories that filled animators’ lives behind the screen. Lives that we today have lost touch with; for excepting classic cartoons, yesterday’s cultural memories sadly fill today’s memory hole.

In truth, the tunes of these old cartoons are memorable because they were the popular music of the 1920s and before: the drinking songs, the minstrel reels, the cultural memories that filled animators’ lives behind the screen. Lives that we today have lost touch with; for excepting classic cartoons, yesterday’s cultural memories sadly fill today’s memory hole.

It’s time to reclaim the past. Cartoon music holds a history waiting for us to rediscover, love, hate, and learn from, and that’s the goal of this page. Starting with classic songs as we know them from cartoons and cartoon spin-offs, I’ll move outward to show you the buried history that they contain: broader cultural significance as seen through vintage sheet music, rare original recordings, bizarre facts and weird old-time cliches. Lots of weird old-time cliches.

Steamboat Willie and Steamboat Bill

Steamboat Willie and Steamboat Bill

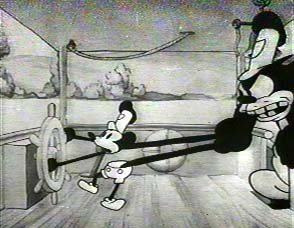

Steamboat Willie (1928) is typically remembered for being what it isn’t: the first Mickey Mouse cartoon (Plane Crazy was made earlier) and the first sound cartoon (Max Fleischer made some sound cartoons in 1924). Willie does have one thing making it a hit, though: that great scene of Mickey piloting the ship and whistling a tune.

Mickey’s tune, Steamboat Bill (1910), had been a hit, too—and not by accident. Song authors Ren. Shields and the Leighton Bros. appear to have banked on success by basing Bill on an earlier song hit, Casey Jones (1909). Jones told of a real-life train engineer’s 1906 effort at a speed record, his collision with another train, and his resultant death. Bill‘s Steamboat Bill seems to be a fictional character; but like Casey (particularly the Casey of the song), he makes bold vows of speed to a long-suffering helper, ends his tragic journey in the Promised Land, and is survived by a wife and children who, though saddened by his demise, are more than ready to move on.

It’s hard for us to imagine how amazing motorized transportation seemed to people a century ago, but Steamboat Bill tries to tell us. Folk were fascinated by trains, steamships, cars, and planes, and at a time when the vehicles were not yet very comfortable or safe, they still possessed the abilities to move speedily and to travel in a new way. People like Steamboat Bill wanted to explore the limits of these powers. When Bill’s ship blows up, hurling him into the air, he still can’t stop living for the challenge, placing a bet from midair on how high he’ll fly.

It’s hard for us to imagine how amazing motorized transportation seemed to people a century ago, but Steamboat Bill tries to tell us. Folk were fascinated by trains, steamships, cars, and planes, and at a time when the vehicles were not yet very comfortable or safe, they still possessed the abilities to move speedily and to travel in a new way. People like Steamboat Bill wanted to explore the limits of these powers. When Bill’s ship blows up, hurling him into the air, he still can’t stop living for the challenge, placing a bet from midair on how high he’ll fly.

That such a fanatic should end up in Heaven is interesting. In spite of Bill’s mania, the song’s audience is supposed to identify with him and see him as a hero. It was likely much easier in a day and age when more people shared his fascinations.

Steamboat Bill the song survived for many years, albeit in corrupted form. The present author has seen later versions that confuse the song’s lyrics and even melody with Casey Jones. Recollections also often stumble over Bill’s “[bank]roll that surely was a bear”—calling something a bear once meant that it was impressive—and mix up the name of Bill’s rival ship, called Robert E. Lee after a Confederate general in the Civil War. The South, stage of powerful plantations in slave days, was also the classical home of the paddle wheeler.

Daffy Duck and Oh! Mister Gallagher and Mister Shean

Daffy Duck and Oh! Mister Gallagher and Mister Shean

Most Americans are, or have been, Looney Tunes fans. Almost all of us have grown up with Bugs, Daffy, and Porky. Many of us also grew up with Capitol Records’ Looney Tunes children’s records. The records, a mix of stories and songs, were produced beginning in the 1940s and, in some cases, remained available on LPs or tapes until the 1980s. Songs associated with their respective characters for years, like I Taut I Taw a Puddy Tat and My Name Ain’t Yosemite Sam, originated with Capitol.

Most Americans are, or have been, Looney Tunes fans. Almost all of us have grown up with Bugs, Daffy, and Porky. Many of us also grew up with Capitol Records’ Looney Tunes children’s records. The records, a mix of stories and songs, were produced beginning in the 1940s and, in some cases, remained available on LPs or tapes until the 1980s. Songs associated with their respective characters for years, like I Taut I Taw a Puddy Tat and My Name Ain’t Yosemite Sam, originated with Capitol.

Not all the Capitol songs originated with Capitol, though. Little did we listeners realize as kids, some looney lyrics were versions of much earlier pop hits. A good example comes in Daffy Duck’s Feathered Friend (1951), wherein Daffy proposes to Elmer Fudd that the two become performers. The song that follows, Oh! Daffy Duck, is adapted from a chart-topper of 1922: Oh! Mister Gallagher and Mister Shean.

Shean, originally written and performed by real-life comic namesakes Ed Gallagher and Al Shean, depicts a pair of characters not unlike postwar Warner protagonists. In successive verses, naive Mr. Shean confronts smart-alecky Gallagher with a series of conundrums, generally coming off the worse for it but occasionally pulling an unexpected fast one.

If nothing else, the Shean song shows that the classic comedy pair of wise guy and patsy endures forever. From 1885’s Tambo and Bones through to Laurel and Hardy, the Fox and the Crow, and Ren and Stimpy, humanity never tires of seeing a naif and a (relatively) smarter guy have at it.

On the other hand, humanity seems to have forgotten Mister Gallagher and Mister Shean. Surprising, given its former renown; for years the song was a Groucho Marx standard, with Jackie Gleason also contributing in one version. Then again, maybe one can understand why the song faded away after all. Its original references to lawn tennis, “living European”, and patently pre-1960s sexual mores mean that while the melody stays catchy, the lyrics are Gilded Age.

Just the same, though, one can’t deny the humor and strangely addictive quality of the song, no doubt why it survived as long as it did. Listen a few times – especially to one of the 1922 recordings – and feel that deceptively simple tune bore its way into your head. For good. You’re never going to get rid of it… heh, heh.

Herr Meets Hare and San Antonio

Herr Meets Hare and San Antonio

From 1936 well into the 1950s, Warner staff musician Carl Stalling assembled wry, wacky, and wholly delicious scores for the studio’s legendary Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies. The scores featured original tunes and classics used in two ways: first to aurally enhance the action with atmosphere, and second – a little more subtly – to comment on the action by means of a song’s name or subject matter. Since Stalling’s song choices have fallen out of public memory today, this particular skill of his often goes sadly unappreciated.

From 1936 well into the 1950s, Warner staff musician Carl Stalling assembled wry, wacky, and wholly delicious scores for the studio’s legendary Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies. The scores featured original tunes and classics used in two ways: first to aurally enhance the action with atmosphere, and second – a little more subtly – to comment on the action by means of a song’s name or subject matter. Since Stalling’s song choices have fallen out of public memory today, this particular skill of his often goes sadly unappreciated.

Herr Meets Hare (1945) is a World War II cartoon. Bugs Bunny, headed for Las Vegas, takes a wrong turn at Albuquerque and lands in Germany’s Black Forest. When he’s hunted by Nazi field marshall Hermann Goering, Bugs pretends it’s Goering who’d wanted to go to Vegas. So what’s the scenes’ sprightly background score got to do with the price of potatoes?

The song is San Antonio (1907), a forgotten hit by Harry Williams and Egbert Van Alstyne. It tells how a bronco buster’s girl has fooled him, absconding with his belongings and running off with another man. As applied to Herr Meets Hare, the song takes on a typically Carl Stalling double meaning. The Wild West theme and sound underline the references to desert towns Albuquerque and Las Vegas, while the lyrics remind us that Goering is being played for a sucker.

Williams and Van Alstyne wrote more than one Wild West hit in their day: 1906’s Cheyenne (Shy Ann) was also theirs. Beginning with Porky’s Phoney Express (1937), Carl Stalling frequently used Cheyenne, San Antonio, and Charley O’Donnell’s My Pony Boy as Texas anthems, invoking them when a cartoon cowboy chase—or hoodwink—was going on.

Before we leave San Antonio, it’s interesting to look at its place in pop music evolution. Though a cheerful-sounding song, it details a tragic scenario that, two generations later, would much more likely have been applied to a slow, sad or at least more obviously romantic country-western melody. In 1907, though, Boot Hill was not far in the past. The rapid pace and speed of San Antonio suggests the minstrel songs that were actually more popular with cowboys themselves. It’s a cheerful tune that just happens to have gloom-ridden lyrics.

Giddap, pardner!

Halloween and Smarty, Smarty, Smarty

Halloween and Smarty, Smarty, Smarty

“Toby the Pup” goes to show that for cartoon characters, survival is a relative thing. In America, this vintage 1930s series from RKO and Charles Mintz became so scarce that, until a couple of years ago, historians largely believed most of the films to have been lost. All of this time in Europe, however, some were still being aired as TV fillers and interstitials – which just goes to show that researchers can always stand to communicate a little better!

“Toby the Pup” goes to show that for cartoon characters, survival is a relative thing. In America, this vintage 1930s series from RKO and Charles Mintz became so scarce that, until a couple of years ago, historians largely believed most of the films to have been lost. All of this time in Europe, however, some were still being aired as TV fillers and interstitials – which just goes to show that researchers can always stand to communicate a little better!

Halloween (1930), a classic Toby cartoon, is highlighted by another moment you just know has a greater meaning. When Toby’s amorous smooching and obnoxious antics send girls fleeing from Tessie’s party, Tessie smacks him down and reprimands him in song.

The song, Smarty by Jack Norworth and Albert Von Tilzer, proves that some things in life never change. As children, we all have to deal with tattletales—those pesky, often younger kids who constantly bawl others out to authority figures. In Smarty, a little girl turns tattletale on seeing her boyfriend kiss another lass. It doesn’t sound very good for the relationship when she threatens to tell his teacher and mother.

A kiss as the subject of controversy gives the song its place in history. It seems about right that in pre-sexual-revolution 1909, a consensual kiss for grade school children should be something to shout about. On the other hand, the last ten years have seen kindergarteners expelled from certain schools on the same grounds, so perhaps we’re reverting again to pruder times?

Though Smarty as a song doesn’t seem to have come down to us today, some traces of it have survived. Comic strips popularized the expression “smarty, smarty, thought you had a party” (and variants thereof); the simple taunts of “smarty, smarty” and “smartypants” (derived from the song’s “smarty cat”) plague their young victims on schoolgrounds to this day.

Classic cartoons and The Darktown Strutters’ Ball

Classic cartoons and The Darktown Strutters’ Ball

Primordial pop culture embraced racial stereotyping: it’s an unavoidable fact. And as early as 1907, cartoons reflected the general trend: J. Stuart Blackton’s short Lightning Sketches concludes with the animator’s hand drawing unflattering images of a “Cohen” (Jew) and “coon” (offensive term for a Black man). This is not, of course, to call Blackton an intentional racist. For all we know, he treated real-life Jews and African-Americans as equals. But like many cartoon makers who followed him, he casually passed along some of the caricatured images that, today, we view as having contributed to oppression.

Caricatured images were also riding high in popular music. The Darktown Strutters’ Ball, a 1917 hit written by Shelton Brooks, presents the “Black dandy” stereotype: Black men and women who dress up slick for big-city soirees, but reveal some kind of bumpkin inner nature by speaking ungrammatically or behaving outrageously. The message – for bigots – was that an African-American trying to be as respectable as a white man was doomed to come in second-best.

Caricatured images were also riding high in popular music. The Darktown Strutters’ Ball, a 1917 hit written by Shelton Brooks, presents the “Black dandy” stereotype: Black men and women who dress up slick for big-city soirees, but reveal some kind of bumpkin inner nature by speaking ungrammatically or behaving outrageously. The message – for bigots – was that an African-American trying to be as respectable as a white man was doomed to come in second-best.

The consequences of such a loaded image, as with all cliches, are felt on several levels. As originally created by whites, the “Black dandy” is a blatantly oppressive concept. But some early 20th century African-Americans used the image in their own pop culture creations; does this make them racists, too? Then there’s the fact that some savvy mediamakers using the “Black dandy” – and other stereotypes of racial minorities acting outrages – interpreted the stereotypes less to say that minorities were ill-behaved than to say white folks were too strait-laced.

The consequences of such a loaded image, as with all cliches, are felt on several levels. As originally created by whites, the “Black dandy” is a blatantly oppressive concept. But some early 20th century African-Americans used the image in their own pop culture creations; does this make them racists, too? Then there’s the fact that some savvy mediamakers using the “Black dandy” – and other stereotypes of racial minorities acting outrages – interpreted the stereotypes less to say that minorities were ill-behaved than to say white folks were too strait-laced.

Both interpretations of a stereotype are seen when 1930s cartoons invoke The Darktown Strutters’ Ball. There’s the blatantly prejudiced interpretation: Trader Mickey (a cartoon no longer seen on TV) uses Strutters to score a wild African village dance, complete with fat native chief. But the Scrappy short Showing Off makes a less prejudiced point. When Scrappy, a white boy, wants attention from Margie, he dances the slickest way he knows – a crude white imitation of Black style. Margie, representing The Man, yawns and ignores it. The point is that we’re supposed to identify with the character who digs what he thinks Black culture is like—and dis the whiter-than-white ice queen who just doesn’t understand. While still some distance from a real acceptance of Black contributions or acknowledgement of white racism, Showing Off is at least an interesting start.

See and hear Scrappy perform The Darktown Strutters Ball in Showing Off. See the 1917 sheet music to The Darktown Strutters Ball (original cover, later version of the cover, Page 1, Page 2).

Hear Arthur Collins and Byron Harlan sing a vintage 1918 recording of The Darktown Strutters Ball.

Hear Lieut. Jim Europes Infantry Band, an early African-American recording group, play a 1919 instrumental recording of The Darktown Strutters Ball.

David Gerstein is a historian, writer, editor, and graphic designer. His books include Mickey and the Gang (the Disney Good Housekeeping pages), Nine Lives To Live (Felix the Cat) and the Floyd Gottfredson Library (Mickey Mouse comic strips). He is currently an editor of Disney Comics for IDW.

David Gerstein is a historian, writer, editor, and graphic designer. His books include Mickey and the Gang (the Disney Good Housekeeping pages), Nine Lives To Live (Felix the Cat) and the Floyd Gottfredson Library (Mickey Mouse comic strips). He is currently an editor of Disney Comics for IDW.

“…for years the song (Mister Gallagher and Mister Shean) was a Groucho Marx standard…”

This is because Al Shean was the Marx Brothers’ uncle. The family name was Schoenberg. Al’s sister Minnie was the Marx Brothers’ mom.

Scrappy is imitating famous vaudeville dancer Joe Frisco. You may be reading too much into that cartoon. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WlZaoL3P3f8 and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AgXLrmUjcj0.

Well, I guess I have to state the obvious, but when I hear “Casey Jones”, I immediately think of those classic animated commercials for GOOD ‘N’ PLENTY candy.

One other oddly related example of what this post refers to might be found in the classic MGM Bosko “trilogy” of cartoons in which Bosko is sent to take treats to his Grandma, a bag of cookies, and he is often stopped by these ravenously hungry, jazz playin’ and singin’ bullfrogs. The song they sing in all three cartoons, “Gramma’s Cookies” has a slight resemblance to the song that appears in a classic Max Fleischer color classic, “KIDS IN THE SHOE”. I believe the song is called “Mama Don’t Allow”.

The whole of all three cartoons centers on the chases, as the frogs run after Bosko, trying to corner him and take his little bag of cookies, singing the song all the while and not missing a beat as Bosko slips past their grasp, but in some ways, musically, the songs do sound alike. I guess that this series of chords were used in many such tunes.

One thing I noticed recently is that one of the old-time songs Stalling used in some train scenes was “On the 5:15“, which I’m surprised I don’t remember the Max Fleischer studio using in any of their early 1930s cartoons, since it was written and performed in 1915 by Billy Murray, whose voice is all over the early Fleischer cartoons (the lyrics themselves almost cry out for some Screen Song animation to go with it, and the baritone sounds a lot like another Fliescher voice-man, William Pennell).

Which Looney Tunes cartoons do “My Pony Boy” play in? I don’t recognize it.

“My Pony Boy” is used in the Porky Pig Looney Tune The Village Smithy (1936)

Carl Stalling developed his skill to score pictures by playing theatre organ as did Oliver Wallace who scored for Disney for decades.