Argentine (or Argentinian) feature animation has been in the news currently, with the theatrical release (maybe) by the Weinstein Company of the Argentine 2013 CGI-animated sports-fantasy Metegol under the title Underdogs. According to Wikipedia, “The film is an Argentine production, and was released in Argentina on 18 July 2013, setting an all-time record for an Argentine film opening at the box-office. Costing $21 million, the film is the most expensive Argentine film of all time, and the most expensive Latin American animated feature ever.” The feature was announced in Argentina on November 27, 2009; released on July 18, 2013; acquired for American release by the Weinstein Company in March 2014; and announced to be released on August 27, 2014. But the American release keeps being pushed back, first to January 16, 2015, then April 10, then August 14, 2015 – and now it’s postponed again to an unannounced date either at the end of this year or the beginning of 2016. This has kept the film in the news and its trailer in the theaters.

The plot is that a lower-class residential neighborhood, the home of Amadeo (renamed Jake in the American dub), the teenage protagonist and his friends, is bought up by an arrogant soccer star to be demolished for a super-sports stadium. Amadeo/Jake is a soccer fan and an expert player of the soccer arcade game known as Metegol in Argentina and as Foosball in America, but he is no athlete. When Grosso/Ace, the soccer star, contemptuously challenges Jake to put together a team of his friends and play Ace’s real soccer team for the fate of his neighborhood, Jake’s Foosball team comes to life and, led by its captain Capi, helps him to win.

The plot is that a lower-class residential neighborhood, the home of Amadeo (renamed Jake in the American dub), the teenage protagonist and his friends, is bought up by an arrogant soccer star to be demolished for a super-sports stadium. Amadeo/Jake is a soccer fan and an expert player of the soccer arcade game known as Metegol in Argentina and as Foosball in America, but he is no athlete. When Grosso/Ace, the soccer star, contemptuously challenges Jake to put together a team of his friends and play Ace’s real soccer team for the fate of his neighborhood, Jake’s Foosball team comes to life and, led by its captain Capi, helps him to win.

Metegol/Underdogs has been a major hit throughout Latin America (where soccer is much more popular than is American football). In Argentina it outgrossed the Argentine releases of Despicable Me 2 and Monsters University. It has already been released in Great Britain under the title The Unbeatables. The animation industry is waiting to see how well it (and a family fantasy about soccer) does in America.

Metegol/Underdogs is not the first Argentine animated feature to become newsworthy in America. In March 2014, the 2007 Argentine hand-drawn animated feature El Arca De Noe was released (after an extremely limited theatrical run) on DVD by Shout! Factory as Noah’s Ark. The film, a definite theatrical adult comedy in Argentina (the talking animals aboard the Ark establish a risqué night club below decks; a horny porcupine tries to rape a pineapple), was packaged by The Shout! Factory to look like a typical children’s Bible story DVD, resulting in outraged complaints from religiously-conservative parents and grandparents who bought it for young children or grandchildren.

Metegol/Underdogs is not the first Argentine animated feature to become newsworthy in America. In March 2014, the 2007 Argentine hand-drawn animated feature El Arca De Noe was released (after an extremely limited theatrical run) on DVD by Shout! Factory as Noah’s Ark. The film, a definite theatrical adult comedy in Argentina (the talking animals aboard the Ark establish a risqué night club below decks; a horny porcupine tries to rape a pineapple), was packaged by The Shout! Factory to look like a typical children’s Bible story DVD, resulting in outraged complaints from religiously-conservative parents and grandparents who bought it for young children or grandchildren.

And, of course, the Disney claim that its 1937 Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was the world’s first animated feature has been drawing challenges for years from animation scholars who point to the Argentine 1917 70-minute El Apóstol. Disney is now usually careful to claim that Snow White was either the first cel-animated, the first color, the first musical – or simply the first Disney – animated feature.

So what animated features has Argentina produced? Actually, the number is in doubt due to all of the international co-productions. A given movie may be claimed as both Argentine and of another country since studios of both nations collaborated on its production. There are Argentine-Mexican and Argentine-Chilean-Uruguayan co-productions. El Ratón Pérez (2006) is undoubtedly Argentine; El Ratón Pérez 2 is an Argentine-Spanish co-production that is usually listed as primarily Spanish (although it was filmed and is set in Buenos Aires).

Here begins a filmography of animated features that appear to be Argentine-directed or whose primary production has been Argentine-controlled.

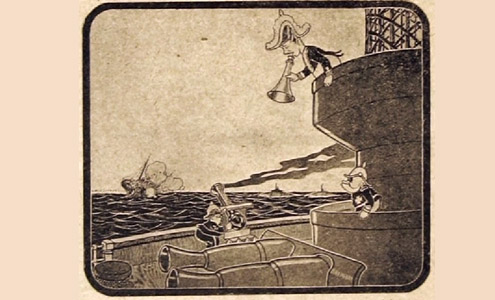

Drawing of President Yrigoyen by Diógenes “El Mono” Taborda for Cristiani’s “The Apostle”

El Apóstol, directed by Quirino Cristiani. 70 minutes. November 9, 1917.

El Apóstol was a political fantasy, lampooning the new administration of President Hipólito Yrigoyen (elected in 1916), who had campaigned vigorously with the promise of ridding Argentine politics of immorality and corruption. In the movie, the unkempt Yrigoyen (nicknamed Peludo (shaggy/idiot) by his opponents) dreams that he dons saintly robes, ascends to Mount Olympus, and takes Jupiter’s thunderbolts to make good on his promises. The resulting rain of thunderbolts on Buenos Aires (a 21’ high plaster model by French sculptor Andres Ducaud) destroys the city.

Contemporary reviews said that the film, written and directed by Quirino Cristiani (1896-1984), was produced in cardboard cutout animation. It totaled 58,000 drawings projected at 14 frames a second. Different sources give both a 60-minute and 70-minute running time. It was well received both critically and by the public, and played for six months; but it was little seen outside of Buenos Aires and was never re-released. Producer Frederico Valle considered that there was little shelf life after 1917 in a topical political cartoon. In 1926 a fire destroyed Valle’s studio and the only prints of El Apóstol.

A rare image from “Sin Dejar Rastros”

Sin Dejar Rastros (Without a Trace), directed by Quirino Cristiani. ? minutes. December 1918?

Cristiani and Valle were handed an ideal opportunity for a second animated political cartoon over the “sin dejar rastros” incident in September 1918. Argentina was neutral during World War I, but the Imperial German embassy in Buenos Aires had established informal friendly relations with the commanders of the Argentine Army. In September 1918 Baron (usually reported in American newspapers as Count) Hellmuth von Luxburg, the German Minister (Ambassador) to Argentina, ordered a German U-boat to sink an Argentine ship “spurlos versenkt” (“without a trace”) so he could blame the Entente powers and hopefully swing Argentina to the German-Austrian side.

The plan failed massively. There were many survivors who agreed that they had been sunk by a torpedo, not a British or French surface warship, and von Luxburg’s secret correspondence was made public. The “spurlos versenkt” phrase became, in Spanish as “sin dejar rastros”, the name for the whole affair. The Argentine government declared von Luxburg persona non grata and he was recalled to Germany in September.

Cristiani and Valle were well aware of Winsor McCay’s The Sinking of the Lusitania, which had just been released in July. They rushed to write and produce Sin Dejar Rastros in Cristiani’s cardboard cutout animation. But President Yrigoyen was trying to downplay the affair to keep Argentina neutral. He ordered the police to confiscate all prints of the film the day after it was released. They disappeared into the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and were never seen again. Sin Dejar Rastros was mostly unseen, and it was never reviewed. It is not even certain that it was of feature length, although it has usually been called a “lost feature” or “the second animated feature ever made” when it is mentioned.

Peludópolis, directed by Quirino Cristiani. 80 minutes. September 18, 1931.

Yrigoyen’s first six-year term ended in 1922, and according to the Argentine Constitution, he could not immediately be re-elected. In 1928 he was overwhelmingly re-elected on his past reputation. But it was soon evident that he was becoming senile now, and it was widely believed that he was being manipulated by corrupt government ministers.

Cristiani, now at his own Estudios Cristiani, started a new animated feature political cartoon, playing on Yrigoyen’s nickname, with Yrigoyen as El Peludo, a pirate who overthrows Captain Pelado (Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear, Argentina’s 1922-1928 president), renames his ship the Peludópolis (Peludo City; a metaphor for Argentina), and sets out surrounded by hungry sharks (Yrigoyen’s Radical Party corrupt ministers) in a new direction toward the island of “Quesolandia”.

How the movie was originally intended to end is unknown. The Great Depression ruined the Argentine economy; Yrigoyen was considered too feeble to stop the decline; and on September 6, 1930 he was ousted in a military coup d’etat supported by the Conservative Party. The new president was General José Félix Uriburu. Cristiani was unsure what Uriburu’s new policies would be; and as soon as Yrigoyen became a helpless old man under house arrest, he got the public’s sympathy as having tried to do the best that he could. Cristiani cobbled together a new ending that vaguely supported the military government as sailing up in a paper boat and “saving” Peludópolis, and released it a year later. It was a box-office success, but by the time the elderly Yrigoyen died on July 3, 1933, it was generally felt that the world economy was spiralling downward out of anyone’s control, and too depressing for a satire. Peludópolis was already a dated political cartoon, and Cristiani “respectfully” withdrew it from circulation. The surviving 35 m.m. prints were destroyed in fires in Cristiani’s warehouse in 1957 and 1961, and it is another lost film today.

Part of what made Peludópolis a hit in 1931 was the publicity that it was the first animated sound feature. It was begun as a silent, but Cristiani added music, songs, and some dialogue before its release. The soundtrack was on the Vitaphone sound-on-disc synchronization system, to be played along with the film, rather than an on-film soundtrack.

There were several Argentine animated shorts in the next three decades, including some by Cristiani. Special note should be made of Argentina’s first color animation, which is often cited by Argentine animation fans with pride: the 12-minute Upa en Apuros (Upa in Trouble), released on November 20, 1942 at Buenos Aires’ Ambassador Theater, immediately following the Argentine premiere there of Disney’s Saludos Amigos (then titled only Saludos), along with the live-action feature La Guerra Gaucha (“The Gaucho War”, about the 1817 gauchos of Saltilla province’s guerrilla war against the local royal Spanish army for Argentina’s independence).

Upa in Trouble was directed by Tito Davison, but it was written by and featured the characters of cartoonist Dante Quinterno’s extremely popular Patoruzú weekly comic strip magazine (Upa is Patoruzú’s younger brother, who is kidnapped by Juaniyo the gypsy), and produced at Quinterno’s magazine-cartoon studio. Quinterno had briefly been employed by the Disney studio during a trip to the U.S. in 1933.

Upa in Trouble was directed by Tito Davison, but it was written by and featured the characters of cartoonist Dante Quinterno’s extremely popular Patoruzú weekly comic strip magazine (Upa is Patoruzú’s younger brother, who is kidnapped by Juaniyo the gypsy), and produced at Quinterno’s magazine-cartoon studio. Quinterno had briefly been employed by the Disney studio during a trip to the U.S. in 1933.

J. B. Kaufman’s South of the Border With Disney says that Walt Disney’s “El Grupo” tour “researched prominent [South American] artists. Among those investigated was Dante Quinterno, whose comic character Patoruzú was then a popular favorite in Argentina.” (p. 24) When the Disney tour visited Buenos Aires in September 1941 and set up a temporary studio in a hotel, “Dante Quinterno, creator of the popular Argentine comic strip character Patoruzú, visited one day to discuss a two-reel animated cartoon he was producing,” (p. 46); and Disney publicly praised the animated cartoon when it was released.

It is obvious from the quality of Upa en Apuros that Quinterno studied Disney’s animation closely. Quinterno, rather than Davison, was given a Special Award for Upa en Apuros being the first Argentine color animated cartoon, at the 1943 Argentine Film Critics Association’s presentation of their Premios Cóndor de Plata.

By 1942 Quinterno’s Patoruzú was starring in his own super-popular weekly cartoon magazine, and all Argentinians and Uruguayans were familiar with him and his supporting characters. Roughly, Patoruzú was an equivalent of Popeye; the super-strong but naïve cacique (chieftain) of Patagonia’s Telhuelche natives. Upa was his even more hapless younger brother; and Juaniyo the evil gypsy was a recurring villain, the equivalent of Popeye’s Bluto. Quinterno’s characters would reappear in Argentine animated features in the 2000s.

But after 1931, it was another 32 years until anyone in Argentina made another animated feature.

Comahue, directed by Edgardo Togni. 61 minutes. 1963.

Comahue was an animated documentary, produced in black-&-white, in 1963. It featured animation by Manuel García Ferré and was essentially a travelogue of Argentina’s southern provinces, the country’s largest fruit growing area. It was apparently only screened in a special exhibition at The Opera Theatre in Viedma and in Neuquén on September 30th 1963. Beyond that, little else is known about this film.

Next week: More Argentine Animated Features; and more about García Ferré.

(Special Thanks to Jorge Finkielman)

Fred Patten (1940-2018) was an internationally respected comics and animation historian. He has written about anime or comic books for publications ranging from Animation Magazine and Alter Ego to Starlog. He was a contributor to The Animated Movie Guide (2005), and is author of Watching Anime, Reading Manga (2004, Stone Bridge Press), a collection of his best essays, and Funny Animals and More (2014, Theme Park Press), based upon his early columns here on Cartoon Research. He passed away on November 12th, 2018.

Fred Patten (1940-2018) was an internationally respected comics and animation historian. He has written about anime or comic books for publications ranging from Animation Magazine and Alter Ego to Starlog. He was a contributor to The Animated Movie Guide (2005), and is author of Watching Anime, Reading Manga (2004, Stone Bridge Press), a collection of his best essays, and Funny Animals and More (2014, Theme Park Press), based upon his early columns here on Cartoon Research. He passed away on November 12th, 2018.

Highly recommend this documentary on Quirino Cristiani:

http://www.quirinocristianimovie.com/

Arthur Babitt was consultor in Upa In Trouble (uncredited)

http://babbittblog.com/2012/04/27/the-babbitt-diary-animating-in-argentina-partt1/

Upa en Apuros (Argentine Spanish) or Upa en Problemas is one of the funniest animated Films that I’ve seen from Argentina,with Patoruzú which made him one of the first true superstars in Argentine Animation.

The 2007 Argentine animated “El Arca” was apparently released as “El Arca de Noé” in several Latin American countries, and was made available with a choice of either Spanish Spanish or Argentine Spanish dialogue tracks.

When I learned elementary Spanish in high school, our teacher the first year was an arrogant Castilian who announced that in HIS class, we would learn GENUINE Spanish, not whatever they spoke in Mexico. The Mexicans in the class hated him and accused him of deliberately trying to fail them, which he certainly made believable. About ten years later I discovered a Mexican newsstand that mixed Mexican, Spanish, and a few Chilean comic books together. The Mexican comics were full of Mexican slang that either wasn’t in a Spanish-English dictionary or had a completely different meaning. For example, “charro” was obviously a cowboy like Roy Rogers; the Spanish dictionaries said that a “charro” was a country bumpkin or fool.

And now you understand why this is confusing Fred! (much in the way American English differs wildly from the British mother tongue).

Holy Smokes! I’ve been curious about the 1917 Argentinian feature-length animated film since I read a brief note about it by Mr. Beck in, I think, the Cartoon Brew Web site a few years ago. Now I see there’s quite a bit more to the story. Who’d’a thunk the Argentinians were so far ahead of the rest of the world in full-length animated feature films? Thank you for this fine entry, Mr. Patten!

El Arca was rated ATP (Apta Todo Publico/Suitable for All Audiences) in Argentina and definitely marketed to children. There’s no rape scene that I know of. There is a nearsighted porcupine *kissing* a pineapple but I think not even the Taliban would describe that as a rape scene.

Yes, that’s the scene that I mean. “Rape” was probably putting it too strongly since “El Arca” was a FAMILY film, meant for children as well as adults; but it’s pretty obvious what is implied. The opening of the film is set before the Flood and is supposed to show how libertine civilization has become.

That seems to be a favorite scene with most of the reviewers. It’s interesting to see how often the overly-amorous animal is named a porcupine vs. a hedgehog. There is quite a size difference between a porcupine and a hedgehog in real life, but some reviewers don’t seem to realize that. Also in prickliness — I’ve seen photographs of people holding a hedgehog in one open hand. You wouldn’t try that with a porcupine.

Thanks so much for this post. My family is from Argentina and Chile and I spent a lot of time there as a kid. I grew up with Paturuzu and Hijitus and still have some of their comics. My father actually met Walt Disney during the “El Groupo” tour. He got an autograph…that got misplaced…he was very upset about losing that. Years later on a trip to Argentina he met Molino Campos’ widow, and got a small copy of a photograph with Disney and Molino Campos. When the laserdisc of Saludos Amigos came out, one of the extras was a complete itinerary of the trip. I asked my dad if he remember what day of the week it was when he met Disney…he said it was a Friday…we looked it up..and sure enough, he was in Mendoza on a Friday the date and time that my dad remembered.