MGM’s cartoon unit was humming during this period – including continuing to use tunes from various MGM musicals. The studio’s work continued to display influences from other studios, particularly from Warner Brothers, and cross-pollination within its own ranks, as Tom and Jerry begin to acquire sporadic Avery influence (e.g. Mouse Cleaning). One suspects the exhibitors were well-pleased with the finished results, as were the audiences.

MGM’s cartoon unit was humming during this period – including continuing to use tunes from various MGM musicals. The studio’s work continued to display influences from other studios, particularly from Warner Brothers, and cross-pollination within its own ranks, as Tom and Jerry begin to acquire sporadic Avery influence (e.g. Mouse Cleaning). One suspects the exhibitors were well-pleased with the finished results, as were the audiences.

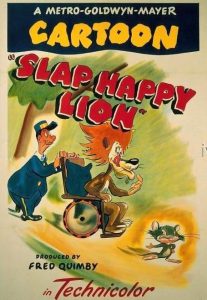

Slaphappy Lion (9/20/47) – A tough-guy mouse is explaining to the audience why a lion is strumming his lips, hitting himself over the head with a mallet, and showing other signs of dementia. It turns out that this lion is mouse-shocked, and goes into hysterics any time he sees a mouse. Back in the jungle, his roar would send all the animals scurrying away in a panic. But he finally meets his match in the form of a mouse who isn’t afraid. The mouse realizes his edge over the lion, and takes full advantage of the situation. The lion is driven berserk by the mouse’s pranks, and repeated utterances of the word “Boo”. As we return to the present, our mouse narrator still can’t quite figure out how anyone could be scared by a mouse. Until the same mouse who spooked the lion shows up, greeting our narrator with a “Boo”, and sending the narrator mouse racing hysterically over the hills. Song: “Blaze Away”, a march written by Abe Holzmann. The Columbia Orchestra recorded a very early disc circa 1901. It was also recorded acoustically by Pietro Diero, accordionist, for Victor. Victor managed to get a real British band (possibly on tour) for an American recording session – Kindle’s 1st Regimental Band. Columbia would issue a replacement for its 1901 version by Prince’s Band. Ray Noble’s New Mayfair Dance Orchestra did an HMV version. Reginald Dixon got an organ issue on Regal Zonophone. The William Hannah (no relation) Trio (2 accordions and a violin) performed it on Parlophone. Eddie Peabody issued a version on British Columbia while touring in Europe. Wingate’s Temperance Prize Band performed a 9″ version on British Crown. Many other versions appeared in England, where the march became much more of a standard than in the States.

Kitty Foiled (6/1/48) – An endless chase and more fast and furious gags, as Jerry and a canary take turns saving each other from the clutches of Tom. They fool Tom into thinking he’s been shot, by Jerry dropping a light bulb while the canary wields a dueling pistol. But Tom finally gets wise, and ties Jerry to the tracks of a model railroad. Tom charges Jerry with the toy locomotive, but the canary mounts an aerial attack, armed with a bag from the closet containing a bowling ball. The projectile is dropped ahead of the train, causing Tom and train to take a dive into the basement for their ultimate downfall. Song: Rossini’s “The Barber of Seville Overture”, recorded by Rudolph Ganz conducting the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra on blue label Victor, the Halle Orchestra conducted by Sir Hamilton Harty on British Columbia, Arturo Toscanini and the Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra of New York on Victor Red Seal, the Comedian Harmonists on Electrola, and the BBC Symphony Orchestra on British Columbia. Also, a return for “My Blue Heaven”, and an unidentified accordion polka, as Jerry and the bird celebrate Tom’s fake demise.

Little ‘Tinker (7/15/48) – B.O. Skink is quite well aware of his olfactory problem. We see him taking a shower using “O Buoy” soap, and pouring a whole bottle of perfume over his head – for all the good it does. When he steps out on his walkway, all the flowers wilt and die. The skunk is visited by Dan Cupid, who has to retreat until he can find himself a gas mask. Cupid provides B.O. with a book on how to find love. B.O. tries several of the techniques illustrated in the book, to no avail. He even tries crooning, in a sequence commented on by many writers, alternating skinny jokes about Frank Sinatra with the swooning reactions of various female fans, who keel over in universal reaction to B.O.‘s “Rhapsody in Pew”. The adoring fans swamp the stage, but the inevitable close-up whiff of B.O. sends them packing. B.O. finally resorts to camouflage, disguising as a fox. He meets up with a female of the species, and they happily pass over a log bridge, but stumble into the water below. B.O.’s disguise melts away – but so do the features of his new girlfriend, revealing a female skunk. The two know a love match when they see one, and B.O. drops the book out of the closing iris, knowing he will have no further need for its advice to the lovelorn. Songs: mostly old favorites, including “Mendelssohn’s Spring Song”, Honey”, and “Wonderful One”. But the new featured number is “All Or Nothing At All”, a dramatic ballad from 1939, recorded at the time by Freddy Martin on Bluebird, Count Basie on Okeh, Jimmy Dorsey on Decca, and most notably, Harry James on red label Columbia, with vocal by Frank Sinatra. The song did not make an instant mark, but was reserviced into use in 1943, about the time Sinatra was swooning the girls as a single artist at the Paramount Theater in New York. The song became a million seller on reissue. Sinatra would record it again in later years for both Capitol and Reprise. Eric Winstone and his Band would cover it for the British isle on HMV.

The Bear and the Hare (6/26/48) – A brilliantly-timed Barney Bear installment, on a parity with contemporary Ton and Jerry’s, with gags coming fast and furious. Barnet takes to skis and snow gear, hunting the elusive snowshoe rabbit, a critter so well camouflaged against winter’s icy blanket that you can’t see anything of him except his eyes and footprints. The creature leads Barney on a frenetic chase up and down narrow slopes, off cliffs, and finally a plummet into a canyon, where Barney has set an encirclement of bear traps in wait for his prey. As Barney takes aim with a rifle, the rabbit in pantomime bids goodbye to the wife he will leave behind, and an offspring, and another, and another, until the screen is filled with images of his very-extended family. Barney takes pity, his heartstrings giving in to sympathy, and tosses the rabbit safely out of the trap encirclement. The rabbit whistles, and makes his point as to how much a sucker Barney’s been, by throwing a snowball in his face. Barney reverts to the bear he is, and with a roar charges the traps, ending the cartoon still in pursuit of the hare, traps clinging to and dragging behind Barney everywhere as he goes. Songs: “Minute Waltz”, by Frederic Chopin. Recordings include an imported Columbia by Ignaz Freedman, Alexander Schmidt on Victor, Jose Iturbi in a Chopin Medley on Red Seal Victor, a concertina version by “Raphael” on Decca (imported). Ray Turner on Capitol, Liberace on Columbia custom, John Kirby (Columbia or Okeh?). Charlie Ventura on Imperial, Gaylord Carter on Black and White, a polka version by Stephen Kovacs on Continental, and Alfred Newman on Majestic.

The Truce Hurts (7/17/48) – No need to cut to the chase, as Tom, Jerry, and Spike are already at it as the cartoon opens, swinging lethal weapons at one another. Finally, the dog decides all this chasing and hitting is getting nobody nowhere, so he proposes a peace treaty. The text of the treaty will be well remembered to fans of Avery’s “Blitz Wolf”, as it is nearly identical in terms to Adolf Wolf’s treaty with the pigs, including clause that the one who breaks it is a stinker. Of course, the truce doesn’t last all that long, when a steak falls off of a butcher’s truck, and each of our trio has a different idea on how to carve it – with cuts favorable to themselves, and white lines drawn upon it like a soccer pitch. Well, it was a nice try while it lasted – back to the chasing and swinging weapons. (Notably, this ending, though better elaborated upon here, is essentially identical to Friz Freleng’s ending for “The Fighting 69th 1/2″) Songs: “Over the Rainbow”, the Oscar winner from “The Wizard of Oz”. Judy got to record it for Decca, and later for Capitol. Glenn Miller covered it for Bluebird. Larry Clinton also recorded it for Victor, with vocal by Bea Wain (below). Ginny Simms performed a vocal with complete verse on Vocalion. Lanny Ross, fresh from “Gulliver’s Travels”, recorded a version on Schirmer Records (a music publishing company from New York, who tried tor a short time to put our their own records.) Jack Hylton covered it for Britain on HMV. Frank Sinatra had a version on Columbia. The Bud Powell Trio issued a jazz take on Blue Note. Errol Garner issued a Regent side. Jo Stafford revived it in 1945 on Capitol. David Rose also waxed it for RCA Victor. Ray McKinley had a band version on Majestic. Homer and Jethro would noodle around with it on King. Maynard Ferguson tried his hand at it on Emarcy, and James Moody on Prestige. Les Brown revived it on Coral. Peggy Mann, a former vocalist for Bob Crosby, recorded a version on red vinyl for Silvertone Record Club. The Echoes (a doo wop group) recorded a good version in such style on Specialty in 1957. Children’s labels would pick up the piece, including a surprisingly “legit” heartfelt vocal by Michael Reed on Peter Pan Records. Mel Carter would revive it as an album cut on Imperial. Michael Feinstein would of course include the tune on the MGM album.

Ol’ Rockin Chair Tom (9/18/48) – Mammy Two Shoes has had enough of screaming in the kitchen from the antics of Jerry. She’s decided Tom is ready for the rocking chair, and hires a new younger cat (an orange tabby named Lightning, who leaves an electrical contrail wherever he runs), who makes short work of Jerry, and equally rapid effort to oust Tom. Tom and Jerry again form one of their uneasy allegiances to rid themselves of the common pest. With the aid of a flat-iron and a magnet, they cause Lightning to swallow the iron, and be dragged around the house by the magnet wherever they choose to place him. Featured in the original version of the soundtrack is one of Mammy Two Shoes’s most iconic lines, delivered in delightful underplay. “Thomas, if you is a mouse catcher, then I is Lana Turner – which I ain’t.” Song: “I’m Sitting On Top of the World” a 1925 pop song written by Lewis, Young, and Henderson. Recorded for Victor in a dance version by Roger Wolf Kahn and his Orchestra, and in a vocal version by Frank Crumit. Columbia gave its dance version to Ross Gorman and his Orchestra. Brunswick gave a dance record to Isham Jones, and issued a best-seller vocal by Al Jolson (below). Jolson would remake the song years later for Decca. Okeh gave it to the Melody Shieks (a San Lanin group), and Lanin also recorded it under his own name for Perfect and Pathe, and for Banner and other associated labels. Vocalion had a vocal record by the Radio Franks (Wright and Bessinger). Wright and Bessinger also recorded vocal versions for Columbia and Edison. Edison also recorded a banjo solo by Harry Reser. In the ‘50’s, Les Paul and Maty Ford had a version on Capitol. Jerry Lewis revived it on his Decca album, “Just Sings”. Norman Brooks issued a sound-alike to the Jolson original on a tribute album for various labels associated with Promenade and Peter Pan Records.

Lucky Ducky (10/9/48) – Dedicated to the intrepid hunter who goes out in the morning with a loaded gun, and comes back in the evening loaded. Two such intrepid canine hunters (much resembling Geouge and Junior, but with no dialogue) are on the lake in a rowboat in the a.m., surrounded everywhere by a flock of ducks – performing a conga dance around the rim of their boat, as a sign prohibits shooting before 8 a.m. A time clock sounds a whistle, and within a matter of a handful of frames, all ducks disappear from the lake to parts unknown. Only one stray duck remains to shoot at – a mother duck passing overhead with a nest strapped to her rear. A gunshot breaks the strap holding the nest, depositing an egg into the hunters’ boat, which begins to hatch while falling. A newborn duckling emerges, removing the shell like a strip-teaser. The fledgling duck, with an irritating Woody Woodpecker-like laugh, seems as resourceful as Tweety at Warner Brothers, leading the hunters on a merry chase, Tex Avery style. Standout gags include a “School Crossing” – taken literally – and a spot where the characters run past a white line on the road, and instantly transform into black-and-white. They walk back to the line, spotting a sign they failed to read in their haste, reading “Technicolor ends here”. The time-clock whistle sounds again, with a sign reading, “No shooting after 5:00 p.m.” All the ducks return, resuming their conga, now joined by the fledgling for the closing – and, in the original release print, further conga dancing by the MGM lion logo. While there are no identifiable songs except repeat performances of “Lovely Lady” for the striptease and the “Light Cavalry Overture” during the chase, an original Scott Bradley conga, title unknown, underscores both the opening and closing sequences.

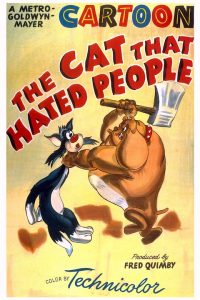

The Cat That Hated People (11/20/48) – A Jimmy Durante -style cat sulks in a cardboard box in a back alley, living by the creed, “People are no darn good.” He illustrates through flashbacks various examples of his horrific life, including swallowing thrown boots while singing on a backyard fence, having paper bags tied to his feet, and even being flung around by the tail by a infant in a playpen. As he lies on a sidewalk, with a constant flow of people walking all over him, he vows that he will find a way to get away from people, even if he has to go clear to the moon. Conveniently, a rocket rental facility presents itself as the building he’s leaning on – advertising service any place in space. Wandering into the place, the cat selects a rocket, presses a starter button amidst a dashboard of a thousand gizmos, and blasts off in a harrowing ride that ricochets his craft like the bumpers of a pinball machine off of various asteroids to the moon’s surface, triggering a sign atop the moon reading “Tilt”. For about ten seconds, everything looks to be the peace and quiet the cat dreamed of – then all heck beaks loose, as the moon’s inhabitants appear – several bearing strong resemblance to the citizens of Bob Clampett’s “Wackyland”. In Avery’s obvious homage to the Clampett original, the cat endures both torture and humiliation – hammered into the ground by a living hammer, then pried up like a nail. Planted in the ground by a live shovel, until he rises from the ground sprouting flowers from his ears – then placed by a living glove into a giant vase. Having his tail carved to a point by a live pencil sharpener, followed by the cat using the point to draw an arrow pointing to himself on a rock, and the word, “Chump.” Eventually, the cat’s had all he can stand, realizing home was never like this. He makes a hasty exit in a style in tune with the weirdness of the lunar world, pulling down from nowhere a backdrop depicting a golf course, and launching himself with a driver off a tee in a clean shot back to planet Earth. He lands on the same sidewalk, to receive the same trampling, but smiles to the camera: “You know, folks, I love people,.”

The Cat That Hated People (11/20/48) – A Jimmy Durante -style cat sulks in a cardboard box in a back alley, living by the creed, “People are no darn good.” He illustrates through flashbacks various examples of his horrific life, including swallowing thrown boots while singing on a backyard fence, having paper bags tied to his feet, and even being flung around by the tail by a infant in a playpen. As he lies on a sidewalk, with a constant flow of people walking all over him, he vows that he will find a way to get away from people, even if he has to go clear to the moon. Conveniently, a rocket rental facility presents itself as the building he’s leaning on – advertising service any place in space. Wandering into the place, the cat selects a rocket, presses a starter button amidst a dashboard of a thousand gizmos, and blasts off in a harrowing ride that ricochets his craft like the bumpers of a pinball machine off of various asteroids to the moon’s surface, triggering a sign atop the moon reading “Tilt”. For about ten seconds, everything looks to be the peace and quiet the cat dreamed of – then all heck beaks loose, as the moon’s inhabitants appear – several bearing strong resemblance to the citizens of Bob Clampett’s “Wackyland”. In Avery’s obvious homage to the Clampett original, the cat endures both torture and humiliation – hammered into the ground by a living hammer, then pried up like a nail. Planted in the ground by a live shovel, until he rises from the ground sprouting flowers from his ears – then placed by a living glove into a giant vase. Having his tail carved to a point by a live pencil sharpener, followed by the cat using the point to draw an arrow pointing to himself on a rock, and the word, “Chump.” Eventually, the cat’s had all he can stand, realizing home was never like this. He makes a hasty exit in a style in tune with the weirdness of the lunar world, pulling down from nowhere a backdrop depicting a golf course, and launching himself with a driver off a tee in a clean shot back to planet Earth. He lands on the same sidewalk, to receive the same trampling, but smiles to the camera: “You know, folks, I love people,.”

Song: “I’m Nobody’s Baby”, played over the credits. The song goes back to 1921. Marion Harrus was among the first to perform it for Columbia. The All Star Trio got a dance version on Victor. The Happy Six (a Harry Yerkes group) also performed for the dance audience on Columbia. Ruth Etting had a 1927 Columbia electrical. Judy Garland gave it an MGM connection by reviving it for a performance in “Andy Hardy Meets Debutante, and waxed a version for Decca. In the wake of the revival, the song achieved new popularity. Benny Goodman issued a red-label Columbia version. Ozzie Nelson did a version on Bluebird (below). Johnny Messner got a Varsity version. Bob Crosby got it for Decca dance version with vocal by Marion Mann. Mildred Bailey also sang it, likely on red Columbia. Tommy Dorsey had the Victor version. Tommy Tucker Time covered it for Okeh. Jack White recorded a British version on Regal Zonophone. Geraldo also got it for Parlophone. Flanagan and Allen got the British Decca version. Joe Loss got am HMV version. Carroll Gibbons followed suit on British Columbia. Frankie Howerd, a comedian who made a few records, issued a 1949 version on British Harmony. Betty Hutton would revive it for Capitol in 1953. Connie Francis did an MGM revival in 1958. Jo Ann Campbell used it as the title cut for an LP release on End. Vic Damone included it on the Capitol LP, “My Baby Loves to Swing”.

NEXT TIME: 1949 and on…

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

Oh how I love these needle drop notes posts. Of course I like MGM cartoons in general! One song you omitted, however; “the truth hurts“, you can hear “off to see the wizard“ as the three, hand-in-hand walk, and dance down the road, only to be cut off and sprayed with mud by a passing truck that drops the steak onto the highway. That of course changes things as you pointed out.THE BEAR AND THE HARE is one of those cartoons that deserves a full and complete restoration. I remember this title as part of the montage of violent cartoon scenes that opened up the early morning cartoon show that I loved to watch before the ABC affiliate newscast in the morning on weekdays and weekends. it is because of this that I finally remember the cartoon. It has those kinds of gags running through the entire cartoon! As you pointed out, it has a wonderful score throughout as well.

“Blaze Away” was a signature tune of Eddie Peabody, “King of the Banjo.” He spent several years in England in the late 1920s and ’30s and did much to promote the instrument in that country. The arrangement of “Blaze Away” played here by Raymonde and His Band of Banjos is very similar to Peabody’s — both are played in the same key of C major, for example — although Peabody typically broke into a ragtime rhythm towards the end. I don’t know who “Raymonde” was, whether he was an actual person or a fictitious figurehead like Sgt. Pepper, but the lead player in the group was B. W. Dykes, later soloist with Troise and his Banjoliers, who had a regular program on the BBC during the war years. Dykes was also a mandolinist, and halfway through “Blaze Away” he swaps his tenor banjo for an 8-stringed one tuned like a mandolin. I’m intrigued by the gigantic bass banjo in the background. Banjos are heavy instruments because of all the metal in them, and that bass must have weighed a ton.

More banjo bands, please!