A Note From Steve Stanchfield: As I’m busy sorting the ‘Thunderbean in Exile’ area that is now occupying the better part of the basement here, my good friend Eric Grayson was kind enough to step in and write a little about Not Wedded But a Wife. Eric is a Film historian, writer and collector. His film restoration projects are top-notch, and he presents films (on film) on a regular basis around the country. Eric also produces (and works with other producers) on Blu-ray sets of rare films.

Take it away, Eric!

A Charley Bowers Cartoon Detective Story by Eric Grayson

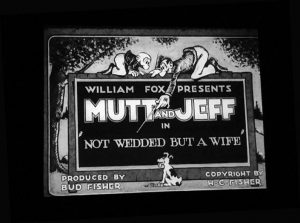

In December of 2018, a friend called me and said he had a nitrate cartoon. It was a Mutt and Jeff cartoon from 1921 called Not Wedded But a Wife. Now, a lot of you reading this will say, “Who cares? I’ve seen a ton of these and they’re not very good!” Well, the cartoons you’ve seen are almost all from the 1925-6 era, when another company was doing them. The earlier ones number at least 200, and they’re represented today by a scant dozen or so survivors.

Why? Well, the earlier ones were almost all distributed by Fox. The negatives would have resided there, and the negatives and all prints blew up in a catastrophic fire in 1937. The remaining prints had almost literally been beaten to death. Fox didn’t keep good control over the prints, and they didn’t actually copyright them (even though they claimed to), so the theater owners just ran cartoons until they wore out. Fox itself regarded these cartoons as a disposable commodity and wanted a new one every two weeks. That’s an output unmatched by most TV production in today’s automated age. As one might expect, the cartoons are rather poorly animated, with slapdash artwork and some weak gags. The 1925-6 cartoons are a lot better, and those aren’t exactly classics.

Why? Well, the earlier ones were almost all distributed by Fox. The negatives would have resided there, and the negatives and all prints blew up in a catastrophic fire in 1937. The remaining prints had almost literally been beaten to death. Fox didn’t keep good control over the prints, and they didn’t actually copyright them (even though they claimed to), so the theater owners just ran cartoons until they wore out. Fox itself regarded these cartoons as a disposable commodity and wanted a new one every two weeks. That’s an output unmatched by most TV production in today’s automated age. As one might expect, the cartoons are rather poorly animated, with slapdash artwork and some weak gags. The 1925-6 cartoons are a lot better, and those aren’t exactly classics.

So why did I care about one of these cartoons? Well, I’m not a cartoon guy particularly. I’m a film guy, and I have a love for stop motion animation. About 25 years ago, people started digging up Charley Bowers films, from Educational and FBO. Serge Bromberg at Lobster Films released a compilation of them on DVD. Bowers’ films are unique. They show a strange worldview that is unlike anything you’ve ever seen. Sort of like Ernie Kovacs meets a Max Fleischer cartoon while on serious drugs. I love them.

So I said, “Well, this belongs in a museum!” This is one of the dumb things I say that gets me in trouble. I spoke to my friend, and he said he didn’t want to donate it, but he’d let me scan it for preservation.

I turned to Serge Bromberg, who, in typical Serge fashion, was traveling in Bolivia or somewhere. I asked Serge if he wanted to finance the restoration and put it out on his upcoming Bowers Blu-ray. If you don’t know Serge, he is the absolute pinnacle of a Frenchman. He’s one of the pillars of the preservation community. He said, “The problem with this is that we never know whether those early Mutt and Jeffs were done by Bowers or someone else.”

I turned to Serge Bromberg, who, in typical Serge fashion, was traveling in Bolivia or somewhere. I asked Serge if he wanted to finance the restoration and put it out on his upcoming Bowers Blu-ray. If you don’t know Serge, he is the absolute pinnacle of a Frenchman. He’s one of the pillars of the preservation community. He said, “The problem with this is that we never know whether those early Mutt and Jeffs were done by Bowers or someone else.”

I thought to myself, “Let’s find out if it really was a Bowers cartoon. How hard can that be?” These are the famous last words that almost always cause me a lot of trouble.

In the meantime, time was nigh for getting a grant to restore the film from NFPF. I decided to strike while the iron was hot, but everyone wanted to know the history of the cartoon. I’m not a 501(c)(3) and I needed the backing of one to get a grant so I could restore the cartoon myself. How hard can that be? Well, that one I knew, since I’ve been doing independent film restorations for several years.

There’s not a lot of information about this in the libraries. I have a friend who is a librarian, with access to all sorts of databases, and he came up with precious little. I scoured archive.org, Media History Digital Library, and the valuable Old Fulton NY Postcards. There was not much out there, and what was out there was often contradictory and confusing.

People will often tell you to trust only primary sources, the things that were published contemporaneously with the events, since in citing later sources, you’re often replicating mistakes that have already been made. I came to realize that with Bowers, even primary sources are unreliable. The man was a consummate con man and BS artist to his very core. It even stretches to his date of birth.

Here is what I’ve been able to piece together and verify, along with some questions I haven’t been able to answer.

Bowers was born in 1877 in Cresco, Iowa. Many sources cite 1887, but I found the census records, and it shows him in the 1880 census. If you search him on ancestry.com, you’ll find official government records that are utterly fabricated, in Bowers’ own handwriting, with differing dates of birth. You just couldn’t trust a thing he said.

There are records of Bowers doing stage work in New York in 1905 or so, and some mentions of him doing stage design. He was also a newspaper cartoonist, which is fairly well documented, so I won’t get into that here.

Bud Fisher started the Mutt and Jeff comic strip in 1907. It became a success and made Fisher rich. The strip was popular enough to spawn a series of live action one-reel films (a few of which survive), but Fisher thought it might be better suited for a cartoon, which by 1916, was a new happening thing.

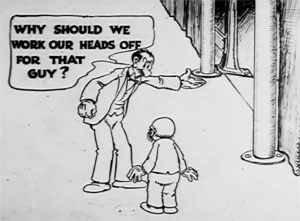

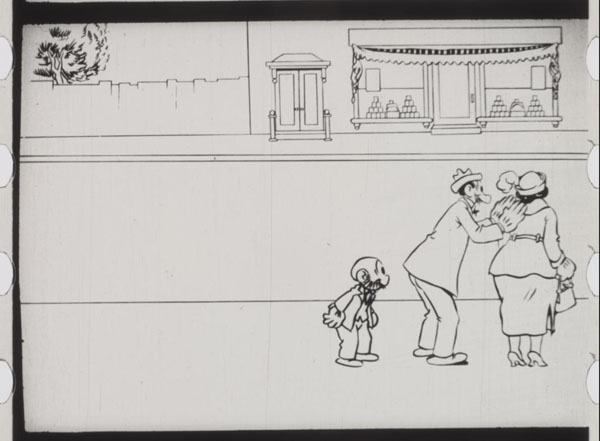

A frame from “On Strike”

Bowers continued making cartoons until October 1917, when he was joined by artist/animator Raoul Barré. They formed Barré-Bowers studios, and Barré’s staff joined Bowers’ to make the production of extra cartoons more feasible. The idea was to get as much out as possible. Klein and Huemer describe a highly collaborative atmosphere. They would sketch out a story, chop it into scenes, and each artist completely animated a particular scene. So long as the last frame of the scene got to the point of the next one, the animator was free to do whatever he wanted.

This continued through December 1917, when Fisher was drafted into WWI. Shortly after (March 1918), Fisher signed a deal with Fox, which now became the distributor for the cartoons (they had been States’ Rights independent films up to this point).

At this point, there’s some haze in the history. With Fox taking over, there seemed to be more interest in actual accounting than Fisher had been willing to do. Somewhere in this period, Barré left the studio. It was after October 1918, since there is an article from that time stating that Barré’s wife has sued him for support, claiming he was spending too much time at the studio.

The commonly told story is that Barré left, having a nervous breakdown, and saying Bowers was a crook. The only verification I can find on this is from Bowers himself being repeated to people who worked there. I don’t trust Bowers’ account on this, because Bowers actually was a crook, and Barré was wise to get out.

Fox sent some accountants to the studio, and discovered that Bowers was paying his staff in cash, less than the money that he was billing to Fox, and then pocketing the difference. Fox abruptly fired Bowers, and continued without him.

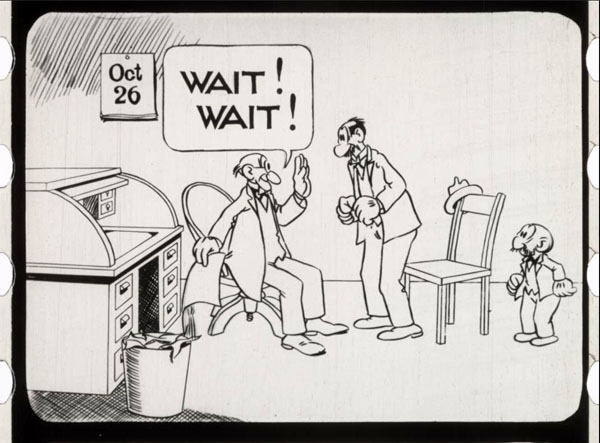

“AWOL” (1919)

Bowers decided he was going to start his own studio and make Mutt and Jeff cartoons himself. He hired Isadore Klein, who recounts the story in his memoir. Klein and Bowers holed up in quarters in Mount Vernon, NY, and animated their own cartoon, A Trip to Mars (1920). It was photographed surreptitiously by the animation camera in New York City, with one change: the guys there were on to the ruse and changed the title to Chuck and Izzy in A Trip to Mars. The title was corrected and the cartoon released. It does not survive.

Apparently, Fox and Fisher were both pleased with this arrangement, and they continued to purchase cartoons from Bowers, since they were in desperate need of any product. The New York studio and the Mount Vernon studio continued to work in parallel until late 1922. Bowers eventually got his own animation camera, and films were shot there. The last cartoon was released in early 1923. You can see the reason why. Even by 1921, the animation look was dated. They were using the older slash method to avoid patent royalties, something that required more effort and made for extremely jittery animation.

Klein reports that Bowers was increasingly unmotivated about the series as it moved on, preferring to experiment with stop motion, which was his next gig. Bowers worked less and less on each cartoon.

“Not Wedded But A Wife”

In 1926, Bowers started with FBO and began his stop motion career.

The cartoon I found is from 1921, and is in the period that Bowers was working in tandem with the other studio. It’s impossible to say whether Not Wedded But a Wife is a genuine Bowers cartoon or not. Even if it had been done by his studio, it would have been a collaboration with other animators. As it stands, the cartoon isn’t very good. It’s a rehash of the stage play Seven Chances (1916) with lots of racist gags, and some vaguely homophobic and transphobic gags. It packs a lot of offense into six minutes.

But back to the present. After a lot of shuffling, I managed to convince ASIFA-Hollywood and NFPF to fund a restoration of the cartoon. That meant only that I could get the cartoon properly saved, but the mystery was unsolved. I realized that the only way left to identify the cartoon’s art was to ask animation experts from the period what they thought.

It was then I got into the politics of modern day:

“I think you’re selling this as a Bowers cartoon, and you don’t know it is. I do/don’t think it is.”

“I’m working on a book and I have some research that I don’t want to share.”

“I’m not interested in this cartoon unless I have exclusive world rights to it.”

I discovered that cartoon historians can be an unfriendly lot, much as film collectors themselves tend to be. That’s the fuel for an entirely different article. I did get a fair amount of cooperation, but it took some cajoling.

Since we know (or think we know) that AWOL is a completely Bowers creation, I thought that it was important to compare the figure drawing in it to the figure drawing in Not Wedded But a Wife. I discovered that the female figures have a distinctly Bowers-like look. Others have disagreed.

The consensus is that there is no consensus yet. Serge was right. We just don’t know which cartoons Bowers worked on, and I only muddied the waters.

There are several key questions I still don’t have answers for:

When did Bowers get fired?

When did Barré leave?

Why did Barré leave?

I discovered some new mysteries as I did the restoration. The end title looked to be replaced. I contacted a couple of archives to see if they had any unrestored Fox end titles for Mutt and Jeff cartoons. Turns out Library of Congress had one in bad shape. It has an end title identical to mine. Why, then, is it haphazardly spliced on?

Not Wedded But a Wife is shot on two different cameras. This, sadly, is a bit of information that will go away in the restoration and will only be shown in the nitrate print, since the original cartoon actually contains data outside the projectable frame edge. In 1921, the idea of changeable aperture plates had not come into being, and yet, there are two different apertures in the cartoon.

The opening and closing are shot with one camera, while most of the middle is shot with a different camera using a rounded camera aperture, which became more common later.

Camera aperture #1: rounded corners, straight edges, and definite right edge.

Note crooked bottom line and arched left side with no stop at right.

What does this mean? Had the two studios declared a truce by 1921 and allowed cross-pollination? Did one camera break during production and get replaced by another? I can’t answer this.

Maybe someone, some day, will find answers I haven’t found. I’m always glad to find out new things. Perhaps deep in the index of one of those “in-progress” books I heard about is a primary source document that will end the argument.

Some day, I hope to release Not Wedded But a Wife on a DVD/Blu-ray set and open the dialogue even further.

After all, how hard can that be?

Steve Stanchfield is an animator, educator and film archivist. He runs Thunderbean Animation, an animation studio in Ann Arbor, Michigan and has compiled over a dozen archival animation DVD collections devoted to such subjects at Private Snafu, The Little King and the infamous Cubby Bear. Steve is also a professor at the College for Creative Studies in Detroit.

Steve Stanchfield is an animator, educator and film archivist. He runs Thunderbean Animation, an animation studio in Ann Arbor, Michigan and has compiled over a dozen archival animation DVD collections devoted to such subjects at Private Snafu, The Little King and the infamous Cubby Bear. Steve is also a professor at the College for Creative Studies in Detroit.

I Know This Is Not About This But What’s The Latest Update Of The Van Beuren’s Tom And Jerry

Blu-Ray I Want To Hear More About It

Steve,

Are the various Thunderbean projects like Flip or Rainbow Parade still coming, or has this virus slowed everything down?

“I discovered that cartoon historians can be an unfriendly lot….”

Present company excepted, I’m sure.

Thank you for sharing your story, Eric, and believe me, we fans of early animation appreciate everything you do. Whether it’s a Bowers cartoon or not, it’s still worth preserving as documentation of the art form’s development. I hope to see “Not Wedded But a Wife” when you’ve made it available on home video. Any chance of a centenary release next year?

I’m obligated to finish King of the Kongo by grant work. I’m having a great deal of trouble with it due to some nitrate decomp in it that I need to remove. As soon as it’s finished, I hope to get to another couple of projects. That’s the trouble with these things. You’re never sure of how bad they are until you start them! Little Orphant Annie was a mess of different sources and various framing problems. Kongo is a mess of decomp and sound issues.

Fantastic article, Eric! As a fan of both the Charley Bowers two-reelers and the Mutt and Jeff silent cartoons, I certainly applaud your efforts in locating, funding and restoring this cartoon and hope to see it pop up on one of your Blu-ray/DVD sets sometime soon. I enjoyed your release of Little Orphant Annie a lot more than I thought I would, and am certainly looking forward to King of the Kongo and Dynamite Dan!

Thanks also for your succinct account into the somewhat chaotic behind-the-scenes production changes. With only “a dozen or so” survivors from this period, I’m sure we all hope unearthing more “lost” shorts or some currently inaccessible documentation would at least shed some light to the many mysteries you’ve highlighted.

Back when I coordinated a course on animation history, I used Bowers as proof that animation at that point had become profitable enough to embezzle from. But what a visual genius. The sequence where a mechanical stuffed glove meticulously creates a doll remains utterly stunning. Thank you for this posting!

You often see fierce debates in art history as to whether or not a painting was done by a particular master, or his pupils. They use a lot of terms like “School of Raphael,” or “Follower of Raphael” or “Circle of Raphael.” Here’s one set of definitions, as used by some auction houses:

“By”: If a painting is labeled as “by” Raphael, the auction house stakes its reputation that the work is made by the hand of the artist. And the price will reflect that.

“Attributed to”: The painting is probably by the artist, at least in part, but the auction house isn’t 100 percent sure.

“Studio of”/“Workshop of”: A work executed in the studio or workshop of the artist, possibly under his supervision. But someone other than the famous name actually created the work.

“Follower of”: A work executed in the artist’s style but not necessarily by a student, or anyone who worked directly with the artist.

“Circle of”: The auction house thinks this work is from the same period of the artist and shows his or her influence. (Still, it’s a little more distant than “Follower of.”)

“Manner of”: A work done in the style of the artist but at a later date.

“After”: A copy of a work by the artist.

“School of”: Perhaps the most wiggly description of them all, which suggests some unifying aspect to diverse artworks that may not exist. “American School,” for example, refers to no school in particular but identifies the artwork as having been created in the United States, while “Continental School” means somewhere in the broad expanse of Europe but not England.

Seems to me that you could well apply this to the cartoon in question. On another note, some of those cartoon historian-type comments make me wince. I’ve always been of the view that anything I find gets shared. Such as it is.

GREAT work. Some of these names — I mean their work — shows up in old magazines, CARTOONS, Judge; etc. Have they all been combed? I have complete runs… which would shed light on their animation work, more how they moonlighted, I guess, for coffee money. Or to compare drawing styles?

We premiered NOT WEDDED at Cinecon last year, and judging from their reaction, the audience found it a lot better than “not very good!”