Millions have watched and enjoyed cartoons produced by the Fleischer/Paramount/Famous studios for nearly six decades. Far fewer are aware of the men and women who worked on them, from Koko the Clown and Betty Boop through the Harveytoons of the 1950s and beyond.

From the Fleischer Superman cartoon “Terror On The Midway”, the position of Calpini’s credit is a tip off that he actually directed the cartoon.

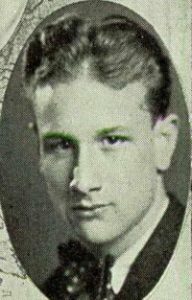

One stalwart who remained virtually unknown for those many decades was Orestes Calpini. Rarely credited, Calpini was a writer, director, and animator from 1933-1972 while drawing comic books for Hillman Periodicals from 1944-1951. Calpini contributed to two feature films, 38 animated shorts, and a short-lived television series. His sister, Hemia, was a talented painter who had also briefly worked at Fleischer.

Calpini was born on March 17, 1911 in New York. His sister Hemia was born in 1908, and both evidenced an artistic bent. Calpini went to work for the Fleischer Studios as a young man, only some twenty years old; due to the studio practice of crediting only two animators per film, his animation work is uncredited on the 1933 Popeye short Wild Elephinks.

To demonstrate how early in the Popeye series Calpini made his debut, at the time, William Costello was the voice of Popeye, and Bonnie Poe voiced Olive Oyl. Calpini would not receive his first animation credit until 1936 for his work on Let’s Get Movin’.

Although Calpini worked on only sixteen Popeye cartoons, his work as an animator soon led to directorial roles and eventually his own animation unit at the studio when Fleischer started their first feature film. Calpini animated Popeye in some early scenes in the renowned 1937 Popeye short Popeye the Sailor Meets Ali Baba’s Forty Thieves.

Calpini did a lot of heavy lifting on the 1939 film Gulliver’s Travels. Already one of the more experienced animators at Fleischer (along with Myron Waldman, Willard Bowsky, James Culhane, and Roland “Doc” Crandall), Calpini had the dual task of animating and training the influx of (often inferior and inexperienced artists) who flocked to Miami from the West Coast.

(Calpini’s sister Hemia joined Orestes as a set and background artist on Gulliver’s Travels and the subsequent and final Fleischer feature Mr. Bug Goes to Town in 1941. Hemia was a fine painter whose silkscreen work is still available at auctions. Her work likely appears in the scene where the bugs gather the necessities for Honey’s wedding in Mr. Bug).

Calpini would have one more moment of glory before a financial takeover by Paramount Pictures. Paramount wanted an animated version of DC comics Superman, the phenomenally popular superhero created in 1938. This series of cartoons was a challenge, as it demanded a hyperrealistic style complete with special effects and techniques such as shading on the characters. The first of an eventual seventeen cartoons, Superman (aka “The Mad Scientist”) appeared in 1941.

Calpini’s work on the series began in 1942 under the auspices of Paramount. He directed the fifth cartoon, The Bulleteers. Later that year, Calpini also directed Terror On The Midway (embed below). He co-directed (with Dan Gordon) his final Superman cartoon, Jungle Drums, in 1943.

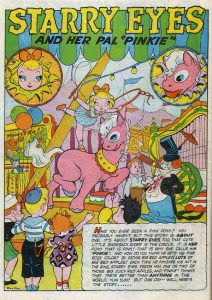

Calpini stayed active during the Paramount/Famous Studios regime until his final cartoon, Little Brown Jug (released in 1948). Calpini left Famous on September 27th, 1946, according to Al Eugster’s journal (via Mark Mayerson). During this time, he joined fellow animator Joe Oriolo in the field of comic books. Oriolo created a series called Punch and Judy, which he sold to Hillman Periodicals in 1944. The comic featured a living marionette (Punch) and his young human companion (Judy). The comic book lasted for 32 issues, ending its run in 1951. Calpini created characters and drew stories (along with a young artist named Jack Kirby) for editor Ed Cronin, another Fleischer veteran.

In 1962, Max Fleischer collaborated with his former animator Hal Seeger to produce an all-new color series of Out of the Inkwell cartoons for television. Orestes Calpini signed on as an animator. Koko the Clown was revived, now in the company of his girlfriend Kokette and companion Mean Moe. Larry Storch provided the voicework, along with Seeger’s wife, Beverly Arnold, who voiced Kokette.

This dreary series lasted one year and featured poor animation, insipid stories, and none of the creativity of the original Out of the Inkwell cartoons. It must have meant little more than a paycheck for Calpini, who doubtless recalled the glory of the early Fleischer days.

Once an animator, always an animator. Per animator Nancy Beiman, Calpini resurfaced in the early 1970s at Jack Zanders’ Animation Parlor in New York. Zander had once been an animator in Calpini’s unit at Fleischer. Calpini’s final efforts in Zanders’ employ involved animating commercials.

A true animation industry veteran, Calpini is perhaps less known than many of his contemporaries. Orestes Calpini passed away on December 3rd, 1974, at the age of 63. His sister Hemia followed him in death in July 1988, having contributed her talents to the Fleischer Studios’ two feature films.

SPECIAL THANKS to Devon Baxter for providing illustrations to this post.

Martin Goodman is a veteran writer specializing in stories about animation. He has written for AWN and Animation Scoop – and lives in Anderson, Indiana.

Martin Goodman is a veteran writer specializing in stories about animation. He has written for AWN and Animation Scoop – and lives in Anderson, Indiana.

The name of Orestes Calpini was familiar to me by my teen years from the animator credits of the Fleischer Popeye cartoons. It stood out because I knew the myth of the Greek hero Orestes, who slew his mother and her lover to avenge the murder of his father, King Agamemnon. Calpini’s father was born in Italy, his mother in Mexico. I’ve been told that when Mexican parents give their children names from Classical antiquity, rather than those of Christian saints, you can be sure that they’re free-thinkers.

Calpini’s name was usually paired with that of Willard Bowsky, and as a youth I was conscious that the animation in those cartoons was of an exceptionally high quality even by the standards of the Fleischer studio, matched only by the team of Seymour Kneitel and Roland Crandall.

By coincidence I saw “Terror on the Midway” again just yesterday, on the Bosko Video/Image Entertainment Diamond Anniversary Edition DVD from which the above YouTube video was taken (as evinced by the subtitle giving the original release date). I understand that this collection was assembled using the best film elements available, and it therefore might be the best we fans can hope for; but it’s a shame that much of the cartoon’s striking detail is obscured in this dark, murky print.