Back-to-back hits. Don Bluth had that in the late 80s, with An American Tail in 1986 and The Land Before Time in 1988. They established Bluth and his Studio as a force to be reckoned with. Bluth, once a Disney animator who led a walk out of his peers from the Studio in 1979, had emerged as a major competitor with Disney.

Back-to-back hits. Don Bluth had that in the late 80s, with An American Tail in 1986 and The Land Before Time in 1988. They established Bluth and his Studio as a force to be reckoned with. Bluth, once a Disney animator who led a walk out of his peers from the Studio in 1979, had emerged as a major competitor with Disney.

“That was a tremendous ‘buzz,'” recalled Bluth in a 1997 interview. “What we learned during that period was that if you have the right marketing, your picture has a chance to get its own legs. There was a man named Brad Globe, who was working at Amblin at the time we did both the pictures, and he had a great idea, which was ‘Let’s have a marketing tie-in so that the studio, Universal, doesn’t have to pay for the entire exposure of this picture.’ So, he brought in McDonald’s and got them excited about a symbiotic relationship with the Studio. There was about $50 million dollars spent in making the public aware of the pictures, just by the marketing tie-in people. That opened up a whole new vision of how to promote a motion picture.”

Into this era of precisely marketed films came Bluth’s next, All Dogs Go to Heaven, in 1989, which had a similar model. However, it also had the misfortune of opening in theaters the same day as Disney’s The Little Mermaid, which garnered glowing critical acclaim. It rekindled the Disney’s fairy tale legacy and kicked off its unprecedented renaissance age.

While All Dogs Go to Heaven, which celebrates its 35th anniversary this month, didn’t reach the heights of The Little Mermaid, many remember it, and not just from repeated VHS viewings when they were kids. Aficionados see it as an attempt to try something different in animation.

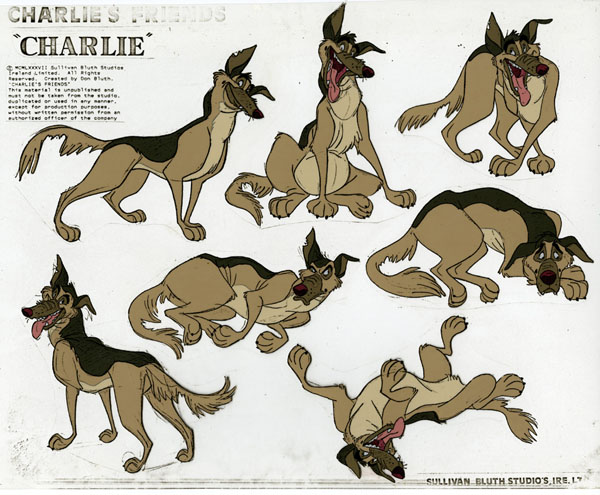

Set in New Orleans in 1939, the film centers on Charlie, a German Shepherd who is double-crossed and killed by the canine gangster Carface. Charlie goes to Heaven but escapes, returning to earth to reunite with his best friend, Itchy, and conspires revenge on Carface.

Charlie and Itchy wind up befriending a young girl named Anne-Marie, who Carface has kidnapped. Charlie rescues and saves Anne-Marie and learns a selfless lesson.

One of the major promotional points of All Dogs Go to Heaven was that it featured the voices of Burt Reynolds as Charlie and Dom DeLuise as Itchy. Famous friends in real life, the two recorded their sessions together, which allowed them to add-lib.

The cast also included Vic Tayback as Carface, Charles Nelson Reilly as Killer, a nervous dog who serves as Carface’s sidekick, Loni Anderson (then Reynolds’ wife) as a collie named Flo, Melba Moore as an angel dog in Heaven, Ken Page as King Gator, who sings a musical number with Charlie, and as Anne-Marie, child actress Judith Barsi (who tragically died, killed by her father, a year before the film was released).

All Dogs Go to Heaven was produced at Sullivan Bluth Studio, an animation studio based in Dublin, Ireland, that Bluth had founded with his regular collaborating producer Gary Goldman, animator John Pomeroy, and businessman Morris Sullivan.Bluth and his Studio were initially headquartered in California but transitioned to Ireland during the production of The Land Before Time. All Dogs Go to Heaven would mark the Studio’s first film not connected with Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment.

As its title conveys, All Dogs Go to Heaven has some darker, more adult moments. As the film opens, Charlie is on “death row” at the city pound, when Itchy frees him. Carface and Charlie own a nightclub that features gambling, smoking, and drinking, and Carface “bumps off” Charlie by pushing a car at him down a long dock.

When Charlie leaves Heaven, he steals his “life watch,” which he plans to rewind and get his life back. However, he’s told that he can never return to Heaven, leaving the specter of the other alternative hanging over the movie’s plot.

These aspects didn’t go unnoticed by critics when All Dogs Go to Heaven opened on November 17, 1989. The New York Times critic Janet Maslin wrote, “…as children watching Don Bluth’s new full-length animated feature are sure to surmise, is that all dogs die. Anyone not wishing to discuss this idea and its greater implications on the way home from the theater would be well advised to think twice before taking a small child.”

However, some critics, like Roger Ebert, enjoyed the film’s decidedly different take, as he wrote: “…in his latest animated feature, Don Bluth has allowed his characters to look and behave a little more strangely. There’s a lot of individualism in this movie, both in the filmmaking and in the characters.” Many have embraced this about All Dogs Go to Heaven in the three and a half decades since it opened.

However, some critics, like Roger Ebert, enjoyed the film’s decidedly different take, as he wrote: “…in his latest animated feature, Don Bluth has allowed his characters to look and behave a little more strangely. There’s a lot of individualism in this movie, both in the filmmaking and in the characters.” Many have embraced this about All Dogs Go to Heaven in the three and a half decades since it opened.

The film didn’t ignite the box office like Bluth’s other animated films at the time, but it was received well enough to warrant a sequel in 1996, a TV series, and a direct-to-video Christmas Carol film. None of these involved Bluth.

Bluth followed up All Dogs Go to Heaven with 1992’s disappointing Rock-A-Doodle, and the Sullivan Bluth Studio experienced financial difficulties, leading to many artists’ layoffs.

“It was a hard thing when the Studio went through all of its troubles in Ireland,” Bluth said in ’97. “It was very difficult, more so because I felt bad for all the people we had trained who weren’t sure what they were going to do now for a living.”

Bluth’s next major hit would be 1997’s Anastasia, which came after several challenging years, but, reflecting on that time after All Dogs Go to Heaven, Bluth noted, “I know this, all the bumps in the road are there for a reason, they teach you things and you learn from them. Usually, when you come back from those experiences, you’re stronger.”

Michael Lyons is a freelance writer, specializing in film, television, and pop culture. He is the author of the book, Drawn to Greatness: Disney’s Animation Renaissance, which chronicles the amazing growth at the Disney animation studio in the 1990s. In addition to Animation Scoop and Cartoon Research, he has contributed to Remind Magazine, Cinefantastique, Animation World Network and Disney Magazine. He also writes a blog, Screen Saver: A Retro Review of TV Shows and Movies of Yesteryear and his interviews with a number of animation legends have been featured in several volumes of the books, Walt’s People. You can visit Michael’s web site Words From Lyons at:

Michael Lyons is a freelance writer, specializing in film, television, and pop culture. He is the author of the book, Drawn to Greatness: Disney’s Animation Renaissance, which chronicles the amazing growth at the Disney animation studio in the 1990s. In addition to Animation Scoop and Cartoon Research, he has contributed to Remind Magazine, Cinefantastique, Animation World Network and Disney Magazine. He also writes a blog, Screen Saver: A Retro Review of TV Shows and Movies of Yesteryear and his interviews with a number of animation legends have been featured in several volumes of the books, Walt’s People. You can visit Michael’s web site Words From Lyons at:

Wasn’t Bluth’s “The Secret of Nimh” actually his first film not connected to Spielberg’s Amblin? (three years till its 45th anniversary, btw–I hope it gets a retrospective like this one.)

That was four years before “An American Tail”.

No doubt Don Bluth was a force to be reckoned with. I recall the release of “The Secret of NIMH” and I could tell that something new was in the wind regarding animated films. Much as I enjoyed “An American Tail,” I always felt that NIMH was the real breakthrough.

While the afterlife was not a new concept to animation, it usually had been relegated to the last few seconds of a cartoon. There were exceptions, such as “Heavenly Puss” with Tom and Jerry or “Heavens to Jinksy” with Pixie and Dixie (plus one involving Sylvester and another involving Yosemite Sam that I can think of), but for a mainstream family animated film to deal with death and the afterlife so openly must have been a daring step for the late 80s, a time when much of the animation was aimed squarely at young, impressionable children instead of the adults who were the target audience in the 40’s and 50’s.

Though I missed it in the theaters, the first time I caught “All Dogs Go to Heaven” was on a premium channel on television (uncut with no commercials). I was not feeling well at the time, and so the film’s take on mortality was hitting close to home. It did keep me engrossed throughout, although at the time I was struck with the impression that the film did feel very “adult.”

What perfect timing to post this on All Saints’ Day! I like to think it was more than coincidence?

I loved all the movies, and the TV series. Ernest Borgnine replaced Tayback as the voice of Carface. Makes me wonder why Killer didn’t appear in “All Dogs Go To Heaven 2”, but got a chance in the TV show instead. And in my opinion Annabelle and Sasha were grand enough to attract female viewers. I love those two.

As for Charlie, I’m surprised that he’s come a long way after the original movie, especially with Steve Weber giving him more emotion.

I’ve seen neither this film nor The Little Mermaid but I prefer Bluth to 80s Disney, so I bet I know what my choice is!

I don’t know about you guys but I always thought The Great Mouse Detective seemed more like Bluth than Disney.

“All Dogs Go to Heaven” exemplifies a peculiarly “Hollywood” view of death and the afterlife, one not espoused by any religion: the idea that, under certain circumstances, a decedent can come back to life to right wrongs or take care of unfinished business. We all remember Clarence, the angel under probation in “It’s a Wonderful Life”, who has to come to Bedford Falls in order to prove to George Bailey that life is really worth living. In “Angel on My Shoulder”, a murdered gangster (Paul Muni) gets a second chance at life through a deal with the devil that quickly falls apart. In “Goodbye Charlie”, a womanising playboy murdered by a jealous husband is reincarnated as a woman (Debbie Reynolds). (I think it’s no coincidence that Carface’s parting words upon dispatching his former partner are “Goodbye, Charlie!”) The trope would reach its ne plus ultra in Michael Landon’s laughably maudlin TV series “Highway to Heaven”, in which angel Jonathan Smith, like Clarence, has to travel around doing good deeds in order to “earn his wings.” “All Dogs” might be a unique example of the genre as far as animated features go, but it has a lot of company in the wider scheme of things.

The Netflix animated series “Bojack Horseman” has a running gag where three little boys in a trench coat and false moustache go around pretending to be a grown man, and the disguise fools absolutely everyone except for Bojack himself. I wonder if that might have been inspired by the escapades of Anne-Marie, Charlie and Itchy betting on the races in “All Dogs”.

The terrible tragedy of Judith Barsi’s short and unhappy life makes her performance, especially the song where Anne-Marie yearns for a happy family, absolutely heartbreaking.

Don’t forget Jacob Marley.

I don’t know, Pete. Marley’s ghost is, well, a ghost. He doesn’t come back to life in our world, and his admonitions to Ebenezer Scrooge don’t affect Marley’s own status in the afterlife.

I swear there was a post about ADGTH here, merely 2 weeks ago. Mandela Effect?

I’ll repeat(?) myself, the explanation of the music loving alligator being old friends with Carface (there was betrayal) should have been put in the movie. I know that was planned. A shame this did not happen, would have improved the movie A LOT.

All Dogs Go To Heaven is one of my favorite Don Bluth movies. One sequence I particulary like is Charlie’s nightmare sequence where he dreams he goes to Hell and encounters demons very reminiscent of Hieronymus Bosch.

Bluth’s post-ADGTH, pre-Anastasia movies don’t really work for me with the exception of the entertaining Rock-A-Doodle.

But I do admire Bluth for trying to do something different.

Is Anne-Marie dessed in homage to Snow White? In the cel pictured, I’m getting definite Snow White vibes.