The 1936-37 season saw the “suits” at Loew’s Incorporated starting to look at the budgeting for their cartoons. The films had been becoming more elaborate and more expensive with each passing season. Furthermore, the number of cartoons released per season was dwindling, cutting into the ability to gain revenues for the films over the year in regular bookings. The live action shorts were pulling their weight in comparison, while the cartoons must have been dragging the bottom line. Although the effects of this scrutiny would not be felt until the next season, some of the finale action in the Little Ol’ Bosko (or “Grandma’s Cookies”) trilogy, for example, certainly would have been costly to mount, and would soon become beyond what the cigar-chompers in New York would tolerate.

The 1936-37 season saw the “suits” at Loew’s Incorporated starting to look at the budgeting for their cartoons. The films had been becoming more elaborate and more expensive with each passing season. Furthermore, the number of cartoons released per season was dwindling, cutting into the ability to gain revenues for the films over the year in regular bookings. The live action shorts were pulling their weight in comparison, while the cartoons must have been dragging the bottom line. Although the effects of this scrutiny would not be felt until the next season, some of the finale action in the Little Ol’ Bosko (or “Grandma’s Cookies”) trilogy, for example, certainly would have been costly to mount, and would soon become beyond what the cigar-chompers in New York would tolerate.

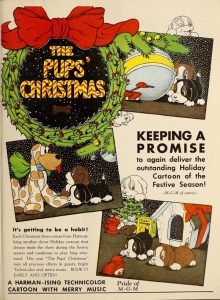

The Pups’ Christmas (12/12/36) – MGM seemed to be trying to get as much mileage as they could out of two adorable puppies. This time, they are playfully cavorting among the Christmas gifts. Among the items the pups encounter is a toy WWI tank, which becomes a real menace, shooting sparks at the pups. It takes a counterattack and battle with a toy airplane to bring about the tank’s downfall. Songs: “Jingle Bells”, “Where Oh Where Has My Little Dog Gone”, and heavy use of “Over There”, George M. Cohan’s 1917 hit which became probably the best-known song of the war – providing a musical accompaniment for virtually every move of the tank. Victor had a red seal by Enrico Caruso, a black label by Bully Murray with the American Quartet, and a purple label with Nora Bayes. Columba gave it to Prince’s Band and to the Peerless Quartette (Albert Campbell, Henry Burr, Arthur Collins, and John Meyer). Dick Powell would later revive it for Decca.

Circus Daze (1/16/37) – Honey just will not shut up. She and Bosko, with Bruno tagging along, are heading for a circus, looking for thrills and amusement. Bosko keeps scolding Bruno for not lying down and being a peaceful dog. Honey is particularly annoyed by a couple of monkeys (a cameo for two of the Good Little Monkeys in their new design), who steal her balloon. Bruno pursues one of the monkeys’ fleas, and leaps right into the container of an elaborate flea circus, setting the insects loose everywhere, and creating utter chaos. Bosko and Honey emerge from the tent, barely avoiding an animal stampede, and Bruno is ejected forcibly onto the high-striker, ringing the bell. Songs: “Zampa Overture”, and “National Emblem March”, composed by Edwin Eugene Bagley. Said March was recorded both acoustically and electrically by Arthur Pryor on Victor, by Prince’s Band on Columbia acoustic, then by the Columba Band directed by Robert Hood Bowers electrically, Walter B. Rogers (both acoustic and electrical) on Brunswick, the New York Military Band on Edison cylinder, Hager’s Band on vertical-cut Rex in England, the Band of H.M. Scots Guards on English 8″ Radio, Conway’s Band on Okeh, the United States Marine Band on Victor, and the United States Army Band on Lincoln and Cameo. The American Legion Band of Hollywood recorded a 30’s version for Decca. Jazz versions appeared by Frankie Trumbauer on Varsity, and on Commodore by Sidney Bechet. H.M. Grenadier Guards recorded a later electric for English Columbia. The Boston Pops would issue a version for RCA in the 1950’s.

Swing Wedding (2/15/37) – There’s to be a wedding among the frogs, between Minnie the Moocher and Smokey Joe. Smokey Joe is the Stepin Fetchit frog, who seems incapable of putting on any speed, and is in no hurry to arrive at the wedding, until it appears Minnie may ditch the errant groom for the Cab Calloway frog. Froghorn (the Louis Armstrong frog), proves who is the better man, by blowing some hot swing cornet under Smokey Joe, sending him into a fit of spirited dancing. The spirit is contagious, and runs amuck among all the other frogs, including members of Calloway’s orchestra. A drug-reference gag is slipped by so quickly, the censor probably missed it entirely. The addicting effect of swing music is demonstrated as a trumpet player smashes his instrument over another frog’s head, then spots among the broken components one of its valves, which he uses to inject himself in an arm vein in the manner of a hypodermic needle, setting him off into even more heightened frenzy. The film ends with the chaos contnuing, and Froghorn happily sinking into the pond, muttering, “Swing…. swing.” Songs: “Minnie the Moocher’s Wedding Day”, a sequel to the original “Minnie the Moocher “, perfored by Cab Calloway on Brunswick, and also by the Boswell Sisters on Brunswick. Victor gave it to Billy Banks and his Orchestra. A version was recorded for Columbia by Fletcher Henderson but seems not to have been issued here, instead appearing on British Parlophone as “Horace Henderson”. Roy Fox did one for English Decca, with Al Bowlly on vocal. An aircheck by Benny Goodman appeared on Columbia’s “Swing Concert No. 2″ LP set, actually culled from various radio broadcasts. The frenzied jam at the end of the cartoon s set to “Runnin’ Wild”, a 1922 pop song, which became an evergreen among jazz and swing musicians. The Cotton Pickers (an augmented version of the Orignal Memphis Five, adding a full rhythm section) would produce an early acoustic version for Brunswick. It is hard to tell if the same group would also perform it as “The Southern Serenaders” for Cameo.

Yet another seeming to be the same group was issued by the “Southland Six” on Vocalion. Also performed by them as “Ladd’s Black Aces” on Gennett. Columbia would give its acoustic version to Ted Lewis. Marion Harris would record an acoustic vocal for Brunswick. Miss (Isabelle) Patricola and the Virginans would also provide a vocal version on Victor. Joseph Samuels’ band issued a Grey Gull side, possibly derived from Paramount. Nora Bayes issued one of her last performances on Columbia. The Novelty Jazz Band under the direction of Billy Arnold would issue a sapphire-cut French version for Pathe. Duke Ellington recorded it under the name “The Jungle Band” in 1930 for Brunswick. Jimmie Lunceford covered it for Decca in the 1930’s. Red Nichols and his “World Famous Pennies” would receive an issue in 1934 on buff Bluebird. The Benny Goodman Quartet would give it a ride on Victor. The Emilio Carceras Trio (Carceras on violin, Ernie Carceras on clarinet, and Johnny Gomez on guitar) issued a similar Victor side in 1937. Ted Weems had an issue on Decca. Joe Daniels and his Hot Shots in Drumnastics would record for British Parlophone, a side imported here on Decca. Glenn Miller issued a version on Bluebird. The Fred Feibel Quartet (Hammond organ) would issue a 40’s side for Okeh. Harry Parry and his Radio Sextet would issue a 40‘s performance on English Parlophone. Maestro Paul Lavalle and his Woodwindy Ten would get an issue on a Victor set in connection with the Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street program. Art Tatum would perform a solo on ARA. The Teddy Wilso Quartet would get it on Musicraft, circa 1945. The Chordettes would issue it as an album cut on the 10″ LP “Harmony Time v. II” for Columbia in an a capella barbershop arrangement. Les Paul and Mary Ford would electrify it for Capitol. The Modernaires would also croon it on Coral. The Firehouse Five Plus Two of course covered it on Good Time Jazz. There is an Earl Hines version from an unknown label, sounding as if recorded in the 1050’s. Sid Phillips and his Band issued an HMV single in 1955. The song would reappear in film in MGM cartoons of the early 1940’s, becoming the official opening theme of several Tom and Jerry and Tex Avery issues. Further included in this cartoon is “Sweethearts on Parade”, a song written by Carmen Lombardo in 1928, performed by Froghorn. Louis Armstrong himself had had a hit on it, recorded for Okeh but released on the scarce Amerucan Parlophone and Odeon labels, then reissued on Columbia in 1932. Guy Lombardo’s original version was on Columbia in 1928. Victor gave it to Gene Goldkette. Brunswick gave it to Abe Lyman. There was a vocal version by Johnny Marvin on Victor. Lionel Hampton issued a Victor version around 1940. Nat Kng Cole revived it for Capitol. It also appeared on a Verve LP joint bill, “Krupa Meets Rich”.

Yet another seeming to be the same group was issued by the “Southland Six” on Vocalion. Also performed by them as “Ladd’s Black Aces” on Gennett. Columbia would give its acoustic version to Ted Lewis. Marion Harris would record an acoustic vocal for Brunswick. Miss (Isabelle) Patricola and the Virginans would also provide a vocal version on Victor. Joseph Samuels’ band issued a Grey Gull side, possibly derived from Paramount. Nora Bayes issued one of her last performances on Columbia. The Novelty Jazz Band under the direction of Billy Arnold would issue a sapphire-cut French version for Pathe. Duke Ellington recorded it under the name “The Jungle Band” in 1930 for Brunswick. Jimmie Lunceford covered it for Decca in the 1930’s. Red Nichols and his “World Famous Pennies” would receive an issue in 1934 on buff Bluebird. The Benny Goodman Quartet would give it a ride on Victor. The Emilio Carceras Trio (Carceras on violin, Ernie Carceras on clarinet, and Johnny Gomez on guitar) issued a similar Victor side in 1937. Ted Weems had an issue on Decca. Joe Daniels and his Hot Shots in Drumnastics would record for British Parlophone, a side imported here on Decca. Glenn Miller issued a version on Bluebird. The Fred Feibel Quartet (Hammond organ) would issue a 40’s side for Okeh. Harry Parry and his Radio Sextet would issue a 40‘s performance on English Parlophone. Maestro Paul Lavalle and his Woodwindy Ten would get an issue on a Victor set in connection with the Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street program. Art Tatum would perform a solo on ARA. The Teddy Wilso Quartet would get it on Musicraft, circa 1945. The Chordettes would issue it as an album cut on the 10″ LP “Harmony Time v. II” for Columbia in an a capella barbershop arrangement. Les Paul and Mary Ford would electrify it for Capitol. The Modernaires would also croon it on Coral. The Firehouse Five Plus Two of course covered it on Good Time Jazz. There is an Earl Hines version from an unknown label, sounding as if recorded in the 1050’s. Sid Phillips and his Band issued an HMV single in 1955. The song would reappear in film in MGM cartoons of the early 1940’s, becoming the official opening theme of several Tom and Jerry and Tex Avery issues. Further included in this cartoon is “Sweethearts on Parade”, a song written by Carmen Lombardo in 1928, performed by Froghorn. Louis Armstrong himself had had a hit on it, recorded for Okeh but released on the scarce Amerucan Parlophone and Odeon labels, then reissued on Columbia in 1932. Guy Lombardo’s original version was on Columbia in 1928. Victor gave it to Gene Goldkette. Brunswick gave it to Abe Lyman. There was a vocal version by Johnny Marvin on Victor. Lionel Hampton issued a Victor version around 1940. Nat Kng Cole revived it for Capitol. It also appeared on a Verve LP joint bill, “Krupa Meets Rich”.

Bosko’s Easter Eggs (3/20/37) – Bosko and Bruno are trying to collect Easter eggs for Honey. Bruno doesn’t carry them carefully, and they all wind up busted. Honey is busy herself, arranging eggs in a chicken’s nest so they will hatch properly. The chicken is locked in a pen. Bosko spots the eggs, thinking they will make a great substitute for the busted ones, and swipes them. But the jig is up, when Joney recognizes where he got them. Bruno is forced to sit on the now-dyed eggs to hatch them. But the story has a happy ending, when chicks matching the colors of the dyed shells emerge from the nest, for a bright Technicolor finale. Songs: “Just Before the Battle, Mother”, appearing when Bruno is forced to sit on the nest – a Civil War song, appearing in nearly every Centennial retrospective collection LP of the 1960’s. Harry MacDonough and John Bieling (two tenors from the Haydn Quartet) issued an early version on Victor. J. W. Myers also issued a version on Columbia. Ernestine Schumann Heink issued a version on red seal Victrola. Arthur Fields got it on Grey Gull. Arthur Campbell and Henry Burr (tenors from the Peerless Quartet) replaced the Victor version in a later recording and are also credited on a rare Okeh vertical-cut version that seems to have escaped mention in company catalogs as ever issued. Edison gave it to Will Oakland on Amberol Cylinder and Jim Doherty on disc, while Emerson gave it to Frank Woods. Also, an original number, “Easter Time Is the Time For Eggs”, performed as a proto-rap song by Bosko.

Little Ol’ Bosko and the Pirates (5/1/37) – Bosko’s Mammy gives him a poke full of cookies to take to his Grandma. Bosko immediately starts out, but his imagination wanders, and he envisions an old hulk in the swamp as a pirate ship, and the frogs who reside there as jumping jive pirates, allowing for the return of the same troop of black frogs we met in “The Old Mill Pond” and “Swing Wedding”. Froghorn appears as the leader of these frogs, and gives orders for Bosko to surrender his cookies or walk the plank. This leads to a forwards-backwards counting dance by Bosko, which Harman and Ising seemed to love, using it twice in this cartoon and again in the next below. Bosko eventually gets the frogs into another swing dancing frenzy (without the drug reference of “Swing Wedding”), and Bosko emerges victorious from his dreamy reverie. Songs: “Straight To Grandma’s Here I Go”, another proto-rap by Bosko, and “We Can’t Get No Grandma’s Cookies Today”, a riotous number by the frogs, with Bosko’s dancing setting the pace.

Little Ol’ Bosko and the Cannibals (8/26/37) – Virtually the same plot as the previous film, with Bosko now envisioning himself washing up on a cannibal isle, with the frogs wielding huge shields and spears. Bosko’s mom has a longer monologue at the beginning, and the frogs seek to get Bosko to walk into a boiling pot rather than walk the plank into the sea. Froghorn himself takes the dip into the pot, emerging with a roasting bottom, and remarking “Is my face red.” Songs: a repeat of both songs from the last cartoon, plus another original which I’ll just call “Cookies”, sung by the frogs before most of the hoopla. It’s a wonder these cookies aren’t reduced to crumbs by the frenzied action of these episodes.

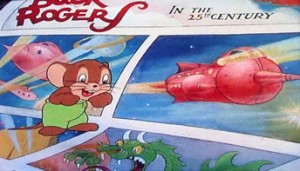

Little Buck Cheezer (12/25/37) – Cheezer’s Mama sends him to bed, with Cheezer going through that phase of ‘They just treat me like a little kid.” Cheezer’s playmates are outside at the window, marveling at the full moon tonight, and the mice decide to build a rocket ship, just like they’ve seen in the Sunday Buck Rogers comic strip (one of which is actually seen on screen), to figure out if the moon is really made of cheese. Even their tough-guy skeptic joins in (who appears to be voiced by Tommy Bond, “Butch” of the Our Gang comedies), as they build the ship out of tin cans, assorted bric-a-brac, and one large keg of TNT. The ship takes off on a wild journey through space, with the tough mouse looking a little green around the gills, probably looking for a convenient rail to heave over. They reach the moon, which really is cheese, and decide to land for a bite. But their anchor (with a plumber’s helper on one end) fails to hold, and after briefly getting stuck in a limburger swamp, the rocket fails to stop, shoots back into the sky, and explodes. But the fiery scene isn’t real after all, as Cheezer awakes from a dream, and decides nexr rime, he’ll just keep going to bed as mama tells him to. He wishes the audience, “Good Night.” Songs: a revisit of “Little Brown Jug”, and “The Jolly Coppersmith”, a popular band item, recordings of which exist as early as 1901. Sousa’s Band recorded it as a Columbia cylinder. The Edison Military Band issued a gold-moulded cylinder in 1902. Columbia’s “Climax” series issued a version by the “Climax Band”. A 7″ inch version by an anonymous band would appear for the Berliner disc trade on Zonophone records. Arthur Pryor received the exclusive on the number for Monarch and Victor, both acoustical and in a wonderful electric version which sadly does not appear to be available on the internet. The Columbia Band (probably directed by Charles Prince) covered it on Columbia. Prince would later re-record it circa 1923 on Columbia’s metallic copper “Flag” label. Bergh’s Band issued a version on Puritan. Walter B. Rogers’ Band issued a Brunswick acoustic version in 1920’s. The New York Military Band (a house band directed by Cesare Sodero) recorded it for Edison Diamond Disc. The Goldman Band issued it on Brunswick in 1934, re-released later in a set for Columbia. Al Melgard would many years later issue a version from the Chicago Stadium pipe organ on Audio-Fidelity in stereo, probably in the late 1950’s.

Little Buck Cheezer (12/25/37) – Cheezer’s Mama sends him to bed, with Cheezer going through that phase of ‘They just treat me like a little kid.” Cheezer’s playmates are outside at the window, marveling at the full moon tonight, and the mice decide to build a rocket ship, just like they’ve seen in the Sunday Buck Rogers comic strip (one of which is actually seen on screen), to figure out if the moon is really made of cheese. Even their tough-guy skeptic joins in (who appears to be voiced by Tommy Bond, “Butch” of the Our Gang comedies), as they build the ship out of tin cans, assorted bric-a-brac, and one large keg of TNT. The ship takes off on a wild journey through space, with the tough mouse looking a little green around the gills, probably looking for a convenient rail to heave over. They reach the moon, which really is cheese, and decide to land for a bite. But their anchor (with a plumber’s helper on one end) fails to hold, and after briefly getting stuck in a limburger swamp, the rocket fails to stop, shoots back into the sky, and explodes. But the fiery scene isn’t real after all, as Cheezer awakes from a dream, and decides nexr rime, he’ll just keep going to bed as mama tells him to. He wishes the audience, “Good Night.” Songs: a revisit of “Little Brown Jug”, and “The Jolly Coppersmith”, a popular band item, recordings of which exist as early as 1901. Sousa’s Band recorded it as a Columbia cylinder. The Edison Military Band issued a gold-moulded cylinder in 1902. Columbia’s “Climax” series issued a version by the “Climax Band”. A 7″ inch version by an anonymous band would appear for the Berliner disc trade on Zonophone records. Arthur Pryor received the exclusive on the number for Monarch and Victor, both acoustical and in a wonderful electric version which sadly does not appear to be available on the internet. The Columbia Band (probably directed by Charles Prince) covered it on Columbia. Prince would later re-record it circa 1923 on Columbia’s metallic copper “Flag” label. Bergh’s Band issued a version on Puritan. Walter B. Rogers’ Band issued a Brunswick acoustic version in 1920’s. The New York Military Band (a house band directed by Cesare Sodero) recorded it for Edison Diamond Disc. The Goldman Band issued it on Brunswick in 1934, re-released later in a set for Columbia. Al Melgard would many years later issue a version from the Chicago Stadium pipe organ on Audio-Fidelity in stereo, probably in the late 1950’s.

Pipe Dreams (2/5/38) – The three goody-goody monkeys return, still singing Bill Hanna’s lyric from “Good Little Monkeys”. As they wander about, they happen across various smoking apparatus, which arouses their curiosity. They soon are taking in long drags from a pipe, and end up dizzy and wilting from its effects. They meet up with three hobo cigars, who ultimately get them riding the rails on a train made of matchboxes. The train is held up by pipe cleaner bandits, leading to some explosive results as the train cars are set on fire, climaxed by the igniting of a water tower filled with lighter fluid. The three monkeys awake to find it was a smoke-induced dream, and have learned their lesson (although still exhaling smoke as they sing the final note of their song). Songs: Aside from the monkeys’ theme, an original number is sung in praise of a hobo’s life by “The Three Cigars”, some standard square dance tunes, and a Latin rumba that appears to be another original.

Next: 1938.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

That’s not the “Zampa” Overture played by the circus band in “Circus Daze”, it’s “Poet and Peasant”. Another circus band would play the “Zampa” Overture, and nothing else, in a much later cartoon, Walter Lantz’s “The Bandmaster”, starring Andy Panda.

The first song heard in “Swing Wedding”, “Mississippi Mud”, has long been a favourite of mine, as I used to play it with a ragtime orchestra in the ’90s. We always closed with it, because it’s such a fun, foot-stomping romp, and it was one of only two songs that I got to sing with the band. I substituted the word “darkies” in the original lyrics with “neighbours”, until one of the other musicians mistakenly thought I was saying a much worse word, after which I changed it to “people”. The plosive consonants always used to make my microphone pop, but then you can’t have everything.

“Mississippi Mud” was written in 1927 by 21-year-old Harry Barris, who, along with Al Rinker and Bing Crosby, was one of the Rhythm Boys, a vocal trio that performed and recorded with Paul Whiteman’s orchestra for three years. Their 1928 recording of the song is one of the earliest recorded performances of scat singing, in which Barris was particularly adept. It was also one of the songs they performed in the 1930 Universal musical “King of Jazz”; the trio can be heard scatting during the brief animated segment, the first animation ever filmed in Technicolor.

The Rhythm Boys broke up in 1931 when Crosby wanted to go solo, and Barris wanted to concentrate on songwriting. Whiteman promptly assembled another male vocal group, a quartet this time, calling it Paul Whiteman’s Rhythm Boys; they, too, recorded “Mississippi Mud”, thereby confounding generations of discographers. The original Rhythm Boys reunited only once, on Whiteman’s radio program in 1943, and they only sang one song. That song? You guessed it: “Mississippi Mud”.

Other songs by Harry Barris used in cartoons of the 1930s include “It Was So Beautiful”, sung by Cubby Bear in “Love’s Labor Won”, and “Little Dutch Mill”, featured in the eponymous Fleischer Color Classic. Harry Barris was also the uncle of Gong Show host Chuck Barris.

“Mississippi Mud” turned up in, of all places, an early episode of the sitcom “M*A*S*H”. Harry Morgan, before he joined the regular cast as Col. Potter, played a crazy general who asked an African-American soldier at a military tribunal to entertain the court with a song and dance number. When the soldier balked, the general broke into “Mississippi Mud” — and yes, he sang the original lyric “darkies”, on network TV in the 1970s and for years afterward in syndication. When Hawkeye and Trapper sing the song later in the episode, they replace the word with “they all”, which spoils the scansion of the line; but as I said before, you can’t have everything.

A much later episode referred to the song as well: When Hawkeye is about to commence some very risky surgery, he says “Time to beat your feet on the Mississippi Mud.” Someone on that show must have really liked that song.

The mechanical dancing minstrel seen briefly in “The Pups’ Christmas” was an actual toy called, if I may be forgiven for saying so, “Tombo, the Alabama Coon Jigger”. It was one of the first toys marketed by Louis Marx & Co., which would become the world’s largest toy company by the 1950s, making a nationwide craze out of the yo-yo (several times) and, still later, those Big Wheel tricycles that every little kid seemed to have in 1970. (A friend of mine collects Louis Marx toys. He doesn’t have a “Jigger”; they’re very rare.) The toy tank might also be a Louis Marx creation, as the company made a wide variety of toy military vehicles over the years. Louis Marx was very proud of his service in World War I, and he named five of his sons after U.S. generals.

Louis Marx & Co. also made a line of Buck Rogers toys in the 1930s, including spaceships not dissimilar to the one that Little Cheeser and his friends took to the moon.

So many great cartoons discussed here. There seems to be an omission of one major piece of music here. In CIRCUS DAZE The chaos that ensues when the fleas start to swarm is orchestrated by a piece called “the poet and the peasant“. This piece must’ve been public domain before the dawn of sound film, because there are so many instances of it in animated cartoons that I think it would take a post or series of posts like this in length, if not more the many, many films that it appears in. It is probably the finest use of this piece in the cartoon like this. They were so many details left out of your description, and I’m sorry that the entire film wasn’t actually posted here. So many great and jarring images left out. perhaps, one day, this cartoon will be fully restored so everybody could see its amazing amount of detail. It perhaps, one day, this cartoon will be fully restored so everybody could see. It’s amazing amount of detail. It’s exhausting! “Pipe dream“ is another cartoon I would like to see in full restoration so people could examine it more closely. I could say that for just about any of the happy harmonies cartoons discussed here.

The only one of these I’ve seen is Little Buck Cheeser, and something tells me that’s for good reasons. Four appearances of the redesigned Bosko might be too much in one swing, pun intended.

The “MGM ‘suits'” had cause to be concerned about the rising budgets of the Happy Harmonies; they were getting more elaborate but not necessarily better. Heavy-handed pretty much says it all, making some of the cartoons downright unpleasant. The colors are dark and drab compared to Disney’s and Warner’s more appealing palettes, the humor virtually nonexistent. Despite the obvious planning that went into these, some effects are clumsy: in “Pipe Dream,” when the Latin dancers’ shadows intersect, they’re still given individual outlines instead of becoming a single mass as shadows tend to do. And the characters hadn’t enough personality to catch on.

Just the same, “Swing Wedding” is a great cartoon, possibly because it’s entirely adult; the “injection” is truly shocking on its first viewing. Harman-Ising simply couldn’t do “cute”: the over-rendered big-eyed characters, even with sweet little lispy voices (that Disney and Don Bluth would do to death decades later), are vaguely frightening.

And Mayer wasn’t an animation fan anyway; probably none of the studio moguls was.

MGM was, apparently, none too happy about the cost overruns on Hugh and Rudy’s cartoons.

I have shown many of these y ongoing animation fests. They are crowd pleasers each and everyone. Especially love the gasps SWING WEDDING gets when the frog shoots up.

I always found it unusual that they made an African-American child the star of a big budgeted cartoon series in the mid-30s, especially one that isn’t so that malicious of a stereotype compared to other contemporary representations. Bosko does come across as a very likeable character.

With all of those factors to consider, I wonder what the intent was with the redesigned Bosko at the time and what audience, distributor, and exhibitor feedback was.

An interesting observation. It might also be noted, however, that simultaneous with these films, MGM was in its heyday of distributing live action shorts portraying the same lovable message regarding black youth – the Hal Roach Out Gang shorts, famous for their cast integration, which were just coming off the starring period of Stymie, and well into the process of making Buckwheat a star – one of the only Roach rascals who would continue with the studio through the conclusion of the series. Perhaps the restyling of Bosko was intended to draw an animated parallel to a fictional member of the Roach Gang.

That is very plausible, especially since shorts such as The Old House and Circus Daze have Our Gang vibes to them, now that I think about it.

Trivia: Harry Barris was Chuck Barris’ uncle.

Hello again! These were among the first cartoons I’d ever seen on television back in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

They are still vivid memories, especially the cartoons featuring the redesigned Bosko – now a fully realized human black child, and I agree with the comment above that this might have been inspired by the “our gang” comedies of that era. They did a wonderful thing by allowing a black child to voice, the character in the last three cartoons, – now dubbed, The Bosko Trilogy – Possibly because it almost seemed as if they had the same plot, running through them, although no reused animation, surprisingly enough, if I remember correctly. as always, I think all of you commenting here as well as the author of this wonderful series of posts, for clearing up exactly what some of the musical pieces in these cartoons were.

Isn’t it amazing that there were so many pieces and songs that were exclusive to these cartoons. you’ve got to wonder why, with the expensive making these cartoons, they never pushed the animation department to create a feature film! Yes, there were big budget fantasies like “the Wizard of Oz” in live action, but wouldn’t it have been a sensation if the animation department had created the feature film? We can only imagine.