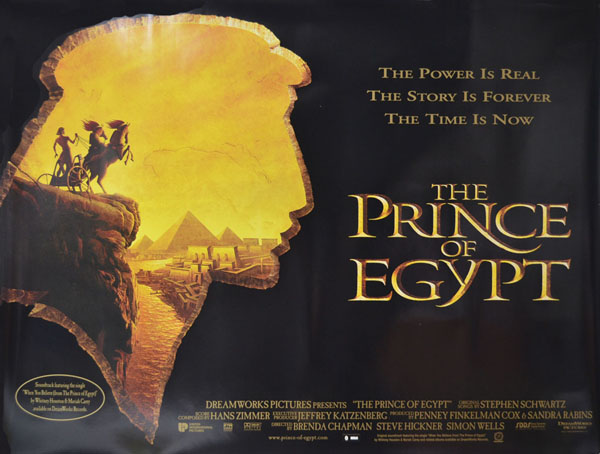

When DreamWorks announced The Prince of Egypt, a re-telling of the Biblical story of Moses, many were caught off guard by this choice for an animated feature.

As Chairman of The Walt Disney Studios, Jeffrey Katzenberg had been one of the forces to shepherd Disney into an animation renaissance that included films like The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), and Aladdin (1992).

When he left Disney in 1994, joining forces with Steven Spielberg and David Geffen to form a new studio, DreamWorks, SKG, it was announced that part of its productions would be animated features.

As a major competitor to Disney, many thought that traditional fairy tales and fables would be a large part of DreamWorks’ projects, but Katzenberg had something else in mind: the story of Moses.

The studio’s first feature out of the gate was the computer-animated Antz, a co-production with Pacific Data Images, but The Prince of Egypt would be DreamWorks’ first traditionally animated feature film.

Simon Wells, who co-directed The Prince of Egypt with Steve Hickner and Brenda Chapman, recalled his initial hesitation about the project during a 1998 interview. “I was thinking, ‘Do I really want to make this story?'” he remembered. “I thought, ‘Are we going to wind up doing a gentle, animated version of this?'”

Wells then thought about a brutal passage from the tale, in which the Egyptian prince Moses, seeing the persecution of the Hebrew slaves, grows so angered he kills an Egyptian guard. “My question to Stephen and Jeffrey was, ‘Is the guard going to die?'” said Wells. “I thought, ‘If Moses does kill the guard. If Moses is going to be a murderer and be responsible for that, then it’s going to be a more interesting movie.'”

Wells then thought about a brutal passage from the tale, in which the Egyptian prince Moses, seeing the persecution of the Hebrew slaves, grows so angered he kills an Egyptian guard. “My question to Stephen and Jeffrey was, ‘Is the guard going to die?'” said Wells. “I thought, ‘If Moses does kill the guard. If Moses is going to be a murderer and be responsible for that, then it’s going to be a more interesting movie.'”

The Prince of Egypt, celebrating its 25th anniversary this year, does not shy away from any aspect of the story, precisely how the filmmakers wanted it.

The late Kelly Asbury, who, along with Lorna Cook, served as head of story for The Prince of Egypt, recalled, in a 1998 interview, a conversation he had with Jeffrey Katzenberg: “He said to me, ‘We’re going to push the envelope here. We can’t make this movie and be true to it without dealing with the issues that are in it.’ There’s no way that you can tell this story truthfully without dealing with those issues. We have slavery, we have genocide, we have murder, we have plagues – all of those things are in the movie, and all of those things are part of the story of Moses.”

The film, an adaptation of the first fourteen chapters of the Book of Exodus, follows Moses, from his days as a newborn, whose mother sets him adrift in a basket on the Nile after the Pharaoh has ordered that each newborn male of a Hebrew slave must die. The babe is rescued by the Queen, who adopts Moses.

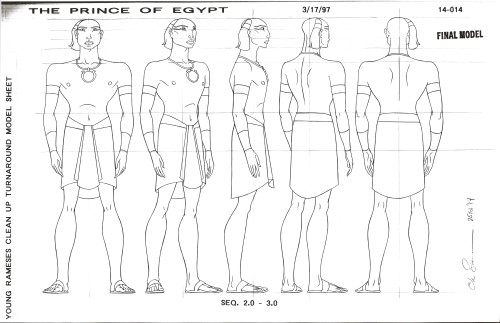

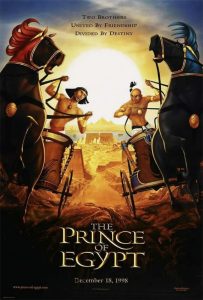

Moses grows up with his brother, Rameses, next in line to inherit the throne from his father, the Pharaoh, Seti. Soon, however, Moses discovers the truth about his heritage as a Hebrew and the brutal power wielded by his father, the Pharaoh.

Moses flees into the Midean desert but finds that God calls him to lead his people out of Egypt and out from under the brutal reign of his brother Rameses.

Moses flees into the Midean desert but finds that God calls him to lead his people out of Egypt and out from under the brutal reign of his brother Rameses.

In re-telling this story, which, as the film’s opening credit states, “…is the backbone of hope and faith for people around the world,” The Prince of Egypt brings iconic moments to life with stunning artistry.

Moses learns the truth about his past through a dream, an incredible creative sequence where hieroglyphics come to life; the burning bush, where God first speaks to Moses, is a compelling moment, with minimal animation, making it even more effective, and the parting of the Red Sea (one of film’s most famous scenes, thanks to Cecil B. DeMille’s 1956 epic The Ten Commandments) is a tour-de-force of effects animation.

“That [scene] was the icon of our parents’ generation when the film came out in ’56,” said co-director Hickner in 1998. “We knew we had to come up with the icon for our generation.”

In addition to such memorable moments, The Prince of Egypt also boasted a voice cast that seemed to employ almost every actor working in Hollywood, including Val Kilmer as Moses, Ralph Fiennes as Rameses, Michelle Pfeiffer as Moses’ wife, Tzipporah, Sandra Bullock as Miriam, Moses sister, Jeff Goldblum, as his brother Aaron, Patrick Stewart as Pharoah Seti, Helen Mirren as the Queen, Danny Glover as Jethro, Tzipporah’s father, and Steve Martin and Martin Short as the high priests, Hotep and Huy.

In addition to such memorable moments, The Prince of Egypt also boasted a voice cast that seemed to employ almost every actor working in Hollywood, including Val Kilmer as Moses, Ralph Fiennes as Rameses, Michelle Pfeiffer as Moses’ wife, Tzipporah, Sandra Bullock as Miriam, Moses sister, Jeff Goldblum, as his brother Aaron, Patrick Stewart as Pharoah Seti, Helen Mirren as the Queen, Danny Glover as Jethro, Tzipporah’s father, and Steve Martin and Martin Short as the high priests, Hotep and Huy.

The two priests have a musical number which is “Playing with the Big Boys,” one of six songs in the film from Stephen Schwartz, who would go on to write the music and lyrics for the Broadway blockbuster, Wicked, and had also helped create the songs for Disney’s Pocahontas (1995) and The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996) (the underscore for Prince of Egypt is from Hans Zimmer).

The other songs in the film include the gripping opening number “Deliver Us,” “All I Ever Wanted,” sung early in the film, first by Moses and then the Queen, “Through Heaven’s Eyes,” sung by Jethro, after Moses has come to the Midean tribe, “The Plagues,” and “When You Believe,” which serves as the anthem for the Hebrews exodus. It was also a Billboard Top 40 hit, sung by Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey, and also went on to win the Best Original Song Oscar).

The Prince of Egypt looked to break the more conventional animated musical formula. “The subject matter just needed something more classical than Broadway,” added co-director Chapman (the first female director of a major studio animated feature) in a 1998 interview. “It needed to feel epic. We all felt that stopping for a number would be a little strange. It had to have the same feel as the rest of the movie.”

The Prince of Egypt looked to break the more conventional animated musical formula. “The subject matter just needed something more classical than Broadway,” added co-director Chapman (the first female director of a major studio animated feature) in a 1998 interview. “It needed to feel epic. We all felt that stopping for a number would be a little strange. It had to have the same feel as the rest of the movie.”

Schwartz, who crafted both lyrics and music for the film’s songs, said, just before the film’s release, that the songs were “more about trying to find a sound that would be accessible to American audiences, but would still immediately suggest the film’s geographical location, clearly that it would sound Egyptian, that it would sound Hebraic, but not Fiddler on the Roof-type Jewish music.”

Schwartz also stated, “One of the really enjoyable things about the animation process is the collaborations with the visual artists. That’s something that’s particular to this medium.”

The Prince of Egypt opened on December 18, 1998, with tremendous publicity and marketing. Critics responded to how daring the film is; Roger Ebert noted, “This is a film that shows animation growing up and embracing more complex themes, instead of chaining itself in the category of children’s entertainment.”

Twenty-five years later, Mr. Ebert’s words still stand as a perfect description of The Prince of Egypt, a powerful film from animation’s renaissance period, with stunning work from artists who pushed the boundaries of the medium.

Michael Lyons is a freelance writer, specializing in film, television, and pop culture. He is the author of the book, Drawn to Greatness: Disney’s Animation Renaissance, which chronicles the amazing growth at the Disney animation studio in the 1990s. In addition to Animation Scoop and Cartoon Research, he has contributed to Remind Magazine, Cinefantastique, Animation World Network and Disney Magazine. He also writes a blog, Screen Saver: A Retro Review of TV Shows and Movies of Yesteryear and his interviews with a number of animation legends have been featured in several volumes of the books, Walt’s People. You can visit Michael’s web site Words From Lyons at:

Michael Lyons is a freelance writer, specializing in film, television, and pop culture. He is the author of the book, Drawn to Greatness: Disney’s Animation Renaissance, which chronicles the amazing growth at the Disney animation studio in the 1990s. In addition to Animation Scoop and Cartoon Research, he has contributed to Remind Magazine, Cinefantastique, Animation World Network and Disney Magazine. He also writes a blog, Screen Saver: A Retro Review of TV Shows and Movies of Yesteryear and his interviews with a number of animation legends have been featured in several volumes of the books, Walt’s People. You can visit Michael’s web site Words From Lyons at:

Are you embracing Roger Ebert for saying “animation … (is) .. children’s entertainment”?

Maybe that’s not what you meant ..but …

(The “critic” who believes “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls” is the perfect screenplay)

You left out the word “chaining itself” when you referenced Roger Ebert. I took that to mean that all animation was being unfairly labeled as children’s entertainment. I don’t want to speak for Mr Ebert, but that’s how I interpreted that, and, no, I don’t think animation should be thought of that way.

As for “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls,” I will comment on that when the animated re-make debuts. 🙂

Ebert would call “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls” a perfect screenplay. After all, he WROTE it!

I haven’t seen anything that indicates Ebert was ashamed of his BtVotD screenplay, but I haven’t seen anything suggesting he thought it was “perfect”, either. It could very easily be that he considered it less than “good”, while still sufficient for a campy, over the top exploitation movie. That sort of thing is very much not my cup of tea and I have little doubt I would hate it, but without seeing it I’m not qualified to judge the quality of its writing.

As for his opinions on animation, he gave good reviews to Ghost in the Shell, Tokyo Godfathers, Coonskin, and Waltz with Bashir, among others, so he was well aware that animation could be used for stories aimed at adults. In writing “This is a film that shows animation growing up and embracing more complex themes, instead of chaining itself in the category of children’s entertainment.”, he was, like many animation fans and critics, bemoaning the fact that mainstream American animation producers had been focused almost exclusively on children’s and family films.

This is really the kind of movie that can only exist when you have someone who has such a grudge against his former employer [and is backed up by two other guys with deep pockets]. It’s fascinating how this stands alone in Dreamworks Animation’s catalog, even in their brief era of traditional animation. I notice Katzenberg loooved the shifty, snarky male protagonist and his contentious relationship with the rebellious woman… not even this movie is completely safe from that dynamic [they even try to shove it into Spirit, the movie with mostly silent horses], but it’s definitely less obnoxious here than in Sinbad.

In any case, this is such a strong first outing from the studio that DWA justified their ability to just do whatever the hell they want. I imagine that wasn’t a luxury Disney artists felt they had at that time.

People who are unfamiliar with the Bible often assume that it is full of Holier-Than-Thou platitudes and sweet, innocent stories with no connection to reality. When in truth the Bible contains adult material that could shock, disturb, and startle modern audiences. Human frailties and foibles are revealed in stark detail. Those who are into censorship would find plenty of material for their objections. It is often referred to as The Good Book, but many of the persons and situations depicted therein are anything but good. For my money, it is as relevant today as it has ever been.

It is highly commendable that Katzenberg and his crew chose not to sugarcoat the story of Moses but to present it as in the Bible–incorporating some historical and traditional supplements (such as his life in the Egyptian royal household, which only receives brief mention in the Scriptures). The killing of the Egyptian guard is handled with taste. It is also memorable when the waters of the Nile turn to blood. My favorite scene in the film is the one of the Passover. The songs seem to underscore and supplement the story very effectively, as do the voice artists, none of whom seems to be self-promoting, but instead using their talents to evoke memorable and iconic characters that support the telling of the story. (Evidenced by the fact that several of the actors do not sound at first like their usual screen personas, but rather as more like the character they are depicting–unlike other films that have used celebrity voices in a more exploitive manner.) Cartoony elements and cute little animal sidekicks are downplayed, which is as it should be. The film has a mature tone and quality to it.

Dreamworks should be commended for crafting such an intelligent and accessible interpretation of a centuries-old and highly iconic story. While comparisons to the classic film “The Ten Commandments” are inevitable, covering as it does so much of the same territory, still “The Prince of Egypt” stands on its own as a remarkable achievement in its own right. (Also worth a look is the later Dreamworks animated Biblical film “Joseph: King of Dreams.”)

The most mature take on the Bible in animation was an HBO series called Testament, even though it went too far with its gore on many occasions.

I agree; Moses is by far the most complex of the Biblical figures.

Agreed! Most people have an erroneous conception about the stories of the Bible to the point they seem to talk down to the general public about the scriptures. In this censorship happy era, there’s no way major studios would allow an animated film like The Prince of Egypt to be made, especially how it so eloquently depicted Moses’ story. And like you pin pointed, Frederick, the actors portrayed their roles without making the film about them, but that they were contributing to the story that was being told, something that is important to any depiction of the Bible.

Moses looks like a transgendered Pocahontas. And I’d love to know what Stephen Schwartz means by that “‘Fiddler on the Roof’-type Jewish music” crack. As opposed to “Godspell”-type Jewish music?

Footnote: In recent years “Prince of Egypt” was adapted into a stage musical.

…That found immense acclaim from the West End crowd, but has yet to hit Broadway.

I just saw this a few months ago as part of this year’s Columbus Cartoon Crossroads event with a live Q & A presentation with Brenda Chapman at the end. I was pretty impress with this and thought Hans Zimmer did a great job with the soundtrack.

My personal thoughts on Katzenberg aside, I’d say it was for the best that he made this movie one of the first from DreamWorks. At Disney, it was his idea for “Pocahontas” and “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” to be all dark and “preachy” to repeat the success “Beauty and the Beast” had at the Oscars, he nearly killed “Toy Story” with his push for mean-spirited characters, and he championed “Runaway Brain” when the other execs were antsy what it was doing to their Mouse. With a studio all his own and no pre-established brands to consider, “The Prince of Egypt” was a perfect chance to establish DreamWorks as a quality yet “sophisticated” alternative to what Disney was putting out.

Runaway Brain was certainly a daring tour-de-force!