This is Part 2 of Jim Korkis’ 1984 interview with Disney Legend Jack Hannah. For part 1 – CLICK HERE.

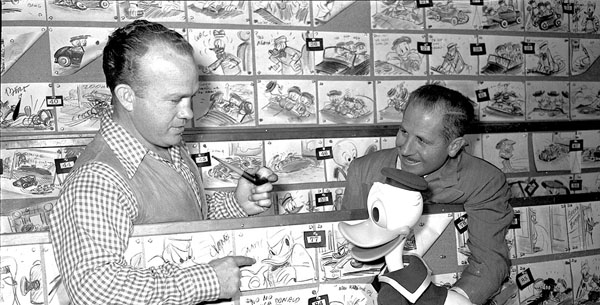

Jack Hannah (left) and Donald’s voice, Clarence Nash (right)

Korkis: How did the team of Barks and Hannah drift apart?

Hannah: The Studio was gearing up for the war. You’ll notice in my story credits an awful lot of cartoons with army themes, using Pete as the sergeant and the Duck as the dumb recruit. They gave Jack King a picture about a housewife saving fat for the war effort. [Out of the Frying Pan, Into the Firing Lane] I don’t know why people were supposed to save grease. Maybe it was to make the enemy slip on it.

Anyway, Jack King wasn’t interested in the mechanical part of the picture, showing all these cooking fats going down a funnel. So he gave me a little section to direct, and I loved it, just being able to do something. That was my first piece of direction. At this time, I had to go to Wisconsin on family business. When I returned to the Studio, Carl had quite and become a comic book artist.

“Out Of The Frying Pan Into The Firing Line” (1942)

Korkis: Did it seem strange that Barks would leave?

Hannah: Carl had done a lot of magazine work before he came to the Studio, although he never discussed it. I think he liked that kind of work and was getting sick of the regimented work he had to do at the Studio. There it was always teamwork, and Carl was an individual. He seemed more comfortable working alone: Carl Barks had to be Carl Barks. He couldn’t sit down and share ideas in a story as easily as some people could.

In fact, I don’t think Carl really started to shine until he moved over to comic books. I feel he liked the work better because he was his own boss and could express himself any way he wanted. While he was in animation, he had to keep in mind what could reasonably be animated. To draw acres of money for one panel of a comic book is one thing. To draw twenty-four pictures of it for one second of animation would be quite another job.

Also, in animation, Carl found that his stuff was changed around, because it had to go through so many people: the head of the story department, the director, and the animators. He had to adapt to the visions of half a dozen different guys. In comic books, he could do things exactly the way he wanted to.

Korkis: What happened to you after the war?

Hannah: I went back to being a storyman, but without Carl, I felt kind of lost. Then Hal Adelquist, who was now head of the story department, asked me if I would help Bill Berg, a young storyman who was struggling with a script. I filled it with a lot of personality bits, which I always believed were more important in a story than simple gals.

Then I went to Hal and said, “I’d just love to direct this. As much as I like Jack King, I can’t see him directing these personality sequences.” I asked repeatedly and finally the word came back from Walt. I supect that what he said was, “Go ahead; let him hang himself.”

I got a secretary, got an assistant, and started directing. I met Walt in the hall one day, and he asked, “How’s it going?” I replied, “Fine, but if I don’t get started on another cartoon, I’ll have to put all my costs on this picture, and it’s going to run over budget. I need another short to start on while this one is going through production.”

I got a secretary, got an assistant, and started directing. I met Walt in the hall one day, and he asked, “How’s it going?” I replied, “Fine, but if I don’t get started on another cartoon, I’ll have to put all my costs on this picture, and it’s going to run over budget. I need another short to start on while this one is going through production.”

I’m certain that Walt had looked at that short either at home or in a projection room, because I knew him better than to believe that he’d just take my word for it. The next thing I knew, Adelquist came and told me that Walt had said it was okay for me to direct another short. So I picked another short and ended up directing cartoons for the next seventeen years. That first short I directed was Donald’s Off Day (1944).

Korkis: How has the animated Donald changed over the years?

Hannah: I had little do with the earliest stages of his development. As I remember, he was drawn with a pointed beak and gangling arms and legs. By the time I got into close contact with him, his anatomy had changed gradually into rounder, cuter shapes. Animator Fred Spencer had a lot to do with the change-over. I’m not sure that some of Donald’s character wasn’t lost in this drawing change.

Of course, every artist drew every character slightly differently, even with the model sheets which were made in an attempt to avoid this. That’s one of the big problems of animation: keeping the animators drawing the character the same. Some of them drew him with a bigger head, some more pear-shaped. The thing was to ensure that the audience didn’t notice.

Korkis: What were some of the changes that took place in the Duck shorts when you became a director?

Hannah: For one thing, we began looking for foils for the Duck. His three nephews were always available, and somebody had come up with the idea that it would be clever to have them say one line of dialogue with all three sharing the sentence. One nephew would say the first two words, the next would say the middle of the sentence, and the third would finish it up.

I put a stop to this, because it ruined all sense of timing. You couldn’t carry through a gag. You’d have to stop and wait for each nephew to say his lines, and it became hard to incorporate the dialogue into the action.

Even though Donald and his nephews worked well together, we needed variety in our material, so we tried a variety of characters. The Aracuan bird who was introduced in The Three Caballeros was one of our first attempts. Then we did a series with a beetle named Bootle Beetle. Working with these other characters led up to the creation of Chip ‘n’ Dale, the two impish chipmunks. I also developed Humphrey the Bear.

Even though Donald and his nephews worked well together, we needed variety in our material, so we tried a variety of characters. The Aracuan bird who was introduced in The Three Caballeros was one of our first attempts. Then we did a series with a beetle named Bootle Beetle. Working with these other characters led up to the creation of Chip ‘n’ Dale, the two impish chipmunks. I also developed Humphrey the Bear.

Korkis: Why did you eliminate the angry arm-pumping that Donald did in the earlier cartoons?

Hannah: It had outlived its humor as far as most of us were concerned. I think an animator first created that bit where Donald hops up and down with one arm outstretched. [Dick Lundy.] I got tired of putting the Duck through tantrum attacks for no reason.

Korkis: Did you have any special way of telling the nephews apart?

Hannah: They were all considered the same character, interchangeable. Each acted the same, and we never really thought of them as individuals.

Korkis: Why was Scrooge McDuck never used in a short?

Hannah: We did consider using Scrooge for a short, while I was a director, but the idea was shot down because someone voiced strong feelings that a character who went wild over money wasn’t funny. Scrooge’s greed was the reason we didn’t use him.

Of course, this all happened at a time when we were stopping production on the shorts, so that ended any further discussion. I understand that a short was made later using the character [Scrooge McDuck and Money], but I was not at the Studio at the time.

Korkis: You directed the 1952 Duck short Trick or Treat. Did you have any say about the comic book version that Barks drew?

Korkis: You directed the 1952 Duck short Trick or Treat. Did you have any say about the comic book version that Barks drew?

Hannah: I didn’t even know that Carl had done a comic book version of it. I saw a painting he did on that subject a couple of years ago, but I’ve never seen the comic. There was no coordination between the animation department and the comic book department.

Korkis: What was the biggest problem with directing Donald Duck?

Hannah: The voice! The bane of my life was getting anybody to understand the Duck. It was aggravating as hell to do a picture with dialogue and not be able to understand the main character. But he did have a variety of moods, and you could use strong poses to convey what he was trying to say.

Korkis: Did you work on any Donald Duck cartoons that were not finished?

Hannah: Yes. If a story wasn’t developing, the storymen would shelve it before it was presented to a director. That happened with Carl and me a couple of times. However, there was one time when I was directing a short that we got as far as the animation before junking the entire thing. Donald was working with some small animal like a baby elephant. Strangely enough, it wasn’t the Duck’s voice that caused the problem this time, but the other character’s voice. A young guy came in to do it, and he was just terrible.

Korkis: Did you ever use rotoscoping, the method of filming live action as a reference for animation?

Hannah: Once, in 1951. You know the girls in Dude Duck? Bill Justice animated those girls using the rotoscope, but only as a guide. We had a set built and filmed the girls as they left the bus and ran toward the camera. We didn’t really need to do it that way, but it gave us a chance to look at girls in sweaters.

from “Dude Duck”

Hannah: I didn’t feel that the Duck could ever work into a feature-length picture. I think you’d go crazy trying to understand him over the period of time that a feature takes. Also, he was not a strong enough character to carry a feature. I think he would work fine in shorter sequences, like the one Mickey Mouse did as the Sorcerer’s Apprentice in Fantasia.

Korkis: How did you begin directing the Duck for television?

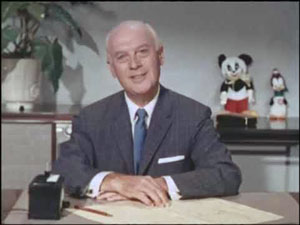

Hannah: In the 1950s, the shorts were becoming too expensive to make, running from $90,000 to $100,000 for a seven-minute short. As a result, Walt couldn’t make his money back on a new short for several years. He switched me over to the Disneyland television show we were developing for ABC, and I ended up directing fourteen hour-long shows, most of them with Walt at his desk talking to Donald.

On the first show, live-action directors were hired to direct the action, but Walt sensed they couldn’t feel the presence of unseen animated characters. So he had me join the Directors Guild. One of the big problems was the camera operator couldn’t get used to the idea that there was another actor there and would frame the picture wrong. Eventually, we had to use a cardboard cutout of Donald to make everyone happy.

Korkis: Why did you leave the Disney Studio in 1959?

Hannah: The TV show was leaning more toward live action, and less emphasis was being put on cartoon programs. Walt had me pegged as a cartoon director, so he balked at the suggestion of my going into live action. At this time, Walter Lantz offered me a job heading up his animation department, and I took it.

Hannah: The TV show was leaning more toward live action, and less emphasis was being put on cartoon programs. Walt had me pegged as a cartoon director, so he balked at the suggestion of my going into live action. At this time, Walter Lantz offered me a job heading up his animation department, and I took it.

I directed several shorts for Lantz, as well as the live action lead-ins for The Woody Woodpecker Show. But no other studio was able to give animation the time and effort required to match Disney quality, because of the cost. Finally, I felt that the challenge was no longer there for me.

I had taken up landscape painting while working at Disney’s, and I was getting so professional at it that I thought I could make a living at it. So I painted in oils for several years, and my work spread out into galleries throughout the western states.

Korkis: Have you seen any of Barks’ paintings?

Hannah: I’ve seen his Duck paintings. I was amazed that, in the drawing and ideas, he was able to incorporate everything that was Carl Barks. I was also very impressed by the coloring.

His wife Garé is also a fine painter. That’s how Carl and I got back in touch after all those years: Garé was being exhibited in a gallery that was featuring some of my stuff. In some ways, I feel that Carl and I are even better friends now than we were working together in the story department.

Korkis: You eventually went back to Disney’s?

Hannah: In the early 1960s, Walt invited me back to the Studio to be a story consultant on live-action films. He had been complaining that they hadn’t been getting enough cartoon ideas into their live action. The so-called comedy writers were way too straight for Walt, so I came in three days a week to help “plus” a script. I was working on a film called Rascal when Walt died at the hospital across the street from the Studio.

Hannah: In the early 1960s, Walt invited me back to the Studio to be a story consultant on live-action films. He had been complaining that they hadn’t been getting enough cartoon ideas into their live action. The so-called comedy writers were way too straight for Walt, so I came in three days a week to help “plus” a script. I was working on a film called Rascal when Walt died at the hospital across the street from the Studio.

Shortly afterwards, I left the Studio; but in 1975, they called and asked me to head a program of character animation at the California Institute of the Arts, a school Walt built and funded through money from the Disney Foundation. I taught there until June 1983. Then I resigned so that I could have more time to work on my painting.

Korkis: How would you describe Donald Duck?

Hannah: He was a lovable twerp who could never stay out of trouble, which he usually brought on himself. For instance, if he came across a bee gathering honey, Donald would slyly place an obstacle in the bee’s path and enjoy the pee’s discomfort. When his prank backfired, he would lose his famous temper.

He was a comic villain. That’s probably the best way to describe him: villainous, but in a mild way. He just wanted to get the best of somebody or something, but never did. His motive was never really vicious, and you could forgive him because the other guy always won out.

Korkis: Any final thoughts on Carl Barks?

Hannah: I would describe Carl Barks in two words: imaginative and prolific. He worked very hard and remained his own man. I learned a great deal from working with him.

Many of the top pros I worked with are gone now. It’s funny, though: nobody ever seems old in this business. Certainly not Carl.

Korkis: Any final thoughts on Jack Hannah?

Hannah: I’m very comfortable now. I don’t believe that what I think of my work means a hell of a lot; it’s what the audience thinks that counts. That’s what I’ve tried to teach my students.

Panels by Jack Hannah

THAD KOMOROWSKI is a writer, journalist, film restorationist and author of the acclaimed (and recently revised) Sick Little Monkeys: The Unauthorized Ren & Stimpy Story. He blogs at

THAD KOMOROWSKI is a writer, journalist, film restorationist and author of the acclaimed (and recently revised) Sick Little Monkeys: The Unauthorized Ren & Stimpy Story. He blogs at

The publicity poster for “Donald’s Off Day” does not bear any resemblance to the content of the finished cartoon. I’m only guessing that this might have been an earlier concept for the short? As it is one of the more unusual of the Donald Duck cartoons, perhaps it went through numerous story changes. (Unusual because it keeps its focus on Donald’s one objective–to play golf–and provides a glimpse of his domestic life with his three nephews. And despite his wanting to play golf, he never once makes it to the golf course).

The hour-long shows featuring Donald Duck are often cleverly-woven narratives combining several related shorts with new animated sequences linking them. One of the best of these (directed by Hannah, perhaps?) is “Donald’s Weekend,” which brings Huey, Dewey, and Louie on a weekend visit to their uncle and threads together cartoons such as “Early to Bed,” “Donald’s Off Day,” and “Donald’s Golf Game” among others. The latter two cartoons are linked together by animation that adds one more coda to the conclusion of “Off Day” so that the sun comes out and Donald can play golf after all and also sets up the gag in “Golf Game” involving the joke golf clubs that HDL give to Donald later on. It’s too bad these hour long episodes are not widely available, as they are very entertaining, and it’s fun to see the shorter cartoons given a wider context.

Jack Hannah was right: having Donald’s nephews divide each line of dialogue up among themselves didn’t really work. Popeye’s identical nephews had the same mannerism: “We!” “Don’t!” “Like!” “Spinach!” Apparently no one ever thought to tweak the formula by having one nephew utter funny non-sequiturs. But the ducks’ voices would have tended to work against that.

I’m sure the experience of ogling a bevy of bouncing cowgirls in sweaters was very enjoyable for Hannah and Bill Justice, but the rotoscoping clashes with the style of the cartoon. I wish they had assigned that scene to Freddie Moore, who could have showed them how cartoon cowgirls in sweaters are supposed to bounce.

That’s Billy Mumy on the “Rascal” poster. It was his first starring role after “Lost in Space” was cancelled.

…and where, oh where, is Nash’s famous and iconic Donald ventriloquist figure TODAY, I wonder??

Nice job, Thad! I’m sure Jim would appreciate it. (I sure did!)

In regards to the short Out of the Frying Pan, Into the Firing Line, grease was saved during WW-2 as the fat could be processed into glycerin which was used in building bombs.

Jim Korkis sure knocked this interview out of the park! That said, Jack Hannah’s bit here really struck me:

“He was a comic villain. That’s probably the best way to describe him: villainous, but in a mild way.”

Personally, this viewpoint is part of why his handling of Donald doesn’t gel with me half the time. It even got to the point where in Donald’s Award (1957 Disney Anthology episode), even PETE was portrayed in a more sympathetic light than Donald.

Anyway, to focus on the positives, the Donald shorts of his I liked were the ones directed up until 1947’s Clown of the Jungle, the nephews shorts (including even after 1947) and 1953’s New Neighbor. Humphrey the Bear was also gold, but I mention this separately since Donald notably takes the back seat in the shorts featuring the former.

A comic foil might be a better term which I think is what Jack meant. If I recall, there were a few Barks comics that made the duck a foil for his nephews (right before the introduction of Uncle Scrooge).