I was deeply saddened by Jim Korkis’ passing earlier this year. In the seventeen or so years I knew him, he struck me as one of the most positive and generous people in the animation historian business. It was a quality all Cartoon Research readers experienced year in and year out thanks to all his wonderful columns.

Jack Hannah

If you can track down copies of Jim’s interviews, do it. They’re scattered all over, but all worth seeking, many of them in Didier Ghez’s wonderful Walt’s People series. One of my absolute favorites is an oral history of sorts made up from his interviews with Disney Legend Jack Hannah that he did for The Carl Barks Library Set I released by Another Rainbow in 1984. (There’s a short piece about how important Hannah was to Jim and his career as a Disney historian over here).

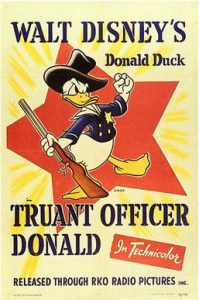

The primary focus was about the years Hannah collaborated with Barks, mostly when they were a writing team for a string of memorable animated Donald Duck cartoons, many of which developed Huey, Dewey, and Louie (Donald’s Nephews, Donald’s Cousin Gus, Fire Chief, Window Cleaners, Timber, Truant Officer Donald, Trombone Trouble).

The interview speaks volumes of both Hannah and Jim. Speaking as someone who’s had to do it, it isn’t an easy feat getting artists to talk about someone else’s work. Hannah here is secure enough in his own place in cartoon history to talk about someone else who had far eclipsed himself (with or without Donald Duck), and Jim is able to pull it all off.

The interview speaks volumes of both Hannah and Jim. Speaking as someone who’s had to do it, it isn’t an easy feat getting artists to talk about someone else’s work. Hannah here is secure enough in his own place in cartoon history to talk about someone else who had far eclipsed himself (with or without Donald Duck), and Jim is able to pull it all off.

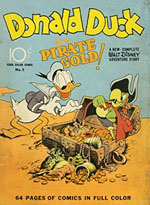

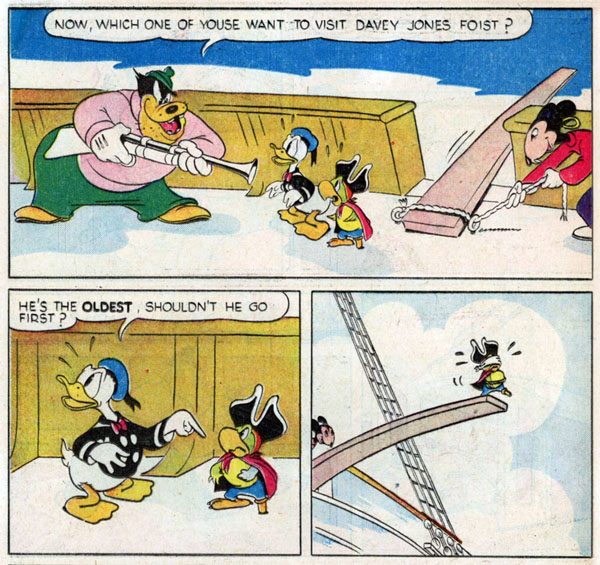

This piece probably wasn’t an easy sale to Barks-absorbed scholars either, but I’m sure the fact that Hannah drew the other half of the first Donald comic book story with Barks art, “Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold” (more or less helping start Barks on his legendary way), and that the piece would appear alongside it, made it too senseless to not include.

As I was getting this ready, I realized nowhere in the interview did they mention that Hannah actually drew a remake of “Pirate Gold”, retitled “Donald Duck and the Pirates” for a 1947 giveaway comic. It was the first of several such remakes (one with the characters from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and one with those from Peter Pan). “Pirate Gold” isn’t great shakes as a comic book story (the behind-the-scenes tale of it spawning from an aborted feature with Mickey, Donald, and Goofy is far more interesting), but the fact that Western went to that well so often is a testament to the story’s endurability and the immense fondness cartoonists have for that seminal Duck comic. It helped spawn a comic empire, and Hannah’s role in that should never be forgotten.

So here you go: the entirety of that Hannah-Barks piece by Jim transcribed (with a few select illustrations). I’m sure Jim would more than approve of its appearance here.

The Other Duck Man

An Interview with Jack Hannah by Jim Korkis

Most fans of Carl Barks know Jack Hannah only as the other half of the team that drew “Pirate Gold,” but the professional association between these two artists predates that comic book by several years. They met in 1939, shortly after Hannah joined the Walt Disney Studio’s story department, and were soon teamed to work on the Donald Duck animated cartoons. Since Hannah had just spent five years as a Disney animator and Barks had spent four as a storyman, the combination of talents could hardly have been better.

The two men worked closely together in the story department until 1942, when Barks left the Studio to draw comics for Western Publishing. Although he and Hannah were mostly out of touch in the years that followed, their respective careers left parallel wakes in the Disney duckpond. During the years that Barks was writing and drawing the adventures of Donald and his Uncle Scrooge, Hannah went on to become the principal animation director for the Duck cartoons.

He was born John Frederick Hannah in Nogales, Arizona, on January 5, 1913. After attending grammar school in San Ysidro and high school in National City, California, he moved to Los Angeles in 1931 to take an art course at the Art Guild Academy there. His first commercial artwork consisted of poster designs for various Hollywood theaters and for the advertising firm of Foster and Kleiser.

Hannah joined the Walt Disney studio in January 1933 and spent almost three decades there animating, writing, and directing Donald Duck cartoons. He left the Studio in 1959 but returned from time to time in the 1960s to work on scripts for Disney’s live-action films. In 1975, the Studio asked him to take charge of the School of Character Animation at the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia. He remained at the Institute until June 1983, when he resigned his post in order to devote more time to painting. Hannah is a skilled landscape artist, and his oils are displayed in galleries throughout the West.

In the following interview, Hannah recalls his Disney years and reminisces about working with Carl Barks. The interview is a compilation of several conducted by Jim Korkis from 1977 to 1983. “During those years,” Korkis comments, “my respect and affection for Jack have continued to increase. There is an energy about him that belies his age. His eyes still twinkle with mischief, and his voice is clear and without hesitation.”

“When he moves from his chair to illustrate a point of animation, his body and face are as fluid as those of any character he has drawn or directed. He still moves with the grace of a professional fighter, an occupation that earned him a Golden Gloves competition before he entered animation. In fact, one Disney wag used to say that Hannah was the only man he ever met who went from canvas to canvas.”

Jim Korkis: How did you come to join the Disney Studio?

Jim Korkis: How did you come to join the Disney Studio?

Jack Hannah: During the depression, I was seeking work in the commercial art field. I went into an agency with my portfolio, and the guy there who looked at my work said, “Why don’t you try Walt Disney?” I replied that I wasn’t a cartoonist but a commercial artist, but he kept insisting. With fear in my heart, I went out to the Disney Studio and turned in my portfolio.

I waited for about a week or two and was finally called by Ben Sharpsteen, who at that time was reviewing incoming talent. He asked me to come in for a two-week tryout. Well, that two-week tryout ended up in thirty years of work at Disney’s.

Korkis: What was some of your first work there?

Hannah: I started at the Sutdio as an inbetweener on January 31, 1933, and found myself working on Three Little Pigs and several other shorts. I had just turned twenty and I don’t think now that I was mature enough to grasp the real meaning of animation. I tore into it like any young buck without really thinking too much. It was all pretty exciting, and I guess I was well thought of, because I was moved from inbetweener to assistant animator very quickly.

I assisted such outstanding animators as Norm Ferguson, Dick Huemer, Dick Lundy, Ham Luske, and Les Clark. I would clean up all of their animation, and usually they would give me a scene or two to animate on my own.

Korkis: When did you start animating on the Donald Duck shorts?

Hannah: While I was working as an assistant, Jack King joined the Studio. He was assigned to work on a new series of shorts to feature the Duck, and I was picked to join his crew as a full-fledged animator. The Duck had become more and more popular, and his temper made him easier to work with than Mickey Mouse. I remember many stories were started with Mickey, but as soon as the writers began to rough the Mouse up, somebody would say, “That’s more of a Donald Duck story.”

Mickey was more the hero type, so it was harder to find material for him. Walt had a special love for Mickey, and I don’t think he wanted to see Mickey roughed up. I consider my animation on the Duck somewhere in the middle.

Korkis: When did you move over to the story department?

Korkis: When did you move over to the story department?

Hannah: In 1939. Walt would send out copies of the scripts of new pictures under consideration, and all the staff would turn in gags. We’d be paid anywhere from $2.50 to $5.00 if a gag was used. This was good spending money on the side. I had turned in lots of these gags, and Harry Reeves, who was in charge of the story department, invited me to transfer over. At this time, Snow White excitement was stirring up the Studio, and several middle of the roaders like myself were moved aside to make room for some of the fresh animation talent that Walt brought in.

Korkis: Were you immediately teamed with Carl Barks?

Hannah: I hadn’t even met him yet, though I had been animating Jack King’s Donald Duck shorts, for which Carl had done some writing. The animation department and the story department didn’t get together much in those days. When I was assigned to the story department, I rotated around a bit, working with several different storymen.

By this time, Carl was considered a Duck man, because he had done a lot of story work on Donald. The fact that I had just been animating the Duck may have been a reason they thought of putting Carl and me together. When we moved to the new studio in Burbank, it was announced that Carl and I were to be an official storyteam exclusively for Jack King.

Korkis: How did you and Barks go about developing a Duck story?

Korkis: How did you and Barks go about developing a Duck story?

Hannah: We’d talk over possible story situations and even go get story springboards from the Sears and Roebuck catalog. One time we saw a picture of a steam shovel that stuck in our minds. I used it later in a Chip ‘n’ Dale short I directed.

When we had an idea, we’d try to work on a story around it. We’d break up the story into sections, and each of us would work up some gags and put them up on the storyboard. At certain points, we’d call in two or three other groups for gag sessions. Those sessions involved real teamwork, with everyone proposing ideas.

Korkis: Did Walt Disney ever attend these meetings?

Hannah: Many times. He was very outgoing, and that encourage all of us to see things differently, to get wild and take chances. But he was an entirely different person away from animation, more suave and reserved, like a businessman. However, when he got into the workshop, he was a workman.

He could be brutal at times, building you up and then pulling the rug out from under you! He’d start the idea for a sequence of gags — or we would — and we’d build on it. He’d get us feeling really excited, and we’d say, “That’s great, Walt!” Suddenly his whole mood would change, and he’d reply, “Naah, we aren’t going to do that.” That type of thing happened many times.

[Barks comments: “Jack had several more years of experience with Walt’s story meetings than I had. I agree that in the years I was in such meetings Walt could be very frustrating and could scare me to death with a flick of his eyebrows. As for being brutal, I didn’t see much of that in the early years of the Duck shorts, though I noticed an increasing shortness of fuse by 1941, when too many feature projects and financial worries and the impending World War got to overcrowding his patience.”]

Korkis: Was Jack King actively involved in these meetings?

Hannah: King never gave us any input while were working on a story. He’d stop in to say good morning or something like that. King was a good director in the sense that he’d put on the screen exactly what you had on the storyboards, but he wasn’t a strong storyman and very seldom added things. This often irritated both Carl and me. We saw a lot of potential in the basic ideas we came up with. Then, when they were animated, they fell short, because the director did not explore their possibilities. This frustration was one of the reasons I wanted to become a director myself.

Korkis: Did you have any problems working with Barks?

Hannah: I loved working with him and learned a lot from him. He was older and more grown-up than I was. When we weren’t working together on a story, I’d spend my time in the Studio commissary having a Coke and checking out the waitresses, but he’d still be back at his desk working away. Carl was a real workhorse.

He was more than just a gagman. He was interested in the overall theme and made sure that the gags helped develop the story and weren’t just thrown in for an easy laugh that might have broken the story’s rhythm. Frank Tashlin, with whom I worked on several stories, was completely different. He could recall every gag he ever heard and had a store of the stuff in his head. He’d write on a storyboard like mad. But everything Carl Barks came up with had to be original and had to tie into the story. He didn’t rely on a stockpile of gags. This whole approach to story influenced my later directing efforts.

He was more than just a gagman. He was interested in the overall theme and made sure that the gags helped develop the story and weren’t just thrown in for an easy laugh that might have broken the story’s rhythm. Frank Tashlin, with whom I worked on several stories, was completely different. He could recall every gag he ever heard and had a store of the stuff in his head. He’d write on a storyboard like mad. But everything Carl Barks came up with had to be original and had to tie into the story. He didn’t rely on a stockpile of gags. This whole approach to story influenced my later directing efforts.

Korkis: Is there a particular Barks gag that sticks out in your mind?

Hannah: For Truant Officer Donald, Carl came up with the idea of having Donald find three roast chickens with the nephews’ hats on and think that he had killed Huey, Dewey, and Louie. That idea sparked my idea of having one of the nephews come down on a rope dressed as an angel. Harry Reeves hated that sequence. He thought it was too gruesome, and Carl and I really had to fight for it. Later, when the cartoon was previewed, it got a big laugh, so we were proven right.

It’s a good example of how two storymen can work together. Carl would come up with an idea that would spark another one from me; that in turn would spark another idea from Carl. That particular story just seemed to flow out of us. It wasn’t always that smooth. Sometimes we’d go through three or four story ideas until one caught hold and started to develop itself. Then all we’d have to do was help it along.

Korkis: What do you recall of Timber?

Korkis: What do you recall of Timber?

Hannah: We worked especially closely on that one, and I enjoyed doing the story very much. The scene where Donald picks up the dynamite on Black Pete’s table still sticks out in my mind. We wanted that sequence done without music, just the ticking of the clock to build suspense. But the director felt differently and added lots of music at that point. I felt the scene wasn’t as effective that way.

Korkis: Your own work on the Timber storyboards is more detailed than Barks’. Was there a reason for that?

Hannah: It’s a difference of style, just as two painters will communicate the same idea differently. We had our individuals way of sketching the story, and both ways seemed to get the job done. Even then I had an interest in directing, so I may subconsciously have paid more attention to shading or detail simply because I wanted to get the idea across to the director as clearly as possible.

Korkis: What did Disney think of the team of Barks and Hannah?

Hannah: We were a story team for quite a while, so Walt must have thought we were okay. The rule of thumb around the Studio was that if you didn’t hear from Walt, you were doing okay. Carl got along fine with Walt by keeping to himself. He was always a loner, but not in an unfriendly sense. He handled his won business and kept quiet about it.

It was rare than anyone could be at the Studio for several years without a few gruff words from Walt. I can’t recall Carl ever being criticized, so Walt must have had a high regard for him. He was well though of by his peers too, because our unit had to turn in a picture to Jack King every six weeks and never missed.

Korkis: What did Disney think of your own story work?

Hannah: Walt was a great one for having a little fun at your expense in front of other people, but then he’d turn around and do something nice for you in private. One day while I was working as a storyman, I got my check, and it was much more than I had been paid before. So I checked to see if they were aware of the mistake and was told that it wasn’t a mistake. Walt had felt there was too great a discrepancy between what other storymen were making and what I was paid, so he gave me a raise. It was his way of saying that he felt I was pulling my weight in the story department.

From “Pirate Gold”

Korkis: About this time, you and Barks were assigned to work on “Pirate Gold”. How did that project start?

Hannah: A fellow at the Studio named John Rose took us to meet Elanor Packer of Western Publishing. We were doing all the Donald Duck stories and story sketches at the time, so they probably felt we could work out that story, too.

We were given a typewritten script broken down by panels. For each panel, the script had a brief scene description and, of course, the dialogue that needed to appear in that panel. How we divided up the pages was left up to us.

Korkis: How did you go about working on the book?

Hannah: After dividing up the pages, we worked on weekends or evenings. I penciled about a page and a half to two pages a weekend. We would draw it up in blue pencil and then Western would have to see it before we went ahead with the inking. The inking went faster than the penciling, and I can’t recall that we made any major changes to our blue-pencil work.

Carl and I had several meetings on the weekends so that the props and settings we drew would look the same. There had to be the same pots on the stove, for instance. We didn’t have any difficulty synchronizing styles. We both fell into it and were surprised how closely the styles matched, especially since we were working in two different houses. Looking back at the art now, it’s sometimes difficult for me to tell which pages are my work and which are Carl’s.

Carl and I had several meetings on the weekends so that the props and settings we drew would look the same. There had to be the same pots on the stove, for instance. We didn’t have any difficulty synchronizing styles. We both fell into it and were surprised how closely the styles matched, especially since we were working in two different houses. Looking back at the art now, it’s sometimes difficult for me to tell which pages are my work and which are Carl’s.

Korkis: Did you use special reference materials?

Hannah: Carl did most of the ship exteriors, so no doubt he looked up some background material.

Korkis: Was it a pleasant experience working on the book?

Hannah: I remember having a lot of fun with it. It was a new experience drawing comic strips, and I was able to pick up a little extra money doing it. Western gave us a few dozen copies of that issue. [Barks comments: “I must have been gone from the Studio when that happened. The only copies of ‘Pirate GoldJack Hannah’ I got were two I bought in a grocery store.”] When I think of how I let my kids tear through those comics! But in those days, they only cost a dime, and nobody knew that they were going to be worth something.

Korkis: We’ve identified you work in at least three other Duck stories for Western. [“Donald Duck in School Days” [Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories #37], “Sleepy Time Donald” [Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories #78], and “Santa Claus’ Visit” [a 1943 giveaway].] What do you remember about drawing them?

Hannah: Very little, I’m afraid. Until you showed me the stories, I would have said that the only comic book art I drew was for “Pirate Gold”. Yet those stories are definitely my work. I can tell by the way the Duck is drawn. Little things like the position of a hand or a foot are dead giveaways.

PART TWO of this interview – CLICK HERE!

THAD KOMOROWSKI is a writer, journalist, film restorationist and author of the acclaimed (and recently revised) Sick Little Monkeys: The Unauthorized Ren & Stimpy Story. He blogs at

THAD KOMOROWSKI is a writer, journalist, film restorationist and author of the acclaimed (and recently revised) Sick Little Monkeys: The Unauthorized Ren & Stimpy Story. He blogs at

Jim Korkis also incorporated this material into the book “From Donald Duck’s Daddy To Disney Legend” (2016) .

The book is billed as if the author is Jack Hannah –

with a sideline box which says “With additional Historical Content by Jim Korkis”

There is a a foreword by Bill Justice.

In one of his Animation Anecdotes columns posted here on Cartoon Research, Jim Korkis wrote that he was in his late teens when he first met Jack Hannah, which would have been in the early 1970s. An interview for his school paper that was meant to take an hour wound up lasting for three, and at the end of it Hannah phoned a couple of his colleagues who lived nearby in Glendale and urged them to talk to Jim about their careers. By the time these interviews took place in 1977-83, Jim had established a warm rapport with Hannah, setting the pattern for the hundreds of interviews he would later conduct with key figures in animation history.

Any mention of Hannah’s home town reminds me that Nogales, Arizona is also the birthplace of Christine McIntyre, co-star of many Three Stooges shorts. I have no idea whether they ever knew each other, but they were born less than two years apart, and Nogales isn’t that big of a town.

This interview reminds me how much I miss Jim’s weekly articles. I look forward to reading Part 2 tomorrow!