My “Top Ten” anime choices have become a “Top 15” (ten, plus five runner-ups). Here are two more I have to add to the list:

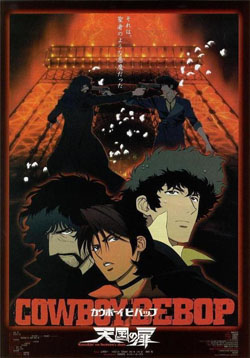

14. Cowboy Bebop: Knockin’ At Heaven’s Door. Cowboy Bebop: Tengoku no Tobira. Produced by Sunrise, Inc. and Bones, Inc. Directed by Shinichiro Watanabe. 116 minutes. September 1, 2001.

The 26-episode Cowboy Bebop TV series was fantastically popular in both Japan and the U.S. Both publics demanded a theatrical feature. Due to the nature of the TV series, the feature was developed as a stand-alone story occurring between episodes 23 and 24 rather than as a sequel. The U.S. title, release date April 4, 2003, was more simply Cowboy Bebop: The Movie. Unlike most anime movie spinoffs of popular TV series that assume that the audience is already very familiar with all the main cast, Cowboy Bebop: Knockin’ At Heaven’s Door stands nicely as a totally independent work.

The 26-episode Cowboy Bebop TV series was fantastically popular in both Japan and the U.S. Both publics demanded a theatrical feature. Due to the nature of the TV series, the feature was developed as a stand-alone story occurring between episodes 23 and 24 rather than as a sequel. The U.S. title, release date April 4, 2003, was more simply Cowboy Bebop: The Movie. Unlike most anime movie spinoffs of popular TV series that assume that the audience is already very familiar with all the main cast, Cowboy Bebop: Knockin’ At Heaven’s Door stands nicely as a totally independent work.

The movie is set in 2071 in Alba City, the capital of Mars; a thinly-disguised New York City. The movie’s Japanese September 1, 2001 release date eerily prefigured the September 11 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center by less than two weeks. The “cowboy” bounty-hunter crew of their Bebop spaceship is relaxing a few days before Halloween in Alba City, the largest city in the Solar System, when a terrorist attack there releases a deadly pathogen that kills over 500 people. The Martian government offers a 300 million woolong reward, the largest bounty in history, for the capture of the terrorist(s). The Bebop five – martial-arts expert Spike Spiegel, ex-interplanetary policeman Jet Black, femme fatale Faye Valentine, Crazy Ed the juvenile (female) computer wunderkind, and Ein the “data dog” Corgi – naturally go after it. Complications immediately ensue, notably the likelihood that Vincent Volaju, the terrorist, is actually a renegade Martian government agent out for revenge (against what?), and that the Martian government has sent out its own secret hit squad, led by the beautiful but ultra-deadly Elektra, to kill both Volaju and anyone who gets close to learning his secret: the Bebop team.

The mystery-thriller is excellently developed, with two superbly-choreographed showpiece martial-arts battles between Spike and Volaju; one aboard a suspension tram high over the city, and the other on the girders of a building under construction while a Halloween parade passes below. The only serious flaws are that futuristic Alba City and its “Moroccan ethnic neighborhood” are too obviously based on the current cosmopolitan NYC; and the Japanese filmmakers still don’t understand the difference between American traditional Halloween trick-or-treating and the gaudy annual Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

15. The Animatrix. Produced by Village Roadshow Pictures. Directed by Michael Arias, Spencer Lamm, Andy Wachowski, Larry Wachoski. 101 minutes. June 3, 2003.

This is admittedly only debatably an anime production. American directors Andy and Larry (later Lana) Wachowski were big fans of Japanese animation and Chinese martial-arts movies. They based their 1999 live-action, VFX-heavy s-f mega-hit The Matrix upon them. They took advantage of going to Tokyo on a 1997 promotional tour for The Matrix to visit some of their favorite anime directors. Then, after The Matrix was released, they commissioned nine approximately ten-minute animated films set in the same world, for release together as The Animatrix. Four of the nine were written by the Wachowskis, and one was written and directed by American animator Peter Chung, animated at Studio Madhouse; and all nine plus the resulting feature had plenty of American input. As a result, many critics argue that it is really an American imitation-anime feature. I say that if it looks like an anime feature, and each segment has a crucially-anime production origin, The Animatrix is an anime feature.

The Animatrix was released direct-to-DVD in America, but theatrically in some countries; and in Japan on May 24, over a week ahead of the U.S. release. I first saw it in May 2003 in a movie setting, in a Warner Bros. studio large-screen screening room, along with about a dozen of the animation press when WB was just about to release the American DVD, while I was working post-Streamline briefly for Animation World Network. As part of the same publicity tour, we were taken into a large meeting room for a video hookup to a similar room in Tokyo where most of the Japanese directors were gathered, for a live Q&A. I remember that Shinichiro Watanabe said that he had developed some scene by asking himself how kung-fu actor Bruce Lee would have handled it, and Koji Morimoto (I think) burst in, “You always ask yourself what Bruce Lee would have done in every situation!”

The Animatrix was released direct-to-DVD in America, but theatrically in some countries; and in Japan on May 24, over a week ahead of the U.S. release. I first saw it in May 2003 in a movie setting, in a Warner Bros. studio large-screen screening room, along with about a dozen of the animation press when WB was just about to release the American DVD, while I was working post-Streamline briefly for Animation World Network. As part of the same publicity tour, we were taken into a large meeting room for a video hookup to a similar room in Tokyo where most of the Japanese directors were gathered, for a live Q&A. I remember that Shinichiro Watanabe said that he had developed some scene by asking himself how kung-fu actor Bruce Lee would have handled it, and Koji Morimoto (I think) burst in, “You always ask yourself what Bruce Lee would have done in every situation!”

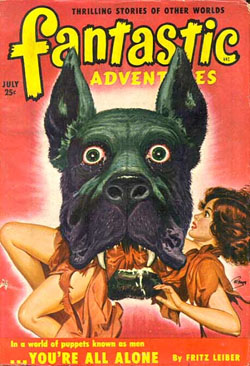

The plot of “reality” being a simulation controlled from outside, and of the main characters learning the truth and trying to escape it, goes back to the 1940s in literary science fiction/fantasy. Robert A. Heinlein and Fritz Leiber wrote fantasy novels in which the omnipotent puppet-masters were gods or demons. The earliest s-f, in which a man is unknowingly living inside a computer’s fantasy world, and a psychiatrist-protagonist has to persuade him to come out, was the short story “Dreams Are Sacred” by Peter Phillips (1948). But, not counting the three 1980s Megazone 23 anime features that were virtually unknown to the American general public, the concept had never been used cinematically until the Wachowskis introduced it in The Matrix. (Unless you count Paramount’s June 1998 feature The Truman Show, featuring Jim Carrey as the unknowing actor Truman Burbank; but in that he was the only character for whom reality was false.) It was a blockbuster hit, and its followup The Animatrix was, to me, just as good: nine tightly-written and excellently-directed anime variations on the theme. For the rest of this column, I am simply going to reprint my review from Emru Townsend’s fps, June 10, 2003:

“Ever since the live-action (but CGI-intensive) sci-fi feature The Matrix appeared in 1999, writer-directors Larry and Andy Wachowski have acknowledged their inspirational debt to Japanese animation such as Akira and Ghost in the Shell. Now they have demonstrated their inspiration even more clearly with this delightful win-win-win project. The Animatrix has enabled them to work with some of their favorite anime directors; it has resulted in an excellent new work of anime; and it will undoubtedly give anime a boost among the general American public.

The Matrix is such a cinematic landmark that it is hard to imagine anyone not having the background to enjoy The Animatrix. The plot of someone learning that the whole world is a delusion created by mega-powerful beings to lull him (and usually all humanity) goes back to the 1940s with such surrealistic sci-fi thrillers as Robert Heinlein’s The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag and Fritz Leiber’s You’re All Alone. Movies on this theme have been rarer, but the Wachowskis may have been aware of the 1980s anime Megazone 23. In any case, the public should be familiar enough with the basic concept of The Matrix that The Animatrix will stand on its own, even if some specific references such as blue pills and red pills may be missed.

The Matrix is such a cinematic landmark that it is hard to imagine anyone not having the background to enjoy The Animatrix. The plot of someone learning that the whole world is a delusion created by mega-powerful beings to lull him (and usually all humanity) goes back to the 1940s with such surrealistic sci-fi thrillers as Robert Heinlein’s The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag and Fritz Leiber’s You’re All Alone. Movies on this theme have been rarer, but the Wachowskis may have been aware of the 1980s anime Megazone 23. In any case, the public should be familiar enough with the basic concept of The Matrix that The Animatrix will stand on its own, even if some specific references such as blue pills and red pills may be missed.

The “making of” documentaries among the DVD’s special extras describe how the Wachowskis used a 1997 trip to set up the Japanese theatrical release of The Matrix to meet some of their favorite anime creators. Then, after the movie’s release in Japan, they asked those creators to participate in an animated version which would showcase their distinct styles.

Their point man was Michael Arias, an American CGI animation consultant who had been working with Japan’s animation studios for several years; including both the Madhouse studio and Studio 4°C, which became their two principal production studios. Arias sent out the Wachowski Brothers’ invitations, and served as the communication channel between the individual directors and the Wachowskis, who were in Sydney filming the two Matrix sequels, The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions.

The notes say that the Wachowskis wrote four of the nine stories in The Animatrix and approved five stories by the anime creators. The Final Flight of the Osiris, which opens The Animatrix (and was the segment shown by Warner Bros. as a theatrical short starting two months before the release of The Matrix Reloaded), was apparently the story that the Wachowskis concerned themselves with the most, since it sets up the plot for Reloaded: the human rebels’ scoutship Osiris sacrifices itself to warn the last human city, Zion, that the Machines have discovered it and are planning to overwhelm it. This was CG-animated by Square USA, the Honolulu studio created to produce the all-CGI feature Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within. In general Osiris looks even better than Final Fantasy; possibly because the animators were more experienced in using their CG techniques by the time they got to The Animatrix. Director Andy Jones describes how he took the Wachowskis’ story and expanded or tweaked some of its aspects to increase its dramatic impact.

The Second Renaissance Parts I and II are also a Wachowski story, both directed by Mahiro Maeda. Maeda is best known for smoothly blending CGI with traditional 2D animation for OAV and TV anime serials such as Blue Submarine No. 6, usually at Studio Gonzo. This two-part story takes the form of an educational film documenting the evolution of the Machines from menial labor for humans, to self-aware protestors demanding equality with humans, to an “ethnic group” persecuted by arrogant humans that is finally forced to subjugate humanity in its own defense. Maeda had to summarize two centuries of dramatic future history in two films of about ten minutes each. The art design encompasses everything from shimmering Hindu mandalas to the gritty overcrowded future metropolises of French artist Moebius (Jean Giraud). Some of the glimpses are not too convincing (technological labor efficiency is not really increased just by churning out vast quantities of robotic duplicates of non-tech human slaves), but it sure does look impressive!

The Second Renaissance Parts I and II are also a Wachowski story, both directed by Mahiro Maeda. Maeda is best known for smoothly blending CGI with traditional 2D animation for OAV and TV anime serials such as Blue Submarine No. 6, usually at Studio Gonzo. This two-part story takes the form of an educational film documenting the evolution of the Machines from menial labor for humans, to self-aware protestors demanding equality with humans, to an “ethnic group” persecuted by arrogant humans that is finally forced to subjugate humanity in its own defense. Maeda had to summarize two centuries of dramatic future history in two films of about ten minutes each. The art design encompasses everything from shimmering Hindu mandalas to the gritty overcrowded future metropolises of French artist Moebius (Jean Giraud). Some of the glimpses are not too convincing (technological labor efficiency is not really increased just by churning out vast quantities of robotic duplicates of non-tech human slaves), but it sure does look impressive!

Kid’s Story, again written by Andy and Larry Wachowski, also ties into Reloaded by “introducing” a new character in the live-action feature. The plot is basically a reprise of the original Matrix story, with a high-school computer hacker playing Neo’s role and Neo matured into the Morpheus role of his mysterious mentor. Director Shinichiro Watanabe (Cowboy Bebop) deliberately chose a “rough line” art style closer to that of many independent short films than the usual polished style of “professional” animation.

Program, by Yoshiaki Kawajiri, is one of the director-created stories accepted by the Wachowskis. If they started out wanting to make a movie with their favorite anime directors, Kawajiri of Wicked City, Ninja Scroll, and Vampire Hunter D: Bloodlust must have been one of their first choices and they probably wanted to give him as much creative freedom as possible. The dialogue of Program fits right into the Matrix world, but the visual sequence would fit right in with the samurai-ninja fantasy Japan of Ninja Scroll—although looking ten times better because of the much higher animation budget.

World Record is also written by Kawajiri, but he did not have time to direct both short films so he got an okay to let Takeshi Koike, his young protégé at Madhouse, do it. It is totally different in theme, looking much more modern and “American”—in fact, Koike’s art looks so much like an exaggeration of Peter Chung’s style (Chung has worked at Madhouse) that the viewer may mistake World Record for Chung’s chunk of The Animatrix. A black athlete trying to set a new record races out of the false Machine-created world despite the efforts of several Agents to keep him deluded.

World Record is also written by Kawajiri, but he did not have time to direct both short films so he got an okay to let Takeshi Koike, his young protégé at Madhouse, do it. It is totally different in theme, looking much more modern and “American”—in fact, Koike’s art looks so much like an exaggeration of Peter Chung’s style (Chung has worked at Madhouse) that the viewer may mistake World Record for Chung’s chunk of The Animatrix. A black athlete trying to set a new record races out of the false Machine-created world despite the efforts of several Agents to keep him deluded.

Beyond is by Koji Morimoto, best known to American anime fans for the Franken’s Gears sequence in the 1987 film Robot Carnival (which might be considered the predecessor of The Animatrix since it was the first anthology feature consisting of nine short films by different directors on the theme of intelligent machines and humans). This is the lightest tale in the movie, about a group of children who have found a glitch in the “reality” created by the Machines, and who use it for fantastic fun and games until a work force of Agents chase them off and repair it.

A Detective Story was written as well as directed by Shinichiro Watanabe. It looks totally different from Kid’s Story and is his tribute to the black & white film noir detective movies of the 1940s and ’50s. Watanabe says the Wachowskis liked his idea of a noir-type downbeat story about a private eye who tries to escape the Matrix but fails.

Matriculated, by Peter Chung, ends The Animatrix on what is both a depressing and encouraging theme. A group of human rebels try to separate one of the Machine’s killer units from its group mind, give it free will, and persuade it to join the humans as an equal. Chung’s visuals of the mind-alteration of the machine are reminiscent of the early CG psychedelia of such 1980s shorts as Scuilli’s Quest: A Long Ray’s Journey into Light, but with the benefit of twenty years’ worth of technical improvements and a more dramatic plot. This particular effort fails, as it must since The Animatrix is set prior to the continued dominance of the Machines in Reloaded and Revolutions. It is too soon for a happy ending, but it does hint at how a happy ending might be possible. The Animatrix is impressively successful, both as a single feature encompassing many different styles of animation, and as a sci-fi feature.”

Matriculated, by Peter Chung, ends The Animatrix on what is both a depressing and encouraging theme. A group of human rebels try to separate one of the Machine’s killer units from its group mind, give it free will, and persuade it to join the humans as an equal. Chung’s visuals of the mind-alteration of the machine are reminiscent of the early CG psychedelia of such 1980s shorts as Scuilli’s Quest: A Long Ray’s Journey into Light, but with the benefit of twenty years’ worth of technical improvements and a more dramatic plot. This particular effort fails, as it must since The Animatrix is set prior to the continued dominance of the Machines in Reloaded and Revolutions. It is too soon for a happy ending, but it does hint at how a happy ending might be possible. The Animatrix is impressively successful, both as a single feature encompassing many different styles of animation, and as a sci-fi feature.”

Fred Patten (1940-2018) was an internationally respected comics and animation historian. He has written about anime or comic books for publications ranging from Animation Magazine and Alter Ego to Starlog. He was a contributor to The Animated Movie Guide (2005), and is author of Watching Anime, Reading Manga (2004, Stone Bridge Press), a collection of his best essays, and Funny Animals and More (2014, Theme Park Press), based upon his early columns here on Cartoon Research. He passed away on November 12th, 2018.

Fred Patten (1940-2018) was an internationally respected comics and animation historian. He has written about anime or comic books for publications ranging from Animation Magazine and Alter Ego to Starlog. He was a contributor to The Animated Movie Guide (2005), and is author of Watching Anime, Reading Manga (2004, Stone Bridge Press), a collection of his best essays, and Funny Animals and More (2014, Theme Park Press), based upon his early columns here on Cartoon Research. He passed away on November 12th, 2018.

I have been corrected that Japanese filmmakers DO understand the difference between trick-or-treating and the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. They have deliberately combined the two for a dramatic climax to their movies and TV series, since children’s individual trick-or-treating isn’t that dramatic.

Wouldn’t surprise me they felt they needed to get something bigger out of it (of course when I think of a parade on Halloween, it’s the one my grade school did where we all had to walk around the entire campus in our costumes).

I just got this personal e-mail from “steveatserve”, which I am copying to here since it is of general interest.

“I think we might like to know more of your list. I’m rewatching top 10. I owned all but the first. Where would you put the other Ghibli movies, Paprika, Grave of Fireflies, Patlabor 1 & 2, Neotokyo, Memories, Tokyo Godfathers, Millenium Actress, Up on Poppy Hill. I would like to see your top 50 or top 100 list, I think.”

My “other” top fifty list should go up next. It’s alphabetical, though; I don’t try to figure out which I like better than others. It also covers only the standalone movies like the Ghibli features, Satoshi Kon’s, and “Night on the Galactic Railroad”; not the movies based on series like “Patlabor XIII”, the “Attack on Titan” movie, any movies based on Rumiko Takahashi’s TV series or “Slayers” or “Full Metal Alchemist”, etc.