In 1927, Charles Lindbergh won the Orteig Prize for his nonstop transatlantic flight from New York to Paris. The accomplishment catapulted Lindbergh into worldwide fame and marked a significant milestone in the development of aviation. Capitalizing on the excitement Lindbergh’s flight brought to aviation, three prominent businessmen in Cincinnati, Ohio, founded the Aeronautical Corporation of America in November 1928. The company would be known by the acronym “Aeronca,” which became synonymous with light planes in America.(1)

Aeronca became the first company to build a viable and successful general aviation Plane in the United States. The Aeronca C-2, also known as the “Flying Bathtub,” was the first monoplane manufactured by the company at its plant at Lunken Airport in Cincinnati.(2) The company prospered even during the Great Depression and steadily increased production of its single-engine two-seater light aircraft. The planes were known for quality, safety, low cost and were easy-to-fly, which made aviation accessible to a much wider audience.

The plane’s construction was a combination of steel and wood with the fuselage made out of welded steel tubing. The aft section of the fuselage formed “a triangular cross-section with diagonal bracing,” which became standard for all future Aeronca designed planes. The wings and tail surfaces were built out of wood spars and ribs. The use of wood in airplane construction was typical of the early days in aviation development.(3)

By 1938, Aeronca introduced the Model 50 Chief listed as a “single-engine two-seat high wing cabin monoplane.” The Model 50 Chief evolved over several years until 1941 when the Model 65 Super Chief was introduced, which also spawned the Military version known as the Aeronca L-3, which was dubbed the “Grasshopper.” It received that nickname because of its ability to take off and land in “off-airport” conditions— meaning the plane could quickly arrive or depart from a field or any reasonably flat surface area.

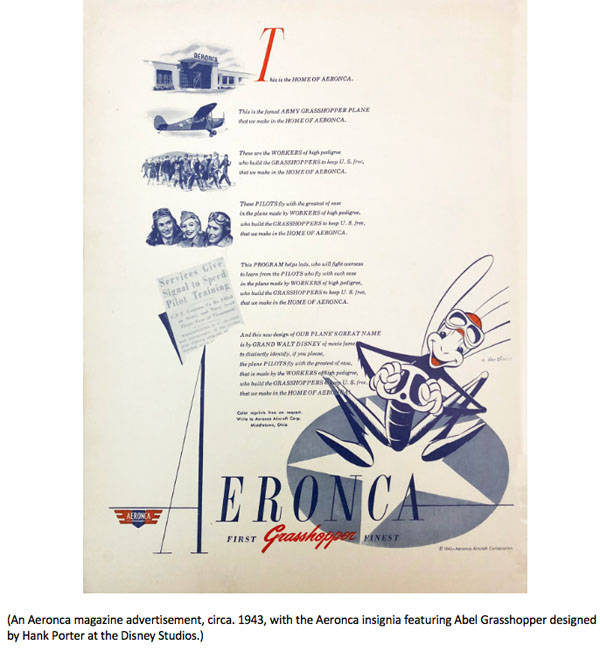

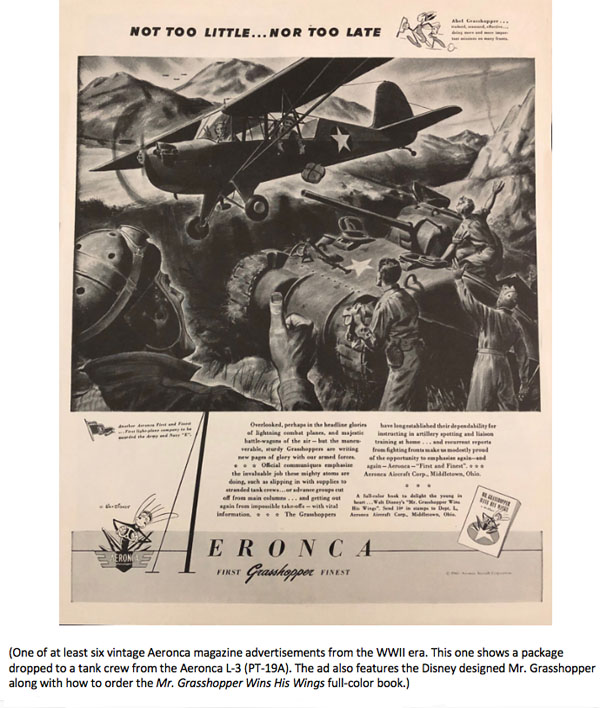

There are several minor variants of the Aeronca L-3 Grasshopper. Still, all were lightweight aircraft that were used primarily for artillery observation, reconnaissance, coastal, civil air patrol, and to deliver small packages to soldiers stranded or in need of some assistance in rugged areas.(4) One magazine ad for the Grasshopper shows a pilot tossing out a packet of “supplies to a stranded tank crews.”(5) Additionally, the plane was used as a trainer for new pilots entering the Army Air Forces during WWII.

Aeronca produced more than 2100 Grasshopper planes for the military, which was certainly enough to warrant the creation of training films for these aircraft. In early 1943, Aeronca and The Walt Disney Studios through the First Motion Picture Unit Army Air Forces (FMPUAAF) created five training films in total covering the following topics: Preflight and Daily Inspections; Landing Gear, Wheels & Brakes; Propeller and Power Plant; Flight Controls and Control Surfaces, and Engine Change. This program of films was approved by Colonel Waters, Director of Individual Training Army Air Forces, on December 7, 1942. Most of the Aeronca training films, which involved repairs and maintenance of the Grasshopper, were shot on a sound stage at the Walt Disney Studios Burbank lot with some exterior and flying shots filmed at the Metropolitan Airport, now known as Van Nuys Airport, which is approximately twelve miles from the Disney Studio lot in Burbank.

The contract was signed on February 2nd, 1943, for Walt Disney Productions to create the Aeronca training films “not to exceed $125,000.00.” An Aeronca L-3 Grasshopper aircraft was dispatched to Burbank, arriving at the Lockheed Air Terminal on February 26th, 1943. The plane was then officially consigned to the FMPUAAF but had not yet arrived at the Disney Studios lot. On March 3rd, Robert Spencer Carr of the Training Films Division at Walt Disney Productions sent a letter to Carl Friedlander, then president of Aeronca. Carr wrote that filming had been delayed because “the FMPUAAF knows all about your film project and are cooperating in spirit, but unfortunately they have not yet received authorization from their superiors to let our Studio use the plane in any way. Consequently, we have been unable to start shooting.”(6)

The letter went on to detail that a large shipment of tools had arrived at the Studio along with additional tools procured from a local flight school for the film shoot. The Studio was making every effort “to break the deadlock” to get the plane delivered to the Studio for filming. Carr concludes, “Please thank Charley Smith for his help in getting the plane to us. It is too bad that after flying across the continent, they can’t make the last two miles from the airport to our Studio.”(7)

Eventually, two aircraft in total were loaned to Disney on March 6, 1943, for filming; a PT-23AE, serial No. 2-47496, and a PT-19A serial No. 42-34269. The PT-19A plane, with its wings removed, was placed on a flatbed truck at the Lockheed Air Terminal and trucked the last few miles to the Disney Studio lot where it could be reassembled on a sound stage for filming. The U.S. Army Air Forces designation “PT” stood for primary trainer and was used for pilot training as well as forward reconnaissance and other missions. The PT-19A was equipped with a 200 hp L-440-3 engine and wooded propeller, made by Fairchild. The PT-23AE had a 220 hp Continental R-670 engine with a wooden propeller and equipped with flight instrumentation. Both planes accommodated a pilot and student pilot or passenger in tandum.(8)

Once the planes were reassembled at the Studio, Privates Francis Panetta and Louis Gianotti were assigned to the Disney Studios, “through the efforts of the First Motion Picture Group,” to work on the Aeronca Project. Both men being aircraft mechanics, were assigned the task of doing the necessary work on the aircraft for the training films. This work included maintenance and repairs on the landing gear, wheels & brakes; propeller and power plant; flight controls and control surfaces, and engine change-out. Production Manager Dick Pfahler requested that these two men be given the authorization to sign for “payment of meals partaken in your restaurant [commissary]” while they were working on the lot.(9) The mechanics slept in Barracks-D at the Hal Roach Studios, also known as “Fort Roach,” in Culver City.

The photography of these training films was very straight forward with the entire Aeronca project shot on 35MM, black and white film, including the live-action, slide film, and “cartoon intercut.” There was a specific note in the memo stating “there will be no color in the Aeronca Project series of pictures,” no doubt due to costs.(10) The still photography, which was used for the slide film portion of the project, was scheduled for Monday, April 12th, 1943, followed by interior filming on Wednesday, April 14, and the engine change-out filming done on Friday, April 16. With filming on the sound stage completed at the Studio, technical advisor Hugh B. Du Valle from the Headquarters, Air Services Command Technical Data Section, Maintenance Division, sent a letter to Ben Sharpsteen, project producer, to verify the completeness of the filming. “I wish to state that I have been present at all times while these motion pictures were being made,” Du Valle wrote, “I further state that you and the director at the Air Forces mechanics who performed in films and all Walt Disney personnel connected with the making of these films have cooperated with me fully, complied with my requests and given me every opportunity to fulfill my duties as technical advisor.” It reads like a classic cover-your-butt “insurance policy” for Disney if the Army Air Forces claimed something wasn’t covered in the films. Du Valle continued, “I further state, that I have viewed and inspected all the exposed film, (exclusive of titles and animation) and can certify that all servicing and maintenance operations and all other methods and procedures demonstrated therein, together with all tools and techniques used and all other scenes occurring in the films, are correct and in accordance with accepted Air Services Command maintenance practices, to the best of my knowledge and belief. Although I have not yet read the complete narration, so far as the motion pictures themselves are concerned, I hereby approve them.”(11) This letter was the final approval of the content filmed for the maintenance film portion of the Aeronca Project. There was still additional footage to be shot for the exteriors.

The call sheet for filming the exterior and flying shots was on Tuesday, April 27th, at the Metropolitan Airport. That gave them more than a week to get the plane disassembled, trucked back to the Lockheed hanger, then reassembled and ready for flying shots that needed to be filmed. The Army Air Forces supplied technical assistance to the film crew with several military personnel, including Hugh Du Valle, pilot Lt. Iben Browning, Sgt. John Shea, and Sgt. Don Williams. It was Lt. Browning who flew the PT-19A, which had been brought back to the Lockheed Terminal, with a Sgt. Panetta as a passenger, from the Lockheed to the Metropolitan Airport. Then Browning was driven back to Lockheed to fly the PT-23 to Van Nuys with a Sgt. Denison as the passenger. Once both planes were at the Metropolitan Airport, the exterior filming proceeded with Sharpsteen as a producer, directors Gene Anderson and Graham Heid, assistant director Harvey Dwight, production manager Barton Adams and a crew of nine others. The exterior photography was wrapped up in one day.(12)

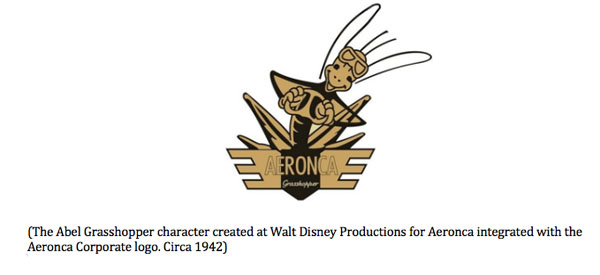

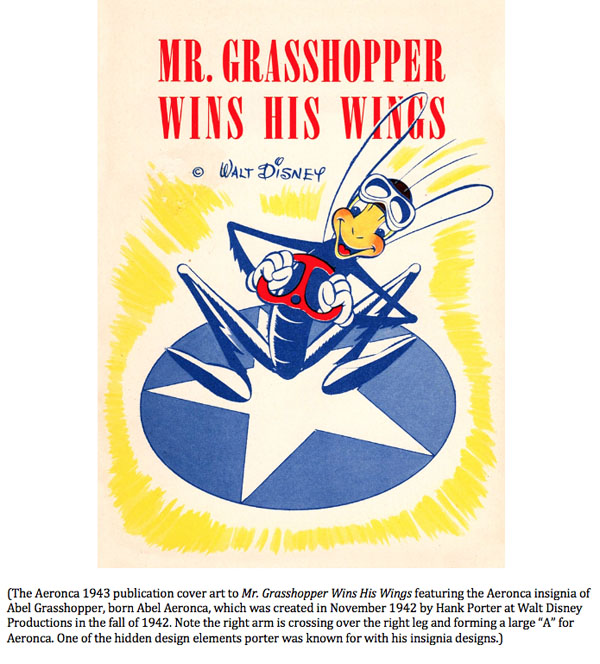

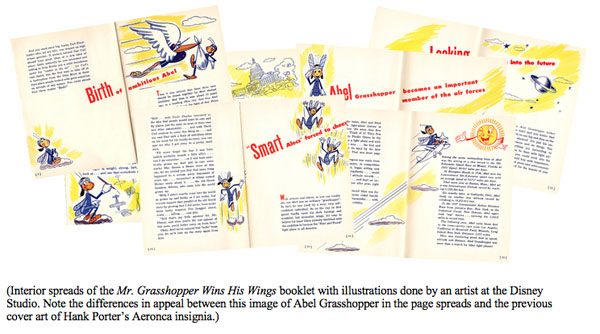

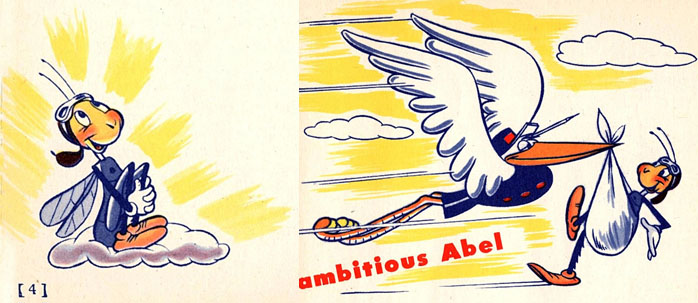

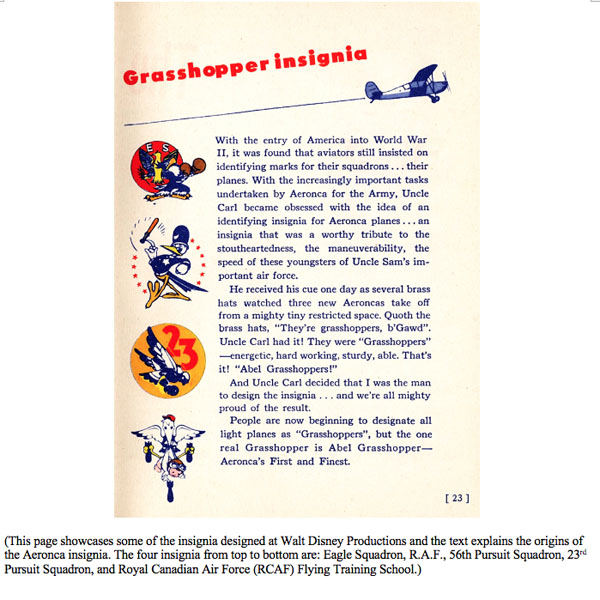

Once the Aeronca film production was wrapped, the Studio did one other small job for Aeronca—a 24-page pamphlet titled Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings that was based on the insignia Disney artist Hank Porter designed for Aeronca in November 1942.(13) Hank Porter was head of the unit that created the insignia designs at Walt Disney Productions. Although Porter did the initial design of Abel Grasshopper for the Aeronca insignia, it is very doubtful that he did the drawings for the pamphlet because of the distinct difference in the drawing styles. The Porter insignia character has much more appeal and subtle design flair than the drawings executed in the pages of the booklet. The body shape, variations of how the legs are interpreted, the wings, shoes, and the facial features of Abel Grasshopper are all different in the pamphlet interior page illustrations of the character. In contrast, Porter’s insignia version, on the cover, is much more pleasing to view with the use of thick and thin lines and a more refined design esthetic overall.(14)

Close up of art on pages 4 and 5

The Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings booklet is written in the “voice” of Walt Disney and Abel Grasshopper. Beginning with Walt telling the story of how Aeronca started in Middleton, Ohio, with “3 wise men… and an idea.” One of the business partners was “C.P. Taft, the half-brother of one of our great United States Presidents who visualized the many wonderful things a really light airplane…could do for this wonderful country of ours.” The other two founders of Aeronca are aircraft engineer Jean A. Roche, who designed the Aeronca C-2 monoplane, and Carl Friedlander “who, we are told, was weaned on high octane gasoline.” Walt continues his story of the origins of Aeronca and by page 5, turns it over to “Abel Grasshopper, who was first known as Abel Aeronca, “let’s hear a few words from our hero himself. So…Take it away, Abel.” To which, Abel responds, “O.K. Mr. Disney…and …to my good readers, Contact!”(15)

Abel tells his story in his own words, repeating some of the material we already learned from Walt. And he is not beneath name dropping speaking about “that grand guy Eddie Rickenbacker,” the World War 1 fighter ace and Medal of Honor recipient. After that, Abel gets down to business and explains the Aeronca family tree starting with designer Roche who “drew hundreds of plans…hundreds of them…but looking back over these, it’s pretty easy to see that his real dream was about one plane, in particular, a plane light in weight, strong, fast, good to look at…and one that everybody could fly!”(16) This last statement is the genius of the Aeronca planes—anyone could fly them.

After giving background on the formation of Aeronca, Abel then turns it back over to Walt, saying, “And that’s my little amateur bit, Mr. Disney, and since you’re the real spinner of this yarn, you’d better carry on from here.”(17) At which point, the narrative voice switches back to Walt, who responds, “Okay, Able we’ve enjoyed this “hello” from you. So we’ll take up the story again from here.” Walt goes on to discuss the attributes of the Aeronca plane’s “sleek fuselage and youthful, but muscular, wings, it’s easy to believe his inner fibres [sic] actually throbbed with ambition to become the “First and Finest” light plane in all America.”(18) Evoking a Horatio Alger analogy, Walt tells the reader that, “Abel proved to be an “ace” performer from the day he was born. So finely was he balanced…so perfectly was he controlled…you could literally call him a glider with a motor! And in spite of all his lightness, his strength and stamina surprised everyone.” Not to forget the fact that the country was at war, Walt uses a derogatory term describing the enemy at that time as he continues, “Becoming a champion, he had many imitators, of course. But even the Japs today have discovered that imitation is only the “highest form of flattery.” Abel went out of his way looking for competition…they couldn’t match him for speed, agility and surefootedness on the ground nor in the air.”

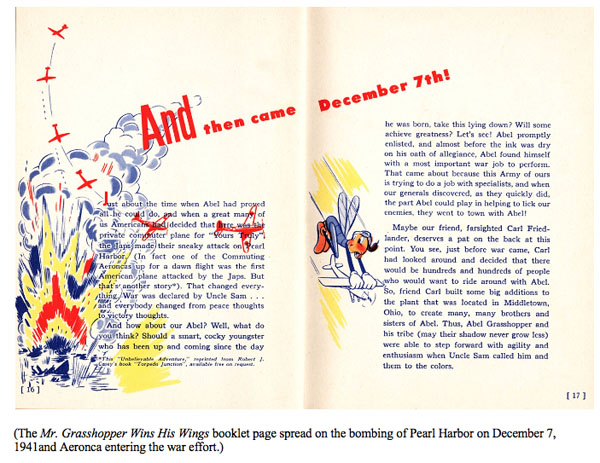

With all of the great attributes described, it all boiled down to convincing the public to “do any sky-riding in featherweight flyin’ machines.”(19) Aeronca hired, in the early days of the company, an experienced pilot named Johnny Jones to fly their light plane coast to coast “from the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic Ocean,” which garnered front-page news coverage for the aircraft. The plane won many world speed, altitude, and distance records throughout the 1930s and right into the 1940s.(20) Aeronca proved to be a tremendous private commuter plane. “In fact, one commuting Aeroncas [sic] up for a dawn flight was the first American plane attacked” by the Japanese during their sneak attack on Peral Harbor in Hawaii on December 7, 1941. Since then Aeronca had proved itself as a reliable, sturdy aircraft, the U.S. Army Air Forces enthusiastically called upon Abel Grasshopper to become “an important member of the air forces.”(21)

The Aeronca Grasshopper aided the U.S. Armed Forces around the world “with courier work, artillery observation, aerial photography, coastal patrol, civil air patrol, and acting as air-born troop carriers.” It was even the “first light ambulance plane” used during wartime. When the “Army Air Corps sent out a recent emergency call for glider builders,” Aeronca was all ready to go with a Grasshopper model with no engine— accomplished in just nine days after the blueprint arrived.(22)

The booklet begins to wrap up with our hero Abel Grasshopper looking towards the future with optimism. “Perhaps if you could peek into his mind,” Walt says, “you, too, would hop with impatience. For all the ideas and planes and achievements to come are intended for the benefit of you and yours.”(23) Walt’s text at the end of the booklet also gives much praise to Carl Friedlander, the president of Aeronca Aircraft Corp. at that time, saying, “because his life is so closely wrapped up with the production of planes worthy of the description, “First and Finest,” that it is impossible to talk of the one without mentioning the other.” After all, Friedlander personally was involved with the training films, and Walt ends his praise for him with, “America largely has him to thank for most of the innovations in this field of aviation.”(24)

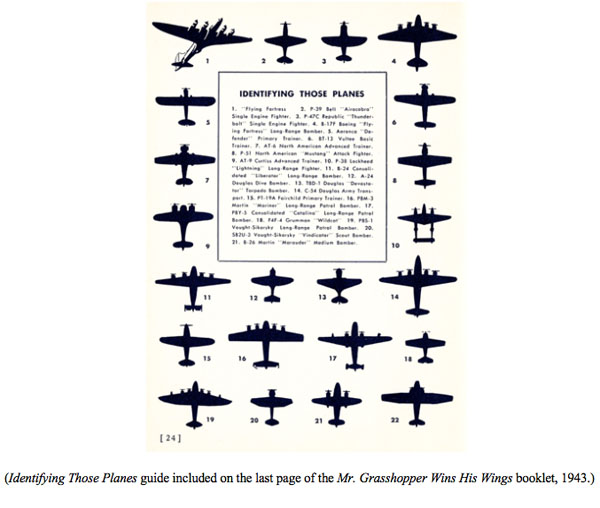

The penultimate page in the pamphlet is devoted to military insignia. It’s on this page that we learn the roots of the Aeronca Grasshopper insignia. “With the entry of America into World War II, it was found that aviators still insisted on identifying marks for their squadrons…their planes. Carl became obsessed with the idea of an identifying insignia for Aeronca planes…He received his cue one day as several brass hats (Military Generals) watched three new Aeroncas take off from a mighty tiny restricted space.” One of the Generals quipped, “They’re grasshoppers, b’Gawd,”(25) and to Carl, it was an epiphany, “they were “Grasshoppers”—energetic, hard-working [sic], sturdy, able. That’s it! Abel Grasshoppers!” As Walt writes it, “Carl decided that I was the man to design the insignia…and we’re all mighty proud of the result.” From that point on, many light planes, regardless of the manufacturer, were designated as “Grasshoppers.” That is the end of the story of Aeronca Grasshoppers. The final page is an “Identifying Those Planes” chart that shows mostly top-down silhouette views of twenty-two military aircraft. Curiously, the text-only describes twenty-one!

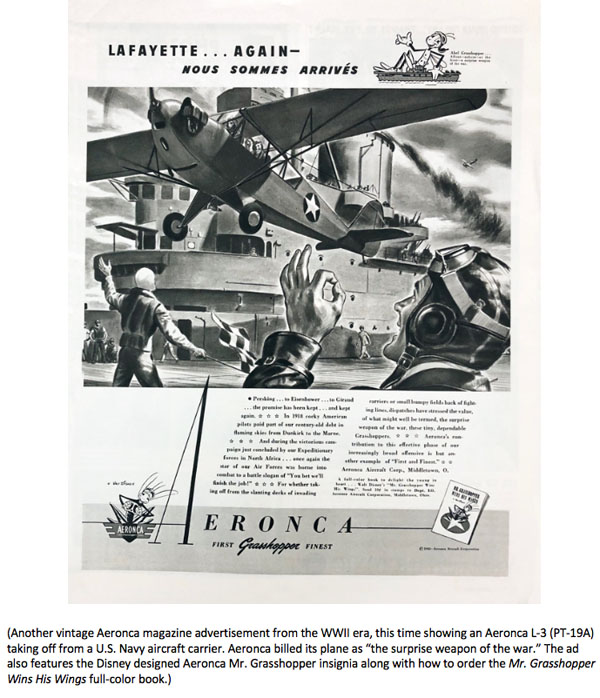

The Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings booklet is dedicated to “All American Aviators— Past, Present, Future.”(26) The booklet, “to delight the young in heart,”(27) is in full-color and was available for ten cents in postage stamps by writing to Dept. LO, Aeronca Aircraft Corporation, Middleton, Ohio. In one of at least six advertisements that Aeronca ran in large format magazines in the 1940s, they bill their plane as, “the star of our Air Forces was born into combat to a battle slogan of “You bet we’ll finish the job! For whether taking off from the slanting decks of invading carriers or small bumpy fields back of the fighting lines, dispatches have stressed the value of what might be termed, the surprise weapon of the war, these tiny, dependable Grasshoppers.”(28) The Aeronca Grasshopper airplanes made a significant mark as part of aviation history and its contribution to WWII in both the European, North Africa and Pacific theaters.

Once again, Walt Disney Productions helped with their part in creating training films to help facilitate the education of servicemen and women of the U.S. Armed Forces. At the same time, Disney gave the Grasshopper a storybook that not only entertained but inspired many young people and those “young at heart” to dream about the present and future possibilities of aviation. I wonder how many children were so encouraged by the Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings booklet that they went onto learn how to fly? We may never know, but that is the beauty of the Disney brand at its purest — it touches people in profound ways, and changes lives.

©2020 David Bossert

FOOTNOTES

1 – Bob Hollenbaugh and John Houser. Aeronca: A Photo History, Aviation Heritage Books 1993; pg. 1

2– Donald M. Pattillo. A History in the Making: 80 Turbulent Years in the American General Aviation Industry. p. 18.

3 – Bob Hollenbaugh and John Houser. Aeronca: A Photo History, Aviation Heritage Books 1993; pg. 3

4 – Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings, Aeronca publication 1943, pg. 18

5 – Aeronca sponsored magazine advertisement, 1943

6 – Letter from Walt Disney Productions (WDP) to Carl Friedlander, Pres., Aeronca Aircraft Corp., March 3, 1943; Walt Disney Archives (WDA)

7 – Letter from Walt Disney Productions to Carl Friedlander, Pres., Aeronca Aircraft Corp., March 3, 1943; (WDA)

8 – Andrade, John, U.S .Military Aircraft Designations and Serials since 1909 Midland Counties Publications, 1979

9 – Internal WDP Memo from Production Manager Dick Pfahler to Victor Bronnais, dated March 8, 1943. (WDA)

10 – Internal WDP Memo from Morty Tyler to Production Manager Dick Pfahler, April 2, 1943; WDA

11 – Letter from Hugh B. Du Valle, Headquarters, Air Services Command Technical Data Section, Maintenance Division, to Ben Sharpsteen at Walt Disney Productions., March 23, 1943; (WDA)

12 – WDP Call Sheet, Tuesday, April 27, 1943. (WDA)

13 – David Lesjak, U.S Militaria Forum Jan. 2016; and Service With Character Theme Park Press, 2014, pgs. 63, 88

14 – Authors examination of the artwork and expert opinion, which has been verified by Disney Historian David Lesjak. To the trained eye, these drawings are done by different artists.

15 – Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings, Aeronca publication 1943, pgs. 5-6

16 – Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings, Aeronca publication 1943, pg. 8

17 – Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings, Aeronca publication 1943, pg. 10

18 – Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings, Aeronca publication 1943, pg. 11

19 – Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings, Aeronca publication 1943, pg. 13

20 – Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings, Aeronca publication 1943, pg. 14

21 – Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings, Aeronca publication 1943, pg. 17

22 – Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings, Aeronca publication 1943, pg. 18-19

23 – Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings, Aeronca publication 1943, pg. 21

24 – Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings, Aeronca publication 1943, pg. 22

25 – Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings, Aeronca publication 1943, pg. 23

26 – First page from Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings, Aeronca publication 1943

27 – From an Aeronca magazine advertisement featuring the U.S. Navy version of the AeroncaL-3, 1943.

28 – From an Aeronca magazine advertisement featuring the U.S. Army version of the AeroncaL-3, 1943.

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

The “Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings” pamphlet contains some errors in its own account of Aeronca’s origins.

The company was not founded in Middletown, Ohio, but moved there after the great Ohio River flood of 1937 destroyed the Lunken Field factory. Charles Phelps Taft, the elder half-brother of President Taft, died in 1929 at the age of 86 and had nothing to do with Aeronca. It was President Taft’s elder son, future Senator Robert A. Taft, who was one of the founders of Aeronca and served on its board of directors. (As far as I know, President Taft’s younger son, future Cincinnati Mayor Charles Phelps Taft II, was not involved in Aeronca.) In 1935 the Taft family sold their interest in Aeronca to Walter Friedlander, who appointed his son Carl as president of the company. Despite having been “weaned on high octane gasoline,” Carl Friedlander was not one of Aeronca’s founders.

These might be simple slips of the pen. On the other hand, by 1943 Robert Taft was serving in the U.S. Senate; and while he supported the war effort after the attack on Pearl Harbor, before that he had been a staunch non-interventionist, resolute in his opposition to the U.S. entering the war or aiding any of the countries that were fighting Germany. So Aeronca might have wanted to downplay his erstwhile involvement with the company, instead giving credit to a less controversial member of that prominent family.

Out of curiosity, how long were these training films? And have any of them survived to the present day?

Hi Paul,

Yes, isn’t it interesting how company’s change and bend the facts. I don’t think it was a slip of the pen but the “Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings” is how Aeronca “sanitized” their history and made it what they wanted. This is more common then most think in the corporate world. “Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings” is Aeronca’s version of events and history!

There are five training films/slide films that I am aware. I am still researching the availability of these, but believe some of the slide films have survived.

Thank you,

-Dave

That wouldn’t surprise me Dave. I’m sure businesses in my town had done the same too to drum up their importance in history.

Very nicely done bit of history.

Thanks, Eric!

Very good post, Dave. I will wait with great interest to see if you locate any film material on the Aeronca Project. In 62 years of film collecting, no prints of the Aeronca films have ever surfaced. Good luck to you in your search. P.S. I wish the pages of “Mr. Grasshopper Wins His Wings” had been reproduced just a bit bigger, so we could more easily judge the interior art with Hank Porter’s cover.

Thanks, Mark!

I will see if I can get an interior image added that will allow you to look for yourself. I would value your input on my thought that the interior illustration were done by a different artist.

I’m hopeful to find at least find a film strip from the project. We’ll see…. it’s all about the hunt!!

Such same that the Basic Maintenance of Primary Training Airplanes [Aeronca Project] films have not re-surfed considering

that the some of the films according article did have “cartoon intercut.” sequences in them. But its impossible to know if all 5 films the films had such sequences in them until they resurface. I mean in the similar C1-Autopilot series of training films not all of the C1-Autopilots films have cartoony sequences in them.´