Say ‘Motion Picture’ and ‘1939’ together and images are conjured of what may be considered Hollywood’s pinnacle year, when GONE WITH THE WIND, THE WIZARD OF OZ, STAGECOACH, GUNGA DIN, WUTHERING HEIGHTS, NINOTCHKA, DRUMS ALONG THE MOHAWK, SON OF FRANKENSTEIN, THE HOUND OF THE BASKERVILLES, DARK VICTORY, OF MICE AND MEN, THE ROARING TWENTIES, EACH DAWN I DIE, BEAU GESTE, DESTRY RIDES AGAIN, IDIOT’S DELIGHT, YOUNG MR. LINCOLN, and MR. SMITH GOES TO WASHINGTON were released. To the person on the street ‘movies’ were feature length stories with attractive actors.

Say ‘Motion Picture’ and ‘1939’ together and images are conjured of what may be considered Hollywood’s pinnacle year, when GONE WITH THE WIND, THE WIZARD OF OZ, STAGECOACH, GUNGA DIN, WUTHERING HEIGHTS, NINOTCHKA, DRUMS ALONG THE MOHAWK, SON OF FRANKENSTEIN, THE HOUND OF THE BASKERVILLES, DARK VICTORY, OF MICE AND MEN, THE ROARING TWENTIES, EACH DAWN I DIE, BEAU GESTE, DESTRY RIDES AGAIN, IDIOT’S DELIGHT, YOUNG MR. LINCOLN, and MR. SMITH GOES TO WASHINGTON were released. To the person on the street ‘movies’ were feature length stories with attractive actors.

Three thousand miles away from Hollywood a very different aspect of the movie business occupied the attention of Nathan Sobel in New York. From what I can gather, Nate Sobel’s interests lay with color film processing. Sobel had some connection to DuArt Film Laboratories at 245 West 55th Street. DuArt dabbled in animation and special effects, mainly meaning optical effects. Loucks & Norling were there in the same building.

Nate Sobel also had some affiliation with Audio Productions in Long Island City, and their client Consolidated Film Industries. In 1939 Nate Sobel decided to start a company to aid little studios with production. Sobel started out small, securing a French movie camera built in 1910. Leon Levy partnered with Sobel in this enterprise. Levy handled the technical end while Sobel looked after the business. Sobel invited his brother-in-law Irving Hecht, unemployed with a teaching degree, to assist him and learn the business.

Nate Sobel also had some affiliation with Audio Productions in Long Island City, and their client Consolidated Film Industries. In 1939 Nate Sobel decided to start a company to aid little studios with production. Sobel started out small, securing a French movie camera built in 1910. Leon Levy partnered with Sobel in this enterprise. Levy handled the technical end while Sobel looked after the business. Sobel invited his brother-in-law Irving Hecht, unemployed with a teaching degree, to assist him and learn the business.

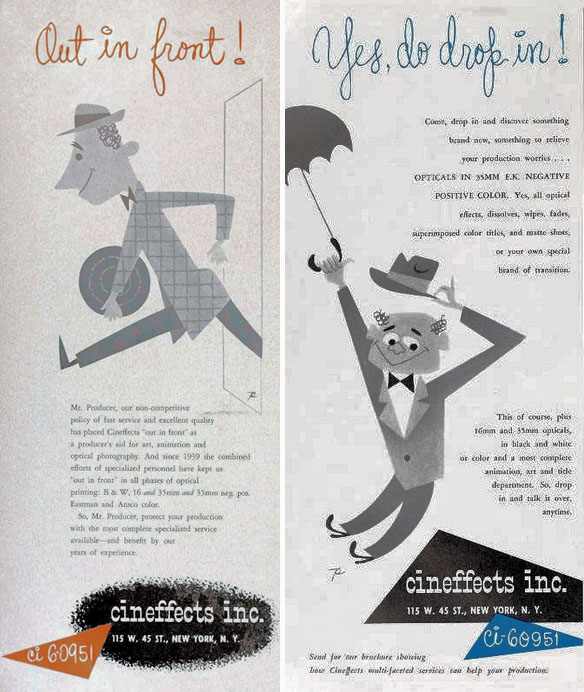

Cineffects maintained a low profile, no promotional ads in trade publications. Jobs must have come by word of mouth, but the company grew, moving twice before renting space at 1600 Broadway in the Studebaker Building. One of the guys Leon Levy relied heavily on was James Love. Born to parents who toured as a vaudeville act, James Love got into the business young. When his father settled down to manage a movie theater, while training as an assistant projectionist, Love carried films to and from the exchange on his bicycle. Warner Brothers’ booking department hired him upon graduation. In the Coast Guard James Love learned how to edit film. Together, Leon Levy and James Love hammered out problems in effects production. By 1944 the company was advertising its existence.

Irving Hecht ran the special effects department. Anne Busch supervised editing. In 1945 Al Semels was head of animation for Cineffects. Semels supported Screen Cartoonists Local 1461, which negotiated a contract with Cineffects early in 1946. Sydel Solomon, long-time inker for Max Fleischer, recently at M-G-M, came over. Animator Jimmy Tanaka came from the Fletcher Smith Studio. Tanaka had been with Disney and Famous Studios before that.

Phil Klein, who started as an inker For Van Beuren Studios, showed up. Phil had worked his way up to inbetweener before Van Beuren closed, following his older brother Izzy to Disney. Phil Klein spent four years in Hollywood learning animation and assisting in the camera department. This marked Klein as a good fit for Cineffects, where they were streamlining effects techniques into a new process. As Nathan Sobel explained:

The studio camera cannot always tell the complete story without the aid of the drawing board, the optical bench or the animation camera. Our function is to tie up the loose ends of motion picture production. The wide service we have rendered in this branch of film work has made Cineffects the foremost “Producers’ Aid” in the industry.

Sobel and Leon Levy dissolved their partnership in late 1946. Sobel incorporated Cineffects, holding onto one hundred percent of the stock. Irving Hecht became Secretary/Treasure. Sobel started a venture called Model Films at 27-27 Jackson Avenue in Long Island City with Bob Jenness. Model Films boasted of a new technique for 3-D animation, so I’m supposing they did stop-motion.

Sydel Solomon and Phil Klein left Cineffects in April of 1947. Solomon went to Tempo. Klein went to Fletcher Smith. Jimmy Tanaka went off to Transfilm. Model Films doesn’t seem to have lasted long, but Sobel was also involved with the Color Service Company and their lab at 115 West 45th Street, across from the Knickerbocker Hotel where the animators’ union sometimes met.

A fresh batch of animators rolled in during 1949. Paul Halliday had been with Fleischer two decades before, and more recently Fletcher Smith. Irv Dressler started with Fleischer in Miami and joined Famous Studios. Sylvia Alevy had been with Famous and Minitoons. Alex Geiss from Terrytoons had been with Disney before being part of Frank Tashlin’s great experiment at Columbia Screen Gems. Russ Dyson, another West Coast transplant from Disney joined Cineffects in 1950. Dick Rauh, graduate of the Art Students Leauge, had been kicking around different shops, settling into Cineffects to really learn the optical trade.

The company moved to 115 West 45th Street. James Love went off in 1952 to start his own shop, first with salesman John Lalley as Lalley 7 Love at 3 East 57th Street. Alex Geiss went along as head of animation. After five years it became simply James Love Productions, moving into the same building as Cineffects, staying until 1961 when Love moved to 2 West 46th Street with Stanley Popko as Creative Director. Six years later James Love was at 550 Fifth Avenue with a sound stage as well as recording and editing studios. He stuck around until about 1986.

The company moved to 115 West 45th Street. James Love went off in 1952 to start his own shop, first with salesman John Lalley as Lalley 7 Love at 3 East 57th Street. Alex Geiss went along as head of animation. After five years it became simply James Love Productions, moving into the same building as Cineffects, staying until 1961 when Love moved to 2 West 46th Street with Stanley Popko as Creative Director. Six years later James Love was at 550 Fifth Avenue with a sound stage as well as recording and editing studios. He stuck around until about 1986.

As James Love departed in 1952 Cineffects continued to grow. Designer Burt Freund signed on. Freund started in California under Frank Tashlin on Daffy Ditties and worked in the graphics department of CBS in New York. Young animator Ed Smith, inker Beccy Blashko, and Fleisher Studios veteran John Cuddy all came aboard in 1954. Fleischer’s writer Joe Stultz passed through at some point.

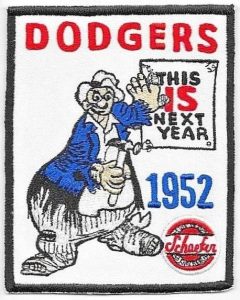

Schaefer Brewing sponsored televised broadcasts of the Brooklyn Dodgers games in those days. Cineffects made Schaefer’s beer commercials. Some were stop-motion bits where the bottle caps seemed to be talking. There were others featuring the Schaefer mascot, an unkempt fellow named Thirsty. Animator Thurlo Collier left Terrytoons for Cineffects in 1955 to reinvent himself as an optics man.

Schaefer Brewing sponsored televised broadcasts of the Brooklyn Dodgers games in those days. Cineffects made Schaefer’s beer commercials. Some were stop-motion bits where the bottle caps seemed to be talking. There were others featuring the Schaefer mascot, an unkempt fellow named Thirsty. Animator Thurlo Collier left Terrytoons for Cineffects in 1955 to reinvent himself as an optics man.

Nathan Sobel’s old partner Leon Levy operated Film Opticals at 421 West 54th Street, pushing the boundaries of optical effects. Sam Levy, once a cameraman at Cineffects, started Eastern Effects at 333 West 52nd Street and Dick Rauh went over there. Both these studios were at the forefront of developing new optical techniques. Optical workers had no union of their own, so the Screen Cartoonists Guild invited them in.

Cineffects employed fifty-one people by 1955, twenty of them in the animation department. The only theatrical cartoon I’m aware of the company making is Killjoy Was Here!, sponsored by the U.S. Air Force Photographic and Charting Service. The character of killjoy was voiced by Jackson Beck, better known as Popeye’s nemesis Bluto. Izzy Klein directed the cartoon, which is embed at the bottom of this post.

Six people in the machine shop were often called upon to modify equipment to achieve some new effect. Cineffects used top of the line Oxberry animation equipment. An important technical advancement came about when Oxberry Products manufactured a new rostrum camera. Improvements included special frame counters, and special pin-registers to keep film from jumping track when doing double exposures. Such attention to excellence led to Cineffects winning accolades in 1957 for a deodorant commercial where a woman splits in half while walking down street.

Six people in the machine shop were often called upon to modify equipment to achieve some new effect. Cineffects used top of the line Oxberry animation equipment. An important technical advancement came about when Oxberry Products manufactured a new rostrum camera. Improvements included special frame counters, and special pin-registers to keep film from jumping track when doing double exposures. Such attention to excellence led to Cineffects winning accolades in 1957 for a deodorant commercial where a woman splits in half while walking down street.

Al Semels was doing alright for himself. He’d left Cineffects several years before to work for Lee Blair at Film Graphics, then Dave Hilberman at Tempo Productions, and Chad Grothkopf at Chad Associates. He started Anifilm Studios at 165 West 46th Street around 1957, and soon added the Albert Semels Studio at the same address. Ray Favata Productions moved into the building around the same time as Gifford & Kim in 1960.

Nathan Sobel died in 1962. Irving Hecht (shown here in a sketch by Izzy Klein) took over as president and carried on, continuing to enlarge the studio. When the real estate company Income Properties, Incorporated acquired Cineffects in 1967 the place had eighty-five employees, expanding into another 4,500 feet of their building. By 1970 Cineffects occupied five floors of 115 West 45th Street.

Nathan Sobel died in 1962. Irving Hecht (shown here in a sketch by Izzy Klein) took over as president and carried on, continuing to enlarge the studio. When the real estate company Income Properties, Incorporated acquired Cineffects in 1967 the place had eighty-five employees, expanding into another 4,500 feet of their building. By 1970 Cineffects occupied five floors of 115 West 45th Street.

They hung on for another decade. Cineffects Color Laboratories, Inc. made SEA ISLAND for the South Carolina Arts Commission in 1977.

In 1979 they were listed as Cineffects Visuals, then the trail goes cold. GONE, BUT NOT FORGOTTEN. Cameraman Al Schirano had been Cineffects union delegate thirty-two years before. Schirano put what he learned there to good use at Transfilm, Academy Pictures, Hal Seeger’s shop and L&L Animation. In the Seventies Schirano operated the animation camera for Larry Lippman at Design Effects., eventually founding Schirano Camera at 45 West 45th Street.

Though it had gone quietly about its business, Cineffects set off an echo that resonated through the New York animation studios.

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

Thanks, Bob, for this expert summary on Cineffects.

I wrote a post on Killjoy a few years ago but you found out a lot more. I appreciate your thoroughness.

The bits and pieces I cobbled together are here: https://tralfaz.blogspot.com/2017/11/tralfaz-sunday-theatre-killjoy-was-here.html

Yowp

I’m a big fan of Tralfaz.

There is a Cineffects in Australia today, based at Fox Studios in Sydney. It’s a film production company offering clients in both the public and private sectors much the same range of services as Cineffects in New York did years ago, including 2D and 3D animation. I’ve seen the New York outfit referred to as “Cinefex” by writers who were clearly confusing it with the late film journal of that name.

I didn’t know that Phil Klein was I. Klein’s brother. Phil was co-chair of the pickets during the Disney strike of 1941, and he also painted signs and banners for rallies supporting Henry A. Wallace’s 1948 presidential campaign. Because of this he was investigated and harassed by the FBI and the HUAC during the Red Scare of the ’50s. Thus Cineffects, like Tempo and Transfilm, seems to have been a haven for artists who, because of their past political activities, would have been personae non gratae at the major animation studios.

Phil is Izzy’s younger brother according to Howard Beckerman, who knew them both well. Cineffects was one of first shops to join the union, so always a hot-bed of “radicala”. They gave coffee breaks early on. Tempo is a whole story I’ll get to soon.

Was Izzy Klein still working at Famous/Paramount Cartoons Studios when he directed “Killjoy Was Here” or did he leave?

Izzy Klein was part of a mass firing at Famous in Sept. ’54 (along with longterm vets like William Henning and Irv Spector), so this probably was his next job.

This is a great article Bob! Thanks for the info!

This “Killjoy” short must have been a case of the job going to the lowest outside contractor. The USAF not only had its own 2D animation unit but went so far as to use its own proprietary three hole peg registration system.