By the end of 1970 Osamu Tezuka was gone, leaving the wreckage of Mushi Productions behind him. It was no secret that Tezuka’s feature Cleopatra had doomed the studio; but there were two other reasons that Tezuka had given up on Mushi Productions. One in particular, although it was entirely his own fault, made Tezuka disgusted with the Mushi mess.

By the end of 1970 Osamu Tezuka was gone, leaving the wreckage of Mushi Productions behind him. It was no secret that Tezuka’s feature Cleopatra had doomed the studio; but there were two other reasons that Tezuka had given up on Mushi Productions. One in particular, although it was entirely his own fault, made Tezuka disgusted with the Mushi mess.

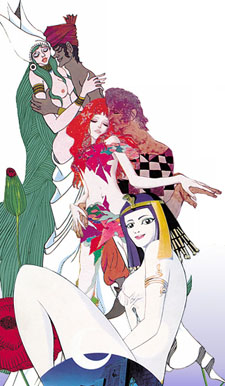

To digress somewhat, Tezuka always had the bad habit of knowingly taking on more work than he could possibly deliver upon. He was also personally more interested in experimental animation and comics than in the juvenile manga & anime that paid his bills. In October 1988, just before he died, Tezuka wrote a brief essay about his life’s work in which he said that his personal goal in creating Mushi Productions and making the 1962-1966 Astro Boy TV series had been to finance his experimental animation. Also, by the late 1960s “adult” manga had begun appearing in Japan, emphasizing mature themes of crime, war, homosexuality, psychoanalysis, passion, obsession, eroticism, and so on. The attitude grew that this was the modern evolution of manga. Manga for children – notably Tezuka’s manga – was passé. Tezuka did not like being sidelined, and determined to prove that he was not washed up. The popular failure of his Animerama theatrical features must have been more than just a financial disappointment to him. Mushi Prod.’s continued future would be to grind out more same-old children’s TV cartoons. Tezuka was an artist first and a businessman second. He did not want a creative millstone around his neck.

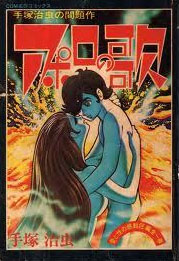

“Apollo’s Song”

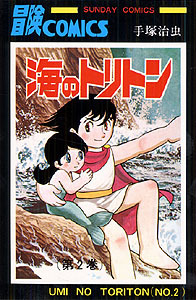

Returning to the end of Mushi Productions, the more personal reason that Tezuka left his creation was the betrayal of one of his sales managers, Yoshinobu Nishizaki (1934-2010). Nishizaki joined Mushi Prod. in 1970. At that time one of Tezuka’s jobs was to create new story concepts for Mushi to produce, and two ideas that he came up with were Triton of the Sea (Umi no Toriton) and Little Wansa (Wansa-kun). As was usual, Tezuka conceived of these as manga that he would personally write/draw, to be followed by a TV animated series that Mushi Prod. would produce. The manga was always Tezuka’s sole responsibility. The TV production had to be registered by Mushi Productions. The TV copyright registration required the name of the creator/producer. Tezuka, who was then fully occupied with the production of Cleopatra, trusted Nishizaki to file the anime copyright registration.

Wikipedia says, “Nishizaki produced his first anime, Triton of the Sea, in 1972, and followed it up with the ambitious musical comedy Wansa-kun in 1973; both were based on Tezuka manga, but due to an apparent copyright mixup on Nishizaki’s part, Tezuka lost the rights to the anime versions of both series, and Mushi Production made both shows without Tezuka’s involvement.” Dr. Tezuka told me that there was no copyright mixup. Nishizaki took Tezuka’s name off of the copyright forms and substituted his own. He reasoned that everyone at Mushi except Tezuka knew that Cleopatra was going to be a failure; that Tezuka was showing less and less interest in Mushi Productions; and that Tezuka was unlikely to redevelop enough interest to fight Nishizaki to take the properties back. More significantly, Tezuka was aware that everyone at Mushi Prod. knew what had really happened, and that most of them didn’t care. They considered that it was basically Tezuka’s fault for letting his properties be stolen from under his nose.

This is Dr. Tezuka’s own view of what happened. Again he was quivering with anger when he told me about it in 1979. In any case, it was no secret and was widely discussed in the Japanese professional animation community, with opinions divided as to whether Nishizaki was a traitor who had hastened Tezuka’s departure and Mushi’s going out of business, or a hero who had fought off Tezuka’s disinterest and kept Mushi going for a little longer. Nishizaki apparently predicted Mushi’s staff’s disinterest correctly.

This is Dr. Tezuka’s own view of what happened. Again he was quivering with anger when he told me about it in 1979. In any case, it was no secret and was widely discussed in the Japanese professional animation community, with opinions divided as to whether Nishizaki was a traitor who had hastened Tezuka’s departure and Mushi’s going out of business, or a hero who had fought off Tezuka’s disinterest and kept Mushi going for a little longer. Nishizaki apparently predicted Mushi’s staff’s disinterest correctly.

Triton of the Sea (27 episodes, April 1 – September 30, 1972) and Little Wansa (26 episodes, April 2 – September 24, 1973) were animated by Mushi Productions with Yoshinobu Nishizaki listed as producer. (For some reason, Nishizaki used the name Yoshinori Nishizaki as producer of Little Wansa, causing some to think that he was trying to disguise himself as a nonexistent brother; but everyone knew that it was the same person. Nishizaki’s birth name had been Hirofumi Nishizaki. The Japanese find it easier to change their names than Westerners. Two well-known examples in the animation and manga industries are Rintarō, born Shigeyuki Hayashi, who is also sometimes known as Kuruma Hino; and Shōtarō Onodera, who became first Shōtarō Ishimori and then Shōtarō Ishinomori.)

Little Wansa was unusual because Tezuka had originally created the tiny white cartoon Akita puppy as the mascot for the Sanwa bank chain – “Wansa” is “Sanwa” pronounced backwards – and Sanwa was the hoped-for TV cartoon’s sponsor. Wansa was frequently shown in Tezuka’s unfinished manga and in Nishizaki’s TV cartoons as cutely pissing on a fire hydrant, a tree, the side of a house, or anything else – he was supposed to have become a stray dog before he was housebroken.

The TV cartoon, directed by Eichi Yamamoto, had a memorably lively theme song by Hiroshi Miyagawa, with all of the dogs dancing a Charleston including the unhousebroken Wansa-kun. Little Wansa was Mushi’s final TV production before the studio declared bankruptcy. After Mushi Prod. closed, the staff went their separate ways. Nishizaki created his own Animation Staffroom studio, with many ex-Mushi employees (and, according to rumor, a lot of Mushi’s production equipment), and created the much more successful Space Battleship Yamato (Uchu Senkan Yamato), also with a memorable theme song by Hiroshi Miyagawa.

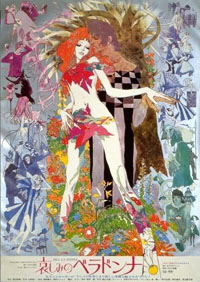

And what about Mushi’s third and final Animerama theatrical cartoon, the third and last of “Tezuka’s adult features”? Of course, Tezuka had virtually nothing to do with it. He may have created the basic concept of three Animerama features, but by the time that Mushi Prod. had finished production of Cleopatra and was ready to move on to #3, Belladonna of Sadness (Kanashimi no Belladonna – I am not the only one to think that it should’ve been called The Tragedy of Belladonna in English, rather than translating the title literally), Tezuka had left the studio, everyone knew that Mushi Prod. could no longer afford to develop and produce a theatrical feature, and there was serious doubt that it could be finished before Mushi Prod. declared bankruptcy and closed. Some critics have theorized that the “of Sadness” subtitle was chosen more because that was the mood of the animators; they knew that they were working on Mushi Prod.’s final production.Why, then, did Mushi Prod. go ahead instead of cancelling it? Partly pride. It had been announced. It kept Mushi in theatrical production rather than just lowly TV cartoons. It meant that Mushi would go under more spectacularly than slowly disappearing with less and less memorable TV productions. Partly because to the public, Tezuka and Mushi Prod. were synonymous, and Tezuka would not bother to cancel it. Partly to keep Mushi’s animators employed. Its staff had been increased significantly for the production of Cleopatra, and there was not enough other work left for everyone to do.

Eichi Yamamoto, who had been the director of the Kimba the White Lion TV series and the co-director of Cleopatra, became the sole director of Belladonna of Sadness. It was co-written by Yamamoto and Yoshiyuki Fukuda; the animation director was Gisaburo Sugii; the art designer was Kuni Fukai; the music was symphonic ‘70’s rock/jazz by Masahiko Satō. It was based upon La Sorcière by Jules Michelet (1862), a fictionalized study of medieval Satanism and witchcraft; though scholars considered it simplified and sensationalized. Wikipedia’s summary is, “According to Michelet, medieval witchcraft was an act of popular rebellion against the oppression of feudalism and the Roman Catholic Church. This rebellion took the form of a secret religion inspired by paganism and fairy beliefs, organized by a woman who became its leader. The participants in the secret religion met regularly at the witches’ sabbath and the Black Mass. Michelet’s account is openly sympathetic to the sufferings of peasants and women in the Middle Ages.”

Belladonna of Sadness

Belladonna may not have had any “Tezuka touch”, but it remained true to his goal of animation that presented themes of adult, mature eroticism that were not pornographic. It was a much more serious film than Tezuka’s comedies. Since Mushi Prod. could not afford to produce a theatrical feature, art designer Kuni Fukai developed it as a progression of still psychedelic art drawn in the styles of Aubrey Beardsley, Gustav Klimt, and other artists of the 1890s and early 20th century, and medieval-renaissance tarot-card art, with a minimal amount of animation. It was presented as an avant-garde intellectual fine-art film. It was finished barely in time; Mushi Prod. actually declared bankruptcy a few days before its release on June 30, 1973. The distributor, Nippon Herald, gave it only a ten-day run. It had been entered for competition at the 23rd Berlin International Film Festival, June 22-July 3, 1973, which fortunately coincided with its brief release. It did not win any award, and it was a commercial failure due to its short release and its lack of animation. But at least Mushi Production Company went out with a grand finale.

(Unfortunately for a dramatic ending, the bankruptcy proceedings took another four years. In 1977, Mushi Prod. resumed operations under new management, but it was an entirely new company with a different staff. It is still in business today, doing more animation subcontracting for other studios than producing its own films; but it does release an occasional feature.)

Fred Patten (1940-2018) was an internationally respected comics and animation historian. He has written about anime or comic books for publications ranging from Animation Magazine and Alter Ego to Starlog. He was a contributor to The Animated Movie Guide (2005), and is author of Watching Anime, Reading Manga (2004, Stone Bridge Press), a collection of his best essays, and Funny Animals and More (2014, Theme Park Press), based upon his early columns here on Cartoon Research. He passed away on November 12th, 2018.

Fred Patten (1940-2018) was an internationally respected comics and animation historian. He has written about anime or comic books for publications ranging from Animation Magazine and Alter Ego to Starlog. He was a contributor to The Animated Movie Guide (2005), and is author of Watching Anime, Reading Manga (2004, Stone Bridge Press), a collection of his best essays, and Funny Animals and More (2014, Theme Park Press), based upon his early columns here on Cartoon Research. He passed away on November 12th, 2018.

Mushi also did work for America’s Rankin/Bass during its final years. They animated “Frosty the Snowman”, “Reluctant Dragon & Mr. Toad”, “Festival of Family Classics”, and “The Mad, Mad, Mad Comedians”

I was going to say the same thing; Anyone here know who at Mushi besides Osamu Dezaki (who was the animation director on Frosty, any idea what other Rankin/Bass projects he worked on?) that worked on said Rankin/Bass projects? The same goes with Toei’s efforts with them as well.

Someone here needs to do a article about Toei’s & Mushi’s contracts with Rankin/Bass before Topcraft was founded.

you would think that backstabbing Osama tezuka would be career suicide. how on earth did nishizaki continue to find work in anime?

I think it was something akin to Don Bluth splintering from Disney in the late 1970s.

It seems by this time Tezuka’s reputation in the animation industry during and after the Cleopatra debacle was increasingly polarized (business-wise) and that Nishizaki didn’t have to go very far within the studio to find dissenters that could see the writing on the wall and willing to find a more long-term job security. Much like Disney when it was at its pre-Eisner low ebb and its days as an active production studio seemed numbered. No doubt there were also many disgruntled stockholders ready to back another horse.

Space Battleship Yamato, pretty much (of course that almost failed to be managed to catch on sooner or later). Smart guy I would give him that though not smart enough to run from the law later on.

http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yoshinobu_Nishizaki

Hard to imagine anyone thinking that Tezuka’s work was only meant for children. I can’t help but think of how no one liked Van Gogh’s stuff till he was dead. Time really changes things.

Isn’t that true of any artist, really? It’s a vicious cycle.

I’m just going to leave this link here as I’m sure for anyone delayed onlookers to this page might have a chance to check it out before it’s gone.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=di34OYJcQO0

IMDB lists Akio Sugino and Sadao Miyamoto were animators on Frosty but I am not sure if this is right

CORRECTIONS AND ADDENDA:

– The credited studio of Triton was Animation Staff Room, a studio formed early in 1972 by ex-Mushi people, and available subcontractors/freelancers.

– Wansa was actually animated by the remnants of Mushi and other subcontractors/freelancers Nishizaki could find.

– Animation Staff Room didn’t take part in the production of any Space Battleship Yamato anime. The enigmatic studio itself existed until 2011.

– Nishizaki did create a new main studio for Space Battleship Yamato.