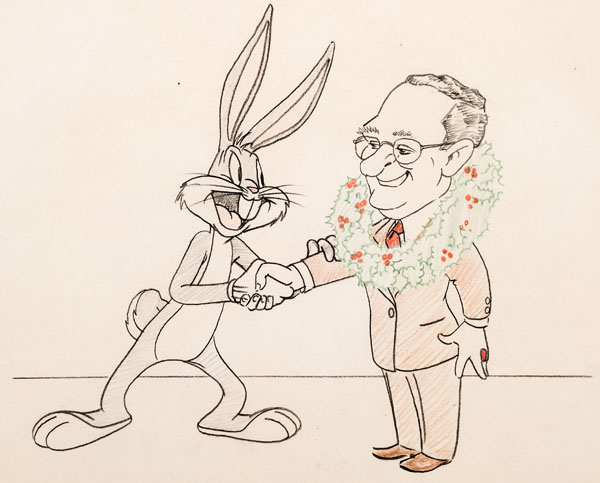

Bugs Bunny congratulates his boss, Ed Selzer, in this drawing by Robert McKimson

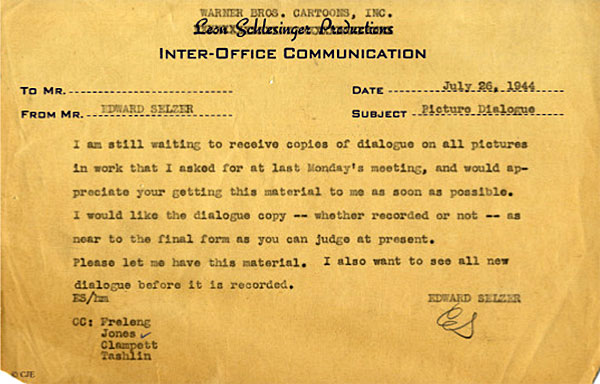

There really hasn’t much written about Warner Bros. cartoon producer Edward (Eddie) Selzer. Jerry Beck posted Selzer’s official studio bio in this post back in 2013. Readers of Chuck Jones’ two volumes of memoirs might well be forgiven if a negative impression of Selzer is formed by what’s written there. Certainly, when I wrote The Warner Bros. Cartoon Companion some years ago, I relied on Jones’ point of view, and was, at one point, brought up short by descendants of Selzer who took issue with the portrayal. Even if, as the interoffice memo below shows, Selzer’s grasp of animation may have been shaky at the start of his career.

This is not to say that Selzer was always treated roughly. The September 1948 issue of the in-house magazine of Warner Bros. Warner Club News carries an article on Selzer written by Treg Brown (the sound-effects and editing wizard behind the cartoons); this article was pointed out to me by historian Devon Baxter, after I had posted some ancestry.com materials relating to Selzer on Cartoon Research’s Facebook page. In reading this article, and comparing it to some other materials I found on ancestry.com, a few somewhat surprising facts turned up, which are (perhaps) worth going into in a bit of detail. Since the article contains, more or less, a miniature biography of Selzer, I will go through that, with annotations and commentary by me.

by Treg Brown

Thumbnail sketch of Edward Selzer

“And, in this corner at one hundred and nine pounds, Edward Selzer!”

The occasion was the championship bout, bantam weight division, New York State amateur boxing in 1914. At the end of the fight the referee raised the hand of Edward Selzer, “The winner and champion!” It was his 27th win, 21 of which were by the K.O. route, and 18 of these in the first round. […]

As we will see later on, there’s a good deal of truth in what Brown writes here – but one very curious change. As to Eddie’s fight record, I have found no specific data, though there are some suggestive reports that indicate it could well be accurate.

As will be evident shortly, Brown here is referring not to the first Louis-Walcott fight of December 5, 1947, which Louis won in a highly controversial decision, but to the rematch, won by Louis, on June 25, 1948.

[…] There were three of us in the office after hours, John Burton, myself and Mr. Selzer. […]

John W. Burton would go on to succeed Eddie Selzer as head of the cartoon studio when Selzer retired in 1958. As of 1948, he was the production manager at Warner Bros. Cartoons.

[…] Somehow the talk got around to the coming fight between the two Joes and Mr. Selzer said “Louis will take Walcott this time.”

As I watched him explaining the reasons for his statement I noticed he was using his mitts as though he’d been at least on speaking terms with the noble art of self defense. When I mentioned this Johnny smiled kind of knowing like and said, “I thought you knew.”

“Knew what?” I asked. After all, I’ve known Mr. Selzer for a long time, in fact, I used to cut music and sound for his trailers and shorts over on the main lot.[…]

As noted below, after being director of West Coast publicity for Warner Bros., Selzer was a special assistant to Bryan Foy, and was in charge of trailers from 1937 until 1944.

[…] “Well, then,” Johnny said, “you’ve got a surprise coming.”

That surprise I’m going to pass on to the rest of you even though it has taken me about six months to pry the story loose from the boss.

It starts back in New York’s Lower East Side, Clinton Street, on the 12th of January, 1893. (There’s a song that goes “East Side, West Side, All Around the Town” which brings to mind a couple of other boys who grew up in that neighborhood – fellows called Al Smith and Eddie Cantor – or was it Walter Winchell?) That’s when and where Mr. Selzer was born, and where for a little over ten years the Selzer family grew up. […]

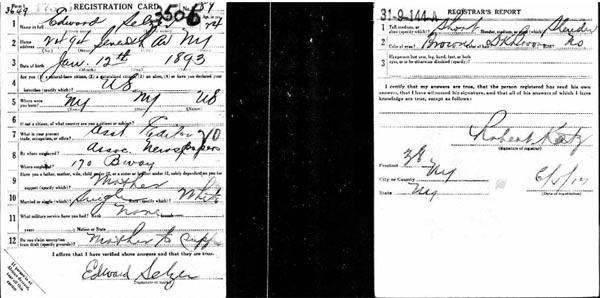

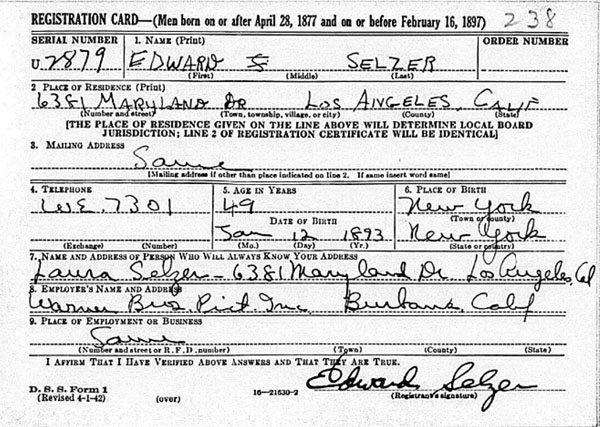

I have not been able to locate Edward Selzer’s birth record (possibly because that was not his birth name), but the January 12, 1893 date does match the information he provided to the government on his World War I and World War II draft registration cards.

[…] They moved from the city to a farm in New Jersey where they lived for a year and a half. (The only member of the family who still takes to farming is Mr. Selzer’s brother Mike, who owns and operates a large chicken farm in Laurel, Delaware. The other, Dr. J. Selzer, is a dentist in New York.)[…]

While I have not been able to trace any materials showing when and where, precisely, the Selzer family lived in New Jersey, the statements regarding Eddie Selzer’s two brothers are accurate, based on multiple items of census and military data. Joseph Selzer (1890-1967) was born in the Russian Empire – one immigration document lists his village as “Barawock,” though his World War I draft registration refers to Minsk, in present-day Belarus. Michael Selzer (1895-1953) appears to have been born in New York City like his elder brother Eddie. The 1910 census data indicates that Annie B. Selzer (Eddie’s mother) and his elder brother Joseph came to the United States in 1891.

[…] After the death of their father, the family moved back to New York City where Mrs. Selzer bought a place of business in Little Italy, in Harlem. […]

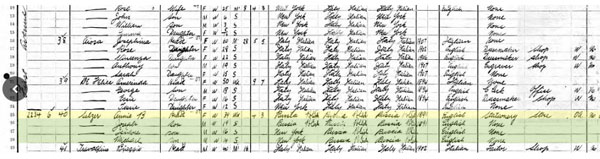

As of the 1910 census, the Selzer family lived at 2234 1st Avenue, at the corner of 1st Avenue and East 115th Street, which is squarely in the heart of East Harlem, and Italian Harlem, and a block from Thomas Jefferson Park (which I will get back to shortly). Mrs. Selzer’s profession is listed as running a stationery store.

[…] It was there that the young Edward was forced to use his fists, and as he told me, it was “at least one fight a day with two on Sundays for the first year!” It was a tough neighborhood as Mike Maltese can attest. […]

Mike Maltese being, of course, the writer on staff at Warner Bros. Cartoons. Born in 1908, as of the 1910 census, his family lived at 67 West 100th Street, about two miles west of where the Selzer family lived. Not unreasonable that Maltese would know the area.

One curious bit of data in the 1910 census may indicate why young Eddie was forced to fight so often. Instead of “Edward” or “Eddie,” his name is listed as “Isidore.” While I do not have any positive proof, this does suggest that the Selzer family was Jewish, which would readily explain the constant clashes with local Italian/Catholic toughs. The question of his given name will crop up again.

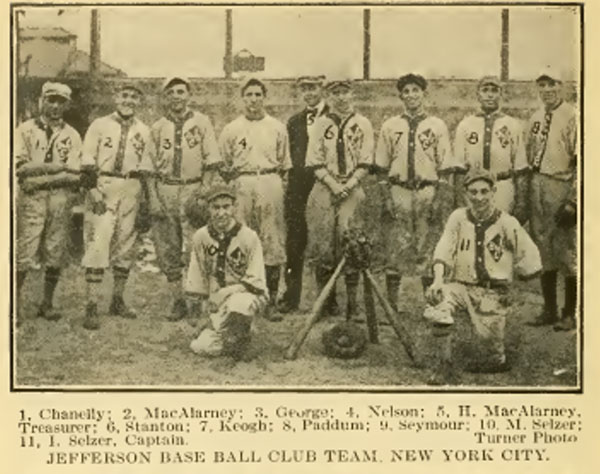

[…] So it was a ‘natural’ for a kid who knew how to take care of himself to move into other competitive fields. Baseball and basketball offered adventure and he captained and managed both teams, continuing in baseball for nine years. […]

There is solid evidence with respect to Selzer being a baseball captain. The 1913 edition of Spalding’s Official Metropolitan Baseball Book carries information regarding teams (in different classes) representing Thomas Jefferson Park in a tournament held that year. Thomas Jefferson Park, it will be recalled, was a block from where the Selzer family lived.

One of the teams representing the park not only has an “I. Selzer,” but an “M. Selzer,” quite possibly Eddie Selzer’s younger brother Michael. The Spalding guide carries a team photo, showing “I. Selzer” as the captain. For comparison purposes, I’ve included a closeup of “I. Selzer” with a known, 1954 photograph of Eddie Selzer, and I invite readers to make their own judgements on the matter. Personally, I think it’s him.

Not mentioned in Brown’s article, but referred to in an official Warner Bros. biography reproduced at Cartoon Research in 2013, were the facts that Selzer studied advertising at New York University (at some unstated date, presumably before 1914), and began his career at the New York Globe newspaper (again, presumably before 1914). The official biography notes that Selzer worked for Associated Newspapers from 1914 to 1930; that organization will be referred to, below.

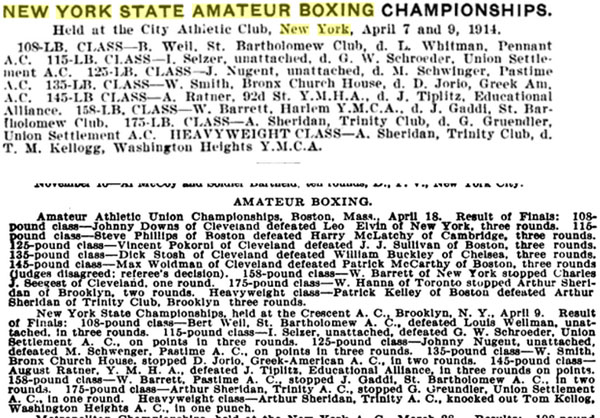

[…] In 1914, Mr. Selzer began boxing in the amateur ranks, winning his first tournament by scoring three knockouts in four bouts. It was during this tournament that he injured his hand for the first time, an injury which was later to keep him out of the Olympics. […]

The 1916 Olympics had been projected to be held in Berlin, and prior to June, 1914, that event was still going forward.

[…] In the winter of 1914 he won the New York State bantam weight championship and thereby the opportunity to compete for the Olympics. However, when the doctor finished examining the new champ and found an injured nose and a broken left hand, he told him to hang up his gloves. […]

The New York Times wasn’t known for its detailed coverage of amateur boxing in this era, but there is a fair bit of evidence showing the arc of Selzer’s career, and undeniable evidence that Selzer was indeed the bantam weight champion of New York. Many online references to Selzer (including Wikipedia, as of this writing) claim he fought in the Golden Gloves tournament, but that tournament did not start until some years after Selzer had stopped boxing, the first tournament being held in March, 1927.

The January 11, 1914 edition reports as follows: “I. Selzer, unattached, was awarded the decision over V. Allen of the Mott Haven A.C. in the final of the 115-pound class in a rather tame three-round session. Both boys were crude in their work, neither showing any particular knowledge of boxing. On the whole Selzer was the better, and what few clean blows he landed were recorded in his favor. He tried to use a left jab but lacked proficiency and missed more often than he scored. Both were inclined to hug with the result that fast work was lacking.”

And yet, in spite of this, almost exactly three months later, on April 10, 1914, the Times, in reporting on the state championships, said the following: “The semi-final and final bouts in the State boxing championships were decided last night in the City Athletic Club gymnasium. The result was a series of exceptionally interesting contents, which brought out several New York State candidates, who will participate in the national championships at Boston. […] An even better contest resulted in the meeting of Selzer and Mass in the 115-pound class. There was not an idle second, the boys putting up a bout worthy of professionals. In the second round, because of a claim by Mass that Selzer had butted him the bout was stopped until the club’s physician examined Mass and reported him uninjured. The contest was then resumed and Selzer won after a hard struggle. [Later in the article, it’s noted that it was a referee’s decision – EOC] […] [t]he final of the 115-pound class was won by Selzer, who defeated Schroeder after a rattling contest. [Noted in the World Almanac as being a decision on points – EOC]”

Evidently, in just three months, Selzer’s skills had improved to the point where he was crowned the bantam weight amateur champion of New York State, as both the 1915 editions of the Spalding almanac, and The World Almanac show. I did not find any indication that Selzer fought in the A.A.U. boxing championships, which were held in Boston on April 17th and 18th, though if Selzer had injured his hand, it’s highly likely he would not have competed.

Contrary to the impressions given in the Warner Club News article, though, Selzer does appear to have fought some more at various times in 1914 and 1915. The December 17, 1914 edition of the Times noted that “E. Seltzer [sic – EOC], Hamilton Lyceum, State 115 pound champion, stopped Joseph Curley, East Side House, in one round […] Seltzer won the first final bout, defeating Friedman in the 108-pound class after an extra round had been ordered.” Previously, on December 15th, the Times had reported “E. Seltzer [sic – EOC] defeated J. Butch, unattached, Referee stopped bout in the first round.”

Contrary to the impressions given in the Warner Club News article, though, Selzer does appear to have fought some more at various times in 1914 and 1915. The December 17, 1914 edition of the Times noted that “E. Seltzer [sic – EOC], Hamilton Lyceum, State 115 pound champion, stopped Joseph Curley, East Side House, in one round […] Seltzer won the first final bout, defeating Friedman in the 108-pound class after an extra round had been ordered.” Previously, on December 15th, the Times had reported “E. Seltzer [sic – EOC] defeated J. Butch, unattached, Referee stopped bout in the first round.”

Note that some time between April of 1914, and December of 1914, “I. Selzer” became “E. Selzer.” It is obviously the same person, given the reference to the 115-pound champion status.

The March 14th, 1915 edition of the Times was the last reference I found to Selzer’s boxing career. Alas, it is not a positive one. Reported the paper, with respect to the intercity amateur boxing tournament: “Ed Selzer of the Hamilton Lyceum, New York State champion, and M. Johnstone, Pittsburgh A.A., Middle Atlantic A.A.U. title holder, were the finalists in the 108-pound class. The ring tactics of the local amateur did not please the spectators and they showed their disapproval. Johnstone received the decision on clean work, the verdict being loudly applauded.”

Selzer’s record of knockouts is unclear, though he seems to have scored quite a few: what is absolutely undeniable, though, is that he was indeed an amateur boxing champion.

Back to the Warner Club News article.

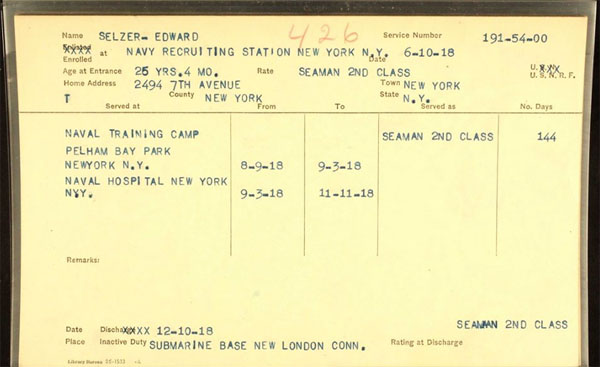

[…] This [i.e., hanging up his gloves – EOC] he did for three years, digging them out only because he wanted to represent his regiment training at the Pelham Bay Naval Training Station. […]

I’ve omitted a few paragraphs about the fighting (including fighting with a cold, and a reference to the Spanish Influenza which I’d rather not get into right now, current events being what they are), but there is evidence to back Selzer’s presence at the Naval Training Station.

As can be seen, Selzer was not at the training camp for very long – less than a month – and was then at a naval hospital in New York. One can speculate that he had contracted the influenza. The 7th Avenue address listed for him is the same address listed on his 1917 draft registration card. He appears to have been drafted, not having enlisted; he had claimed an exemption based on his mother’s status in his 1917 registration.

[…] The end of the war found him stationed at the U.S. Marine base in New London, Conn. The day after he was released from active duty returned to his job with the Associated Newspapers as business manager. […]

As can be seen from above, Selzer was discharged at the submarine base in New London, not a U.S. Marine base. His 1917 draft registration had listed him as an assistant editor at Associated Newspapers, 170 Broadway, New York. Advertisements in early 1920 editions of Editor and Publisher describe its feature service; it had been formed in 1912 as a consortium of a few newspapers, including the New York Globe, where Selzer had started, and among other things, distributed a few comic strips. It was acquired by the Bell Syndicate at some point in 1930.

Omitting material related to Selzer’s 1927 marriage to the former Laura Cohn, and to his two children, we pick up with 1930.

[…] In 1930, the late Lewis Warner, son of Harry Warner, persuaded Mr. Selzer to join Warner Bros. to work on Bob Ripley’s “Believe It Or Not” series of shorts, an also, believe it or not, to start an animation unit. […]

Query if the acquisition of Associated Newspapers, and/or the effects of the October, 1929 crash had convinced Selzer to change jobs. It is unclear which event came first. The first Ripley short had its copyright registered in June of 1930, and was reviewed in various trade papers in May of 1930. It should be noted that Associated Newspapers had been the syndicator of Ripley’s comic strip from 1924 to 1929, when King Features acquired the rights to the strip.

[…] When the bottom fell out of the picture business in August of 1930 he was transferred to the Publicity Department while still continuing on the Ripley shorts, to writing publicity for the Warner Bros. pictures appearing on Broadway. Then when Warners and First National merged, he was assigned to write and plant publicity for First National pictures playing in New York. […]

There’s no other indications of Selzer’s putative role in animation that has come to light – presumably, as he was based in New York City, the studio would have been based there. Lewis Warner, who had been touted as the heir apparent to the business, died in 1931 from pneumonia complications relating to an infected tooth. 1930 was a bad year for Warner Bros., as a number of its musical films, in which it had invested heavily, did poorly, and the costs of many of its acquisitions weighed heavily.

On his return to New York [in 1931, from a trip abroad with Robert Ripley, description omitted – EOC], he continued working but in addition handled the publicity for the trade papers and was in charge of the ‘press book’ department. [Description of Selzer being in charge of the “Forty Second Street Special” promotional train omitted; a noteworthy publicity stunt of the era underwritten by General Electric.] Right on the heels of this [i.e., the train in 1933 – EOC], came a promotion to the head of the Publicity Department of Warner Bros. studio in Burbank, a job which he held until he was put in charge of trailers and main titles in 1937.

The October 5, 1937 edition of the New York Times noted that Selzer, “for four years with Warners as head of West Coast publicity, swings over as general assistant to Bryan Foy at the same studio.” Foy (1896-1977), at this time, was the head of the “B” movie unit at Warner Bros., and had previously been involved in producing and directing Vitaphone shorts for the studio.

[…] Mr. Selzer’s last promotion came in July, 1944 when he was made president of Warner Bros. Cartoons, the position he now fills. […]

The article by Brown concludes with Selzer expressing how thrilled he was when Tweetie Pie won the Academy Award for 1947 in March, 1948. (A rare tiny clip of that can be seen here. Selzer’s speech that evening included heartfelt thanks to the whole staff and a particular nod to Friz Freleng – read it here).

The impression I get is that significant portions of the Warner Club News sketch of Selzer can be independently verified; I believe the 1912 photograph of Selzer for the Jefferson Park baseball club is one of the earliest photographs of him available online, and has not previously been pointed out. The question of whether his birth name was Isidore Selzer is an intriguing one, and one I plan on pursuing if I can. Also worthy of further research is Selzer’s role with respect to the 1933 “Forty Second Street Special” train, which may well have been one of the highlights of his pre-cartoon career.

E.O. Costello is a New York-based attorney, whose love of history has led him to study, in depth, the cartoons of the 1940s and the historical and pop-culture references contained in them. He has written for Animato!, APAtoons, and was the creator of The Warner Bros. Cartoon Companion.

E.O. Costello is a New York-based attorney, whose love of history has led him to study, in depth, the cartoons of the 1940s and the historical and pop-culture references contained in them. He has written for Animato!, APAtoons, and was the creator of The Warner Bros. Cartoon Companion.

Excellent, exhaustive work here, E.O.

For more on Selzer, you can read this short post from 2011: https://tralfaz.blogspot.com/2011/11/edward-selzer.html

I wonder if he was related to Richard Selzer, who worked as a go-fer on the Warner lot, and later became the fashion designer Mr. Blackwell?

No, to my knowledge we are not related. I have never heard nor seen the name Richard Selzer in our family.

No, we are not related.

Yes, we are Jewish.

Look for his birth record in Germany.

Best,

Eddie’s granddaughter.

Thanks for the new info on Eddie Selzer. I was interested in that “Inter-Office Communication” memo. I know Eddie Selzer didn’t get along with Clampett. Jones seemed to dislike him as well. Tashlin didn’t stay long and Friz walked out over Tweety being dumped from the “Tweetie Pie” Academy Award winner cartoon. Did Selzer and McKimson get along? Could it be that Selzer could see that moving McKimson up to the director position was his one good move?

In a 1971 interview, Robert McKimson told Michael Barrier how he became a director: “I felt that I could do the job as well as anyone else there, and I had the proper experience, so when Tash left, everybody and his brother was saying, ‘I’m going to take Tash’s place.’ So I went to Eddie Selzer and asked him if Tash was leaving. He said yes, and I said it was about time that I took it over. He said, ‘Fine, do you want it?’ I said sure, and he said, ‘Well, somebody told me you didn’t want it.’ I said, ‘Well, certainly.’ That was all there was to it, and I took it over.”

Other than admitting that, at times, Selzer could be a good audience, McKimson had nothing good to say about the man in that interview. He complained that Selzer refused to submit McKimson’s best cartoons (e.g., “The Hole Idea” and “Hillbilly Hare”) to the Academy for consideration; that he always assigned the best animators and layout men to Freleng and Jones, leaving McKimson with the dregs; that he didn’t like the Tasmanian Devil and refused to let McKimson make any more cartoons with that character until Jack Warner overruled him; that he always tried to get involved in story, but didn’t know the first thing about it. As McKimson put it: “It was such a square idea of humor that he had. We did pictures in spite of him, rather than because of him.”

There was mutual respect and healthy disagreements that fueled creativity but when all was said and done my grandfather/family was close friends w/many of the creative team and he made sure to acknowledge wins were because of them. Many of us were at Chuck’s memorial and very pleased to see one another.

This is a very interesting article. It’s nice, for a change, to see Eddie Selzer presented as a person with some depth, and to know that there were aspects of his life in which he was not only competent, but a true champion. But when it came to making cartoons, I’m afraid he was every bit the feckless boob that Jones, McKimson et al. made him out to be.

Excellent work, E.O. I will say I never cared for the damage done to cartoon history by Chuck Jones’s constant intemperate comments about Schlesinger and Selzer and management in general. His large talent to one side, Jones was definitely an artistic snob with an occasional nasty edge. I recall Pete Alvarado talking to me and mentioning that Selzer was a very nice man, and I know Freleng had occasional clashes about production but overall got on well with him. In fact I am just recalling Alvarado also complimented Selzer in a printed interview, I believe it was with Amid Amidi in the old “Animation Blast.” I ‘m not saying these bosses were perfect people, and no doubt their hard-nosed sensibilities were at odds with the creative artists at times, but Jones really did come across as snarky in painting his bosses as caricatured philistines and troglodytes. And so many people believed him that latter day historians like yourself must continue your good work in fleshing out the real person. (Possibly Quimby at MGM was even more hopeless regarding animation matters, yet even Bill Hanna spoke graciously of him to me.)