During the late 1930s, as Donald Duck became an increasingly popular cartoon character, the Disney studio developed a special corps of artists known as the “Duck Men” animators with a particular knack for capturing Donald’s distinctive waddling movements and belligerent personality. As the making of Donald Duck cartoons became an established Disney franchise in its own right, the “Duck Men” were kept busy animating Donald’s latest adventures. A later generation of Disney fans, learning of this colorful appellation, eagerly began to apply it to other important individuals in Donald’s life: comics legend Carl Barks, inspirational voice talents Clarence Nash and Tony Anselmo, directors Jack King and Jack Hannah. All have been identified in later years as “Duck Men,” and with good reason. In the meantime, however, some of the artists in that original specialized animation unit have been overlooked.

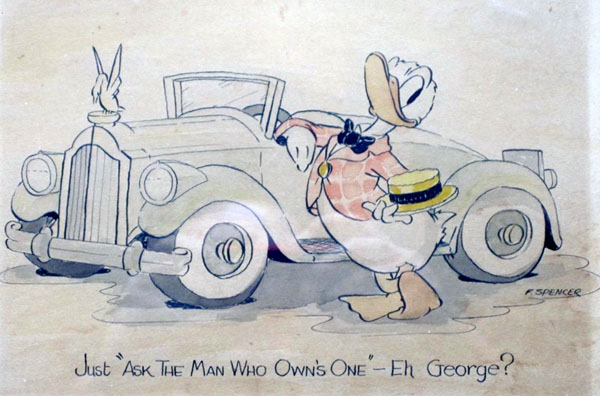

One of those original artists was Fred Spencer. Today Spencer’s name is not exactly unknown, but he rarely receives the recognition he deserves as a shaping force in Donald’s imaginary life. Not only did Spencer animate Donald’s comical walk and mercurial changes of mood with the best of them, he actually gave the Duck a makeover, radically altering his appearance and crafting the character as we know him today. What Fred Moore was to Mickey Mouse, what Norm Ferguson was to Pluto, what Art Babbitt was to Goofy, Fred Spencer was to Donald Duck.

One of those original artists was Fred Spencer. Today Spencer’s name is not exactly unknown, but he rarely receives the recognition he deserves as a shaping force in Donald’s imaginary life. Not only did Spencer animate Donald’s comical walk and mercurial changes of mood with the best of them, he actually gave the Duck a makeover, radically altering his appearance and crafting the character as we know him today. What Fred Moore was to Mickey Mouse, what Norm Ferguson was to Pluto, what Art Babbitt was to Goofy, Fred Spencer was to Donald Duck.

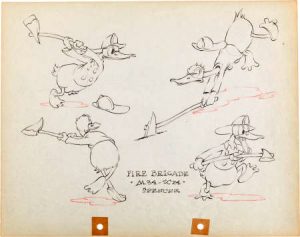

Spencer seems to have animated the little feathered troublemaker for the first time in late 1934–early 1935 for Mickey’s Service Station, the first of the Mickey-Donald-Goofy “trio” pictures. Mickey, Donald, and Goofy shared numerous group scenes in Service Station, and these were parceled out to a half-dozen animators. But it was Spencer who animated Donald’s solo actions: yanking at the car’s taillight, reducing its radiator to a pile of unraveled junk, and generally getting in the way and impeding progress. Spencer showed an immediate affinity for the character, and soon afterward he was assigned more Donald scenes. In the next “trio” picture, Mickey’s Fire Brigade, he animated the Duck’s axe-swinging pursuit of the little humanized flames. And in the all-star cartoon On Ice he contributed an extended performance: Donald’s mischievous practical joke on Pluto, his uproarious enjoyment of the dog’s discomfiture, and his sudden panic when a gust of wind swept him to the brink of a roaring waterfall.

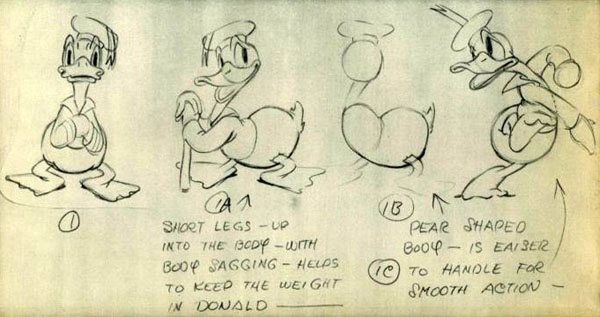

By the time On Ice was released in September 1935, Spencer was an experienced Duck animator and had taken the initiative to suggest some changes in the character. In the mid-1930s the Disney animation staff was rapidly expanding, and as more and more artists began to animate the major characters, the studio issued model sheets and analyses to help maintain consistency. Late in 1935, Fred Spencer created both the new model sheets and the analysis of Donald Duck. Rather than simply codifying the Duck’s original design—as pleasing as it was—Spencer effected a major redesign, creating a character that was more appealing to the eye. In effect, he gave us the Donald Duck we still recognize today. Some of his design changes were made for practical reasons. “The eyes are not round as in previous pictures,” he explained. “They are more oval in shape and are kept to the side of the head. In this way more black can be used in the eyes for the expressions.”

By the time On Ice was released in September 1935, Spencer was an experienced Duck animator and had taken the initiative to suggest some changes in the character. In the mid-1930s the Disney animation staff was rapidly expanding, and as more and more artists began to animate the major characters, the studio issued model sheets and analyses to help maintain consistency. Late in 1935, Fred Spencer created both the new model sheets and the analysis of Donald Duck. Rather than simply codifying the Duck’s original design—as pleasing as it was—Spencer effected a major redesign, creating a character that was more appealing to the eye. In effect, he gave us the Donald Duck we still recognize today. Some of his design changes were made for practical reasons. “The eyes are not round as in previous pictures,” he explained. “They are more oval in shape and are kept to the side of the head. In this way more black can be used in the eyes for the expressions.”

Spencer created this guide while animating his Donald scenes in Orphans’ Picnic, and took the opportunity to put his own ideas into practice. The other artists followed his lead, and 1936 became the year in which Donald evolved, on the screen, into his permanent design. Some artists caught on to the changes more quickly than others—we can see variant versions of Donald’s design in a single picture, Alpine Climbers—but by the end of 1936, the Duck had assumed the form that would characterize him for the rest of his career.

It’s worth noting that Spencer, as an animator, was not confined to a single specialty. He had joined the Disney staff in 1930 and, as a junior animator, had worked on numerous Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphony shorts. After his promotion to full animator, in addition to his Duck assignments, he animated extensive scenes in Mickey’s Parrot. When the studio tackled its first feature-length film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Spencer was part of the crew animating the dwarfs. His contributions here included, among other things, the key scenes of Dopey with the soap in the washing sequence, and several dwarfs’ performances on their homemade instruments, and Sneezy’s climactic sneeze, in “The Silly Song.” All in all, however, Spencer’s place in Disney history unquestionably rests on his work with Donald Duck.

Why is Fred Spencer relatively little remembered today? Almost certainly because his life and career came to a tragically premature end in 1938. I am indebted to historian Joe Campana for the details: on Friday, 11 November 1938, after attending an Armistice Day football game, Spencer was driving home with friends when he was killed in an auto accident. Had he lived, we can only speculate on further contributions he might have made to animation history. His work with Donald Duck would likely have continued, but he may also have branched out into other specialties. In any case, he would surely be more widely celebrated today.

Why is Fred Spencer relatively little remembered today? Almost certainly because his life and career came to a tragically premature end in 1938. I am indebted to historian Joe Campana for the details: on Friday, 11 November 1938, after attending an Armistice Day football game, Spencer was driving home with friends when he was killed in an auto accident. Had he lived, we can only speculate on further contributions he might have made to animation history. His work with Donald Duck would likely have continued, but he may also have branched out into other specialties. In any case, he would surely be more widely celebrated today.

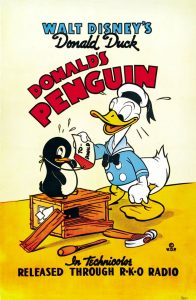

Even as it is, Spencer left a remarkable legacy. And, as if to secure his place in history, he left us with one last opus before departing this life: a final virtuoso performance of Duck animation. Donald’s Penguin was released in August 1939, but production was actually complete by the autumn of 1938 — and both the draft and the exposure sheets confirm that Spencer animated more than half the footage of this picture singlehanded. The first uneasy exchanges between Donald and the title character, the penguin’s cunning waddling action and Donald’s imitation of it, the penguin’s discovery of, and predatory interest in, Donald’s goldfish, Donald’s belated realization that the tank’s goldfish population is decreasing—all of this is Spencer’s work. So is the entire closing sequence: Donald cornering the penguin with a shotgun, his grim determination, his gradual change of heart, and the surprising ending. In between these two bravura sequences are several passages by other “Duck men:” Johnny Cannon, Lee Morehouse, Paul Allen, and Don Towsley. All of them, to be sure, were undeniable talents in their own right. But if any further proof were needed of Fred Spencer’s importance as a Donald Duck animator—his technical mastery of the medium, and his feeling for nuances of the character’s personality — Donald’s Penguin provides an eloquent final statement.

Next Month: The Unlucky Duck

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

That’s an excellent profile of Fred Spencer; nice of you to give credit where it’s due. Spencer also drew a short-lived Mickey Mouse comic strip for the DeMolay international newsletter. He and Walt were both DeMolay boys, as well as fellow Missourians.

Since you are an authority on all things Duck, I hope that you can resolve a dispute of long standing. My family used to watch The Mouse Factory in the early ’70s, and I remember that every episode ended with the same scene. First we’d see a whirring, buzzing mass of clockwork and gears. Then Donald Duck, dressed as a caveman for some reason, came out and looked at the gizmo for a moment. Then he turned to the camera and said something, and a moment later he turned back and said something else. I thought he said “What does it do?” and “I thought not!” My sister thought he said “What fancy tools!” and “After all that work!” We used to argue about it every week.

What did Donald say at the end of The Mouse Factory? And why was he dressed as a caveman? If you can unravel these riddles, you will have truly earned the title of “Duck Man”.

I know why he was dressed as a caveman. The scene was taken directly from “Donald and the Wheel”, a 1961 featurette in which Donald portrays the supposed inventor of the wheel. The lines for the “Mouse Factory” were overdubbed from the original scene. In the original, he says something like (not that I’m an expert–who really can interpret duckspeak?) “What’s it to do?” and a moment later “But what’s it for?”.The context of the scene is that he is being shown a set of wheels and gears which are purely a demonstration with no practical purpose. For the “Mouse Factory” redub, I believe the revised lines are “What a to-do!” (meaning what a commotion or what a racket) and “It won’t work!” These are purely my guesses as to what our duck friend is saying in both versions. But at least I could solve the caveman part of the mystery. Find “Donald and the Wheel” and watch it, and that closing of “The Mouse Factory” will make more sense.

I’m sorry to forfeit the title of “Duck man,” but I can’t improve on Frederick’s reply! Thank you both!

I believe Donald in THE MOUSE FACTORY asks “What does it do?” and then comments “It won’t work!”

Well, at least that answers one question definitively. Thank you!

Thanks, David, I’m sure that’s correct. You guys are true Duck Men!

Thanks so much for your always illuminating articles! You mentioned that there was a year’s delay between the end of production on “Donald’s Penquin” and its release in 1939. I was curious if you had any information about why this delay occurred. The similarly themed book “Mr. Popper’s Penquin” came out in 1938. I was wondering if Disney delayed the cartoon so as not to appear to be copying what was then a very popular children’s book.

Thank you, Michael. That’s an interesting point about “Mr. Popper’s Penguin,” and I wouldn’t rule it out as a reason for the cartoon’s delayed release. It’s also the case that the studio had such a backlog of completed shorts by that time that a number of others were similarly delayed. Both “The Practical Pig” and “The Ugly Duckling” were completed, and even shown theatrically, in 1938 — but, like “Donald’s Penguin,” they didn’t get a general release until 1939, and today are always thought of as 1939 films.

Penguins have always been popular. They’re not a flash-in-the-pan, flavour-of-the-month type of animal (hear that, sloths?). Disney had the Silly Symphony “Peculiar Penguins” in 1934, Fleischer the Color Classic “Peeping Penguins in 1937. Bugs Bunny teamed up with a penguin in “Frigid Hare” and “8 Ball Bunny” (1949 and 1950 respectively), and Chilly Willy debuted shortly thereafter. “March of the Penguins” and “Happy Feet” were in cinemas simultaneously in 2006. The idea that Walt would have held back the release of “Donald’s Penguin” out of fear that the media environment was becoming super-saturated with penguin stories, is highly doubtful.

On the other hand, the animation of the penguin in the climactic scene is markedly similar to that of the cowering baby bunny rabbit in “Little Hiawatha” (1937). But there doesn’t appear to have been any overlap in animation or story staff between the two cartoons.

Mr.Popper’s Penguins with Jim Carrey & Carla Gugino was a big hit a few years back, so was Tennessee Tuxedo of the 1960s!

I expect you’re acquainted with Stephen Jay Gould’s 1977 essay “A Biological Homage to Mickey Mouse”. Gould, a professor at Harvard, wrote a monthly column on evolutionary biology for Natural History magazine until his untimely death in 2002. The essay was reprinted in the collection THE PANDA’S THUMB (W. W. Norton, 1980) and also in THE MICKEY MOUSE READER, edited by Garry Apgar (University Press of Mississippi, 2014).

Gould maintains that the changing design of Mickey Mouse over the years reflects an evolutionary phenomenon called neoteny, in which juvenile traits of ancestral forms are retained as adult features. Making Mickey appear younger has the effect of making him more appealing: “When we see a living creature with babyish features, we feel an automatic surge of disarming tenderness. The adaptive value of this response can scarcely be questioned, for we must nurture our babies.” Thus the development of his design paralleled that of his character, becoming less mischievous and ribald as time went on.

As for the subject of this post, Gould wrote: “Donald Duck also adopts more juvenile features through time. His elongated beak recedes and his eyes enlarge; he converges on Huey, Louie and Dewey as surely as Mickey approaches Morty. But Donald, having inherited the mantle of Mickey’s original misbehavior, remains more adult in form with his projecting beak and more sloping forehead.”

It is unfortunate that Gould speaks only of “the Disney artists” in the abstract, and does not acknowledge specific artists like Fred Spencer. It seems incredible today that someone could write an essay on the evolution of Mickey’s design without so much as a mention of Fred Moore. But I think this just reflects the paucity of good books on animation history at that time. Gould’s only source of information on Disney is Christopher Finch’s THE ART OF WALT DISNEY (1975); all his other citations are scientific treatises. Therefore your writing on Spencer’s analysis and model sheets is important in establishing the record. Whether Spencer consciously sought to make Donald appear younger, I don’t know; but his specific design changes were definitely in that direction

I love that Christopher Finch book and it was what inspired me to find out more about the work of the various Disney artists. 🙂

It’s interesting, the idea that “the Disney artists” made their characters appear younger and more childlike over time. Chuck Jones seems to have been doing the opposite over at Warners. His designs for the characters aged with him.

Not including animator credits in short cartoons until the 1940s probably made that difficult.

Maybe a Tashen Donald Duck book is planned?

Always found this a disturbing cartoon.

This a great article! Finally, I have read something that really gives credit to Fred Spencer as an artist and his contributions to Disney. We grew up with Donald in our household. My great-grandfather was a life-ling friend of Fred’s, they attended school together and remained close afterward. Fred visited my great-grandfather in Kansas City, MO just before his untimely car wreck. The newspaper in Kansas City printed an article of one of his last illustrations, sent to my infant grandmother, Sandra Fries, as a birthday gift. It was received by grandma within days of Fred’s death, an eerie coincidence. This story has always fascinated me and today I am very grateful to learn a larger piece of the puzzle. Cheers!

Fred Spencer was my grandfather, Richard Latham’s cousin. I was so happy to read this with my kids. It’s amazing to learn more about the history of my family. Thank you!