In 1956 the company Associated Artists Productions (AAP) purchased the library of Warner Brothers Merrie Melodies cartoons produced to 1948 and Looney Tunes cartoons made between 1943 to 1948–a total of 337 short films. AAP immediately offered the cartoons for television syndication, and in 1957 they made their debut on local stations nationwide. African and African American characters appear in eleven of the 337 films as the main characters (not counting the Inki series), depicted largely as nearly-naked African natives, antebellum southern slaves, and northern jazz-lovers.

African Americans protested the theatrical circulation of some of these cartoons upon their original releases, and television networks refused to show similar cartoons from other studios. However, syndicated television depended on the standards of individual stations instead of one national network, and many stations had no qualms about airing the eleven cartoons.

African Americans protested the theatrical circulation of some of these cartoons upon their original releases, and television networks refused to show similar cartoons from other studios. However, syndicated television depended on the standards of individual stations instead of one national network, and many stations had no qualms about airing the eleven cartoons.

The motion picture studio United Artists (UA) acquired AAP in 1957 and kept all 337 cartoons in syndication. UA kept the cartoons after the Transamerica Corporation purchased the studio in 1967. The following year, Transamerica combined UAs separate television production and television distribution units, and UA withdrew the aforementioned eleven cartoons from circulation. The removal was part of a wave of programming changes in television in 1968–the year of the federal governments declaration that the United States was becoming two societies, black and white, separate and unequal and the year of civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr.s assassination. Scripted television programs added African American supporting characters, and one new show (the sitcom Julia) starred an African American woman in a leading role as a nurse instead of a domestic servant.

On a monthly basis, I will examine each of the withdrawn Warner Brothers cartoons–collectively known as the “Censored 11” — and discuss the content that likely led UA to pull the films from syndication.

Collectively speaking, the Censored 11 outlived the times, highlighting outdated characterizations that culturally reinforced segregation in a new era of federally mandated integration. I intend to distinguish each films timeless aspects from its ethnically dated aspects.

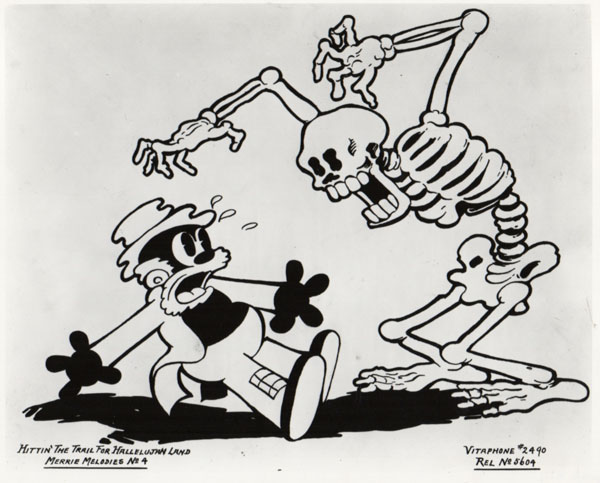

First on the list is Hittin the Trail for Hallelujah Land–a Merrie Melodies episode from 1931. It is the only cartoon from the Harman-Ising Studio among the Censored 11 and the oldest cartoon on the list. This film gives a hint of how Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising diverge in caricaturing African Americans. Harman worked with jazz scores and fashioned his Looney Tunes star Bosko as a blackface crooner of contemporary music; later at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), he directed cartoons featuring caricatures of African American jazz artists. Ising, in contrast, handled cartoons

set in the antebellum South. Hittin is the first, but later at MGM he directed The Old Plantation.

But back to Hittin, it is very understated in its depiction of the antebellum South. No one specifically mentions slavery, and no dialogue or scenes refer to a southern location. The river and the riverboat are not identified as the Mississippi River and a Mississippi showboat.

In terms of character design, the pigs Piggy and Fluffy, the wagon driver, and the singers opening the film all have jet-black skin.

Sound, by and large, sets up the antebellum setting. Fluffy and the singing ghosts in the graveyard refer to the driver as Uncle Tom, and the drivers namesake is a fictional slave of Harriet Beecher Stowes antebellum novel Uncle Toms Cabin.

Throughout the book Uncle Tom lives in slavery in the South. Thus, any reference to Uncle Tom in cartoons is a reference to a slave. So it is with Hittin, but Uncle Tom demonstrates his service by driving Fluffy in the wagon. The minstrel song Camptown Ladies not only musically shapes the setting but contributes to Uncle Toms ethnic depiction when he alone sings the song. Sound also constructs his ethnicity when he says, Holy mackerel–a catchphrase from fictional African American character Andy Brown of the contemporary radio sitcom Amos n Andy.

Visually, Uncle Tom and the opening singers resemble African American caricatures of the era. Although Piggy and Fluffy have jet-black skin, their white snouts define them as pigs and, therefore, not African American slaves. The fine clothing of the pigs identify them as free, in contrast to the ragged clothing of Uncle

Tom and the singers. In addition, the ethnic stereotype of fear of ghosts in a graveyard comprises part of Uncle Toms ethnicity, and Ising made ample use of Uncle Toms bugged eyes for that scene.

Civil rights groups had not yet organized campaigns against cartoons in 1931, and I have not found evidence that they tried to get Hittin out of theatres. However, movie studios had long abandoned the practice of portraying slaves as happy, singing laborers by 1968.

Hittin definitely contains this gross caricature of the peculiar institution, and likely for that reason UA included it in the Censored 11.

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

For the most part, it is indeed correct that all of the censored 11 have been kept from even syndicated TV. I was made aware of most of these titles through various curiosity animation festivals that devoted at least one night to these cartoons so people were aware of them.

Warner Brothers was mostly very careful that the films were not seen on TV in heavy rotation; even the now public domain titles–and those who read this weblog know which ones those are–were not seen anywhere except for those who issued splicey prints of same on VHS when home video became a way of enjoying one’s favorites or curiosities in binge-watching in homes all across America and elsewhere. Yet, as some also know, the banned cartoons grew in number as the years progressed, and we can find titles that were not censored from syndicated packages when older generations were younger and classic LOONEY TUNES and MERRIE MELODIES, both black and white and full color, were played for our amusement on many a weekday afternoon or morning or weekend, as alternative to major network cartoon fare.

As you can see, what holds this together in some ways is the musical score, playing the title song over and over again, interspersed with other such tunes that define the parody of those times. Looking back, I find it strange that there were so many parodies of those times. After all, weren’t many of us glad that such atrocities were abolished? The jazzy scores make them worth collecting and inserting in collections as a smaller part of the larger whole time capsule, and I’m glad we’re getting a detailed peek at them in their proper context here.

Some of the Censored 11 were still being aired on stations in the South in the early 1980s — if a station had owned syndication rights to the AAP Warner Bros. cartoons prior to 1969, UA didn’t ask them to send the now-banned cartoons back. They just didn’t sent out new prints of those to stations either just buying the pre-48 WB cartoon package or who needed a replacement for a damaged print.

It wasn’t until video copies of the pre-48 package started replacing film prints in he 1980s that the Censored 11 finally fully disappeared from TV (in contrast, some stations, like WNEW in New York, pulled not only the Censored 11 well before 1969, they also balked at airing many of the most overt World War II-themed cartoons as well)>

Some of the Censored 11 were still being aired on stations in the South in the early 1980s

I’ve heard this and wondered if it’s true, or there is any hard evidence of it beyond the purely anecdotal. (I’ve similarly heard that there were supposedly TV stations in the South that continued to air reruns of The Amos ‘n’ Andy Show for years after CBS officially withdrew it from syndication.)

For one thing, if United Artists was going to go to the trouble to withdraw these eleven titles from the package, and if they were that concerned about the offensiveness of the films’ content, I find it difficult to believe they’d be that casual about not expecting stations to return prints of them.

For another, I grew up in the South and have relatives spread through a wide swath of that region. We traveled a lot, and as a Warner Bros. cartoon junkie seeing these films on stations in several Southern states throughout the ’70s, I can assure you that I never saw a single one of those eleven cartoons on any TV station anywhere in this part of the country.

So, video killed the Censored 11. Thanks for the info!

Unless you have a VHS or Beta recording, I think any evidence will inevitably be anecdotal. Cartoons as extreme as Bugs Bunny Nips the Nips and Half-Pint Pygmy were still being offered through 16mm to stations as late as 1983, so it’s not much of a stretch to assume stations still had old prints of the Censored 11 and still ran them.

I personally saw “Jungle Jitters” air on KTVT in Dallas-Fort Worth one mid-afternoon around 1983, before the station became a CBS affiliate, and was airing kids’ stuff in the late afternoon time slots. (Even Ted Turner’s WTBS would air the uncut version of “Fresh Hare” all the way to 1986, before the new video copies of the cartoon TBS got after Turner acquired the MGM-UA library removed the closing minstrel scene.)

If you did it was a fluke occurrence. I live in Dallas and spent many, many hours of my life watching cartoons on KTVT, and I have absolutely no memory of ever seeing any of the censored eleven there, certainly not from the early ’70s on. Hell, even their print of SEPTEMBER IN THE RAIN was edited to remove the blackface footage. Nor do I remember them ever running questionable cartoons that remained in circulation like CONFEDERATE HONEY. They were conscientious enough not to run Popeye cartoons like POP-PIE A LA MODE, THE ISLAND FLING and POPEYE’S PAPPY, and to edit the A LA MODE footage from SPINACH VS. HAMBURGERS. I’m not saying that someone couldn’t have slipped up and put a print of one of the censored eleven on the air, but if it happened it was certainly not something they typically did.

Didn’t look like a bootleg print, although by the early 80s, most film prints local TV stations had been using for 20 years or more were starting to look a little ragged. But it did air, and I was shocked to see it, because it was my first time to view that cartoon (it’s also possible KTVT might have pulled some of the “Censored 11” shorts by the early 1980s, but not this one).

Too bad I didn’t have my VCR going when “Jungle Jitters” aired, just to document it did show up — I did have the thing going a few years later when TBS ran the unedited “Hare Force” just prior to getting the version on video with the edited ending.

(Correction on that last post — “Fresh Hare” and not “Hare Force” was the cartoon with the censored ending.)

Well, you saw what you saw, but as a Dallas-ite who spent way too much time parked in front of cartoons, I have to agree with Barry that the airing you saw of JUNGLE JITTERS was a fluke. KTVT, by that point, just didn’t ordinarily show cartoons featuring those kinds of ethnic stereotypes. Now Native Americans stereotypes they had no problem with at all. They were just very careful about African American stereotypes.

Mistakes get made, though. One afternoon they aired two black and white Popeye cartoons during their ordinarily all-color Popeye show. I called the station to thank them and encourage them to continue the practice, but they told me it had been a mistake and the wrong reels had been pulled. So no more black and white Popeye.

Nobody seems to have been able to figure out what to do with the minstrel show ending to FRESH HARE that would be ideal. I’ve seen it so that it ends very abruptly with Bugs saying, “I wish . . . I wish.” I’ve also seen them take that little hopping dance Bugs does when he first starts singing “Dixie,” before the transition to the minstrel show, and loop that repeatedly to the fadeout, even though it doesn’t match the soundtrack once Elmer and his men turn into a blackfaced chorus.

I suppose someone at KTVT could have known the print was there and just decided to run in through the telecine to be ‘edgyy’, but apparently they did get away with it.

(And running cartoons that were off-limits by the 1970s could happen elsewhere — no station was more careful about what cartoons they did and didn’t air out of the WB syndication package than WNEW in New York, going all the way back to the early 1960s. But every once in a while someone at Ch. 5 would sneak “Which is Which?” from the post-1948 package onto the air. That one I can remember seeing twice on WNEW in the 1970s, once before 7 a.m., but also once in the mid-afternoon, when it was more likely more people would be watching and someone might see that Bugs effort and call the station to protest).

I’m a bit late, but wanted to chime in here. Never saw any censored 11 cartoons growing up in Detroit in the ’80s, but definitely saw BBNTN one morning in 1985 or 1986 on WKBD. The same station also aired Fresh Hair uncut (and later in a clumsily edited version), and would do things like air B&W Popeyes in the middle of the Bugs Bunny and Friends show without warning. By around 1990 these homegrown package shows were discontinued – although they seemed to last longer in the Detroit market than elsewhere, and WKBD never seemed to have received the Turner upgrade in the mid-’80s.

I wonder why they felt the need to use these black stereotypes as characters in this toon. It’s just a generic plot that would be the same with any mouse, dog,cat or pig character.

In those days, UNCLE TOM’S CABIN was universally known, both from the novel’s ubiquity, and perhaps even more so from the profusion of stage-play adaptations. The same reason that so many cartoons are based on nursery-rhyme characters and scenarios.

This essay series could easily extend past the so-called “Censored 11”, as there are apparently dozens more that are removed from circulation. For example, “Bugs Bunny Nips the Nips”, “Tokio Jokio”, etc.

It’s important sometimes to understand the historical context of such films to fully understand their cultural context and the significance of such infamy to modern audiences. And with more people revisiting them (the last post/videos about them I’ve seen came from Channel Awesome’s The Rap Critic), it is important for expert eyes to view these films to provide an educated guidance to them so that we can assess ourselves on what they were doing and why we see them with modern eyes as such controversial matter.

I’ll look forward to other posts in this series for such ‘historical’ guidance and context into why they are The Censored Eleven in Warner Brothers’ back catalogue.

Great idea for a series, Christopher. Thanks!

Does anyone know why the original 1956 AAP acquisition did not include Looney Tunes from 1931-1943?

I did see them as a kid in the 50s-60s, in separate non-AAP TV broadcasts. They had the “Sunset Films” branding spliced onto the titles. Maybe Sunset got to Warner before AAP?

You ask about the “original 1956 AAP acquisition” which did not include Looney Tunes (from 1930-1943). That’s because Warner Bros. sub-licensed them to a TV subsidiary, Sunset Productions, a year or two earlier – and they were already in syndication.

What’s odd is that Warner’s withheld the b/w Harman-Ising Merrie Melodies (1931-1933) from the Sunset package.

Time has a funny way of changing these films. I wonder how many small children of different races TODAY would even catch what was considered so offensive in these. Most of the characters in this film come off as Mickey Mouse knock-offs. Also the Uncle Tom character is little different than many Caucasian “rural” types who spit tobacco and also work with mules. At least he is not presented as stupid here, if predictably sacred of spooks. As animation techniques got more Disneyesque and human characters more human-like, that is when you start running into much more offensive stereotypes.

Side note here… 1968 was definitely a year so many changes needed to be made. That summer, CBS aired a series “Of Black America” (which can be seen on YouTube) and Bill Cosby criticizing all of the black stereotypes in old Hollywood movies certainly was taken seriously at that time. This resulted in a mass “clean up” on TV than included these cartoons. In the 1969 Best Picture winner that was filmed in ’68, MIDNIGHT COWBOY, we see UA-owned material from the Warner vaults (since the movie was made by UA) shown on a TV screen including shots of Bette Davis and, most amusingly, Al Jolson in blackface.

Apparently director John Schlesinger was making a statement about how scattered TV programming had become, taste-wise. Later we see Joe Buck (Jon Voigt) watching a talk show with a poor dog being forced to wear clothes and false eyelashes, suggesting something just as bad as blackface. This was a period when there was great sensitivity regarding what should and should not be broadcast. Cartoon violence and western gun play were also in decline after so much Vietnam war footage and two recent assassinations had invaded family living rooms “in living color”.

Most TV stations got rid of their “film chains” (16mm telecine machines) in the ’80s, when syndicators distributed films to stations on tape (later still, on satellite feeds).

A non-animated example: In the late ’60s, King World edited most of the racial gags from the Little Rascals shorts, to keep them on the air (back then, they were the only program KW offered). But there was at least one station (WRBL, Columbus, Georgia) that continued to run the uncensored Monogram/Interstate prints of the Little Rascals till the late ’70s or early ’80s.

Having watched this cartoon for the first time, I think this cartoon *could have* run on television in an edited form. Most of Uncle Tom’s presence could have been edited without affecting the cartoon much (i.e. removing his dropping off Piggy’s girlfriend at the boat, removing Piggy rescuing him from the ocean). Some of the skeleton parts could have been kept, just enlarge the screen to eliminate Uncle Tom from some shots.

The short I think would be down to 5 minutes, I think it could have been possible.

As mentioned above, it seems strange that Harmon & Ising felt the need for a black slave character for this cartoon. Heck it could have just been Piggy himself lost in a cemetery and being pursued by singing skeletons the whole cartoon. Blown opportunity.

It’s quite a generic plot, but I guess interest in Uncle Tom’s Cabin just popped into too many heads then.

I’m glad this series has begun and I look forward to the subsequent entries. These shorts can never be normalized, but discussing them (and yes, watching them in controlled conditions) is the only way to understand them.

Looking ahead, after the 11 have been discussed, is there the possibility for an ‘epilogue’ of sorts to discuss shorts that might not have been part of the ‘Censored 11’ but were still eventually weeded out of circulation (such as ‘Goin’ to Heaven on a Mule’ or ‘The Early Worm Gets the Bird’)?

I’d consider doing that, but of course it’s up to the webmaster.

Chris, we would all be grateful if you would continue this series beyond the initial “Censored 11”. We shall discuss!

What’s wrong with “The Early Worm Gets the Bird”?

Going to Heaven on a Mule was never part of the AAP package, only the Harmon-Ising era B&W Merrie Melodies were. If it had been, we would probably be talking about the ‘censored 12’.

So much of the changing context around these cartoons (and all such filmic stereotypes) has to do with the “we” who are watching them. They were always offensive, and it all depended on who was judging the depictions.

White audiences would not have found them offensive, and have/can always find someone African American to say they are not offensive and thus “prove” that the images are benign. People of color have always found them offensive, by and large, and it’s only recently that our voices are privileged enough to be heard in mainstream commentary, e.g., the news, online forums, social media, etc.

I find it difficult to stomach the refrain of “Oh, these didn’t used to be offensive, it’s censorship!” (This is what I’ve come to call the “nostalgic white critic view.”) When we hear or read this view, we should be asking “from whose perspective? To whom was it offensive, even back in the day? What was the impact of these depictions even when released, in addition to their effect on young and old minds today?” I’m appreciative that that old refrain isn’t being sung here. 🙂

In all the palaver abut the racism (real and supposed) in this cartoon, nobody’s talked about the musical aspect of it–what was supposed to make this “melodie” so “merrie”.

Most of the early Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies were built around songs that Warners’ music publishers had and were pushing.

In many cases, these ere songs that are known to collectors of records of the period.

But there were some that the record companies skipped entirely–and this was one of them. (Others include “It’s Got Me Again”, “The Shanty Where Santy Claus Lives” and “I’m One Step Ahead Of My Shadow”.)

The orchestral backing, credited, as usual, to Frank Marsales, is closer, at times, to the hotcha accompaniments to such shots as “Smile, Darn Ya, Smile” or “One More Time”, than to some of Marsales’ other scores, which sound more like salon music. There is some good hot trumpet, possibly from a preset or former member of Gus Arnheim’s band.

Likely as not, these were some of the best cats that Local 47 of the AFM could provide.

Likewise, the singers and voice actors are difficult, if not impossible,, to identify.

I remember seeing a looney tune on cartoon network as recently as 2006 or 2007 that had a blackface gag in it. Have they ever considered updating this list?

“In terms of character design, the pigs Piggy and Fluffy, the wagon driver, and the singers opening the film all have jet-black skin.”

Similar to Mickey and Minnie Mouse’s character design and jet-black skin in 1931? Piggy and Fluffy are even drawn wearing nearly-identical Mickey and Minnie clothes!

One thing I’ve always wondered, iIf the Censored 11 focused on shorts with African American stereotypes, why were the Inki shorts and other shorts like The Early Worm Gets The Bird considered acceptable?

I was going through a friends beta collection of pre-1948 WB cartoons that he taped in the late 80’s on our local KQCA Sacramento station a few years ago. I was surprised when I found Jungle Jitters on one of the tapes. The print quality was decent for that time. Unless this was also a fluke, maybe some local stations still ran them.

VERY Controversial take but there’s very little in this cartoon that’s racist. If you were to dub the cartoon and call him “Uncle Billy” or whatever, Nobody would think this is a stereotype.

Also there are worse cartoons that are more offensive than this.