Throughout the 1930s and into the 1960s, there were a handful of films produced by the iconic Jam Handy Organization that utilized elaborate stop motion animation sequences. The Jam Handy Organization, who produced a wide array of corporate and industrial motion pictures, frequently used animation of all kinds (technical, cartoon, and stop motion) as a way to further enrich their films’ content. The man who was responsible for the vast majority of the studio’s stop motion work was a notable filmmaker named Francis Lyle Goldman, aka Frank Goldman, whose work in the field of stop motion is just as noteworthy as other American stop-motion artists such as Ray Harryhausen, George Pal, and Arthur Clokey.

Frank Goldman began working for Jam Handy in the Autumn of 1935, however his filmmaking career and interest in stop motion date long before joining the organization. Originally an architect with a bachelors degree in science, Goldman began his filmmaking career as a technical animation director for the Bray studios in 1918. As indicated by Part 12 of Arthur Edwin Crow’s “Motion Pictures – Not for Theatres” published by Educational Screen, Goldman’s decision to drop his architect career and pursue filmmaking came after viewing a stop motion training film that was made by his cousin and Bray animator, J. F. Leventhal.Following Goldman’s departure from Bray in the early 1920s, he formed a partnership with Arthur Carpenter and established Carpenter-Goldman Laboratories Inc. Here he oversaw the production of several hand drawn animation films and stop motion films. Amongst one of these stop motion films (as documented in the 1950 Vol.11 No.3 issue of Business Screen Magazine) was a 1924 film for A.T.&T. in which a telephone assembled itself through stop motion; a film that Goldman would remake in the 1930s and also in the 1940s. In 1929 Goldman, who had acquired Carpenter-Goldman Laboratories Inc. from Arthur Carpenter several years earlier, sold his company and studio to Audio Cinema Inc. (a division of A.T.&T.) and became a Production Supervisor for the company acting as a producer, director, and a stop motion animator.

During these years at Audio-Cinema, which lasted until 1935, Goldman oversaw the production of several sponsored animated cartoons (i.e. “Once Upon A Time “(1934), Kool Penguins (1935), “Reddy Kilowatt’s What’s Watt” (1935)) and a number of stop motion films; unfortunately with the exception of Audio-Cinema’s “Paul Terry~Toon” cartoons no complete filmography of Audio Cinema’s/Productions’ animation output currently exists. Fortunately two Audio films that beautifully demonstrate Goldman’s filmmaking and stop motion skills do exist as of 2016, one of which is his best efforts: the iconic 1933 industrial film “The Rhapsody In Steel”.

A scene from “The Rhapsody of Steel” of the Ford V8 man orchestrating the assembly of a Ford Motor Car in stop motion.

The first half of the twenty-two minute film which was shot on location by cinematographer Leo Lipp under the direction of Goldman, shows how Ford factory men build a Ford Sudan at Ford’s plant. The second half of the film, shot at Audio’s New York stages, is an animated cartoon sequence which combines stop motion animation with hand drawn cartoon animation and imaginatively shows the Ford V8 logo coming to life and conducting stop motion Ford parts to construct an automobile. The film is one of Goldman’s best productions for Audio and is also extremely reminisce of other films that he would later make for the Jam Handy Organization.

A scene from Frank Goldman’s 1932/33 cartoon and stop motion A.T.&T. film “Getting Together”. This film, a sound remake of Goldman’s 1924 A.T.&T. stop motion film, would be remade again at Jam Handy by Goldman in 1947 as “Just Imagine”. Image courtesy of Thomas Stathes.

Frank Goldman resigned from Audio-Cinema (now Audio Productions) and became an employee of the Jam Handy Organization in the Autumn of 1935. It’s not known why he left, however his departing may have just been a result of fellow Bray alumni Mr. Jamison Handy offering him better career ventures. (Goldman’s constant trips to Detroit while overseeing production of “The Rhapsody in Steel” may have helped reconnect this relationship). His arrival at Handy’s came around the same time period that many talented folks, several from Hollywood (such as cinematographer Gordon Avil), became members of the Jam Handy Organization thus causing a dramatic improvement in the quality of the studio’s films; an increase that Goldman certainly contributed to with his filmmaking, animation and special effects talents.

Interestingly shortly following his arrival, Jam Handy made two Chevrolet ‘Direct Mass Selling’ films that were Chevrolet re-adaptions of Goldman’s “Rhapsody of Steel”: 1936’s documentary two-reeler “The Master Hands” (a re-adaption of the first ten minutes of ‘’Rhapsody’) and the 1936/37 one-reeler Technicolor cartoon “A Coach For Cinderella” (a re-adaption of the second half of ‘Rhapsody’). Many other films that were made from 1936 and into the 1950s, most specifically those made for the Chevrolet Direct Mass Selling program that was in use from 1935-1942, featured intriguing visual effects that were executed by Goldman.

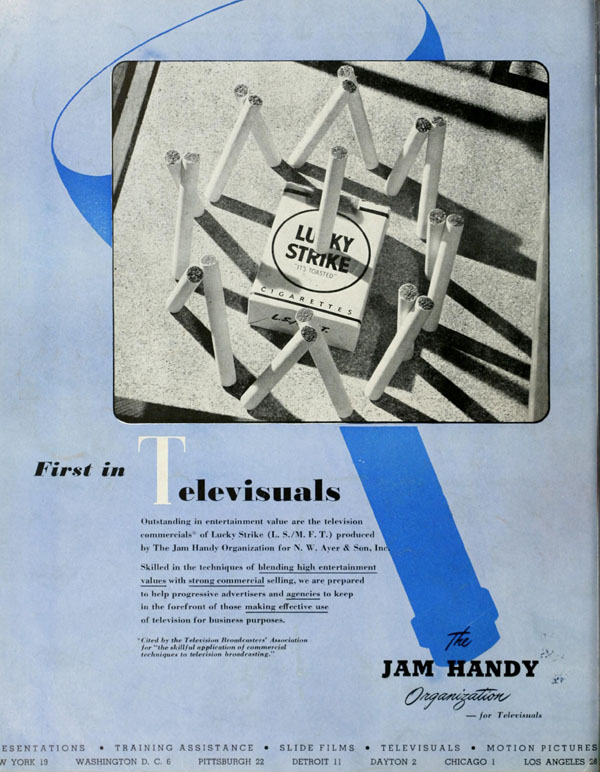

In addition, Goldman also contributed his talents as a stop motion animator to the Jam Handy Organization and was responsible for several stop motion cartoons (i.e. 1939’s “Round & Round”), stop motion television commercials (i.e. 1949’s Lucky Strike commercials), large scale stop motion sequences for live action films (i.e. 1937’s “Precisely So”), and even brief stop motion sequences that appeared in hundreds of Jam Handy productions. Along with producing these various films and sequences, Goldman also gave lectures at universities and at film technology events in which he promoted the history and benefits of stop-motion in educational films. These lectures were both independently done and also presented on behalf of the Jam Handy Organization.

One of Jam Handy’s “First in Televisuals” trade ads, this one promoting one of Frank Goldman’s Lucky Strike cigarette commercials. The Jam Handy Organization is credited by many trade magazines and journals of era to creating the first commercial films made specifically for television.

In terms of the number of stop motion films and sequences that Goldman worked on at the Jam Handy Organization is a bit of a mystery, as unfortunately no filmography or official documentation of his work currently exists. Interestingly once Goldman left Audio Productions (where trade magazines would publicize some of his stop motion projects), mention or brief notes of his stop motion work for Jam Handy was hardly mentioned at all by trades. Despite no documentation existing, one can identify Goldman’s particular stop motion style in the Jam Handy films, which is identical to his Audio Cinema/Productions work. Below is a listing of several existing films that feature Frank Goldman’s stop motion which have been rescued, and made available to the general public by archivist Rick Prelinger:

ONE REEL STOP MOTION CARTOONS

Round & Round & Round & Round (1939)

Round & Round & Round & Round (1939)

Sponsor: General Motors Public Relations Department

Theatrical and Non-theatrical Distribution: Jam Handy Organization and General Motors Public Relations Department

JHO Completion Date: March 9, 1939

Copyright Date: April 15, 1939

Original Number of prints (as indicated by copyright records): 66

Description: An educational one-reeler for elementary aged children demonstrating the concept of American free-enterprise. The film utilizes wooden toys designed and animated by Goldman, all set to a music box-ish xylophone score by Jam Handy musical director Samuel Benavie and narration by notable commentator Lowell Thomas. The film was exhibited in schools by local General Motors merchants where it was shown in gymnasiums or auditoriums; in school facilities that were without a projection booth, projection would have been made possible by a 35mm ‘suit case’ projectionist sent out by JHO. In addition, the film would have also been showed in movie theaters at kids shows sponsored by a local General Motors merchant as well.

Just Imagine! (1947)

Just Imagine! (1947)

Sponsor: A.T.&T.

Theatrical Distribution: Jam Handy Organization and Monogram Pictures

Non-theatrical Distribution: Jam Handy Organization

JHO Completion Date: September 9, 1947

Copyright Date: No Copyright Records

Description: A remake of Frank Goldman’s earlier A.T.&T. films (the 1924 Carpenter-Goldman Laboratories Bell Telephone film and his later 1932/33 Audio-Cinema film “Getting Together”). Just Imagine! features an animated Tommy Telephone demonstrating to a live action A.T.&T. representative how a bell telephone is assembled from 433 different parts through stop motion, all set to a classical music inspired score by Samuel Benavie. Benavie’s score makes use of several pieces of music such as Leroy Anderson’s “Irish Washerwoman” and “The Girl I left Behind Me”, Ludwig Van Beethoven’s Turkish March, Franz Schubert’s Military March, Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s Slavonic March, and also several original pieces by Benavie. The cartoon animation of Tommy Telephone is believed by many to have been done by Jim Tyer; other candidates possibly responsible for the animation consist of Rockwell Barness and Max Fleischer. Overall a clever and fun little film that is one of Handy’s best made during the post-World War II era; coincidentally made during the same year as the studio’s other notable cartoon, “Rudolf The Red-Nosed Reindeer”.

LIVE ACTION INDUSTRIAL FILMS (VARYING IN LENGTH) FEATURING STOP MOTION SEGMENTS

Precisely So (1937)

Precisely So (1937)

Sponsor: Chevrolet Sales Division-General Motors Corporation

Non-theatrical Distribution: Jam Handy Organization

JHO Completion Date: September 8, 1937

Copyright Date: No Copyright Records

Description: A documentary film that was created as an ‘’institutional’ for Jam Handy’s and Chevrolet’s ‘Direct Mass Selling’ film program that was in use from 1935 to 1942. Precisely So was one of three known two-reel documentary ‘institutionals’ produced for the program, the other two being The Master Hands (1936) and From Dawn To Sunset (1937). Unlike other formats in the ‘Direct Mass Selling’ program (such as the one reel documentary films, narratives, novelty newsreels, and Technicolor cartoons) which were created for both theatrical and non-theatrical exhibitions, ‘institutionals’ were created for non-theatrical exhibitions, geared mainly toward high schools or trade schools. The three films were produced at an interesting time period as not only were they made during the great depression but also around the time of the infamous Flint sit down strike of 1936-1937 at GM’s Fischer Body plant. While the films certainly meant to subliminally boost GM and Chevrolet’s image as a decent place to work and how they have benefited their workers lives, the institutionals were also created to encourage young adults and other students to not give in to the depression, and pursue respectable and skill driven manufacturing jobs.

Precisely So showcases how the talents of various engineers have lead to a better life in American society, most specifically through the design of precision based instruments. The film features beautiful cinematography (done by Gordon Avil, William Skall, or Pierre Mols) as well as powerful narration by Lowell Thomas. The true highlight of the film is the final two minutes which features a beautifully made and powerful stop motion sequence by Frank Goldman of a parade of precision instruments marching forward to the future. This sequence is further enhanced by a triumphant recording by Samuel Benavie of the third movement to Pytor Tchaikovsky’s sixth symphony.

Seeing Green (1937/38)

Sponsor: Chevrolet Sales Division-General Motors Corporation

Theatrical Distribution: Jam Handy Organization and Monogram Pictures

Non-theatrical Distribution: Jam Handy Organization

JHO Completion Date: November 15, 1937

Copyright Date: February 14, 1938

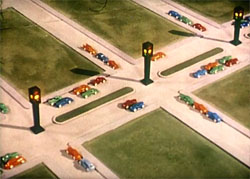

Original Number of Prints (as indicated by copyright records): 44

Description: Lowell Thomas narrates this one reel documentary ‘Direct Mass Selling’ entry, that puts to use the black & white to color story telling technique to discuss the progress and future of traffic light technology. (It should be noted that at the time of the production and release of this film, there were no standardized consistent traffic light systems located across the nation. Every town and city had there own traffic light devices and protocols.) The first two thirds of the film which is black & white live action footage, discusses the traffic light: it’s benefits and technology, but also the issues and confusion with inconsistent devices across the country and emphasizes the interest to utilize a standardized scientifically engineered three color system. The majority of the cars used in the traffic light demonstrations are Chevrolet automobiles. In addition, the black & white sequence also demonstrates the technology of the proposed scientifically engineered three color system (still in use today with some modifications).

The final third of the film is a three-strip Technicolor stop motion sequence by Frank Goldman that demonstrates the perfect scientifically engineered three color traffic light system of the future. It also features a brief technical animation sequence at the very end by Rockwell Barnes showing off a realistic three-color traffic light. Overall, a very interesting film that cleverly utilizes the black & white to color technique. (Perhaps Mr. Handy had a vision that by the time the three-color traffic light system of the future would be in use, all films would be made in Technicolor…) While the stop-motion sequence is fun, the black & white shots of all of the different traffic light systems of the 1930s are fascinating to see. The film was distributed non-theatrically for exhibition at school events, community club meetings and factory luncheons and theatrically to movie houses by the Jam Handy Organization (booked by Chevrolet dealers). It was also distributed to cinemas and newsreel theaters as a short subject by Monogram Pictures, who handled distribution to many of the 1937 to 1942 direct Mass Selling films.

Auto-Lite On Parade (1940)

Sponsor: Electric Auto-Lite Company

Non-Theatrical and Theatrical Distribution: Jam Handy Organization

JHO Completion Date: June 4, 1940

Copyright Date: June 24, 1940

Original Number of Prints (as indicated by copyright records): 209

Description: An enjoyable documentary two-reeler that epically showcases the Electric Auto-Lite Company’s contributions to both the automobile industry and the American Way of life. The entire production was directed (and (probably produced) by former silent screen comedian turned industrial filmmaker J. Cullen Landis. Like other Pre-WWII era productions Landis directed for Jam Handy such as the studio’s notable 1939 Technicolor film for Coca-Cola Refreshment Through the Years, Auto-Lite on Parade makes use of all types of showmanship tricks with animation, visual effects, montages, super-imposing footage, etc. making the production visually entertaining. (Landis’ films beautifully execute one of Jamison Handy’s philosophies that “learning should be fun, and not a pain in the head). The film features beautiful cinematography by Pierre Mols, combined with an array of visual effects sequences by Frank Goldman and film editor Jon Kanan, all accompanied by a powerful soundtrack featuring Lowell Thomas’ narration and an original music score by Samuel Benavie. The film’s final four minutes is an elaborate stop motion parade of the Electric Auto-Lite Company’s products marching, synchronized to a triumphant recording by Benavie of Franz Schubert’s Military March. It should be noted that in the late 1940s, the film’s stop motion sequence was edited into various different television commercials the Jam Handy Organization produced for the Electric Auto-Lite Company. Auto-Lite On Parade was distributed non-theatrically for exhibition at school events, community club meetings and factory luncheons and theatrically to movie houses by the Jam Handy Organization (booked by Chevrolet and General Motors dealers and dealers of electric Auto-lite products). Though there is no official documentation available, it’s very likely that the film was also distributed to movie theatres and newsreel theatres by Monogram Pictures who handled distribution to many of Handy’s films created for public exhibition.

Aluminum On the March (1956)

Aluminum On the March (1956)

Sponsor: Reynolds Metals Company

Non-theatrical Distribution: Association Films

JHO Completion Date: April 4, 1956

Copyright Date: No Copyright Records

Description: One of the Jam Handy Organization’s best industrial documentaries of the 1950s. This twenty eight minute Eastman Color film showcases Aluminum produced by the Reynold’s Metals Company, and demonstrates how it is produced and used to improve the American way of life. To chronicle the story and benefits of Reynold’s Aluminum, the film makes use of various stop-motion sequences by Frank Goldman, beautiful cinematography (which may have been done by Reynold’s cinematographer Andrew Fain), powerful narration, and an original score by Samuel Benavie. Frank Goldman’s animation sequences range from parades of aluminum led by a Reynold’s R-Man to parades of various Aluminum products and other products which utilize aluminum packaging. While Goldman’s animation sequences are a lot of fun, the true highlight of the production is the cinematography and Benavie’s score that epically captures how Aluminum is mined and then produced in Reynolds’ various facilities located around the nation. Interestingly Benavie’s music score to Aluminum On The March is extremely similar sounding to Jam Handy’s 1956 Technicolor Superscope epic American Engineer, which was completed in early May of 1956 (A month after “Aluminum On The March”). Distribution of Aluminum On The March was carried out by Association films who distributed 16mm prints for non-theatrical screenings at schools and community club events booked by dealers of Reynold’s products and also for showings on local television Stations; it was not distributed theatrically. It should be noted that in 1953, Reynolds Metals reorganized into Reynolds International to compete on the international level, and its very well possible that the film was created to help market the company internationally.

OTHER WORK AND LEGACY

Along with producing the animation for the various films listed above, Frank Goldman also created brief animation sequences for a variety of different live action films to help visually break down concepts or visually enrich their content. Here’s three examples of some of these different types of productions:

• “Hold Everything” – A 1936 non-public film that was only shown to Chevrolet Dealers at regional meetings, that shows off the new Chevrolet advertising theme and slogan of 1937: “The Complete Car- Completely New”. The film discusses the plan of how the theme will be marketed utilizing the various forms of 1930s era mass communication (radio, newspapers, magazines, cinema, etc.). One scene at 8:28 on Prelinger’s transfer features a stop-motion sequence of various magazines of the era that carried Chevrolet Advertisements.

• “Machine Shop Work No. 4: Drilling, Boring and Reaming”– A 1941 training film sponsored by the United States Office of Education demonstrating how to drill, bore and ream a Taper utilizing various machines. The majority of the film was shot on location at the Greenfield Tap & Die Corporation in Greenfield Massachusetts, who was the lead producer of taps and dies in the country. The film features extremely short stop motion sequences at 2:34 and 10:22 of the Taper

• “The Kingdom of Plastics”– A 1945 Technicolor “GE Excursion in Science” one-reel short made for nontheatrical and theatrical public exhibition that discusses plastics: what they are, how they are made, how they helped the United States win the second World War, and how they will be used during the post-War era. The film utilizes a stop motion segment at 4:10 with ‘building block’ molecules to show how plastics are joined together and produced.

In addition to all of these small sequences, Goldman also oversaw the production of several stop motion television commercials that were produced for various clients in the late-1940s. Some sources such as Business Screen Magazine even credit many of these films as being the first commercials to be made specifically for television. Two of the more well known and existing examples of Goldman’s television commercials consist of two different (American Tobacco Company) Lucky Strike Cigarette commercials: one that featured marching cigarettes and another that featured square dancing cigarettes. Along with these two films, there were a number of other stop motion commercials made for other clients such as Electric Auto-Lite, Scotch Tape and many other clients, that unfortunately remain unaccounted today.

Frank Goldman retired from the Jam Handy Organization and from filmmaking all together in the late-1960s. A decision he made with the coming of old age and also with the lack of work coming into the Jam Handy Organization around the same time. Up until his retirement he worked on stop motion, and the visual effects, animation, etc. to many of Handy’s films. Today while many Jam Handy films that featured Goldman’s work have been made available for viewing and downloading by Rick Prelinger and other film collectors, many other films remain lost and unaccounted for. Until the 1960s the Jam Handy Organization turned out hundreds of films making it very likely that the studio produced other stop motion films and live action films with stop motion sequences. Unfortunately the studio’s records indicating who worked on what, were either lost or destroyed through the years making it difficult to compile a complete filmography of films Goldman worked on for Jam Handy.

In this modern era while the original purpose and needs of Frank Goldman’s Jam Handy films have long since passed, many still hold much educational, historic and entertainment value that has taken on a role of their own through the years. For example I recall when I was in high school (2000-2004) and experimenting with stop motion animation, studying Goldman’s Jam Handy stop motion that made use of simple toys and household products was always inspirational to me. As someone who was untalented in the craft of puppets, models, and clay figures it was often intimidating to study the work of George Pal, Ray Harryhausen, and Art Clokey. Frank Goldman on the other hand offered a more realistic and cheaper alternative to me and demonstrated that you could have fun animating common household objects. Other people have found enlightenment and entertainment value in many of Frank Goldman’s Jam Handy based work for various different reasons. One can only hope that Mr. Francis Lyle Goldman is pleased that his work has taken on a life of its own and is still being seen and used by many different people.

(A special thank you to Ray Pointer, Tom Stathes, Brian Oakes, Rick Prelinger, Chris Clawson and Steve Stanchfield.)

Jonathan A. Boschen is a professional videographer and video editor, who is also a film and theatre historian. His research deals with pre-1970s movie theaters in New England and also film history pertaining to the Jam Handy Organization, Frank Goldman, Ted Eshbaugh, Jerry Fairbanks, and industrial films. (He is a huge fan of industrial animated cartoons!). Currently, Boschen is working on a documentary on the iconic Jam Handy Organization.

Jonathan A. Boschen is a professional videographer and video editor, who is also a film and theatre historian. His research deals with pre-1970s movie theaters in New England and also film history pertaining to the Jam Handy Organization, Frank Goldman, Ted Eshbaugh, Jerry Fairbanks, and industrial films. (He is a huge fan of industrial animated cartoons!). Currently, Boschen is working on a documentary on the iconic Jam Handy Organization.

Clips from “Auto-Lite On Parade,” perhaps with some new sequences added, were the basis for the intros and commercials used on the early TV version of the radio show SUSPENSE, sponsored by Auto-Lite. There were also animated diagrams showing how and where Auto-Lite parts were used in cars (with “live” announcer Rex Marshall often desperately out of sync with the film he was narrating!) Auto-Lite commercials on the show also used line-art character animation showing the problems faced by drivers whose cars needed Auto-Lite spark plugs; the look and technique very similar to Sam Singer’s “Paddy Pelican” cartoons.

Tremendous post!!!

Although I can’t appreciate it now, I was always amused and amazed by how stop motion can seemingly bring to life inanimate objects, but this technique has been used with live people. I’d love to hear more about how that technique works. Do the humans have to hold poses and imagine themselves as “frames” in a cartoon? That might be a terrific topic to come.

The Auto-Lite film cuts off after 14 minutes. The whole film, including the march of the products, can be seen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YCe-HG4MoRg

Thanks Al – I’ve fixed the embed in the post above.

He is also the co-director,( as F. Lyle Goldman), with Max Fleischer of the 1929 Western Electric cartoon FINDING HIS VOICE .

Yes. That was made at the Carpenter-Goldman Lab facilities at the time that Max Fleischer had re-organized his studio after the bankruptcy closing of Out of the Inkwell Films, Inc. As “Fleischer Studios, Inc.” as of March, 1929, Frank offered space to Max for free and they were housed there for eight months before moving back to 1600 Broadway in November that same year.

I *still* say that Jim Tyer animated Tommy Telephone in “Just Imagine”, dammit.

Great to see Boschen return! Great post!

The Jam Handy film, Coca-Cola Refreshment Through the Years, can be found on this site.

https://www.1939nyworldsfair.com/Videos/History_of_Coca_Cola.htm