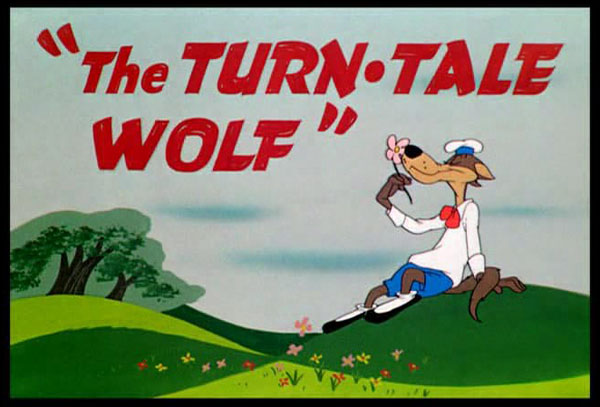

Here’s another fairy-tale spoof from Bob McKimson, where the Big Bad Wolf tells his version of ‘The Three Little Pigs’.

Elements of McKimson’s The Turn-Tale Wolf are similar to the earlier Friz Freleng cartoon The Trial of Mr. Wolf (1941). In both films, the Big Bad Wolf relays his account on how his prey from the original stories—in Trial’s case, Little Red Riding Hood and her furrier grandmother—carried malicious intentions against him. Moreover, in both films, the Big Bad Wolf depicts himself as a grown man acting like a naïve schoolboy, dressed in a sailor suit to accentuate his potential falsehood.

Elements of McKimson’s The Turn-Tale Wolf are similar to the earlier Friz Freleng cartoon The Trial of Mr. Wolf (1941). In both films, the Big Bad Wolf relays his account on how his prey from the original stories—in Trial’s case, Little Red Riding Hood and her furrier grandmother—carried malicious intentions against him. Moreover, in both films, the Big Bad Wolf depicts himself as a grown man acting like a naïve schoolboy, dressed in a sailor suit to accentuate his potential falsehood.

In McKimson’s film, the Three Little Pigs — carryovers from an earlier 1949 McKimson cartoon The Windblown Hare — act as bullies towards the Wolf, immersing in destructive games to harm the wolf in every direction. (Their torture couldn’t be more overt than their game of “Swat the Fly,” with the Wolf playing the obvious victim to the Pigs’ swatting/paddling, brilliantly animated by Rod Scribner.)

Tedd Pierce, McKimson’s main writer during this period, is credited on the story for The Turn-Tale Wolf. Recollections of Pierce revealed a predilection towards alcoholic drinks, appropriate enough for the Big Bad Wolf’s introduction as he fills up a jug from his homemade moonshine still. Pierce was born on Long Island in 1906, and his family moved to Pasadena by 1910, where he received a prep school education. He wrote for the Los Angeles Daily News and spent a year in Tahiti before joining the Schlesinger studio in 1933. Besides providing material for the directors in the general pool of story men, Pierce also lent his voice for several of the Warners cartoons, including the Wolf in Tex Avery’s Little Red Walking Hood (1937) and the Major in Frank Tashlin’s The Major Lied ‘Til Dawn (1938). Pierce left for the Fleischer studio in Miami in the late ‘30s, working on the studio’s two feature productions, Gulliver’s Travels and Mr. Bug Goes to Town, along with their other theatrical shorts. He also voiced King Bombo in Gulliver and the Edward Arnold-esque C. Bagley Beetle in Mr. Bug.Pierce returned to Warners in June 1941, writing cartoons for Chuck Jones and Friz Freleng. He continued to lend his voice in the cartoons—for instance, as Leo the Lion in Jones’ Hold the Lion Please (1942), among others throughout the ‘40s. He shared credit with Mike Maltese on stories for the two directors, but their collaboration disbanded after an argument. Pierce remained as Freleng’s story man until 1949, when the studio moved him into McKimson’s unit. Shortly before Warners shut down its animation department in 1953, Pierce had left for UPA as a writer, credited on such films as Fudget’s Budget (1954) and the Academy-Award winner When Magoo Flew (1954). Pierce’s time at UPA was short; he returned to Warners when it re-opened on January 1954. In the early ’60s, Pierce left again to work as a writer for Walter Lantz, some time after Maltese and Warren Foster left for Hanna-Barbera.

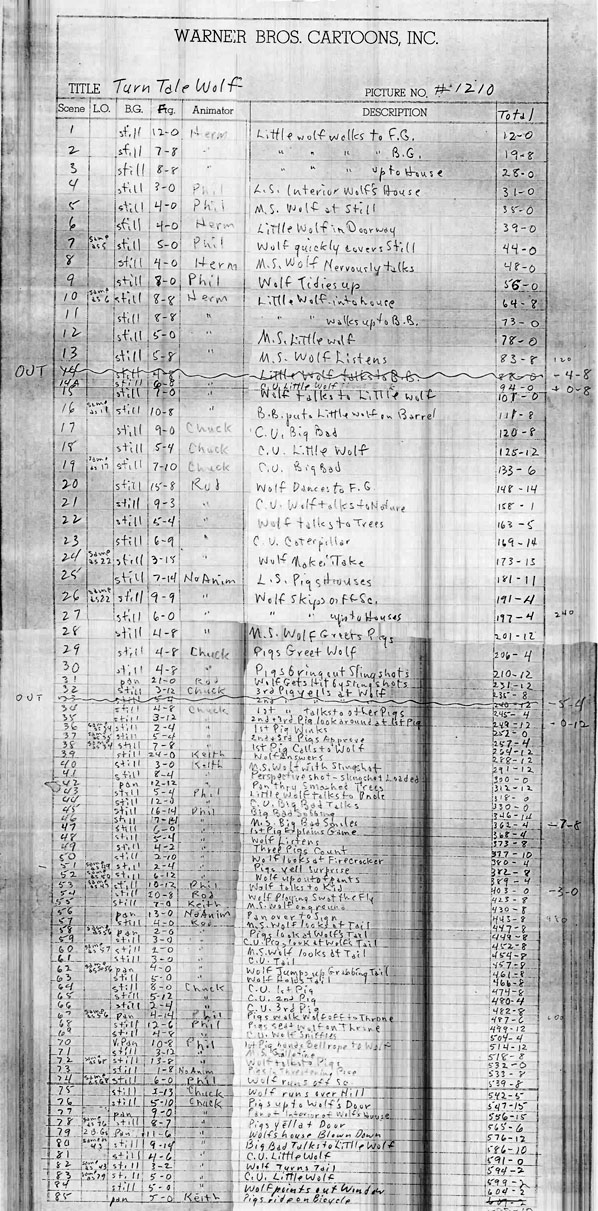

Herman Cohen, credited for his work on the main titles, is only given the opening portions of the film, when the Big Bad Wolf’s nephew comes home from school, displeased after learning about his uncle’s malevolent past. Besides the “Swat the Fly” game, Rod Scribner is assigned to some convincing character acting in the film, with his usual eccentric, grotesque drawings. He animates the “goody-goody” Big Bad Wolf’s fondness of nature before passing the Three Little Pigs’ houses, and fussily retorting them after being hit by their slingshots. Later in the film, after the pigs witness a $50 bounty for a wolf’s tail, he clutches onto his own, knowing his friends have the notion of detaching it. (Scene 73, the pigs’ “threatening pose,” ready to charge after the wolf, is priceless.) Like Rabbit’s Kin, Keith Darling is un-credited for his work on the film, animating the slingshot game. Though he isn’t given much footage, Darling’s drawing/animation—like Rabbit’s Kin, too—possesses a look similar to Jones’ cartoons, and isn’t constricted by McKimson’s layouts, like his brother Charles or Phil De Lara’s work.

Herman Cohen, credited for his work on the main titles, is only given the opening portions of the film, when the Big Bad Wolf’s nephew comes home from school, displeased after learning about his uncle’s malevolent past. Besides the “Swat the Fly” game, Rod Scribner is assigned to some convincing character acting in the film, with his usual eccentric, grotesque drawings. He animates the “goody-goody” Big Bad Wolf’s fondness of nature before passing the Three Little Pigs’ houses, and fussily retorting them after being hit by their slingshots. Later in the film, after the pigs witness a $50 bounty for a wolf’s tail, he clutches onto his own, knowing his friends have the notion of detaching it. (Scene 73, the pigs’ “threatening pose,” ready to charge after the wolf, is priceless.) Like Rabbit’s Kin, Keith Darling is un-credited for his work on the film, animating the slingshot game. Though he isn’t given much footage, Darling’s drawing/animation—like Rabbit’s Kin, too—possesses a look similar to Jones’ cartoons, and isn’t constricted by McKimson’s layouts, like his brother Charles or Phil De Lara’s work.

Mel Blanc recorded the dialogue for this cartoon in two consecutive sessions, on July 31 and August 5, 1950. There is no evidence on when the musical score was recorded. Carl Stalling uses some clever motifs in the cartoon, including Alphons Czibulka’s “Hearts and Flowers,” a composition synonymous with insincere displays of tragedy. This piece plays underneath the Wolf telling his nephew about how the story of the Three Little Pigs was a “bum rap”. Stalling’s usage of popular music could be literal for suitable scenes in the Warners cartoons, as well. The 1921 hit tune “Ain’t We Got Fun” (Richard A. Whiting/Raymond B. Egan/Gus Kahn) plays during the slingshot and the “surprise, surprise” game—fun for the tormenting pigs but unpleasant for the Wolf.

Mel Blanc recorded the dialogue for this cartoon in two consecutive sessions, on July 31 and August 5, 1950. There is no evidence on when the musical score was recorded. Carl Stalling uses some clever motifs in the cartoon, including Alphons Czibulka’s “Hearts and Flowers,” a composition synonymous with insincere displays of tragedy. This piece plays underneath the Wolf telling his nephew about how the story of the Three Little Pigs was a “bum rap”. Stalling’s usage of popular music could be literal for suitable scenes in the Warners cartoons, as well. The 1921 hit tune “Ain’t We Got Fun” (Richard A. Whiting/Raymond B. Egan/Gus Kahn) plays during the slingshot and the “surprise, surprise” game—fun for the tormenting pigs but unpleasant for the Wolf.

The cartoon was released in theaters on June 28, 1952—nearly two years after the dialogue track was recorded. The last three scenes listed on the draft for The Turn-Tale Wolf reveal an alternate ending, where the Three Little Pigs are seen again outside of the Wolf’s house, riding a bicycle. Of course, it’s unclear what the original final gag would have been, but it could have been fully animated since the scene is credited to Keith Darling. The Wolf’s closing line at the end of the film is satisfying enough, as is.

Enjoy!

(Thanks to Michael Barrier and Yowp for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

The use of “Song of the Mounted Police” when Big Bad is led to his throne is an odd choice. I wonder why Carl Stalling didn’t use “King for a Day” instead, especially considering the pigs said those exact words beforehand.

I’m glad to see these Looney Tunes video breakdowns back, I was missing them. Do you have any from the post-53 shutdown era?

The Three Little Pigs aren’t the only carryovers from “The Wind-Blown Hare”-the wolf himself is,too. (Only in the first, Jim Backus started out doing the wolf’s first lines before Mel Blanc took over..and Backus was the exclusive voice for Smokey the Genie in another late 1940s McKimson Bugs-fairy tale tale spoof, “A Lad in his Lamp,1948”.)

This is one of Robert McKimson’s all-time funniest and one of my favorites!

but i don’t KNOW how to play surprize surprize

It seems to be no coincidence that both Wolf shorts are shown back-to-back on vol. 5 of the Looney Tunes Golden Collection, eh?

To answer Ian L.’s question above, when I was doing archival research at Warner Bros. /USC, I came across an intriguing note regarding this cartoon….it seems King For a Day was recorded by Blanc singing harmony with Treg Brown. Why this piece of track was discarded is anyone’s guess (rights issue?), but it certainly would have been a treat to hear.

Interesting! I don’t know why it would’ve been a rights issue, though; “King for a Day” was used in a couple other Looney Tunes cartoons: “What Makes Daffy Duck” and “The Prize Pest”.

Funny enough, the cue sheet for this cartoon lists “King for a Day” as part of the musical score, instead of “Song of the Mounted Police”.

I don’t think the melody of “King for a Day” would have fit the tone of the scene.

Sure are some truly disturbed drawings hidden in Scribner’s amazing “swat the fly” scene….

Although the bandage only appears in the final shot, kudos to McKimson and his animators for clearly showing that the Wolf in the present-day scenes has no tail, long before the subject comes up in the flashbacks. (He never tells the kid “This is the story of how I lost me tail” or anything)

Well the set-up was the kid being mad at his dad for being the bad guy anyway and for him to tell him from his side of the story. I suppose if you hadn’t noticed his tail-less appearance, it might’ve came off as a surprise towards the end if you went back.

Years later there was a children’s picture book The True Story Of The Three Little Pigs by Jon Scieszka, in which the wolf tells his side of the story.

I’m sure the notion of re-telling the tale from the wolf’s perspective is a unique and interesting diversion to what we already know, or not know.

Fantastic