Has there ever been a year in recent memory where we’ve been more anxious to shout “Out with the old”? If there were events to remember this season (with the possible exception of the Laker and Dodger victories), they all appear to be largely bad. It seems that Times Square will be “dropping the ball” to a rather empty house. (You’d have almost thought they could have taken a leaf from professional sports, and charged a fee to set up your cardboard image in attendance in the middle of the New York streets.) And, for us afficionados of the silver screen, will the theatre industry survive to once again allow us to enjoy our animated epics in multichannel widescreen presentations? Thus, we come to this first “virtual” New Year with a set of mixed emotions – and a feeble yet undaunted hope that something better will be coming for us round the bend – it’s almost at the stage where any change can’t possibly give us worse.

To continue to keep our spirits alive, our toon friends again remind us this week of times when celebrating was second-nature – and any excuse for festivities was a good one. Through their journeys back in time, we hope to boost your strength to give Father Time 2020 a swift kick in the pants, and to place a new Baby New Year on his (or her) rightful throne.

To continue to keep our spirits alive, our toon friends again remind us this week of times when celebrating was second-nature – and any excuse for festivities was a good one. Through their journeys back in time, we hope to boost your strength to give Father Time 2020 a swift kick in the pants, and to place a new Baby New Year on his (or her) rightful throne.

The witching hour of midnight plays a central role not only in the current holiday, but in a certain classic fairy tale lampooned no end by the animation industry. To put the two together, we’ll first examine an early silent “night out” that seems in step with the season, A Kick for Cinderella (Bud Fisher, Mutt and Jeff, 1926), the title of which lampoons the Paramount feature, A Kiss for Cinderella (1925), based on a stage play by James Barrie (of “Peter Pan” fame) and starring Betty Bronson. (The feature still exists and is on the internet, though only presently surviving in a dupey unrestored form.) As for the cartoon, we are basically presented with a “gender bender” send-up of the classic tale – something of the early-day equivalent to Jerry Lewis’s “Cinderfella”. Jeff, who has been reading a copy of “Cinderella”, is left to tend the home fires burning, in menial domestic drudgery and apron strings, while Professor Mutt leaves in top hat and tails to give a demonstration in Charleston dancing at the Dance Palace that evening. A funny shot shows Mutt en route to the event, appearing to be riding in a taxi – until the vehicle pulls ahead, revealing Mutt to actually be on foot behind the vehicle’s window in a brisk walk. (This gag would see parallels in later years at several other studios, including Donald Duck appearing to be riding in Greta Garbo’s limousine but actually just seated on its fender in “The Autograph Hound” (1939), and the opening credits of Hanna-Barbera’s “Top Cat” with T.C. similarly riding on the fender of a Rolls Royce.) Jeff cries and wails by the fireplace, but is surprised by a tap on the shoulder by a fairy godmother. Discovering Jeff wants to go to the dance exhibition, she waves her wand to transform Jeff’s apron strings and maid’s cap into topper and tails, then provides Jeff with a pair of magic shoes, with which she promises Jeff can outdance anybody. She transforms Jeff’s stool by the fireplace into a taxi cab, which roars through the wall and out to the exhibition, while Jeff receives the usual warning to be back before midnight or lose everything.

Mutt is cutting loose before a packed house at the ballroom, elastically craning his neck and limbs clear across the dance floor in wild gyrations. Just as he begins taking bows, who should enter the hall but Jeff, instantly stealing Mutt’s thunder with twists and turns twice as speedy as Mutt’s. He varies up his repertoire of steps with Egyptian harem-dance moves in a veil, and even the tails of Jeff’s coat detach themselves and perform some independent dance moves of their own. On the sidelines, Mutt gnashes his teeth, while the crowd coaxes Jeff on with cries of “More, more, MORE!” Portions of this film begin to predict items we are more familiar with from later days, giving every appearance of a Bluto vs. Popeye dance-sabotage sequence such as in “Morning, Noon, and Night Club” or “Kickin’ the Conga ‘Round”, as Mutt peels a banana, eats its contents, and tosses the peel onto the dance floor. Jeff briefly slips, but recovers quickly and graciously, not losing his audience. The banana peel develops a mind of its own, pursuing Jeff from one side of the hall to the other, with Jeff narrowly missing another misstep. He finally stoops to retrieve the hazard once and for all, tossing it away – directly into Mutt’s face. Mutt, sprouting devil’s horns, stoops to a new dirty trick – tying Jeff’s coattails around the trunk of a heavy potted palm. Jeff finds himself “rooted” to the spot, just as he also catches sight of the clock reading only fifteen minutes until Twelve. Jeff struggles to free himself, but the palm pot won’t budge. Jeff finally remembers a shaving razor which somehow has managed to be included within the pocket of his coat, and cuts away his own coattails to free himself. Jeff then engages in a funny and well-animated war with the hands of the large clock in the center of the ballroom. Jeff attempts to push the minute hand of the clock backwards, eventually using his whole body weight to sit on it, to prevent the clock from striking the hour. But the clock’s hour hand battles back, doubling its point into a fist, and striking Jeff multiple blows across the jaw to knock him off the clock and permit the midnight hour to sound. (Note the interesting visual artifacts around the character movements in this shot, forming a flickering halo of reflected light from the camera’s lighting mount – apparent evidence that the action was accomplished with two or maybe three layers of transparent cels which were not completely flattened, resulting in odd reflective patterns off the curls and puckers of the flexible celluloid.) Jeff’s coattails begin to be pulled away as if caught in the suction of an invisible vacuum. While Jeff tugs and clings to the coattails, his pants begin to fall down. Keeping hold of both tails and trousers at the same time is too much for Jeff – and he loses them both. Then his magic dancing shoes leave his feet. Jeff chases them across the hall, but they kick him in the rear end. (Hence, the title of the cartoon.) Jeff finally gets a grip on the shoes – but they vanish completely, right out of his hands. Now Jeff is left standing before the crowd in nothing but his underwear, and becomes a laughing stock. He wails and cries on the floor, bemoaning his humiliation – as the scene dissolves ack to home sweet home, where Jeff is right where we left him before the appearance of the fairy godmother – ctying in front of the fireplace. Mutt appears in a nightshirt and with candle, awakening Jeff from his crying jag. “You sap! Why don’t you go to bed?” Jeff rubs his eyes, finds himself back in the apron strings and cap, and is so relieved to find it was all a dream, he breaks into a wild and carefree Charleston dance, while Mutt twirls one finger around his own ear in the universal signal that Jeff must be crazy, and the scene irises out.

Mutt is cutting loose before a packed house at the ballroom, elastically craning his neck and limbs clear across the dance floor in wild gyrations. Just as he begins taking bows, who should enter the hall but Jeff, instantly stealing Mutt’s thunder with twists and turns twice as speedy as Mutt’s. He varies up his repertoire of steps with Egyptian harem-dance moves in a veil, and even the tails of Jeff’s coat detach themselves and perform some independent dance moves of their own. On the sidelines, Mutt gnashes his teeth, while the crowd coaxes Jeff on with cries of “More, more, MORE!” Portions of this film begin to predict items we are more familiar with from later days, giving every appearance of a Bluto vs. Popeye dance-sabotage sequence such as in “Morning, Noon, and Night Club” or “Kickin’ the Conga ‘Round”, as Mutt peels a banana, eats its contents, and tosses the peel onto the dance floor. Jeff briefly slips, but recovers quickly and graciously, not losing his audience. The banana peel develops a mind of its own, pursuing Jeff from one side of the hall to the other, with Jeff narrowly missing another misstep. He finally stoops to retrieve the hazard once and for all, tossing it away – directly into Mutt’s face. Mutt, sprouting devil’s horns, stoops to a new dirty trick – tying Jeff’s coattails around the trunk of a heavy potted palm. Jeff finds himself “rooted” to the spot, just as he also catches sight of the clock reading only fifteen minutes until Twelve. Jeff struggles to free himself, but the palm pot won’t budge. Jeff finally remembers a shaving razor which somehow has managed to be included within the pocket of his coat, and cuts away his own coattails to free himself. Jeff then engages in a funny and well-animated war with the hands of the large clock in the center of the ballroom. Jeff attempts to push the minute hand of the clock backwards, eventually using his whole body weight to sit on it, to prevent the clock from striking the hour. But the clock’s hour hand battles back, doubling its point into a fist, and striking Jeff multiple blows across the jaw to knock him off the clock and permit the midnight hour to sound. (Note the interesting visual artifacts around the character movements in this shot, forming a flickering halo of reflected light from the camera’s lighting mount – apparent evidence that the action was accomplished with two or maybe three layers of transparent cels which were not completely flattened, resulting in odd reflective patterns off the curls and puckers of the flexible celluloid.) Jeff’s coattails begin to be pulled away as if caught in the suction of an invisible vacuum. While Jeff tugs and clings to the coattails, his pants begin to fall down. Keeping hold of both tails and trousers at the same time is too much for Jeff – and he loses them both. Then his magic dancing shoes leave his feet. Jeff chases them across the hall, but they kick him in the rear end. (Hence, the title of the cartoon.) Jeff finally gets a grip on the shoes – but they vanish completely, right out of his hands. Now Jeff is left standing before the crowd in nothing but his underwear, and becomes a laughing stock. He wails and cries on the floor, bemoaning his humiliation – as the scene dissolves ack to home sweet home, where Jeff is right where we left him before the appearance of the fairy godmother – ctying in front of the fireplace. Mutt appears in a nightshirt and with candle, awakening Jeff from his crying jag. “You sap! Why don’t you go to bed?” Jeff rubs his eyes, finds himself back in the apron strings and cap, and is so relieved to find it was all a dream, he breaks into a wild and carefree Charleston dance, while Mutt twirls one finger around his own ear in the universal signal that Jeff must be crazy, and the scene irises out.

Another vintage celebration – or should I say binge? – was Felix Woos Whoopee (Pat Sullivan, Felix the Cat, 11/18/28 – Otto Messmer, dir.). The narrative provides no details as to who let the cat out – but commences by finding out hero at the big city “Whoopee Club”, the very structure of which rocks with the vibrations of the merrymaking transpiring inside. As the club’s doors open, Felix is seen leading a multi-species array of creatures in song, in an atmosphere of confetti and noisemakers so convivial to Bacchanalia that cats and mice cavort and imbibe side by side as equals. Felix wildly cuts a rug with a rabbit dancing partner, then they both down respective bottles of brew. There seems to be no telling how many drinks of what substance Felix polishes off, being entirely non-particular whether he is acquiring same by mug or bottle – or somebody else’s bottle (stealing one quart right out of a rabbit’s hand by snagging it with a party favor). Felix gets so lost in his party frenzy, he almost swallows a mouthful of tossed confetti. By the time 3:00 a.m. chimes, Felix is totally zonked, and even the descent out the club doorway (down a single step) causes Felix to fall flat on his face. Meanwhile, recurring cutaways inform us that Felix faces more than just the obstacle of trying to get home – as Mrs. Felix paces the floor in front of a Grandfather clock, rolling pin in hand, ready to teach the cavorting cat a lesson he’ll never forget.

Felix’s trek through the city streets may bring an instant case of deja vu, especially to fans of Warner Brothers cartoons – though in reality we are apparently seeing here the original, with the more familiar Warner cartoon counterpart being the film which was paying “homage” to this one. The title to which I refer for its blatant similarity is Harman and Ising’s You Don’t Know What You’re Doin’ (1931), the most memorable sequence of which is a finale where the inebriated Piggy experiences an elaborate case of the “D.T.’s”, with buildings and streets bending and swaying in creative distortions. Compare said sequence with this Felix, and you can see the visual origins of many of the concepts which would find their way into the H-I production. The skyline similarly sways in rhythm as Felix stumbles along a flexing background. A lamppost comes to life and gives Felix a snub – and then a flirtation – similar to a bucking lamppost in the Warner product. (Of course, seeing a lamppost come to life when drunk was itself not a new idea even in Sullivan’s hands – having been used as early as 1916 in Paul Terry’s “Farmer Al Falfa Sees New York”). And then, the lamppost transforms into a fire breathing dragon – a similar transformation of a street gutter appearing in the Warner cartoon. The conclusion is unavoidable that someone at the Warners’ staff had definitely seen this cartoon!

Felix’s trek through the city streets may bring an instant case of deja vu, especially to fans of Warner Brothers cartoons – though in reality we are apparently seeing here the original, with the more familiar Warner cartoon counterpart being the film which was paying “homage” to this one. The title to which I refer for its blatant similarity is Harman and Ising’s You Don’t Know What You’re Doin’ (1931), the most memorable sequence of which is a finale where the inebriated Piggy experiences an elaborate case of the “D.T.’s”, with buildings and streets bending and swaying in creative distortions. Compare said sequence with this Felix, and you can see the visual origins of many of the concepts which would find their way into the H-I production. The skyline similarly sways in rhythm as Felix stumbles along a flexing background. A lamppost comes to life and gives Felix a snub – and then a flirtation – similar to a bucking lamppost in the Warner product. (Of course, seeing a lamppost come to life when drunk was itself not a new idea even in Sullivan’s hands – having been used as early as 1916 in Paul Terry’s “Farmer Al Falfa Sees New York”). And then, the lamppost transforms into a fire breathing dragon – a similar transformation of a street gutter appearing in the Warner cartoon. The conclusion is unavoidable that someone at the Warners’ staff had definitely seen this cartoon!

But Felix’s troubles don’t stop there. Suddenly, he is seeing the street filled with marauding lions, elephants, and gorillas – and some weird hybrids of both these and other species (such as a winged ape). Milk bottles transform into snakes – then just as quickly become a speeding car. Felix is swallowed by a fish, who becomes a saxophone, then a walking trumpet with legs. Felix makes it to his front door just ahead of another weird monster, which posts itself outside his door in case he should decide to leave home again. Taking his feet off as if they were shoes, and placing his tail in a holder for canes and umbrellas, Felix attempts to tiptoe quietly upstairs – but the stairs depress like piano keys under his feet, bouncing him off with a crash onto the living room floor. From nowhere, the scene morphs to materialize a giant chicken, with whom Felix engages in a violent scuffle, getting the bird into a stranglehold. Another transformation reveals the reality – that Felix is on top of his bed, fighting a battle with his own feather pillow – and the whole events of the cartoon were merely a dream. However, this doesn’t stop Mrs. Felix from kicking poor Felix out of bed for disturbing her slumber, and a cuckoo in a wall clock chirps its ridicule at the confused cat, causing Felix to pull out a pistol from his nightshirt to silence the bird with one shot, for a starry black-out.

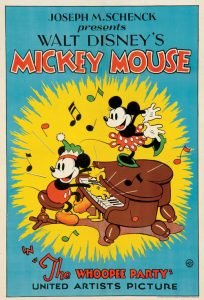

The Whoopee Party (Disney/UA. Mickey Mouse, 9/17/32 – Wilfred Jackson, dir.) is perhaps my favorite of all of Mickey’s party outings (most of which were presented last week). A bash is being held at Mickey’s house, which starts out politely enough – with a communal waltz, set to the tune of “Sweet Rosie O’Grady” performed by Minnie on piano and Clarabelle Cow on fiddle. Where are the boys? On the refreshment committee (referring to themselves as the “kitchen mechanics”), preparing a goodly supply of sandwiches. Horace Horsecollar inserts several plates into the venting slots of an old kitchen stove door, then uses the setup as a bread slicer to slice whole loaves into sandwich size in one stroke. Mickey slices ham with knife strokes that resemble the playing of a violin. Goofy (still at the time known as Dippy Dawg) stuffs olives into a hose, then sprinkles them over the sandwiches as garnishment. Mickey uses the segmented metal cover for the stove’s gas jets as a cake slicer to serve the dessert. The three parade their work into the living room, wearing pots on their head like soldiers’ helmets. Horace creates a drum rill with a pail on his chest and a rotating egg beater for a drumstick, while Goofy raises a curtain on the full banquet table of sandwiches and cake. Goofy and the table are swarmed by the hungry crowd, who leave the scene having drained the food supply dry – or so it seems, as Goofy, under the tablecloth, has preserved a fair share for himself by balancing the food atop his head. While several partygoers improvise musical instruments out of plumbing, old radiators, and stovepiopes, the dancers don’t even take a break to down their refreshments, instead continuing to dance with sandwices and cake in each hand, or plates baanced on their posteriors, allowing them to munch while they bunch.

The Whoopee Party (Disney/UA. Mickey Mouse, 9/17/32 – Wilfred Jackson, dir.) is perhaps my favorite of all of Mickey’s party outings (most of which were presented last week). A bash is being held at Mickey’s house, which starts out politely enough – with a communal waltz, set to the tune of “Sweet Rosie O’Grady” performed by Minnie on piano and Clarabelle Cow on fiddle. Where are the boys? On the refreshment committee (referring to themselves as the “kitchen mechanics”), preparing a goodly supply of sandwiches. Horace Horsecollar inserts several plates into the venting slots of an old kitchen stove door, then uses the setup as a bread slicer to slice whole loaves into sandwich size in one stroke. Mickey slices ham with knife strokes that resemble the playing of a violin. Goofy (still at the time known as Dippy Dawg) stuffs olives into a hose, then sprinkles them over the sandwiches as garnishment. Mickey uses the segmented metal cover for the stove’s gas jets as a cake slicer to serve the dessert. The three parade their work into the living room, wearing pots on their head like soldiers’ helmets. Horace creates a drum rill with a pail on his chest and a rotating egg beater for a drumstick, while Goofy raises a curtain on the full banquet table of sandwiches and cake. Goofy and the table are swarmed by the hungry crowd, who leave the scene having drained the food supply dry – or so it seems, as Goofy, under the tablecloth, has preserved a fair share for himself by balancing the food atop his head. While several partygoers improvise musical instruments out of plumbing, old radiators, and stovepiopes, the dancers don’t even take a break to down their refreshments, instead continuing to dance with sandwices and cake in each hand, or plates baanced on their posteriors, allowing them to munch while they bunch.

The music kicks into a higher gear, as Minnie and the improviso band perform Scott Joplin’s most popular composition, “Maple Leaf Rag”. Some animation is reused in this sequence, as Mickey again teams up with the rotund pig with whom he danced in “The Shindig”, reviewed last week. Most creatively, however, nearly every object in the house begins to take on a life of its own, joining in the beat of the music. Three lamps sway back and forth, alternating their on/off switches for lighting effect. A coat rack dances with a cushion-covered chair (I believe these designs would subsequently find their way into the furnishings of “Thru the Mirror”.) A roast chicken somehow still left on the banquet table tap dances while sandwiches, hot dogs, and coffee cups keep time with the rhythm. A coffee pot steams out the sound, “Hot cha cha cha”. Bundled shirts dance on their shirttails. Old socks and shoes stomp out the time. An old bed tosses around its pillows, while a chest of drawers puffs out its “chest”, tossing its drawers around. Even matches near the ash trays attempt to dance, but upon making contact, strike and blcken each other, reacting with a whisper of Al Jolson’s “Mammy”. The music now shifts to “Some of these Days”, as a bit of Clarabelle’s “mooing” dance is also reused from “The Shindig”, but reworked in two respects. First, Clarabelle now wears a full skirt, and has added three cowbells to her tail to make the occasion more festive. But additionally, Goofy pulls a prank on her, inserting the end of a roll-up party blower into a glove, then blowing the device to catch and tickle Clarabelle in the back, sending her moos into a new higher and more comical register. As Goofy laughs uproariously, Charabelle gets even, by inserting the end of a similar blower into a “loaded” boxing glove (with a horseshoe inside), and smacking Goofy in the face with it. The Goof gets knocked rear-end-first into a goldfish bowl, and giggles uncontrollably as the goldfish tickle his tail. Another musical shift, and the score transforms into “Runnin’ Wild”. (Watch for the repeated group shot of the impromptu orchestra as this tune begins, and note the goat who is at first absent, then suddenly reappears on the far left side of the frame.)

The music kicks into a higher gear, as Minnie and the improviso band perform Scott Joplin’s most popular composition, “Maple Leaf Rag”. Some animation is reused in this sequence, as Mickey again teams up with the rotund pig with whom he danced in “The Shindig”, reviewed last week. Most creatively, however, nearly every object in the house begins to take on a life of its own, joining in the beat of the music. Three lamps sway back and forth, alternating their on/off switches for lighting effect. A coat rack dances with a cushion-covered chair (I believe these designs would subsequently find their way into the furnishings of “Thru the Mirror”.) A roast chicken somehow still left on the banquet table tap dances while sandwiches, hot dogs, and coffee cups keep time with the rhythm. A coffee pot steams out the sound, “Hot cha cha cha”. Bundled shirts dance on their shirttails. Old socks and shoes stomp out the time. An old bed tosses around its pillows, while a chest of drawers puffs out its “chest”, tossing its drawers around. Even matches near the ash trays attempt to dance, but upon making contact, strike and blcken each other, reacting with a whisper of Al Jolson’s “Mammy”. The music now shifts to “Some of these Days”, as a bit of Clarabelle’s “mooing” dance is also reused from “The Shindig”, but reworked in two respects. First, Clarabelle now wears a full skirt, and has added three cowbells to her tail to make the occasion more festive. But additionally, Goofy pulls a prank on her, inserting the end of a roll-up party blower into a glove, then blowing the device to catch and tickle Clarabelle in the back, sending her moos into a new higher and more comical register. As Goofy laughs uproariously, Charabelle gets even, by inserting the end of a similar blower into a “loaded” boxing glove (with a horseshoe inside), and smacking Goofy in the face with it. The Goof gets knocked rear-end-first into a goldfish bowl, and giggles uncontrollably as the goldfish tickle his tail. Another musical shift, and the score transforms into “Runnin’ Wild”. (Watch for the repeated group shot of the impromptu orchestra as this tune begins, and note the goat who is at first absent, then suddenly reappears on the far left side of the frame.)

Mickey engages in some creative percussion work, rigging up a milk bottle xylophone, snapping a series of mousetraps (what are these doing in his home?), rattling transom windows and rolling up windowshades, all the while punctuating his performance with shouts of “Whoopee!” At last, someone finally calls the cops on these proceedings, and the town’s riot squad speeds to the scene in a paddy wagon. The police force barrels out of the wagon at Mickey’s doorstep, and we see the whole house vibrating from the sound of loud gunshots within. But as the camera follows inside, we discover that there is no violent confrontation going on. Instead, the police have come to join the party, rather than beat it, shooting their guns in wild celebration into the ceiling, swinging from the chandelier, and tapping their toes on every dancing surface imaginable. In center stage dance Mickey and Minnie, now both wearing honorary policeman’s helmets, who collide for another “Whoopee!” as the scene irises out. The staff can’t resist one last touch, adding a final shout of “Whoopee” at the conclusion of the end title music. (Two curious historical notes regarding this production. A surviving 16mm print from which original titles were derived by Dan Gerstein ends, despite the free-for-all rowdiness of this title, with a spliced-on certificate that the film was approved for screenings by an East Coast censorship board. And the film was the only original black and white cartoon to receive programming into an episode of Disney’s “House of Mouse”, run verbatim excepting an edit of the “Mammy” gag.)

Old King Cole (Disney/UA, Silly Symphony, 7/29/33 – David Hand, dir.), proves that the monarch of Fairytale land was indeed a Merry Old Soul. The events of the film transpire at an annual jamboree held at the palace for all the characters of nursery rhymes. A major element of the creative motif for this film’s art designs is the structuring of the residences of both the King and his subjects in the form of children’s “pop-up” books, where scenery and structures rise upon opening of the books’ pages as paper cutouts. While the execution of the animation of these paper wonders is a bit challenging for the ever-improving young Disney staffers of the day, coming off a bit more mechanical in motion than later productions such as “Mother Goose Goes Hollywood” would achieve in a few short years, it is nevertheless quite elaborate in detail, and must have popped the eyes of smaller studios such as Van Buren, whose Mother Goose efforts could never reach such sophistication. In this manner, we meet the Pied Piper (a very short time before his own installment in the Silly Symphony series), Little Boy Blue, the Crooked Man (in a delightfully crooked house), Old Mother Hubbard, and the Woman in the Shoe (whose “kids” we hope aren’t all hers, as the group of toddlers is depicted interracially (surprising this didn’t raise some eyebrows in Southern states of the day), along with walk-ons in a group shot for Little Red Riding Hood and the Wolf (who would also get their own appearances in the series about a year later), Goldilocks and the Three Bears (whom Disney bypased for later revisit, leaving the task to Iwerks, MGM, Warner Brothers and Terrytoons), Mary and her little lamb, and the Cat and the fiddle.

The design of Cole is, however, somewhat old hat. He is quite similar in design to 1932’s King Neptune, as well as using the identical basso voice. He is “toony” and round in dimension – something of a robed roly-poly. He welcomes the fairy folk to the ball, but reminds them that when midnight chimes, home to their books they must go. (Why? I didn’t see a fairy godmother transform them all from pumpkins.) Neverthelss. Cole commands that a pageant begin. The sequence is presented in an unusual form, as seemingly one continuous shot for several minutes of the film’s duration (though closer examination of the animation reveals slight shifts at several places in depth of camera zoom, denoting logical places where the animation could be cut from one artist to another. Nevertheless, the unusual length of the sequence must have left rival studios guessing how one or a few artists could possibly keep churning out the footage on what would have seemed an endless assignment for anyone in their own ranks. I wonder what a “Baxter’s Breakdowns” study might reveal as to how many artists actually contributed to this routine, and who did what.

The design of Cole is, however, somewhat old hat. He is quite similar in design to 1932’s King Neptune, as well as using the identical basso voice. He is “toony” and round in dimension – something of a robed roly-poly. He welcomes the fairy folk to the ball, but reminds them that when midnight chimes, home to their books they must go. (Why? I didn’t see a fairy godmother transform them all from pumpkins.) Neverthelss. Cole commands that a pageant begin. The sequence is presented in an unusual form, as seemingly one continuous shot for several minutes of the film’s duration (though closer examination of the animation reveals slight shifts at several places in depth of camera zoom, denoting logical places where the animation could be cut from one artist to another. Nevertheless, the unusual length of the sequence must have left rival studios guessing how one or a few artists could possibly keep churning out the footage on what would have seemed an endless assignment for anyone in their own ranks. I wonder what a “Baxter’s Breakdowns” study might reveal as to how many artists actually contributed to this routine, and who did what.

As performer after performer appear on stage, emerging out of Pandora’s box, a final act produces a teepee popping up, through the canvas of which emerge the heads of the ten little Indians. They begin to war whoop and beat tom tom rhythm, as they parade in single file in an Indian war dance. As they encircle the throne, Cole gets caught up in the tempo, and joins the dance with his own spirited war whoops. As he dances onto the ballroom floor, he gives a kick to the pumpkin shell of Peter Peter Pumpkin Eater, then partners up with Mary and her lambs, who are so small compared to the king that they can be lifted to dance across the girth of the King’s chest. A panning shot gives us another of those scenes which must have made everyone else in the industry wonder how you cou;d animate without everything appearing to be a minimal cycle an entire ballroom full of every nursery character imaginable dancing their shoes off as if there were no tomorrow. Old Mother Hubbard winds the King’s robes around him, then gives the robes a tug, sending the King into a spin like a top, right into the middle of an indoor fountain and pool in the center of the ballroom. However, the water does nothing to dampen the King’s spirits, and he reacts with a shout of “Whoopee!” But all good things must come to an end, as an uproar erupts in Pandora’s box, out of which pops a large grandfather’s clock, inhabited by three mice, curiously wearing Keystone cop helmets as law enforcement – Hickory, Dickory, and Dock. They announce that Twelve o’Clock has arrived – “You’ve had your fun. You’d better run” – then they enter the clock and begin ringing the hour on its internal chimes. The partygoers begin to exit helter skelter, with a dripping King Cole shaking hands as they pass and waving goodbyes. Several of the same characters we saw emerge from books are seen reentering them just before their pages close. (One of Mary’s little lambs has to be dragged into the pages by her crook to keep from getting shut out.) Cole beckons a fond goodbye to his subjects from the palace gate – then remembers something he almost overlooked. Producing an empty milk bottle, he leaves it just over the drawbridge for the milkman’s delivery, then hastens back inside the castle as Cole’s own storybook closes for the evening, leaving no sign of fairyland’s activities except the single empty milk bottle resting outside the book, for the iris out.

It’s almost obligatory – considering that it’s one of less than a handful of films to focus at all upon the New Year – to trot out each season Popeye’s Let’s Celebrake (Fleischer/Paramount. Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/William Henning, anim.), which actually hit the theatrical screen late for the season, on 1/21/38. It’s also surprising that Myron Waldman doesn’t receive an animator’s credit on this film, as the storyline is of the variety he would generally prefer – a departure from the usual cartoon violence of the series, in favor of a more peaceful and warm-hearted presentation. (I personally tend to prefer the more boisterous and action-packed approach of a Willard Bowsky.) Anyway, as often told, Popeye can’t stand the thought of Olive leaving her feeble, hard of hearing grandmother home alone with her knotting while Olive and the gang head out for some night life on New Year’s Eve – and abandons entirely his usual rivalry with Bluto for Olive’s affections, leaving the two of them to each other, while Popeye adopts Granny as his official date for the evening. At the Happy Hour Club, a Times Square-style neon sign depicts Father Time trudging toward a laundry wringer, into which he is pulled, compressing his outline into that of the baby New Year – literally “wringing’ out the old. In a reworking of concept from “The Dance Contest”, Popeye’s efforts to coax Granny onto the dance floor prove largely a bust, until he produces the all-curative spinach can, and administers Granny an elixir-like dose. Then, the sailor and septuagenarian are able to elaborately cut a rug to the amazement of the crowd – and most of all of Olive and Bluto – and carry off the dance trophy. A call from Wimpy announces the stroke of midnight, and the club is filled with balloons and confetti for a traditional finale.

It’s almost obligatory – considering that it’s one of less than a handful of films to focus at all upon the New Year – to trot out each season Popeye’s Let’s Celebrake (Fleischer/Paramount. Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/William Henning, anim.), which actually hit the theatrical screen late for the season, on 1/21/38. It’s also surprising that Myron Waldman doesn’t receive an animator’s credit on this film, as the storyline is of the variety he would generally prefer – a departure from the usual cartoon violence of the series, in favor of a more peaceful and warm-hearted presentation. (I personally tend to prefer the more boisterous and action-packed approach of a Willard Bowsky.) Anyway, as often told, Popeye can’t stand the thought of Olive leaving her feeble, hard of hearing grandmother home alone with her knotting while Olive and the gang head out for some night life on New Year’s Eve – and abandons entirely his usual rivalry with Bluto for Olive’s affections, leaving the two of them to each other, while Popeye adopts Granny as his official date for the evening. At the Happy Hour Club, a Times Square-style neon sign depicts Father Time trudging toward a laundry wringer, into which he is pulled, compressing his outline into that of the baby New Year – literally “wringing’ out the old. In a reworking of concept from “The Dance Contest”, Popeye’s efforts to coax Granny onto the dance floor prove largely a bust, until he produces the all-curative spinach can, and administers Granny an elixir-like dose. Then, the sailor and septuagenarian are able to elaborately cut a rug to the amazement of the crowd – and most of all of Olive and Bluto – and carry off the dance trophy. A call from Wimpy announces the stroke of midnight, and the club is filled with balloons and confetti for a traditional finale.

Though never formally designated as a New Year’s cartoon, Disney’s Woodland Café (Disney/UA, Silly Symphony, 3/13/37, Wilfred Jackson, dir.), perhaps more than any other cartoon, captures the spirit of a “pull out all the stops” celebration in a posh urban-center night-life venue – hitting a vibe far more festive and (dare I say it) more New Yorkan than even Fleischer. This although the actual venue is a night spot created for the insect world (and a few visiting gastropods). The scene opens on the Cafe’s neon sign – actually lit by an encirclement of fireflies. (This gag was borrowed, used as early as 1930 by Ub Iwerks in Flip the Frog’s The Soup Song.) A milling throng of insect life arrives by foot and by taxi at the doorway of the club. Inside, the hat check business is booming – especially when a centipede checks in an endless supply of white gloves for all of its many hands. An old but presumably wealthy bee (my suspicion is that his design may have provided some reference base for Fleischer’s later creation of C. Bagley Beetle for Mr. Bug Goes to Town) is escorted to a private table with a more youthful and beautiful girlfriend in tow. (Some have compared these characters to William Randolph Hurst and Marion Davies – take these comparisons as far as your imaginations and probability will permit.) A multi-handed head waiter attempts to take several dinner orders simultaneously, while lighting firefly lamps above the tables. On stage in the main ballroom, a jazzy grasshopper band warms up the crowd with a hot rendition of “12th Street Rag”. One funny shot shows the base fiddler – on an instrument which is built from an old browned autumn leaf with strinhs attached. The laugh comes when he is forced to shoo away a couple of young insects, who are nibbling away at one corner of his leaf as a part of their lunch. Drinks are served to the old bee, who approves a fresh red berry, from which the waiter pulls a stem like a cork to empty the contents into the bee’s glass.

Though never formally designated as a New Year’s cartoon, Disney’s Woodland Café (Disney/UA, Silly Symphony, 3/13/37, Wilfred Jackson, dir.), perhaps more than any other cartoon, captures the spirit of a “pull out all the stops” celebration in a posh urban-center night-life venue – hitting a vibe far more festive and (dare I say it) more New Yorkan than even Fleischer. This although the actual venue is a night spot created for the insect world (and a few visiting gastropods). The scene opens on the Cafe’s neon sign – actually lit by an encirclement of fireflies. (This gag was borrowed, used as early as 1930 by Ub Iwerks in Flip the Frog’s The Soup Song.) A milling throng of insect life arrives by foot and by taxi at the doorway of the club. Inside, the hat check business is booming – especially when a centipede checks in an endless supply of white gloves for all of its many hands. An old but presumably wealthy bee (my suspicion is that his design may have provided some reference base for Fleischer’s later creation of C. Bagley Beetle for Mr. Bug Goes to Town) is escorted to a private table with a more youthful and beautiful girlfriend in tow. (Some have compared these characters to William Randolph Hurst and Marion Davies – take these comparisons as far as your imaginations and probability will permit.) A multi-handed head waiter attempts to take several dinner orders simultaneously, while lighting firefly lamps above the tables. On stage in the main ballroom, a jazzy grasshopper band warms up the crowd with a hot rendition of “12th Street Rag”. One funny shot shows the base fiddler – on an instrument which is built from an old browned autumn leaf with strinhs attached. The laugh comes when he is forced to shoo away a couple of young insects, who are nibbling away at one corner of his leaf as a part of their lunch. Drinks are served to the old bee, who approves a fresh red berry, from which the waiter pulls a stem like a cork to empty the contents into the bee’s glass.

As in the night club circuit, as well as in several movie shorts of the day, the middle section of the performance is occupoed by a dance specialty act. Here, a seemingly vulnerable ladybug is preyed upon by an apache spider, dressed in traditional striped “sweater” in the French tradition. Resorting to everything from begging to commands, he attempts to lure the ladybug into his web, engaging in a spirited chase, as well as a full apache dance, tossing his dancing partner around and around. But the ladybug remains unharmed and unflappable, and eventually succeeds in tying up the spider in his own web. She assumes the spider’s position under a lamppost, now the new “big shot” of the neighborhood, as the curtain of leaves closes upon the number.

As in the night club circuit, as well as in several movie shorts of the day, the middle section of the performance is occupoed by a dance specialty act. Here, a seemingly vulnerable ladybug is preyed upon by an apache spider, dressed in traditional striped “sweater” in the French tradition. Resorting to everything from begging to commands, he attempts to lure the ladybug into his web, engaging in a spirited chase, as well as a full apache dance, tossing his dancing partner around and around. But the ladybug remains unharmed and unflappable, and eventually succeeds in tying up the spider in his own web. She assumes the spider’s position under a lamppost, now the new “big shot” of the neighborhood, as the curtain of leaves closes upon the number.

The finale pays direct tribute to New York’s famous “Cotton Club”, which had provided a steady venue for perhaps the most prestigious act to grace the Harlem circuits – Duke Ellington and his orchestra. Paying a direct musical royalty, the Ellington composition “Truckin’” is woven into the score for the Grasshopper orchestra. The dancers break into wild abandon. One of the club staff gathers fireflies into a suspended rotating ball in the club’s ceiling, producing a classic ballroom lighting effect. Worms wriggle and bump bodies against one another, while an elderly pair of snails dance at half-tempo. Mr. Bee even tries to accompany the spirited swaying of his girlfriend. At first, his ankles look like they will buckle in from lack of current use. They finally loosen up, to the point where Mr. Bee is dancing on the table, but leaving noticeable traces of smoke as his joints develop friction in places they’ve never used. His final shot depicts him being carried off by a team of paramedics, his shoes worn through and still smouldering. Yet Mr. Bee wears a weary but satisfied smile as he departs. Puff balls rain from the sky like balloons, as the band reaches a zenith of swing rhythm, alternating brass riffs against cymbal beats (all acrually played on flowers), and ending with a full screen cymbal crash and a shout of “Yeah!” for the iris out.

Rabbit Every Monday (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 2/10/51 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir. and story), on its surface seems an odd inclusion into this trail. However, its surprise ending definitely qualifies. The film is actually minimalistic in plot, merely providing a typical hunting setting and opportunity for the personalities of Bugs and Yosemite Sam to clash, as Yosemite trails Bugs in backwoods country, upsetting Bugs’ culinary exercises in simmering carrots over an open fire rotisserie-style, complete with basting and a twist of lemon. (”Oh, carrots are divine. You get a dozen for a dime. It’s MAAAA-GIC!”). Yosemite finally captures the rabbit by sifting him out of the unearthed soil surrounding him in his burrow, and marches the rabbit to his rustic cabin. There, he orders Bugs to enter an old wood-burning stove. With gun to his chest, Bugs has little choice. A gleeful Yosemite begins setting the dinner table, until Bugs emerges from the stove to retrieve an electric fan and a pitcher of ice water, commenting, “Hot in ‘dere.” “Quit stalling and start roasting”, demands Yosemite. Then things get strange. Bugs opens the stove door again, asking Sam if he has a bottle opener. Meanwhile, a distant Charleston-tempo rendition of “Cuddle Up a Little Closer” is heard by an orchestra from within the stove! A puzzled Yosemite provides Bugs with the requested utensil. After a pause. Sam’s curiosity draws him closer to the stove to investigate – but Bugs emerges again, muttering “Gotta have some cracked ice and a few more chairs.” He retrieves the items while more music plays from the oven’s interior. As Bugs reenters and the door closes again, Yosemite keenly listens outside the door in hope of learning just what is going on. Bugs again appears, carrying two large filled ash trays loaded with cigarette butts.

He steps on Sam’s shoe, which opens the top of Sam’s hat like a trash can. Bugs empties the waste into Sam’s hat, and asks him to be a pal and scare up a few more ash trays. Now Yosemite is burning with curiosity and frustration, but just as he is about to yank the door open, Bugs appears again, his face covered in lipstick marks from receiving several kisses. “Ain’t’cha comin’ in, Mac? The girls have been askin’ for ya”, says Bugs. “Well, hold the phone”, reacts a flattered Yosemite, sprucing himself up to make himself publicly presentable. “Hey, goils, da life of da party’s here!”, calls Bugs Into the stove, pushing Sam inside and slamming the door. Bugs decides to “heat the party up” for Sam by adding a few more logs to the fire. But his conscience makes him pause, and realize he couldn’t do that to the “little Nimrod”. “Come on out, Mac. It’s all just a gag”, says Bugs, opening the stove. He rears back in shock, as a red balloon floats out the oven door. The previously-heard orchestra has now risen in volume and clarity, and is playing the familiar New Years’ strain of Auld Lang Syne. As Bugs peers in, we see from his point of view a live-action shot (from Romance on the High Seas) of a lavish and wild New Years’ Eve party, and hear the voice of Sam hollering, “What a party!” The shot returns to the stove’s exterior, as Bugs rushes back inside the stove – emerging a moment later with a party hat on and twirling a noisemaker. “I don’t ask questions. I just have fun!”, he informs the audience, then disappears into the stove for the iris out – where we can only hope he and Yosemite continue to have a “hot time”. (This film left a certain legacy at another studio, as its oven sequence, complete with the request for ice water, was reworked by Jack Hannah for a principal sequence of Woody Woodpecker’s “Gabby’s Diner”, where Gabby Gator passes off the oven as the “elevator to room 350″ (degrees, that is).)

Being in charge of setting the parameters for these trails carries with it the perk of being able to bend your own rules. Despite there being practically no screen time for actual footage of celebration, I see here the opportunity to spotlight a New Years’ cartoon which oddly has not to my knowledge received print space on this website before, and which, without a little rule bending, may never appropriately fit in another animation trail – Sappy New Year (Fox/Terrytoons, Heckle and Jeckle, 11/10/61 – Dave Tendlar, dir.). A simple but clever premise frameworks this episode, focusing upon the subject of the New Years’ resolution, rather than upon the Bohemian extravagance of the night before. As the town rings in the new year, a barrel is being filled outside the residence of the two magpies, with an assorted collection of firecrackers, skyrockets, and dynamite sticks. As the barrel reaches capacity. Heckle, who has been in charge of the filling, calls to Jeckle – “Well, there go the last of out practical jokes, chum. Are you sure we’re doing the right thing?” “A resolution is a resolution, old featherhead”, states Jeckle, just completing the penning of a formal document, containing their resolve to abstain through the coming year from all gags and practical jokes. He asks Heckle to sign the instrument. “After you, chum” says Heckle, providing his pal with a “pen”, the barrel of which is a lit firecracker! Jeckle spots the nefarious instrument just in time, and blows out the fuse. Tossing it back to Heckle, Jeckle instructs, “Now throw it away.” Heckle almost does – but not before lighting the fuse again. Jeckle again blows out the flame before Heckle can toss the weapon out the window, and chastises Heckle for his behavior. “But Jeckle, it ain’t normal for us to…” Heckle at least convinces Jeckle to allow him to keep the firecracker in his pocket, as a remembrance for old times sake. “For once, we retire with a clear conscience” says Jeckle, as they nod off to sleep.

Being in charge of setting the parameters for these trails carries with it the perk of being able to bend your own rules. Despite there being practically no screen time for actual footage of celebration, I see here the opportunity to spotlight a New Years’ cartoon which oddly has not to my knowledge received print space on this website before, and which, without a little rule bending, may never appropriately fit in another animation trail – Sappy New Year (Fox/Terrytoons, Heckle and Jeckle, 11/10/61 – Dave Tendlar, dir.). A simple but clever premise frameworks this episode, focusing upon the subject of the New Years’ resolution, rather than upon the Bohemian extravagance of the night before. As the town rings in the new year, a barrel is being filled outside the residence of the two magpies, with an assorted collection of firecrackers, skyrockets, and dynamite sticks. As the barrel reaches capacity. Heckle, who has been in charge of the filling, calls to Jeckle – “Well, there go the last of out practical jokes, chum. Are you sure we’re doing the right thing?” “A resolution is a resolution, old featherhead”, states Jeckle, just completing the penning of a formal document, containing their resolve to abstain through the coming year from all gags and practical jokes. He asks Heckle to sign the instrument. “After you, chum” says Heckle, providing his pal with a “pen”, the barrel of which is a lit firecracker! Jeckle spots the nefarious instrument just in time, and blows out the fuse. Tossing it back to Heckle, Jeckle instructs, “Now throw it away.” Heckle almost does – but not before lighting the fuse again. Jeckle again blows out the flame before Heckle can toss the weapon out the window, and chastises Heckle for his behavior. “But Jeckle, it ain’t normal for us to…” Heckle at least convinces Jeckle to allow him to keep the firecracker in his pocket, as a remembrance for old times sake. “For once, we retire with a clear conscience” says Jeckle, as they nod off to sleep.

The next morning, Jeckle faces a bright new world with the prospect of presenting themselves as model citizens. Heckle passes a man looking into a store window – and can’t resist placing the lit firecracker in the man’s hip pocket. Jeckle once again blows out the fuse, and Heckle begs for understanding. “Give me time. Give me time1″ Jeckle spots a chance to perform a good deed – an old man waiting at a street corner. Picking the man up bodily, they transport him into busy street traffic, terrorizing him as they wend their way to the opposite side, depositing him unharmed on the opposite corner. “I didn’t want to cross the street. I was waiting for a bus!”. he complains. To make things right, the two carry him across the street again, tossing him into the open rear window of a bus that pulls up. “Another of your practical jokes”, yells the man. “This is the wrong bus1″ and the birds get whacked on the head by the man’s umbrella for their troubles. “Why that…”, mutters Heckle, pulling out the firecracker again. But Jeckle grabs it away before Heckle can light it, pointing out “People need time to get used to the new us.”

The next morning, Jeckle faces a bright new world with the prospect of presenting themselves as model citizens. Heckle passes a man looking into a store window – and can’t resist placing the lit firecracker in the man’s hip pocket. Jeckle once again blows out the fuse, and Heckle begs for understanding. “Give me time. Give me time1″ Jeckle spots a chance to perform a good deed – an old man waiting at a street corner. Picking the man up bodily, they transport him into busy street traffic, terrorizing him as they wend their way to the opposite side, depositing him unharmed on the opposite corner. “I didn’t want to cross the street. I was waiting for a bus!”. he complains. To make things right, the two carry him across the street again, tossing him into the open rear window of a bus that pulls up. “Another of your practical jokes”, yells the man. “This is the wrong bus1″ and the birds get whacked on the head by the man’s umbrella for their troubles. “Why that…”, mutters Heckle, pulling out the firecracker again. But Jeckle grabs it away before Heckle can light it, pointing out “People need time to get used to the new us.”

More efforts at good deeds backfire. An attempt to get a woman’s stalled car going shifts the vehicle into the wrong gear, causing a six-car chain reaction collision around the perimeter of a rotary, and rolling a runaway car back over the magpies themselves. A cop cautions them that there’ll be no more practical jokes on his beat. An attempt to rescue a kitten treed by a tough dog gets the birds chewed and clawed by both the dog and the cat. Next they smell smoke from an upper story home window. “And where there’s smoke, there’s fire”, says Jeckle. As they race toward the scene, they pass by another building where a painter stands on a tall ladder, paining the side of the building. The painter suddenly finds himself traveling sideways, as the magpies borrow the ladder for their rescue with him along for the ride. As they reach the smoky window, we see inside that there is only a man smoking a large pipe. As he looks out the window, the ladder arrives – and the painter’s brush splashes green paint across the man’s face. The angry smoker takes the painter’s paint can and inverts it atop the painter’s head, slamming him down the ladder to land on the magpies. The angry painter dumps the remainder of the paint can onto Heckle, stating “You birds don’t know when to stop with the gags.” “I’ve had enough”, says Heckle. “From now on, I’m back to my old personality.” Out comes the firecracker again. “We’ve got to give the resolution one more try”, says Jeckle, “but first, I’m getting rid of this temptation.” Grabbing away the firecracker before Heckle can light it, Jeckle tosses it over his shoulder. The firecracker comes to rest on the ground outside their own house, unfortunately landing next to a freshly-tossed – and still glowing – cigarette butt. The fuse is ignited, and the firecracker goes pop – landing directly in the barrel loaded with their TNT and skyrockets. With a loud explosion, the barrel vibrates to life, flips on its side, and rolls headlong down the street, explosives and skyrockets shooting out of the whirling fireball from both sides. The magpies watch in helpless amazement, as both sides of the city street and its vehicles are laid in waste. The barrel keeps rolling down to the docks, and rolls off the end of the pier into the ocean, leaving a trail of bubbles on the sea. But is the water enough to extinguish the contents? Hardly – as a large ship on the horizon is blown in two from an underwater explosion, and sinks into the bay. The birds now find themselves in an altogether too familiar situation – with the entire town pursuing them as an angry mob. “Oh well,”, says Jeckle as they speed a hasty retreat, “It was a good try, wasn’t it?”

More efforts at good deeds backfire. An attempt to get a woman’s stalled car going shifts the vehicle into the wrong gear, causing a six-car chain reaction collision around the perimeter of a rotary, and rolling a runaway car back over the magpies themselves. A cop cautions them that there’ll be no more practical jokes on his beat. An attempt to rescue a kitten treed by a tough dog gets the birds chewed and clawed by both the dog and the cat. Next they smell smoke from an upper story home window. “And where there’s smoke, there’s fire”, says Jeckle. As they race toward the scene, they pass by another building where a painter stands on a tall ladder, paining the side of the building. The painter suddenly finds himself traveling sideways, as the magpies borrow the ladder for their rescue with him along for the ride. As they reach the smoky window, we see inside that there is only a man smoking a large pipe. As he looks out the window, the ladder arrives – and the painter’s brush splashes green paint across the man’s face. The angry smoker takes the painter’s paint can and inverts it atop the painter’s head, slamming him down the ladder to land on the magpies. The angry painter dumps the remainder of the paint can onto Heckle, stating “You birds don’t know when to stop with the gags.” “I’ve had enough”, says Heckle. “From now on, I’m back to my old personality.” Out comes the firecracker again. “We’ve got to give the resolution one more try”, says Jeckle, “but first, I’m getting rid of this temptation.” Grabbing away the firecracker before Heckle can light it, Jeckle tosses it over his shoulder. The firecracker comes to rest on the ground outside their own house, unfortunately landing next to a freshly-tossed – and still glowing – cigarette butt. The fuse is ignited, and the firecracker goes pop – landing directly in the barrel loaded with their TNT and skyrockets. With a loud explosion, the barrel vibrates to life, flips on its side, and rolls headlong down the street, explosives and skyrockets shooting out of the whirling fireball from both sides. The magpies watch in helpless amazement, as both sides of the city street and its vehicles are laid in waste. The barrel keeps rolling down to the docks, and rolls off the end of the pier into the ocean, leaving a trail of bubbles on the sea. But is the water enough to extinguish the contents? Hardly – as a large ship on the horizon is blown in two from an underwater explosion, and sinks into the bay. The birds now find themselves in an altogether too familiar situation – with the entire town pursuing them as an angry mob. “Oh well,”, says Jeckle as they speed a hasty retreat, “It was a good try, wasn’t it?”

A final word of note on possible story derivation for this cartoon. With the input of Dave Tendlar, long associated with Paramount/Famous, on this cartoon, it is highly possible that Dave was looking over his shoulder back at the past product of his Paramount stablemates when this cartoon was conceived. The idea of a “good deeds all gone wrong” storyline had been similarly penned two years earlier in a Casper production of Seymour Kneitel, Not Ghoulty (1959), with Casper forced to attempt good deeds the hard way, due to a court-sentenced loss of his ghostly powers, and losing friends right and left when his strictly mortal efforts to do things right go wrong. Tendlar’s clever reimagining of the idea as a new concept for the magpies thus may in fact be indication that a fresh new idea was still unlikely to arise from within the traditional ranks of the Terrytoons studio, but instead more probably bore the earmarks of branding from the rival Famous staff from across town.

Short and sweet. Hoping everyone finds an improvement for the coming year over what we’ve been through. Glad you’ve been along for the ride down this year’s many trails, and we’ll continue to explore new terrains and byways as we saddle up for the coming season.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Thanks very much, Charlie.

The music that plays during the first half of “A Kick for Cinderella” is “Beautiful Ohio”, the Buckeye State’s official song (even though the lyrics refer to the river, not the state). It seems rather arbitrary and incongruous in this context, especially when Mutt is dancing the Charleston to that sentimental waltz tune. The second half of the cartoon, with its jazzy music and sound effects, is a big improvement.

Toward the end of “The Whoopee Party”, a pig is playing a makeshift horn made from a hose and a funnel; and believe it or not, one can really play music on such a contraption. At the first of the Hoffnung Festivals in London in 1956, which combined classical music with comedy and featured many major artists, horn virtuoso Dennis Brain played the alphorn solo in Leopold Mozart’s Sinfonia Pastorella on that very device, calling it a “hosepipe”. Years later, composer Peter Schickele used it in the humorous works of his alter ego, P. D. Q. Bach. I wonder if they got the idea from “The Whoopee Party”.

The police shooting their guns into the air at the end of that cartoon remind me that in Detroit, people ring in the New Year doing just that, or at least they used to. I played a New Year’s Eve gig in Detroit’s Greektown in the eighties, and the gunfire started right at twelve and went on all night. You never saw a band pack up the van so fast.

I remember how I marveled at the animation in “Let’s Celebrake” when I first saw it as a teenager. I still marvel at it now. I’m with you on the Waldman vs. Bowsky question, but Kneitel also created some true masterpieces, “The Spinach Overture” being a personal favourite.

There was a New Year’s episode of Disney’s “Phineas and Ferb”, even though the show was all about the boys finding ways to pass the time during their summer vacation. The typically elaborate plot has the boys making a giant New Year’s Eve ball, which they intend to drop from outer space; meanwhile, the evil Dr. Doofenshmertz constructs a device called the Resolution-Changer-inator (it looks like a bow tie) that forces people to change their New Year’s resolutions to following him blindly and obeying his every command. (The scheme backfires for the simple reason that people never keep their New Year’s resolutions.) A parody of “Gangnam Style” in the episode’s musical number indicates that it aired around New Year’s Eve 2012.

I look forward to revisiting — maybe not next week, but eventually — Betty Boop’s great party trilogy of 1932. No one could party like the queen of the animated screen!

Bugs also sends Sam into a far-less fun party setting in “Hare Trigger” when the saloon dancing he sees the first time he look into the club car has turned into a bar fight that Bugs lets Sam run right into.

The end part of “You Don’t Know What Your Doin'” with the drunk celebration/hallucination has always felt the most similar to east coast style animation of the Harman-Ising shorts, where normally Hugh and Rudy are trying to do Disney knock-offs. Coming as a homage/steal from the Felix short, it’s easy to see why — and in terms of ‘fun’ animation, more stealing from Otto Mesmer and the Fleischers and less stealing from Walt probably wouldn’t have been a bad thing for H&I early 30s cartoons. Also, the part starting at 4:59 with Felix in the car brings into question the claim that Disney was the first to successfully animate speed — the blur lines behind the drunk cat and his jalopy as they zoom past the cop look awfully familiar (i.e. — Hugh and Rudy may not have been the only ones stealing ideas from this cartoon).