Recently, in this space, we observed an unusual phenomenon from the early years of the Disney studio’s daily Mickey Mouse comic strip. For one week in January 1931, the comic strip was devoted to a surprisingly faithful retelling of an animated cartoon: The Picnic. In January 1931 the Mickey Mouse strip was scarcely a year old, and Floyd Gottfredson—already ensconced as the strip’s artist, a role he would continue to occupy for more than four decades—had established his signature vehicle: the adventure serial, an extended continuity that might run for weeks or even months. But for six days that January, Monday through Saturday, he broke that pattern and simply reproduced The Picnic on the comics page, with striking fidelity to the theatrical short.

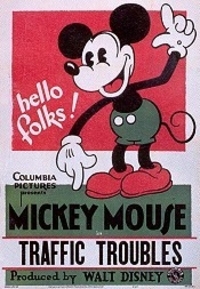

Having essayed this experiment once, Gottfredson returned to it the following week with a second film adaptation. Today we pick up the story with that second one-week continuity, based on Traffic Troubles. This time the animated cartoon and the comics version were produced more or less simultaneously: the comic continuity appeared in newspapers in mid-January, while animation of the film was still in progress. The film was finished shortly afterward and was assigned an official release date in March (see below)—although, in all likelihood, audiences didn’t actually see it until some time later. During the first week in May 1931 it inaugurated what would be a regular Mickey Mouse booking at New York’s prestigious Roxy theater, shown on a program with the Fox feature Three Girls Lost.

CM 11

Released 17 March 1931 by Columbia Pictures

Copyright 20 March 1931 by Walt Disney Productions, Ltd. (MP2393)

Director: Burt Gillett

Animation: • Dave Hand (opening scenes of Mickey in taxi; Mickey has blowout; Pete pours medicine into radiator and taxi runs away)

Animation: • Dave Hand (opening scenes of Mickey in taxi; Mickey has blowout; Pete pours medicine into radiator and taxi runs away)

• Les Clark (pig hails taxi and gets in; Minnie plays accordion while Mickey whistles)

• Tom Palmer (cop bawls Mickey out; taxi bounces off and on chassis; Minnie enters and gets into taxi; Pete’s dialogue)

• Ben Sharpsteen (cop in traffic; Mickey parks and taxi bites other car, Mickey intervenes and discovers missing passenger; Mickey chases taxi, taxi hits rock)

• Dick Lundy (Austin lands on taxi; Mickey tries to fix blowout and replaces broken pump with pig’s snout; car lands on cow’s back)

• Jack King (taxi and Austin in traffic; Minnie plays accordion in CU; inflated tire and pig gag)

• Johnny Cannon (taxi wades through mud and hits bumps; Minnie hails taxi; Pete on bicycle)

• Norm Ferguson (pig inside taxi; taxi tries to dodge bumps; cow runs with taxi on back; crash into barn and gag ending)

• Frenchy de Trémaudan (CU Mickey inside taxi)

Layouts: 29 December 1930–24 January 1931

Animation: 3 January–5 February 1931

The introduction of the automobile at the turn of the twentieth century had revolutionized American society, but it had been a mixed blessing. Vaudeville and silent-film comics had a field day satirizing the unreliability and the foibles of the “horseless carriage,” and in this cartoon Mickey takes up the theme. Traffic Troubles is a fascinating cartoon in several ways, not least because it places Mickey—usually a denizen of the barnyard or the suburbs, during these early years—in an urban setting (at least in the opening scenes). Here, like the live-action comedians, he battles traffic and deals with an officious traffic cop. Minnie’s introduction is similar to that in Steamboat Willie: running along the street with accordion in hand, late for her music lesson, she hails Mickey’s taxi. (En route, she and Mickey break into a duet of a notable tune: “Mickey Mouse (You Cute Little Feller),” published the previous year, one of the first popular songs to celebrate Mickey’s fame.) Peg Leg Pete is on hand, too, demonstrating his acting chops in a highly uncharacteristic role as a snake-oil salesman.

The introduction of the automobile at the turn of the twentieth century had revolutionized American society, but it had been a mixed blessing. Vaudeville and silent-film comics had a field day satirizing the unreliability and the foibles of the “horseless carriage,” and in this cartoon Mickey takes up the theme. Traffic Troubles is a fascinating cartoon in several ways, not least because it places Mickey—usually a denizen of the barnyard or the suburbs, during these early years—in an urban setting (at least in the opening scenes). Here, like the live-action comedians, he battles traffic and deals with an officious traffic cop. Minnie’s introduction is similar to that in Steamboat Willie: running along the street with accordion in hand, late for her music lesson, she hails Mickey’s taxi. (En route, she and Mickey break into a duet of a notable tune: “Mickey Mouse (You Cute Little Feller),” published the previous year, one of the first popular songs to celebrate Mickey’s fame.) Peg Leg Pete is on hand, too, demonstrating his acting chops in a highly uncharacteristic role as a snake-oil salesman.

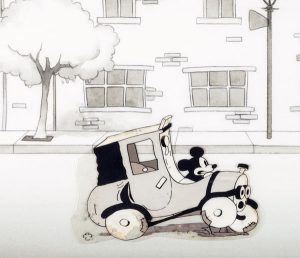

The film’s animation makes for fascinating study. Like that in The Picnic, it displays the individual animators’ distinctive ways of drawing both Mickey and Minnie. (Note Jack King’s striking closeup of Minnie, drawn with his trademark diagonal pie-cuts in her pupils!) In later years, Dave Hand enjoyed telling the story of having to reanimate the taxi’s blowout scene multiple times, trying to exaggerate the explosion further and further until Walt was satisfied with it. Hand’s memory notwithstanding, a viewing of the scene reveals a blowout that seems relatively restrained. He might have added that the same scene includes a modest instance of a moving background—a technical challenge for an animator, and a challenge that Hand himself would tackle on a much more ambitious scale in the later Silly Symphony Egyptian Melodies.

The film’s animation makes for fascinating study. Like that in The Picnic, it displays the individual animators’ distinctive ways of drawing both Mickey and Minnie. (Note Jack King’s striking closeup of Minnie, drawn with his trademark diagonal pie-cuts in her pupils!) In later years, Dave Hand enjoyed telling the story of having to reanimate the taxi’s blowout scene multiple times, trying to exaggerate the explosion further and further until Walt was satisfied with it. Hand’s memory notwithstanding, a viewing of the scene reveals a blowout that seems relatively restrained. He might have added that the same scene includes a modest instance of a moving background—a technical challenge for an animator, and a challenge that Hand himself would tackle on a much more ambitious scale in the later Silly Symphony Egyptian Melodies.

One notable morsel of animation was cut from the film. Norm Ferguson, one of the studio’s top artists, had several scenes in Traffic Troubles, including the frenzied closing with the runaway cow. Originally, however, he also animated a short gag sequence in which Mickey, parked next to a fireplug, disguised it as a person to avoid being ticketed by the cop. Studio records suggest that Ferguson completed these scenes late in January 1931, concurrently with some of the other scenes in the picture—but as we see Traffic Troubles today, this entire gag sequence is missing.

As if to herald this coming attraction in movie theaters, the comics adaptation of the short appeared in newspapers in mid-January.

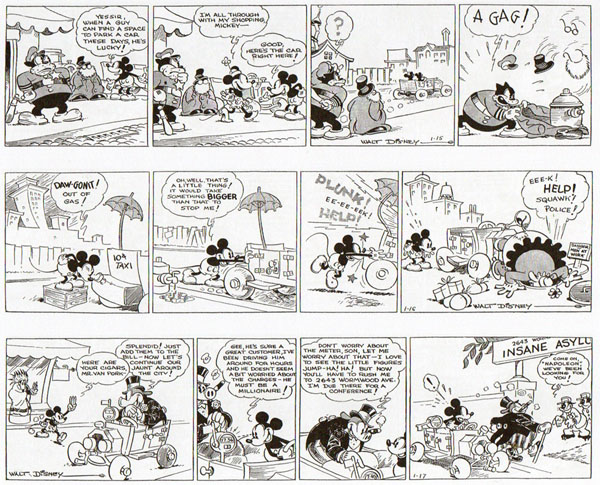

12–17 January 1931, plotted by Floyd Gottfredson, penciled by Earl Duvall (12–15 January) and Floyd Gottfredson (16–17 January), inked by Earl Duvall.

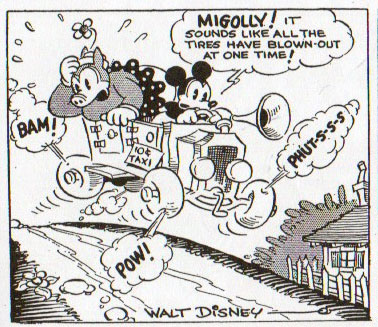

This second one-week comic adaptation differs from the first in one important way. We saw in the previous installment that most of the gags in The Picnic were taken directly from the film of the same name, with only minor variations. Traffic Troubles takes the opposite tack: none of the gags in the film reappear in the strip. Instead the strip borrows the film’s basic setting and situation, then spins new gags from them. The film, for example, makes much of the large, imposing pig whose bulk is too much for the taxi to handle. Here that character morphs into two different characters, and each of them has fresh story material.

Perhaps most interesting is the strip for Thursday, 15 January. We’ve already observed the fireplug gag, animated by Norm Ferguson for Traffic Troubles but eliminated from the final cut. Now the comic strip, published in newspapers while the film is still in production, reproduces the same gag! In the absence of corroborating documentation, we can only speculate whether the film and the comic continuity were deliberately coordinated to avoid duplicating gags.

Perhaps most interesting is the strip for Thursday, 15 January. We’ve already observed the fireplug gag, animated by Norm Ferguson for Traffic Troubles but eliminated from the final cut. Now the comic strip, published in newspapers while the film is still in production, reproduces the same gag! In the absence of corroborating documentation, we can only speculate whether the film and the comic continuity were deliberately coordinated to avoid duplicating gags.

For two weeks in a row, the daily Mickey Mouse comic strip had offered miniature one-week narratives loosely replicating current theatrical cartoons. Today, of course, we know that this would not become the long-term model for the Mickey Mouse strip. Directly following Traffic Troubles, on Monday, 19 January 1931, Mickey would be introduced to a new adversary, Kat Nipp, who had no counterpart on the screen. The ensuing story would extend into late February, and would be followed by an even longer continuity in which Mickey became a boxer. The self-contained adaptations of The Picnic and Traffic Troubles would remain an isolated anomaly in the strip’s history.

This makes sense, of course, for more reasons than one. Not only did Floyd Gottfredson, the strip’s principal writer and artist, have a preference for extended adventure serials, but these linked movie and comic narratives were not a practically sustainable model. The making of an animated cartoon, by the Disney studio’s increasingly painstaking methods, was a process that might take weeks or months. The studio released a total of twelve Mickey Mouse shorts in 1931—and that was an unusually productive year. Gottfredson, obliged to deliver six new comic strips per week, 52 weeks per year, would quickly have run out of material if this format had continued indefinitely.

This makes sense, of course, for more reasons than one. Not only did Floyd Gottfredson, the strip’s principal writer and artist, have a preference for extended adventure serials, but these linked movie and comic narratives were not a practically sustainable model. The making of an animated cartoon, by the Disney studio’s increasingly painstaking methods, was a process that might take weeks or months. The studio released a total of twelve Mickey Mouse shorts in 1931—and that was an unusually productive year. Gottfredson, obliged to deliver six new comic strips per week, 52 weeks per year, would quickly have run out of material if this format had continued indefinitely.

Still, The Picnic and Traffic Troubles adaptations remain a charming and unusual footnote in the early history of Mickey Mouse. And this was hardly the end of the intersections between movies and comics. As the Mickey strip continued, it would continue to reflect stories, gags and imagery from the theatrical films—if not in precisely the same way. Some of those later reflections would prove particularly notable in themselves, and we’ll explore some of them in later columns.

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

I notice that most of the cars in “Traffic Troubles” have patched tires. This may reflect the poor condition of the roads at this time, full of potholes and the occasional wide crevasse. On the other hand, perhaps the patches were an animation ploy to help give a sense of the wheels turning around. After all, the parked cars don’t have any patches on their tires, and the patches disappear from Mickey’s taxi when it’s stopped and the pig is getting in. Also, in the comic strip Mickey’s taxi has no patches on its tires.

I’m amused at how Pete briefly sprouts a second right foot as he pivots on his prosthesis.

J.B. Kaufman is always a fascinating read.

(Both three-strip segments open to the second set, btw.)

Mr. Kaufman:

I can’t wait until you get to THE MAD DOCTOR (1933). Years ago, I contributed to a anthology book called SCIENCE FICTION AMERICA and did a chapter on the FLASH GORDON serials and also two cartoons representing the good and bad uses of Science: Fleischer’s DANCING ON THE MOON and Disney’s THE MAD DOCTOR. As a big fan of Gottfredson, I – of course – wanted to show some of the differences between the animated cartoon and his newspaper comic strip version, and submitted some examples of the strip panels to emphasize the changes. The book publisher was troubled about using ANY of this material, as Mickey Mouse – despite the copyright status of the animated cartoon and – possibly – the comic strips – is a trademarked character. I’m glad you can reproduce the comic strip panels here!

Worth of mention is that the tune heard in the opening scenes of “Traffic Troubles” is Mel B. Kaufman’s “Taxi” recorded by Joseph C. Smith for Victor (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kK-rUETqAAE), Julius Lenzberg’s Riverside Orchestra for Edison (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lz3wl5wCstU) & more recently, the Peacherine Ragtime Orchestra for their Rivermont album “Step With Pep: The Ragtime and Dance Music of Mel B. Kaufman” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KgMntGJ_AfM).

You can find the sheet music for that tune in IMSLP:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KgMntGJ_AfM

I realized that I repeated the link of the Peacherine Ragtime Orchestra recording of “Taxi”.

Here’s the real IMSLP link of the sheet music of “Taxi” including the stock arrangement made by legendary silent film composer John Stephan Zamecnik/J. S. Zamecnik (likely the same stock used in Joseph C. Smith, Julius Lenzberg & the Peacherine Ragtime Orchestra’s recordings of that Mel B. Kaufman tune):

https://imslp.org/wiki/Taxi_(Kaufman%2C_Mel_B.)