The animation connections – including those personally approved by Walt Disney—are part of what makes the 1934 Laurel and Hardy version of the musical fantasy so unique.

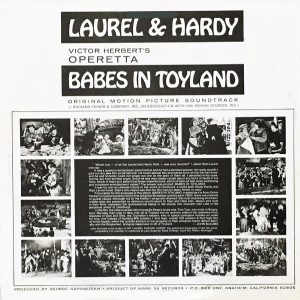

LAUREL AND HARDY in Victor Herbert’s Operetta

BABES IN TOYLAND

Mark 56 Records #577 (12” 33 1/3 rpm / mono)

Released in 1974. Album Producer: George Garabedian. Film Producer: Hal Roach. Screenplay: Frank Butler, Nick Grinde. Directors: Gus Meins, Charles Rogers. Musical Direction: Harry Jackson, John W. Swallow. Running Time: 51 minutes.

Cast: Oliver Hardy (Ollie Dee); Stan Laurel (Stannie Dum); Charlotte Henry (Bo Peep); Henry Brandon (Silas Barnaby); Felix Knight (Tom-Tom); Florence Roberts (Mother Peep); William Burgess (Toymaker); Kewpie Morgan (Old King Cole); Ferdinand Munier (Santa Claus); John George (Barnaby’s Minion); Frank Austin (Justice of the Peace).

Songs: “Castle in Spain,” “Go to Sleep, Slumber Deep” by Victor Herbert, Glen MacDonough.

Instrumental Themes: “Ku Ku (Laurel & Hardy Theme)” by Marvin Hatley; “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf” by Frank Churchill, Ann Ronell; “Toyland,” “Melodramatic,” “Birth of the Butterfly,” “I Can’t Do That Sum,” “Never Mind, Bo Peep,” “In the Toymaker’s Workshop,” “Country Dance,” “Jane,” “The Spider’s Den,” “March of the Toys” by Victor Herbert; “Ducking Scene” by Myrl Alderman.

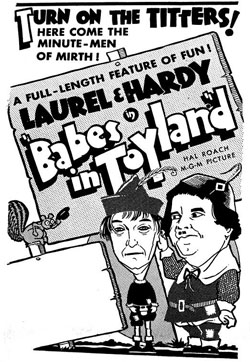

Musical fantasy is notoriously difficult to bring to the movie screen. Mary Poppins was a breezy production, but many were bumpy rides. On first release, some enjoyed varying degrees of success (The Wizard of Oz, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang) or were box office disappointments (Doctor Dolittle), but time has generally been kind to them and each has legions of devoted fans. Many have become so beloved that their initial reception has become obscured by their eventual status.

Both the Hal Roach and Walt Disney versions of Babes in Toyland (the latter of which we explored in this Spin) were bumpy productions. They are frequently compared for reasons of casting, tone and scope, but they actually share lesser-known aspects.

Both the Hal Roach and Walt Disney versions of Babes in Toyland (the latter of which we explored in this Spin) were bumpy productions. They are frequently compared for reasons of casting, tone and scope, but they actually share lesser-known aspects.

The first is the challenge of a cohesive story that would work in a feature film. The original stage operetta of Babes in Toyland premiered in 1903 in Chicago. It traveled to Broadway and became a perennial classic. The musical score was the main reason. Few focused on how it all fits together because shows of this kind—including Toyland’s successful “sister” stage show by the same creative team, The Wizard of Oz–were huge extravaganzas built around lavish musical set pieces, specialty acts and performers. The songs and the plot (such as it was) was written around all the elements).

Toyland’s basic premise involved children in Mother Goose Village and the adjoining Toyland, the scary Spider Forest and the villainous Barnaby. The original Toymaker turned out to be a sorcerer who, conspiring with Barnaby, infused evil spirits into life-size toys so that they could kill children on Christmas Day. (And Tim Burton wasn’t even born yet.)

When the show was revived in 1929, RKO announced the first movie version for the 1930 Christmas season starring Bert Wheeler and Robert Woolsey, two of the biggest comics of the day, as well as Irene Dunne, Ned Sparks and Edna Mae Oliver. According to this fascinating, detailed website devoted to Babes in Toyland history, the Herbert organization changed its mind. There was more to it, according to longtime historian and preservationist Randy Skretvedt’s sumptuously illustrated and exhaustively researched book, Laurel and Hardy: The Magic Behind the Movies. RKO could not get a handle on the story and was ready to abandon the project.

Hal Roach Studios was known as the “Lot of Smiles,” a small, utopian world of great comedians making great silent and then sound short and feature comedies. Roach obtained the rights to Babes in Toyland as his most ambitious production for his biggest stars, Laurel and Hardy. Roach came up with his own storyline with the duo playing Simple Simon and the Pieman. Unfortunately, issues about Roach’s approach to the story ignited a painful series of conflicts between him and Stan Laurel, who was the de facto creative lead of the team (Hardy stayed out of the business and production details and spent a lot of his time on the golf course).

Hal Roach Studios was known as the “Lot of Smiles,” a small, utopian world of great comedians making great silent and then sound short and feature comedies. Roach obtained the rights to Babes in Toyland as his most ambitious production for his biggest stars, Laurel and Hardy. Roach came up with his own storyline with the duo playing Simple Simon and the Pieman. Unfortunately, issues about Roach’s approach to the story ignited a painful series of conflicts between him and Stan Laurel, who was the de facto creative lead of the team (Hardy stayed out of the business and production details and spent a lot of his time on the golf course).

Actors were tested and/or in negotiations for Toyland roles. Charlotte Henry, who had just played the lead in Alice in Wonderland for Paramount, landed the role of Bo-Peep. One of the actors approached was tenor Donald Novis, who performed “Love is a Song” over Walt Disney’s Bambi titles and was one of the stars of Disneyland’s Golden Horseshoe Revue, but negotiations fell through.

The production ground to a halt in 1933 for several reasons, chiefly the divorce of Stan Laurel from his first wife, Lois. He seriously considered going back to England and the trade papers filled with stories of the great team breaking up. Wallace Beery and Raymond Hatton might have replaced them in Babes in Toyland. Patsy Kelly, who later made a number of comedy shorts with Thelma Todd (and Disney fans will know from Disney’s 1977 Freaky Friday) was considered as a comic partner for Oliver Hardy.

“Roach stopped all work on the Toyland script in mid-February, reluctantly deciding to shelve the picture until Stan’s creative, financial and emotional ordeals could be sorted out,” wrote Randy Skretvedt in the aforementioned book. On the 19th, Laurel stated to the press, “I realize my value as a comedian lies in the fact that I am teamed with Hardy.” But within a few weeks, he wrote to a friend, “It is impossible to be funny with a broken heart.”

“Roach stopped all work on the Toyland script in mid-February, reluctantly deciding to shelve the picture until Stan’s creative, financial and emotional ordeals could be sorted out,” wrote Randy Skretvedt in the aforementioned book. On the 19th, Laurel stated to the press, “I realize my value as a comedian lies in the fact that I am teamed with Hardy.” But within a few weeks, he wrote to a friend, “It is impossible to be funny with a broken heart.”

Hardy was having marital problems as well. Both situations eventually led to new relationships all of which are too convoluted for Animation Spin (but are in Skretvedt’s book). Babes in Toyland went back into production with a new script. The team would now take a page from Lewis Carroll and play Ollie Dee and Stannie Dum. “The plot that was eventually used bore little relation to either Victor Herbert’s 1903 production or to Roach’s idea,” wrote Skretvedt.

Animation and special effects figured heavily into Babes in Toyland. Many impressive effects and opticals had already been used in Laurel and Hardy films, from clever title changes and rear-screen sequences to more complex split screen and double-exposures, especially noticeable in such films as Brats, in which the two were seen both as adults and as children. This work fell to the ever-capable hands of Roy Seawright.

Seawright, who started at the Roach studio as an office boy, moved to the prop department and eventually headed special effects. Much overdue attention is afforded to Seawright on the spectacular new Blu-ray set, Laurel and Hardy: The Definitive Collection, which contains pristine selected shorts and features with one or two commentaries per film and many new extras.

“Roy Seawright was a man of many, many talents,” says Skredvedt on the Blu-ray. “He helped devise physical props and he was a talented artist and animator. He also created the matte shots and other optical effects work. For example, there’s a shot in County Hospital where Stan’s Model ‘T’ lifts up when it backfires. In the original shot, evidently you could see a crane lifting it. Film editor Richard Currier told me that he asked Roy, ‘Can you get that crane out of the shot?’ and somehow Roy was able to erase that.” This was almost one hundred years ago, folks.

“Roy Seawright was a man of many, many talents,” says Skredvedt on the Blu-ray. “He helped devise physical props and he was a talented artist and animator. He also created the matte shots and other optical effects work. For example, there’s a shot in County Hospital where Stan’s Model ‘T’ lifts up when it backfires. In the original shot, evidently you could see a crane lifting it. Film editor Richard Currier told me that he asked Roy, ‘Can you get that crane out of the shot?’ and somehow Roy was able to erase that.” This was almost one hundred years ago, folks.

While the animation in King Kong has earned its proper due as a landmark in stop-motion history the toy soldier sequence in Babes in Toyland, though much shorter and less elaborate, is nonetheless worth more attention in its early Hollywood context.

“In the production of Laurel and Hardy comedies, there was an awful lot of really serious thought given to the creation of these effects,” said Seawright (in a 1981 interview by Skretvedt on Super-8 film, which is on the Blu-ray) “On Babes in Toyland, when Stan and ‘Babe’ [Hardy’s childhood nickname] open up the door to the toy factory and you look up the alley into the toy factory and you see all the toy soldiers lined up—well, those toy soldiers were only ten inches high, and it was my job to make a traveling matte that, when they opened the doors on to a brick wall, you looked into a miniature set which we concocted on an old handball court. It was a court that we used to play squash and handball on that we converted for stop-motion and trick work.

“The soldiers were all made of ball-and-socket… there must have been eighty of them in the group… Every one of them had big lead feet and so forth and they had to be moved about a quarter of an inch to the frame… It took us two weeks to shoot the one scene from different camera angles—low shots looking up, cross angles, long shots and so forth of these wooden soldiers. They came out the door and walked right past the camera. Then they swung to the live-action, the actors with the costumes on them…

“To me, it was a big challenge. In those days, back in the ‘20s and ‘30s, we were working with the typical ‘spit and baling wire and cotton,’ you know, and tape. We didn’t have the stop-motion equipment or the technique or even the knowledge to do these effects.

In addition to the toy soldier sequence, the main title opening contains tabletop photography of alphabet blocks to spell out the title, followed by the entrance of Mother Goose to sing “Toyland” as she appears to turn the giant storybook pages. Each page is a cutaway viewing featuring various characters, ending on a composite of shots zooming inside the book to Toyland, which combines the gigantic set with a matte painting.

The Toyland stage was the most elaborate set ever constructed on the Roach lot. Despite the black and white photography, the art direction was in full color. All the costumes and set pieces were also rendered in color. According to the album notes by John McCabe, Laurel himself regretted that the production was not filmed in color. Therefore, a case can be made that this film is perhaps the only one to be colorized, based on the original intent and because the overall artificiality of the settings lends itself to the limits of digital coloring. There have been two colorized editions released several years apart and the 2006 Legend Films release benefits the most to date from the advances in the technology.

The other animation links in this journey through Toyland are fascinating and a bit strange to some viewers. Walt Disney was a good friend to Hal Roach and gave his personal approval for the appearances of Mickey Mouse and the Three Little Pigs (the hit Silly Symphony cartoon had only been in theaters for just a year and was at the peak of its phenomenon status).

In his book, Skretvedt quotes a letter from Walt Disney to Hal Roach from July 27th, 1934: “You may use any piece of the sound track, as well as any models of the characters. In other words, we are more than glad to cooperate with you in every way.”

Walt even offered the original voice actors for the pigs, but that was not deemed necessary. Their names were also changed for this film, but the megahit “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” plays several times in the film, the equivalent of adding a pop hit to a family film today. (It is also notable that frequent Roach studio player Billy Bletcher appeared in Babes in Toyland and was the voice of the Big Bad Wolf as well as Pete and other Disney characters.)

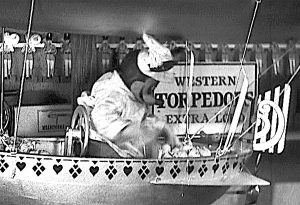

“Mickey” is first seen throwing a brick at The Cat and the Fiddle—a nod to Ignatz the mouse from the popular “Krazy Kat” comic strip (Skretvedt speculates that the monkey playing Mickey may have been a capuchin named Josephine, owned by Tony Campanaro, the Roach studio animal trainer). Mickey takes an active role during the final battle scene, when he boards a toy blimp, fills it with toy torpedoes and drops them on the horrible bogeymen. The 1961 Disney Toyland film also has a toy blimp in its soldier sequence, without Mickey or any torpedoes.

“Mickey” is first seen throwing a brick at The Cat and the Fiddle—a nod to Ignatz the mouse from the popular “Krazy Kat” comic strip (Skretvedt speculates that the monkey playing Mickey may have been a capuchin named Josephine, owned by Tony Campanaro, the Roach studio animal trainer). Mickey takes an active role during the final battle scene, when he boards a toy blimp, fills it with toy torpedoes and drops them on the horrible bogeymen. The 1961 Disney Toyland film also has a toy blimp in its soldier sequence, without Mickey or any torpedoes.

Roach never again produced a feature so extravagant. The film was fraught with difficulties, including injuries on the set (someone even fell off the shoe that the old woman lived in). There were off-screen hospital stays and much bickering between Laurel and Roach that affected their friendship. While Laurel and Hardy later expressed affection for Babes in Toyland, Roach did not. He was not pleased with the film, perhaps because of the experience, and insisted it was not a success. In reality, it opened to generally excellent reviews and strong box office. But the huge expense outweighed the profits, especially when compared to other Laurel and Hardy features.

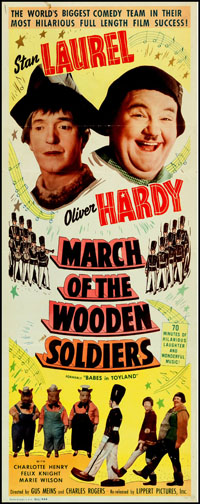

False (and often malicious) information has circulated for years that Walt Disney forced the 1934 film’s title to change from Babes in Toyland to March of the Wooden Soldiers to prevent competition with his 1961 musical. As mentioned, he and Roach were good friends and Roach was still alive. The fact is that Roach only retained a ten-year distribution on his Toyland. The Victor Herbert estate did not allow the next distributor to use the title (the property was still very popular) or the “Toyland” song. The beginning section was removed and it was retitled March of the Wooden Soldiers in 1950 for television. At one time it was given the title Revenge is Sweet.

False (and often malicious) information has circulated for years that Walt Disney forced the 1934 film’s title to change from Babes in Toyland to March of the Wooden Soldiers to prevent competition with his 1961 musical. As mentioned, he and Roach were good friends and Roach was still alive. The fact is that Roach only retained a ten-year distribution on his Toyland. The Victor Herbert estate did not allow the next distributor to use the title (the property was still very popular) or the “Toyland” song. The beginning section was removed and it was retitled March of the Wooden Soldiers in 1950 for television. At one time it was given the title Revenge is Sweet.

The constant TV airings under the revised title led many to believe that “March” was the correct title; the video releases also used “March” as the lead title and “Babes” as the subtitle because so many knew it from TV. However, the correct title seems to be returning, with the TCM doing its part by listing it as Babes in Toyland as the cable channel celebrates a month-long Laurel and Hardy salute. [It will be broadcast on TCM this Friday, Christmas day.)

While there were several recordings of the Babes in Toyland songs, including a few produced by Herbert’s own orchestra, there was no soundtrack album for the Laurel and Hardy feature. No soundtrack records were ever issued for their films during the original release dates. It wasn’t until the 1970’s when independent record companies began to license them in the U.S. and Europe. By then the separate mix elements were gone, so all that remains are finished film tracks with all the sound effects and dialogue.

Mark 56 Records was one of these small companies. “George Garabedian, whose real first name was evidently Marcus, started Mark 56 Records in November 1958,” Randy Skretvedt tells us for this article. “A lot of his first releases were vanity projects featuring himself as orchestra leader (and possibly singer). I became aware of the label as a kid in the early ’60s because it was based in Anaheim, which is right next door to my home town of Buena Park. Many of his early LPs were sponsored items, with a company getting a plug on the jacket artwork, presumably for having helped to finance the project. This practice continued into at least the ’70s, with Coca-Cola sponsoring an album of W.C. Fields radio excerpts, and Frigidaire prominently advertised on a Lum and Abner radio show LP.

“Garabedian made a deal with Richard Feiner to do a series of Laurel & Hardy soundtrack LPs in 1973, which is when the first album was issued. It was originally a picture disc, although a later pressing was on standard black vinyl.”

The albums were —

575 Laurel & Hardy Original Motion Picture Soundtracks

577 Babes in Toyland

579 Another Fine Mess

600 In Trouble Again!

601 No U Turn

688 Way Out West

689 Sons of the Desert.

The Mark 56 soundtrack album edits the entire 77-minute running time to 51 minutes. The main title is shortened, the songs “Toyland” and “Bo-Peep” are omitted and the visual portions of comedic scenes are trimmed. The dialogue and music that remains is an audio delight, working well as pure audio, even if the listener has never seen the film.

Listening draws attention to the musical entertainment timeline in which this film fits in relation to Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and The Wizard of Oz (1939). All were released within mere years of each other, yet they offer a notable transition from the operetta style of musical presentations to the eventual “book” form of musical theater later brought to the fore with Oklahoma!

The “Ducking Pond” Scene

Even without the picture, this sequence plays quite well in audio. It’s hard to imagine in retrospect that Laurel and Hardy were apprehensive about whether the advent of sound would destroy their careers, as it had done with other stars. Sound only made them better and records bring this home.

In addition to Randy Skretvedt, the author gratefully thanks Richard W. Bann and Ray Faiola for their years of devoted Laurel and Hardy research work, which was indispensable in making this article possible. Bann is also featured on the special features of the Blu-ray, Laurel and Hardy: The Definitive Collection.

LAUREL AND HARDY in Victor Herbert’s Operetta

BABES IN TOYLAND

The Sound Track Factory SFCD-33546 (Compact Disc / Mono)

CD Reissue: Calle Mayor (Spain) ST-0027 (2017) (Toyland tracks only)

Released in 2000. Album Producer/Editor: J.G. Calvados. Running Times: 37 minutes (“Toyland” tracks) ; 28 minutes (additional tracks); 65 minutes (total).

Performers: Oliver Hardy (Ollie Dee); Stan Laurel (Stannie Dum); Virginia Karns (Mother Goose); Charlotte Henry (Bo Peep); Henry Brandon (Silas Barnaby); Felix Knight (Tom-Tom); Florence Roberts (Mother Peep); Billy Bletcher (Chief of Police); Alice Dahl (Little Miss Muffet); Sumner Getchell (Simple Simon); Fred Holmes (Balloon Man); William Burgess (Toymaker); Johnny Downs (Little Boy Blue), Jean Darling (Curly Locks); Ferdinand Munier (Santa Claus).

Babes in Toyland Songs:

“Toyland,” “Bo-Peep,” “Castle in Spain,” “Go to Sleep, Slumber Deep” by Victor Herbert, Glen MacDonough.

“Toyland” Instrumental Themes (with Dialogue): “Toyland,” “March of the Toys,” “Jane,” “Melodramatic,” “Birth of the Butterfly,” “I Can’t Do That Sum,” “Never Mind, Bo Peep,” “In the Toymaker’s Workshop,” “Country Dance,” “The Spider’s Den,” by Victor Herbert; “Dance of the Cuckoos” (Laurel and Hardy Theme) by Marvin Hatley; “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf” by Frank Churchill, Ann Ronell; “Ducking Scene” by Myrl Alderman.

(CD dialogue tracks that include the above themes: “Good Morning Everybody,” “Good Morning Old Master,” “Jour de fête at Toyland,” “The Christmas Surprise,” “The Bogeymen attack Toyland.”)

Additional Laurel and Hardy Songs:

• “The Trail of the Lonesome Pine” (Ballard MacDonald / Harry Carroll) from Way Out West – • The Avalon Boys, Oliver Hardy & Rosina Lawrence

• “At The Ball, That’s All” (J. Heubrie Hill) from Way Out West – The Avalon Boys

• “I Want To Be In Dixie” (Irving Berlin/Ted Snyder) from Way Out West – Stan Laurel, Oliver Hardy & Rosina Lawrence

• “In The Good Old Summertime” (George Evans/Ren Shields) from Below Zero – Oliver Hardy

• “Lazy Moon” (J. Rosamond Johnson / Bob Cole) from Pardon Us – Oliver Hardy

• “Fresh Fish” (Oliver Hardy / Leroy Shield) from Towed in a Hole – Oliver Hardy

• “We Are the Sons of the Desert” / “Honolulu Baby” (Marvin Hatley) from Sons of the Desert – Ty Parvis

• “Let Me Call You Sweetheart” (Leo Friedman/Beth Slater Wilson) (and another theme) – Oliver Hardy

Additional Laurel and Hardy Instrumental Themes (with Dialogue):

• “The Cuckoo Song” (“The Dance of the Cuckoos” Laurel & Hardy Theme) (Marvin Hatley)

• “Stagecoach Manners” from Way Out West (Marvin Hatley) Dialogue with Score

• “When the Mice Are Away” from Helpmates (Themes by Hatley & Shield)

• Main Title from Sons of the Desert (Hatley)

• “Turn On the Radio (Smile When the Raindrops Fall)” (Alice K. Howlett) from Busy Bodies

• “Furniture Payment” (Themes by Hatley & Shield)

• “The Dance of the Cuckoos” (Marvin Hatley) Columbia Records, Arranged by Van Phillips, London, 1932

While not a complete dialogue and story album like the the Mark 56 soundtrack, this CD draws mostly the musical highlights from the same finished film track, but adds more musical material that the LP omitted for space, particularly (most of) the opening, “Toyland” and “Bo-Peep.”

To round out the program and make it play longer, the first issue of this disc also includes a “best of” program with many of the most memorable songs, musical cues and comedy bits from years of Laurel and Hardy films. The CD reissue does not include this extra material.

The Laurel and Hardy films are so rich in visuals—just their facial expressions alone—that sometimes the immense variety and quality of the other audio elements can be overlooked. Having a nice buffet table filled with these treats is a feast indeed.

“Trail of the Lonesome Pine” from Way Out West

Vintage films and cartoons enjoyed new popularity in the seventies. In 1975, a newly issued vinyl recording of this song from Laurel and Hardy’s classic feature Way Out West became such a big hit in England it was the number two song on the popular music charts, with Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” at number one. The soprano is Rosina Lawrence, who plays Mary Roberts in the film; she was also Miss Jones, the schoolteacher in several Our Gang films.

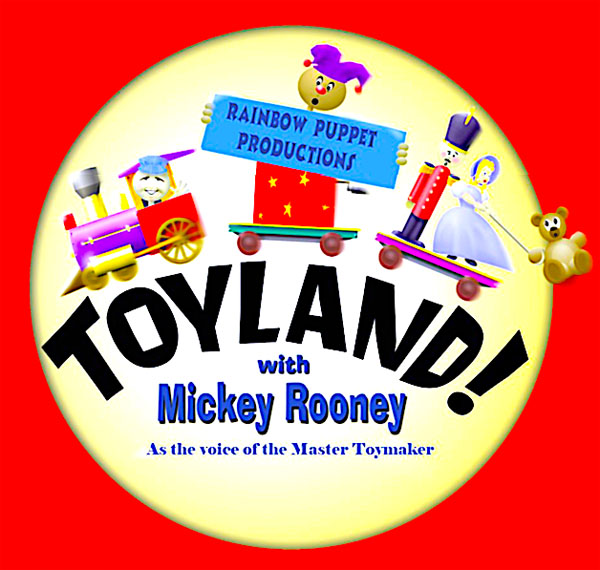

Rainbow Puppet Productions Presents

TOYLAND!

With Mickey Rooney as The Master Toymaker

Original Cast Album

Rainbow Puppet Productions [no catalog number] (Compact Disc / Stereo).

Released in 2005. Album Producer/Engineer: Steve Scheffler. Adaptation: David Messick, from the Operetta by Victor Herbert and Glen MacDonough. Album Producer/Editor: J.G. Calvados. Running Times: 49 minutes.

Performers: Mickey Rooney (The Master Toymaker); Jan Rooney (Mother Goose, Fairy Princess); Steve Scheffler (Barnaby); Jim Stesvaag (Tom/Floretta); Kara Dennison (Little Bo Peep); David Messick (Grumio); Cindy Kaye (Red Riding Hood); Don Bartlett (Big Bad Wolf); Tim Therrington (Jack); Lisa Ryan (Jill); Chris Bartlett (Woman Who Lives in a Shoe); Tiffany Hess (Miss Muffett); Craig T. Adams (Gonzorgo); Jason Wiedel (Rodrigo, Conductor); Beverley Slayton (The Cypress Tree); Tyler Ryan (Atmosphere).

Songs: “Here in Mother Goose Village,” “Don’t Cry, Bo Peep,” “I Won’t Be Happy (Till I Get It).” “Floretta the Gypsy,” “Go to Sleep,” “Here in Toyland,” “The Candy Song,” “Toyland,” “I Can’t Do the Sum,” by David Messick, adapted from Victor Herbert melodies and Glen MacDonough lyrics.

Instrumentals: “March of the Toys,” “The Spider Attack,” “The Russian Toys,” “The Dancing Bears,” “The Irish Dancers” by David Messick, adapted from Victor Herbert melodies.

Rainbow Puppet Productions founder David Messick, Mickey Rooney, Jan Rooney and puppet performer Craig T. Adams after a recording session.

Since Mickey Rooney was at the center of the Rankin/Bass classic Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town, which we discussed in this recent Spin, it seemed fitting to mention the time he ventured into Toyland.

Based in Virginia, Rainbow Puppet Productions was established in 1977 by David Messick. A non-profit entertainment and educational organization, the troupe performs in theaters and schools in several original musicals, many featuring the voices of legendary stars including Carol Channing and Mickey Rooney, who with his last wife Jan was heard in several of their shows.

For Toyland! Rooney voices a benevolent Toymaker in a story that uses some of the original tunes but adds new lyrics to other Herbert melodies. It was introduced in 2003 to celebrate the Centennial of the premiere of the original stage operetta. Many of the Rainbow Puppet Productions shows were recorded on CDs and for downloads and are currently available on Amazon and other platforms. More information about is on their website.

Because the story is so loose, there is no end to the ways Babes in Toyland can be adapted for almost any entertainment medium. There was a live stage musical presented at Dolly Parton’s Dollywood theme park, an excellent LP from Golden Records narrated by character actor George Voskovec; a musical story version with the Herbert songs on MGM children’s records; another story record from Pickwick featuring some original songs James Dukas (Count Chocula) as Barnaby; and even a kooky disco version in the mid-seventies called “The Babes in Toyland” that had a Krofft vibe. The Chicago Theater of the Air musical radio dramatization can be heard here.

Mickey Rooney’s 90th Birthday Salute

The cast and staff of Rainbow Puppet Productions put together this special presentation, with an original song, saluting their most prolific star on his 90th birthday.

GREG EHRBAR is a freelance writer/producer for television, advertising, books, theme parks and stage. Greg has worked on content for such studios as Disney, Warner and Universal, with some of Hollywood’s biggest stars. His numerous books include Mouse Tracks: The Story of Walt Disney Records (with Tim Hollis). Visit

GREG EHRBAR is a freelance writer/producer for television, advertising, books, theme parks and stage. Greg has worked on content for such studios as Disney, Warner and Universal, with some of Hollywood’s biggest stars. His numerous books include Mouse Tracks: The Story of Walt Disney Records (with Tim Hollis). Visit

Thanks for providing a link to that Babes in Toyland site. I can see I’ll be spending some time visiting there over the Holidays.

Laurel and Hardy did end up playing Simple Simon and the Pieman (sort of) in the Silly Symphony short “Mother Goose Goes Hollywood.” Perhaps Disney knew of the earlier “Babes in Toyland” draft, but most likely it was just a case of great minds thinking alike.

One thing I especially like about the Laurel & Hardy version of “Babes in Toyland” is that in this production they are part of a community. Much of their comedy in other films seems to be isolated–while there are other people around, the focus is always exclusively on Laurel & Hardy and their antics. In “Toyland” it is more of an ensemble effort, and Ollie Dee and Stannie Dum have a genuine rapport with the Woman in the Shoe and Bo Peep. Also, others occasionally take center stage, including Mickey Mouse and the Three Little Pigs, or Bo Peep and Tom Tom, and this likewise contributes to a sense of community in the Mother Goose Village. The audio clip used above drives this point home, as the rest of the villagers are witness to the ducking scene and the reactions of the crowd play an important role.

Walt Disney was certainly generous with Mickey Mouse in those early years. Not only did he give permission for his characters to appear in “Toyland,” he also loaned Mickey to MGM for “Hollywood Party” in that same year, as well as providing an animated sequence in the style of the Silly Symphonies for that film as well. (And coincidentally or maybe not, Laurel & Hardy were featured players in the film.) Later on, the Disney studios maintained a much tighter grip on their copyrighted properties. By the time of “Anchors Aweigh” in the mid-40’s, Disney refused to loan Mickey Mouse to MGM for Gene Kelly’s dance sequence, and Jerry the Mouse, already an MGM property, had to be brought into service instead. It certainly marks a change in corporate attitude–although the resulting animated dance sequence turned out spectacularly well, in any event.

“Babes in Toyland” is definitely great holiday entertainment. So far this season I have watched both the 1934 and the 1961 versions, and don’t ask me to decide which one I liked best. Each one has its own pluses. And each reflects the aesthetics of the time period when it was made. And both have the benefit of a touch of Disney magic!

Outstanding article packed to the brim with information I never knew. Besides Walt Disney being friends with Hal Roach, he was also good friends with Laurel and Hardy which might also have influenced his decision to loan Mickey and the Pigs to the Roach production. I am curious why those three names were chosen for the pigs but probably just another mystery lost to time.

Supposedly Walter Lantz animated a short segment in a Laurel and Hardy movie where they were dreaming of flying elephants. And wasn’t there a Laurel and Hardy film that ended with one of them as a horse and they had asked Disney to do the animation but he turned them down? Or am I misremembering?

Was excited to see the mention of George Garabedian since I bought many records produced by him connected to Old Time Radio and one of my treasures is the Original Soundtracks to the Laurel and Hardy Films. Several friends told me to throw away my vinyl collection because everything would eventually be on CDs and thankfully I didn’t since I don’t think any of Garabedian’s productions ever made the transition.

I agree that the trained monkey was probably a capuchin since they are among the most intelligent of monkeys and are still used today in film franchises like Pirates of the Caribbean and Night at he Museum.

The film was reviewed in THE NEW YORK TIMES on December 13, 1934 where Mickey Mouse was mentioned as part of the cast. By the way, the cat that Mickey throws the brick at is actor Pete Gordon in a costume.

Walt had earlier “loaned” Mickey out to Douglas Fairbanks for the United Artists travelogue Around the World in 80 Minutes where an animated Mickey does a thirty second cameo dancing to Siamese music. Mickey Mouse was so popular in the 1930s that excerpts from Mickey Mouse cartoons appeared in movies from other studios. A short clip from Mickey Mouse’s “Ye Olden Days” (1933) is seen at the beginning of the Fox Films, “My Lips Betray” (1933). Republic Pictures Corporation film “Michael O’Halloran” (1937) features an excerpt from “Puppy Love” (1933). In the famous Paramount’s “Sullivan’s Travels” (1941) is an excerpt from “Playful Pluto” (1934) that convinces Joel McCrea’s character of the importance of laughter during the Great Depression.

Thanks for your kind words, Jim (and everyone else too.) And thanks for all the added history! Lots of love went into the labor of these Toyland posts.

Everyone should watch Sullivan’s Travels on a regular basis because it drives such a powerful message home and uses a Pluto cartoon to do it.

Capra’s Meet John Doe is also a powerful and highly relevant film. Not only that, but the song “Hi-Diddle-Dee-Dee (An Actor’s Life for Me)” from Pinocchio figures into it.

Thanks for your excellent article, Greg. I’m glad I was able to contribute something to it. I’m working on a book about the many incarnations of “Babes in Toyland” from 1903 to recent projects, but highlighting the L&H film. You provide some interesting ideas which I will likely steal, er, adapt into the book…..

Best wishes for a new and improved 2021

–Randy

I have a lovely version aimed at families (particularly children) that played in Avery Fisher Hall 4 separate years with The Little Orchestra Society of New York (full orchestra). It will be lengthened and play again produced by the Victor Herbert Renaissance Project LIVE! sometime in the next two years.

Another Disney connection: One of the boys in “Babes in Toyland” is Dickie Jones, who later did the voice of Pinocchio. You can see Dickie very plainly in the climactic battle scene, clinging to the leg of a wooden soldier.

Thanks. We had a great time working with Mickey on seven shows. Toyland! was the first. Randy… we started presenting Toyland in the 1970’s and toured with productions featuring as many as 100 performers. The 100th anniversary production was the one with Mickey. We still tour with that one to this day. It features music from the original but has a tighter, new script and new lyrics to much of the music.

If you read Richard Barrios’ book “A Song in the Dark,” you get a strong flavour of what things were like in the latter half of 1930/first half of 1931; musical films were doing very, very poorly at the box office for a wide variety of reasons. RKO had only dipped its toes into the genre, and in general had done only fair-to-middling (“Dixiana,” “Check and Double Check,” “Hit the Deck”). Any chance to bail out of a what looked like a sure loser would have been taken, the more so since other investments were being made by RKO — including a stake in the Van Buren studio.

One more Disney lend-out: Alfred Hitchcock’s 1936 “Sabotage” had “Who Killed Cock Robin?” playing in a cinema during a tense scene. There’s a thank-you to Walt Disney in the opening credits. One wonders if Walt saw how it was used — the film is dark, even for Hitchcock.

I’d guess in those early years the Disneys welcomed invitations to sit at the big feature table. Perhaps the characters in “Babes in Toyland” were a free favor to Hal Roach, but did they collect a fee when clips were used as in “Sullivan’s Travels”? They certainly must have been paid for new animation, as in “Hollywood Party”. When he was dealing with a studio other than his current distributor, did that figure in the deal? United Artists execs may well have been peeved when Mickey was featured prominently among MGM stars in advertising for “Hollywood Party” (which bombed, by the way).

I’m guessing Walt Disney got much pickier when his own studio was better established. One, he no longer craved the presumed prestige of Mickey & others being allowed in somebody else’s show; if anything they now would be money in somebody else’s bank. That was already a fact of life with Disney shorts being used to sell bookings and draw audiences for lackluster features, and still getting the smallest cut of the box office.

There is probably truth to each of the theories as to why Walt Disney was generous with the lending of “intellectual property” in the thirties than he was in the forties. I use that “I.P.” phrase because it did not exist for decades in the days of Babes in Toyland or Hollywood Party, where deals were less formal and the movie business was still fairly young. Today’s use of the phrase exemplifies how complicated such arrangements have become.

My theory is that it was a direct result of the vastly different places Walt Disney, his studio, Hollywood and the world between Toyland and Anchors Aweigh in 1945.

In 1934, Walt Disney was a young, rakish fellow who played polo with Hal Roach. Mickey Mouse had become an international phenomenon over the previous five years, Silly Symphonies were going strong and Three Little Pigs had not only scored at the box office but also given the studio its first pop song. Lending Mickey and the three pigs to another, friendly production was cross-promotion for Disney, but more than that, it was establishing these characters as celebrities and the publicity was, as you stated DBenson, validating.

But Walt had not yet made a feature, nor ventured into live-action. This was before the war and the strike. MGM had not yet made The Wizard of Oz, which was in response to Snow White, as was Gulliver’s Travels. Things were getting competitive.

The clips for the later films might have been lent for a fee or barter, but it could have depended on who was asking. Hitchcock was so renowned it must have been a huge compliment to have him ask for an excerpt. I can’t believe that Walt Disney did not know how it was going to be used. He had not yet completely established his “brand” with “Sabotage” was made in 1936, so it must not have mattered at the time.

Having a clip in a Preston Sturges movie for a still-fledgling studio like Disney, I agree again, was a major status symbol for Disney in 1941. After all, Paramount could have used a Popeye clip.

The Terrytoons cartoon “Toyland”, released just before Christmas in 1932, seems to have been inspired by “Babes in Toyland”. Santa Claus drops a parcel down a chimney, which emerges from the fireplace below to disgorge a squadron of six wooden soldiers. They are followed by a parade of nursery rhyme characters, including Jack and Jill, Simple Simon, Mary Quite Contrary, Little Bo Peep and Little Boy Blue — all of whom are characters in the Victor Herbert operetta. The three other characters in the parade are:

1) Little Jack Horner, corresponding to Peter Peter Pumpkin Eater, who in the operetta is devoted to eating pie, like Jack;

2) Puss in Boots, who has an analogue in the Hal Roach movie, though the cat does not wear boots (but plays the cello left-handed); and

3) Humpty Dumpty, who seems to presage the incorporation of characters from Lewis Carroll’s “Through the Looking Glass”, namely Dee and Dum.

The music in the cartoon is not taken from the operetta but is strongly reminiscent of it. Perhaps, when RKO abandoned its film version of “Babes in Toyland”, Terry figured the story was up for grabs. Or maybe he or his story men just happened to catch the Broadway show during its 1929 or 1930 revivals. In any case, the cartoon is an interesting precursor to the Hal Roach film that was released two years later.

Have a holly jolly Stan and Ollie Christmas, everybody!

Jim–Walter Lantz worked as a gag writer and animator on “Flying Elephants,” a 1928 comedy starring Laurel and Hardy as cavemen. They weren’t really a team yet, just two comedians who happened to be in the same movie; they don’t appear together until the final few minutes. At one point Ollie says “Beautiful weather–the elephants are flying south,” and we see some cartoon elephants doing just that.

The film is on YouTube, if you want to see Laurel and Hardy before they were “Laurel & Hardy.”

Great article Greg! Here’s a funny story about the Mark 56LP. When I first got it upon release, I thought there was a skip in the record at the beginning when it cuts from the Roaring Lion to the end of the Cuckoo song. I tried and I tried to hold back my needle to get the entire cue to play properly! Hah! Of course I ruined the disc and had to replace it. Fast forward to 1990 when, on behalf of CBS/Fox (I was an exec at CBS Network) I started searching for the uncut version of the film. My first call was to Dick Feiner. I asked where the 35 was that Garabedian had used for his LP. Feiner had no idea! Thus the long search ensued, finally winding up at Eastman House. BTW – here’s a link to my TOYLAND tribute page: http://www.chelsearialtostudios.com/toyland/toyland.htm

Thank you, Ray. Your site is excellent, and so is the radio interview that is included. I thought the record skipped during the part when the Toymaker was yelling at “the boys,” but it’s just an awkward edit. Funny story: many years ago, I had a poorly pressed copy of this that I was trying to return to the store. The clerk didn’t believe me because he was too ignorant to understand what I was talking about. So right there, in the middle of this very hip, rock-oriented store, where Meat Loaf and Peter Frampton was usually played, comes Felix Knight singing “Castle in Spain” as all the other customers turned their heads and tilted them sideways like puppies. Such is the life of a collector who spins to a different drummer.

Randy — high praise coming from an expert like you in an area in which I am only dabbling. I’ve been watching the Laurel and Hardy films during December on TCM (again) and reading about each one in your book and the histories are spectacularly detailed. The “Stan and Ollie” movie only scratched the surface of the backstage drama as well as the joy (which I wish that film had in a little larger measure). Please let me know if I can be of any assistance with your Toyland book as far as recordings research.

Love both these two knuckleheads and Mickey Mouse. Thanks!