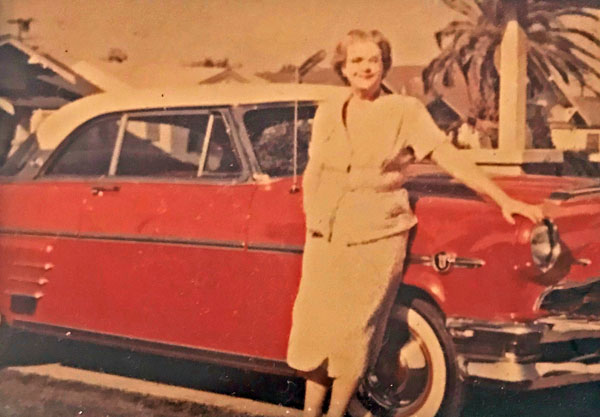

A real joy of having my columns on Cartoon Research has been getting calls out of the blue from families of animators I’ve written about. And one of those inquiries came recently from Judy Usik, a niece of La Verne Harding. This helped fill a gap in what’s known about Ms. Harding, an important figure from the Lantz studio who drove around Hollywood in style. In fact, her ’54 red Mercury may have zoomed through a classic cartoon. With my chance to meet Judy and her family, here are some colorful new anecdotes that I can share with you about their amazing Aunt Verne.

LaVerne Harding and her 1954 Mercury

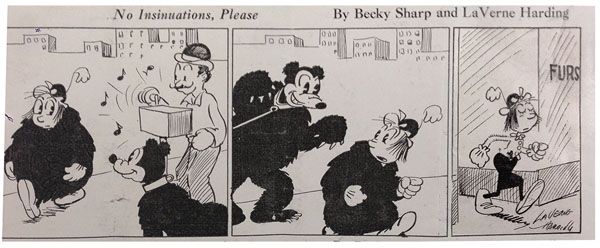

To give a quick recap of my earlier posts, Harding was the first female animator in Hollywood, the co-creator of the Cynical Susie comic strip, a pivotal advocate for Walter Lantz taking his studio independent, and she exerted a strong design influence on his characters, including Woody Woodpecker. After a career that spanned more than four decades, her peers honored her with the Winsor McCay Award in a ceremony that also saw the induction of Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston. She came out of the evening as a certified legend.

Harding’s talent and focus made her an indispensable animator for many years at Lantz. She was never a prankster like others, a role she gladly left to “the boys” all around her, but she was amused by the lengths they would go to pull off a gag. There was that time they bought several pairs of shoes in descending sizes. One of the animators liked to work with his shoes off, so naturally they replaced them when he wasn’t looking, taking them down by a half-size each day until he was distraught how tight they’d gotten, rubbing his sore feet as the others chuckled.

This was the freewheeling state of the midcentury studio, replete with spitballs, traps, and switcheroos. I’ve had the sense that La Verne was serious about being funny, that she channeled her mischief through characters and animation, but I learned she was a spark plug herself, a storyteller who could command an audience. That’s the Aunt Verne that her nieces remember. It’s an open secret in the family that she gave Tex Avery the idea for Crazy Mixed-Up Pup. She received top credit in that cartoon for her animation and it’s worth considering now if she gets a posthumous asterisk from film historians.

Harding liked to call herself the “happy spinster” and she had three little ones whom she doted on. These were her nieces and nephew, Judy, Marlene, and Jon, who all grew up around Los Angeles. Judy informs me that La Verne was “the coolest aunt in the world” and Marlene describes her as “even better than the best aunt ever.” The stories they shared with me give a more complete portrait of this trailblazing animator. She loved baseball, westerns, Hawaiian music, gadgets, and big vehicles. She was born Emily La Verne Harding in Shreveport, Louisiana and she was a Southern girl whose family moved West when she was young.

La Verne Harding, left, with her Shreveport cousins in the early 1910s.

It did not strike her as historic when she became an animator in 1934 while working at Universal. After all, there were women on the other side of the partition, inking and painting cels, and she initially had worked on that side, too. One day she simply moved, having gotten the promotion that changed everything, but there was nothing glamorous about any part of Universal’s cartoon unit. It was all housed in the same ramshackle building.

In the early part of her career, Harding fraternized after hours and she didn’t mind drinking with the animators or tagging along to the racetrack and betting on horses. It was a fun, carefree time for her. It helped her get to know her boisterous colleagues and they readily accepted her as a peer. It was only through the disapproval of her mother that she slowly curtailed going out with them.

Then there was the tragedy of her brother Bill Harding, who was a Navy test pilot. He died in a plane crash in 1936 while trying to save another officer’s life. This threw a pall over the family. As Judy informed me, the death forever changed them, marking a turn toward religiosity to help deal with their grief, but La Verne never chose to forsake aircraft. It turns out Bill could draw cartoons and she dreamed about aviation. They were kindred spirits. Probably Bill had gotten her hooked on planes and this was a way to keep his memory alive.

Bill Harding, on left, during his service as a Navy pilot in 1936.

In later years, she took her nephew to airports and instilled in him a knowledge of aircraft, right down to small details and model specs. She helped Jon be able to name any plane on sight, a skill they honed while sitting along the runway together. La Verne was also a bit of a gearhead. She liked the simple engines of Ford automobiles in the 30s and 40s. She could fix carburetors and spark plugs with only bobby pins as her tools.

Harding was a confident modern woman who knew what she liked and didn’t. She didn’t like her clothes with too many ruffles, yet when she drew cartoons, her characters were cutesy and rounded. Her nieces recall that Aunt Verne always seemed to put a fluffy bow on the characters she made for them. At the studio, she was a dominant force in the trend toward cute characters driven by Disney cartoons.

As competitors tried desperately to emulate Disney, there were two animators at Lantz who could lead by their own example: La Verne Harding and Manuel Moreno. The first generation of New York animators, men like Bill Nolan, had grown irrelevant. Nolan was basically pushed out of Universal, yet in contrast, Harding’s value to Lantz was on the rise. His decision to hire her on to staff in 1932 looked prescient by the end of the decade.

As competitors tried desperately to emulate Disney, there were two animators at Lantz who could lead by their own example: La Verne Harding and Manuel Moreno. The first generation of New York animators, men like Bill Nolan, had grown irrelevant. Nolan was basically pushed out of Universal, yet in contrast, Harding’s value to Lantz was on the rise. His decision to hire her on to staff in 1932 looked prescient by the end of the decade.

Then at some point, perhaps through her circle of friends from Trinity Methodist Church, she made the acquaintance of a professor from UCLA. He proposed to her with a spectacular five-and-a-half carat sapphire ring and she accepted, but something happened. Even her close-knit family may not have known exactly what she wrestled with as she stared at her engagement ring.

There are examples in film history that illustrate what was at stake for a woman of her time. For instance, when the animation producer Margaret Winkler was still single, she had the freedom to finance and distribute Disney’s Alice Comedies. However, after she married Charles Mintz, he effectively controlled her production company and he turned on Disney. It seems likely that Winkler acquiesced because she had to, watching her husband alienate the talent she had cultivated.

The social norms put newlywed women at a disadvantage, even if a husband were supportive. Employers might say, “Well, she’s married now” and find reasons to be dismissive. There was never a suggestion that Lantz was inclined this way and in fact he was becoming reliant on Harding. The point I make here is simply that society imposed a pernicious double-standard and a solution became evident to her.

La Verne was left to ponder whether she wanted to be Mrs. UCLA Professor. Her fiancé dazzled her with a stunning ring, but it wasn’t what she wanted for her life, not if it took her away from animation. The way Marlene described it is how the family recalls the dilemma, an event that recedes across eight decades and yet still hangs there with resonance. La Verne Harding felt she had to make a choice between being married or having a career. She called off the engagement.

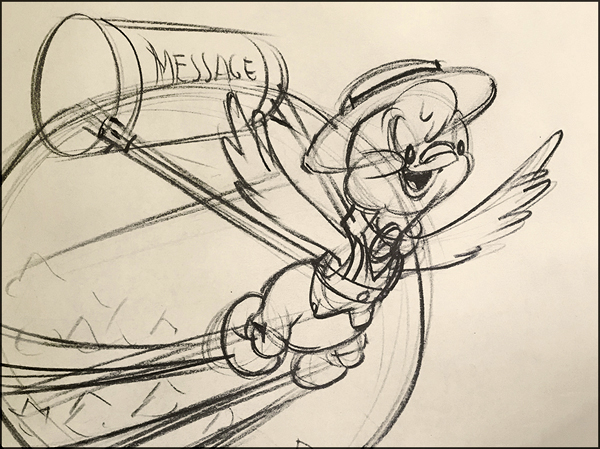

Life would go on, as inevitably it does, and World War II came next. As an animator in Hollywood, she was fortunate to avoid the direct ravages of wartime. She had the opportunity to serve a role for the U.S. Navy, just like her brother Bill, but she did it from the safety of her desk at the Lantz studio. She animated the microbes that slosh around in a patient’s body for the military training film, The Enemy Bacteria. She also animated Andy Panda in Air Raid Warden and Homer Pigeon in Pigeon Patrol, among many others.

Homer Pigeon

It was during the post-war Baby Boom that she became an aunt. She was excited when Judy and Marlene and then Jon were born. This became a very active part of her life, having them over on weekends, planning excursions with them, and making them feel special on birthdays and Christmas with her generous gifts. Judy wrote me that Aunt Verne “would entertain us and would draw little animals on napkins as she told us stories.”

In 1954, her Ford was getting on in years, so she asked Marlene what new car she should buy. Marlene was just a little girl and she answered, “A red car!” To her astonishment, Aunt Verne returned with a brand new, bright red Mercury Monterey Coupe. It was a two-door hardtop convertible with smooth-riding front suspension. I asked Marlene how this car made her feel and she said, “Very impressed.” For Harding, buying that red Mercury was a chance to make her niece glow with pride, but it must have also turned heads over at the studio.

She commuted to Walter Lantz Productions on 861 Seward Street. With negotiations soon to bring The Woody Woodpecker Show to television, Lantz was knocking on fortune’s door. His lean years as a producer were now in the rear-view mirror and Harding had been there for him as an ally. As requests go, hers were humble. She only wanted to give Judy, Jon, and Marlene the chance to see the studio.

There were three occasions when Aunt Verne brought them in for special visits. They were taken all around to each department and Walter was a gracious host to the little visitors. To this day, Marlene still has the artwork that Lantz drew for her as a keepsake. They capped off each visit with cartoons in the screening room. And as a treat, they saw a “premiere” of a forthcoming release.

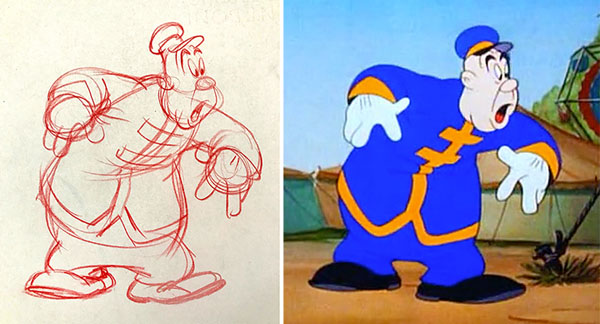

Harding animation in “Dizzy Acrobat” (1943)

Tex Avery worked briefly for Lantz on Seward Street, directing just four cartoons in a period from late 1954 to 1955. This served as a reunion for Tex and La Verne. They both came up as young animators together at Universal. The timeframe of these four cartoons makes it nearly certain that Avery was around to be envious of her ’54 Mercury coupe. He may have even been there to behold it on the day of its arrival.

With that in mind, it’s time to revisit Crazy Mixed-Up Pup for the conspicuous ‘easter egg’ that incites the cartoon. Since the family contends that Aunt Verne gave Tex the film idea, let’s recap: Sam takes his dog for a walk and then, when they both get hit by a car, a mix-up occurs during a plasma transfusion. Sam and his pup switch behaviors.

The ‘easter egg’ is the car. A red coupe streaks through and flattens the characters. Although red would be the obvious color to give a car that spends only a few frames on-screen (for emphasis, for impact, for BAM!), it’s intriguing to wonder if this was an homage. Harding was Avery’s old friend, she was his animator with top credit, and she deserved some form of acknowledgement if she inspired the film.

The ‘easter egg’ is the car. A red coupe streaks through and flattens the characters. Although red would be the obvious color to give a car that spends only a few frames on-screen (for emphasis, for impact, for BAM!), it’s intriguing to wonder if this was an homage. Harding was Avery’s old friend, she was his animator with top credit, and she deserved some form of acknowledgement if she inspired the film.

A frame-by-frame inspection does reveal the car’s driver for just a fleeting moment. It’s a man, not a woman, and so admittedly this theory takes a hit. I was deflated myself when I realized it wasn’t a mischievous caricature of La Verne behind the wheel. However, it also doesn’t quite debunk the idea. There could still be reasons why her red Mercury made the cut and she didn’t. So I leave that to you to dissect and debate. Please comment below, I’d love to know your thoughts.

For me, just the idea of her Mercury zipping through that cartoon and setting events in motion is a perfect metaphor. La Verne Harding still has not accrued the kind of rich legacy she deserves, at least in terms of name recognition from fans, but her quiet influence played a role in shaping Lantz cartoons for over three decades. We might not ever know if the cartoon Mercury was hers, but if not, it’s a crazy mixed-up puzzle.

With many thanks to Judy Usik, Katherine Usik, and Marlene Johnson for their assistance and for the personal history of Aunt Verne shared by Judy and Marlene. Photos and illustrations above are courtesy of the family archive, which includes over a thousand original production drawings and animation sequences from Harding’s work on classic films. Some collectibles and drawings are available for sale. For serious inquiries, contact Judy Usik at jusik@verizon.net. Efforts are presently under way to make a digital archive available to scholars through the library of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

If anyone had suggested using a caricature of La Verne Harding as the hit-and-run driver responsible for Sam’s accident in “Crazy Mixed-Up Pup”, I think she would have vetoed it immediately. This strong, capable career woman, who knew her way around the engine of a car, would probably not have taken kindly to “woman driver” jokes. I’ll never forget how my wife blew up when she saw the “Jane’s Driving Lesson” episode of The Jetsons.

This is an excellent article — and that ’54 Mercury is a very snazzy car!

“There are examples in film history that illustrate what was at stake for a woman of her time. For instance, when the animation producer Margaret Winkler was still single, she had the freedom to finance and distribute Disney’s Alice Comedies. However, after she married Charles Mintz, he effectively controlled her production company and he turned on Disney. It seems likely that Winkler acquiesced because she had to, watching her husband alienate the talent she had cultivated.”

I don’t recall this issue ever being addressed before. Not from Margaret’s point of view. I’ve often wondered what Margaret’s thoughts were on Charles’ treatment of Disney. Certainly something changed after she married Mintz.

But considering the status of women at the time, similar reasoning may apply to the question of why the character in the car was male and not female. While cartoon violence was not off-limits to female characters–witness “Don Donald” or the ending of “Cured Duck”–the vast majority of the time, it was male characters involved in the more violent aspects of the cartoons. But an even simpler explanation could be that Avery didn’t want to be too obvious about his sly tribute to La Verne and her colorful vehicle.

It was a good read, but the statement that she does not have “the rich legacy she deserves” has me puzzled. Besides being a woman, what did she do that advanced the art, or would make us recognize her work today? It appears that she did her job, and did it well, but then so do most people.

Harding’s influence on character designs is one of her notable contributions, starting with the way she drew Oswald and Lantz studio characters in the 1930s. Based on production documents, she was getting big assignments by the later part of that decade, meaning that her animation was putting a thumbprint on the studio output. For instance, she was the primary animator on “Kittens Mittens” (1940) because she was a specialist in cute characters. And let’s just say that, if talent is the best judge of talent, Tex Avery saw what she could bring to his cartoons. La Verne animated the classic clarinet lullaby sequence in “Legend of Rockabye Point”, among others. Avery had even tried to recruit Harding to be part of his original Termite Terrace unit. She’s also largely responsible for elements of the Woody Woodpecker redesign of the 1950s. I could go on, but maybe I’ll save this for yet another post! It’s very gratifying turning up more stories and more evidence for why we should be taking a closer look at her work. So, I really do stand by my statement that she “does not have the rich legacy she deserves.” I think in her situation, the prudent professional decision to remain with Lantz for so long, to not work at another studio until 1960, has lowered her overall profile in film history. But that profile can change, yes? There’s plenty of legacy in plain sight, even if it zips by unnoticed like a speeding Mercury.

Laverne Harding did her job extremely well. She was a favorite of not just Tex but Shamus Culhane, Dick Lundy, and Alex Lovy, too. The scenes in the Lantz cartoons that are the most solid/dimensional, re: “Perfect” are almost always hers, making her the Bob McKimson/Ken Harris/Ken Muse of the studio. And Tom can correct me if I’m wrong, but Harding also filled in as an assistant director, maybe even co-directorship, role on some of Lovy’s Lantz cartoons. So yes, Laverne Harding did a remarkable job, and the fact that she was any of these guys’ equal (and superior in many cases) in a boy’s club industry makes her even more remarkable.

It always bothers me that talk of “oh, look, a woman doing animation, what an incredible thing”, as if there was something about being a woman that made the fact that she was an animator something otherworldly. As you said, a professional who did her job. I also don’t much agree with this suggestion that there was some form of prejudice against women in the animation industry, since the ink & pain departments were dominated by them. Or couldn’t the girls at I&P get married too?

“Well gee, she only managed to be a top animator/designer on major characters and was really highly regarded by the best director ever, what else did she do, are we supposed to be impressed just cuz she’s a girl?”

Wow, that Merc’ is bitchen! Tuff! Boss! Rad!

But I’m thinking ANY connection between it and the car in CMUP is a stretch, at best.

The cartoon car is brown, fercryinoutloud.

She may not be mentioned in the same breath as Chuck Jones, but it’s plenty enough for me to consider LaVerne Harding the primary creator of the visual style at Lantz.

You say the cartoon car is brown. Tom says it’s red. I say, what a maroon!

That’s a beautifully written piece. I agree that she deserves more attention, and not just for the distinction of being perhaps the standout female animator of that period, although that’s important to note. The color and context you add to her story here is really invaluable. Kudos!

I am La Verne Harding’s great-niece (Marlene’s daughter). I’d like to thank you so much for such a fantastic piece on her. She died when I was about 10, but she’s one of the reasons I became an artist myself, and I loved reading something so informative and impressive! Thanks again!!

Hading’s screen credit in the 1940’s was Verne Harding (not LaVerne), I’m surprised this was not touched upon in this piece about her

Is there any way of knowing if Harding was the one who animated the man and dog getting run over? Someone get Devon on the line!

There’s also a nod to a previous Avery cartoon. Rover does the same dance that the dog Speedy does in “Doggone Tired”. Also, Sam orders “a big, thick, juicy T-bone steak” from the butcher, quoting verbatim from “What’s Buzzin’, Buzzard?”, though that might just be a coincidence.

Excellent piece, Tom. Your valuable historical posts on the Lantz studio are some of the best and most thought-provoking pieces here.

Any idea why Harding didn’t become a full time director? I think she’d make a better director than another animator got the chance (and completely wore out his welcome).

Thanks everyone for all the comments. Some good points to address here, and let me start with speculation that’s mentioned and I’ve only heard second-hand: that Avery was so reliant on Harding that she was like a co-director to him at Lantz or that maybe she finished his last cartoon. We know they had a strong working relationship, but from various evidence of that period, I would dispute that Harding was ever standing in as a director (and then I’ll get to how that perception may have started).

When Tex Avery got to Lantz, he was not only firmly in charge of his cartoons, but also sought to bring his animators up-to-speed with new expectations. Ken Southworth once told me how Tex gave them tips on how he wanted them to animate, to set the bar higher. La Verne told Joe Adamson that unlike how others may have perceived Avery’s directing style, she really enjoyed working with him because he knew exactly what he wanted and provided a clear vision. In that interview, she said she could never “get over how perfect Tex was.” She rose to his challenge and therefore played a big role in those cartoons, but she did not not direct or co-direct.

In speaking to Judy and Marlene, there also was not mention that Aunt Verne ever said she wished to be a director, although I don’t doubt she would have been a good one. With all her additional professional work in comics and illustration, Harding was excellent at layout and story progression. And she knew timing from all her years animating. Here’s where I think this comes into play: she would direct herself. The director Alex Lovy stated that he would provide exposure sheets and instructions for other animators to follow, but that he would just let Harding time her scenes the way she wanted. It would seem he held her in a special regard and, in a manner of speaking, let her be the director of her own scenes.

Also, Barry’s comment: you mention about her screen credit usually being Verne, which was the name that most people called her in the studio. It was always La Verne on the “Cynical Susie” comic strip and appears this way on “Crazy Mixed-Up Pup.” It’s an interesting spelling, being divided into two distinct words with a space between, not Laverne. This I believe is due to a Southern origin, as it was a family name. It also made the name easy to masculinize or make neutral. It seems that Margaret Winkler used initials professionally so as not to call attention to her gender, for instance. There is that aspect to consider, working ‘under cover’ in the early days of animation, but La Verne really did casually go by Verne (by many people who knew her full name), including her nieces who lovingly called her Aunt Verne or sometimes Aunt Vernie.

A last anecdote to share. At her funeral in 1984, she had a pink casket and was dressed in pink as she was interred at Inglewood Cemetery. It was her wish to be fabulous right to the end! And what happened to the red Mercury? Her nephew Jon had been given the car and he fully restored the engine, a chance to turn more heads as Aunt Verne’s ’54 hardtop convertible continued to vroom around Los Angeles.

Hey, Tom, thanks for clarifying, that was EXACTLY what I had remembered re: Lovy and Harding’s working relationship, but I was having trouble remembering where and what exactly I had heard. And here you spelled out as it needed to be. As you know, no term has more fluidity than “direction” in an animated production, and a lot of people brought up in the studio system of the ’40s and ’50s considered timing a form of direction. Re: if you timed it, you directed it. (Ralph Bakshi certainly is an ardent believer in this.) So, understandable if some miscommunication happened. And it makes Laverne Harding even more remarkable that she was doing even more important work behind the scenes. Thanks again, and it goes without saying, but excellent article.

Tom, your posts are always a treat for the eye, and as well as Adamson’s interviews are the prime contributors to Lantz and his staff being finally reevaluated to their just merits.

I gotta ask though, did Verne had a hand in helping Tex redesign Chilly Willy into the — honestly much more lovable — design we know today? I don’t think he would have had the same lasting appeal to warrant having his own series without Tex (and Verne’s) involvement, and seeing how we got from a generic and lifeless first entry to I’m Cold and The Legend of Rockabye Point I’m fairly sure Walter would agree.

Laverne Harding used “Verne” as a sort of shorthand for her name. I found an image on line of a layout from “Hay Rube” on which she wrote a note to Ray Jacobs reminding him not to paint the background until changes were made to the ornaments on a Christmas tree shown in the layout, and signed “Verne.”

LaVerne Harding was one of the best artist in her life! And having to make it in a man’s world. I’m glad Lantz studio reconized Laverne

Although I (and countless others) who watched the many antics of Woody Woodpecker, Yogi Bear, and laughed at the Pink Panther and others, I just want to acknowledge that Master Animator La Verne Harding made for decades a lot of children happy in seeing those Cartoons (as I did) after school, and on Saturdays Morning very special! Often more than not, many of us who watched these Cartoons could have cared less when the CREDITS WERE ROLLED on who drew them; but over the last few decades, I really became interested more on who these talented folks were! So…to you Tim, for writing thess great articles on La Verne Harding, to her nieces Judy and Marlene, your Auntie was indeed so blessed with talents she shared with the world and all of us…Thank You for adding more to the story of a “Trailblazing Animator” who definitely PAID her dues! What was missed by other comments, this dear lady La Verne also went to Church every Sunday…she NEVER forgot the God that created and loved her, gave her the blessing to also create too! Be Blessed Everyone!