On this day in 1951, one of Disney’s most offbeat and unfathomable animated features premiered–but it took seven more years for the story LP to appear on Disneyland Records.

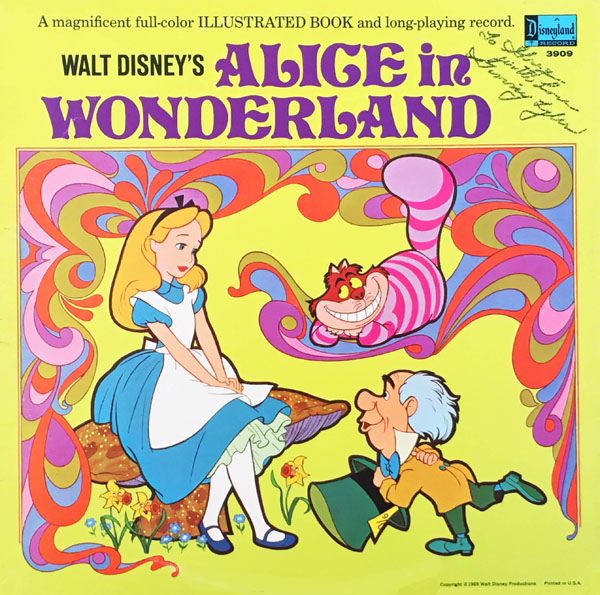

Walt Disney’s ALICE IN WONDERLAND

Story and Songs from the Motion Picture

Disneyland Records ST-3909 (12” 33 rpm LP with Book / Mono)

Originally Released in May, 1958. Executive Producer: Jimmy Johnson. Producer/Musical Director: Camarata. Running Times: 21 Minutes (Darlene Gillespie Version); 24 minutes (Ginny Tyler Version).

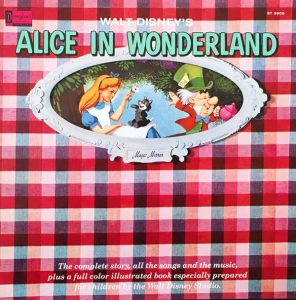

LP Reissued in 1962 and 1967 (Magic Mirror Plaid Covers), 1969 (Groovy Cover), 2018 (“Vinyl Vault” Magic Mirror Plaid Cover)

Songs: “Alice in Wonderland,” “In a World of My Own,” “I’m Late,” “The Caucus Race,” “The Walrus and the Carpenter,” “All in the Golden Afternoon,” “Very Good Advice,” by Sammy Fain, Bob Hilliard; “’Twas Brillig,” by Don Raye, Gene DePaul; “The Unbirthday Song,” by Mack David, Al Hoffman, Jerry Livingston.

Instrumental: “March of the Cards” by Sammy Fain.

Many believe the Walt Disney version of Alice in Wonderland to be the one of the few feature films to come close to capturing Lewis Carroll’s dreamlike, non-linear books and gain greater appreciation with each generation.

The 2010 Tim Burton version was the first Alice adaptation to be a box office hit out of the gate, but a story thread was needed in order for Alice’s adventure to “made sense” and “send a message.” The very things that make Carroll’s books so eternally compelling is that they defy all sense and that the audience is given the option of interpreting them—or not—”and when you come to the end, stop… see.”

The 2010 Tim Burton version was the first Alice adaptation to be a box office hit out of the gate, but a story thread was needed in order for Alice’s adventure to “made sense” and “send a message.” The very things that make Carroll’s books so eternally compelling is that they defy all sense and that the audience is given the option of interpreting them—or not—”and when you come to the end, stop… see.”

Walt Disney and his artists could never really tame this beast of a fantasy. The finished film was not among Walt’s favorites—although the Wonderland concept was of constant fascination throughout his career, from the Alice in Cartoonland series and his first TV special, One Hour in Wonderland (promoting the 1951 Alice), to the popular Alice in Wonderland ride and Mad Tea Party teacups park attractions.

Ultimately, the film is one of a select few classics that only gains momentum as the world catches up with it. Ward Kimball (who contributed the acerbic Cheshire Cat and unhinged Mad Tea Party sequences) called the movie a “loud-mouthed vaudeville show.” Maybe it was to a degree. So are Looney Tunes cartoons, Marx Brothers comedies and Monty Python sketches. It took on a life of its own, a Young Frankenstein monster of animated design, music and madness. that even its creator could not contain. Surely no one in 1951 expected this sort of thing from Disney—much less a confident, outspoken female character like Alice, who did not suffer fools and stood up to authority. Don’t let’s be silly!

[As of last Friday on Cartoon Research, our wondrous friend Jim Korkis has by coincidence started a multi-part series on Disney’s Alice, and its journey to the screen. I not only urge you to enjoy it but also the comments which share the same acknowledgment of the 1951 film as a definitive masterwork.]

[As of last Friday on Cartoon Research, our wondrous friend Jim Korkis has by coincidence started a multi-part series on Disney’s Alice, and its journey to the screen. I not only urge you to enjoy it but also the comments which share the same acknowledgment of the 1951 film as a definitive masterwork.]

As we covered in previous Animation Spins, particularly this one about The Greatest Record Album Ever Made, there was no soundtrack album for Alice in Wonderland until the CD in 1997. Briefly, Decca had purchased the rights but dropped the option. The newly-minted Disneyland Record company decided to record a studio version with their musical director (and Disney Legend), Tutti Camarata, and multi-talented Mickey Mouse Club Mouseketeer Darlene Gillespie.

Walt Disney’s Alice in Wonderland, Music from the Score Conducted by Camarata (which can be downloaded at Amazon, iTunes, Spotify or on vinyl picture dischttps://www.disneymusicemporium.com/product/XVLP32/alice-in-wonderland-picture-vinyl). It was recorded in 1957 at Hollywood’s famed Capitol Records building with an immense orchestra and chorus (Norman Luboff may have been involved with assembling the singers, the female voice in “’Twas Brillig” could be his wife Betty; Thurl Ravenscroft can also be heard clearly in the ensemble).

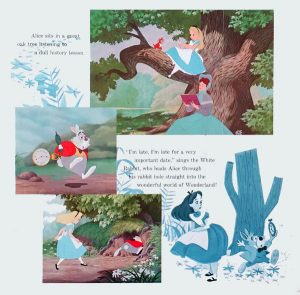

Darlene was narrated the story on one of the earliest albums in the original “Storyteller” LP record and book series. Her narration bridges each of the songs, while some of the music bridges and instrumentals also play while she speaks. Released in 1958, the album had a glossy book inside the gatefold cover with short text, line art and color images from the film.

When the ABC-TV network canceled the Mickey Mouse Club, Disneyland Records re-recorded and repackaged most of the Storyteller albums to replace the Mouseketeer narrations by Darlene Gillespie from Alice, Annette Funicello from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (see this Spin) and Jimmie Dodd from Peter Pan and Bambi (see this Spin).

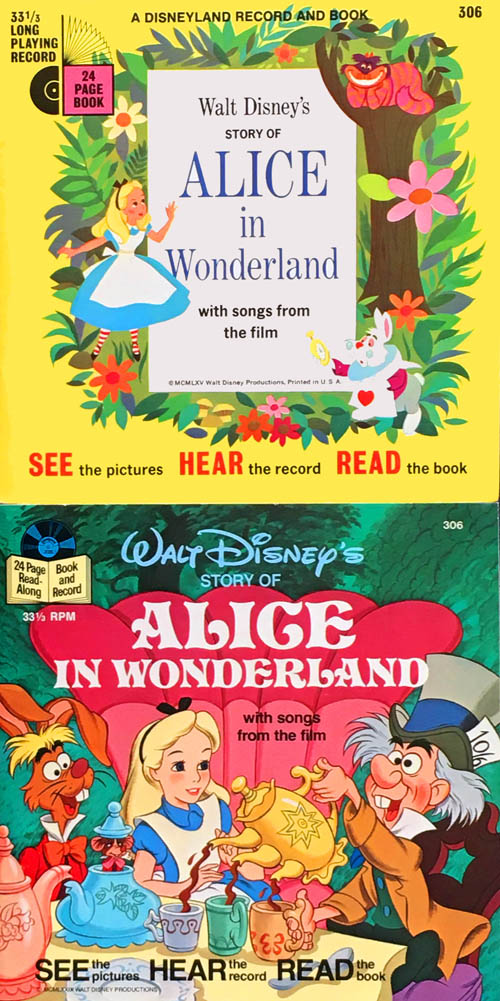

Each new gatefold cover did not mention a narrator at all, but did include an intriguing “Magic Mirror.” This was a die-cut oval revealing a portion of the front page—a clever selling tactic because one could not see the whole illustration without buying the record! Surrounding the Magic Mirror was a photograph of a fabric pattern selected by the art director to complement the illustration and the theme of the story. Alice was given a simple plaid checked cloth fabric, as opposed to an elegant satin for Cinderella, or a forest green fabric for Peter Pan, etc).

Disney Legend Ginny Tyler performed all the scripts as they were originally written with only a few revisions. She is not credited on these albums, but introduces herself as the “Disneyland Storyteller.” She begins the Alice LP with a transitional device: “I’ll be Alice… Alice in Wonderland!” and continues in character as a little girl. She does the same on the Cinderella Magic Mirror Storyteller, upon which her narration replaces Cliff Edwards as Jiminy Cricket (see this Spin).

Darlene portrayed Alice basically as herself, a personality in the role she created as the singer on the album and a performer on the Mickey Mouse Club. Her performance is not slick or polished but is natural, unpretentious and even quite amusing.

A master of voice acting, Ginny Tyler plays every role as a separate entity, not just as a ‘different’ voice. Everything about her performance is top drawer—the pacing, breath control, diction—and most important and difficult, the choice of how to emphasize the words. One can vary the tone just for the sake of not sounding repetitious and it becomes a sing-song. There does not seem to be a Ginny Tyler narration in existence that is not on the button.

However, there’s no getting away from the fact that this was not Ginny’s script—and not her songs, because Darlene was still singing. It is a challenge that she rises to admirably. It works, because lots of Storytellers were narrated by actors who were not necessarily in the soundtrack portions of the records, but for those who know the Darlene version, the original works better—which is ironic because Darlene isn’t the original Alice, either, but her identity on the Camarata album was attached to her narration. One thing must have been fir sure—the narration was specifically designed to flow in and around the songs and instrumentals from Camarata’s album.

When the Magic Mirror series was being produced, Disneyland Records was struggling with cost-cutting measures to stay in existence. For this reason, some steps were skipped when making the re-recorded Storyteller albums. Back in 1958, Alice in Wonderland Storyteller was produced by recording Darlene’s narration and sometimes timing it when it needed to be inserted within the bridge of a song. Then it was fitted over the various instrumental sections, inside the song bridges and between the songs.

When the Magic Mirror series was being produced, Disneyland Records was struggling with cost-cutting measures to stay in existence. For this reason, some steps were skipped when making the re-recorded Storyteller albums. Back in 1958, Alice in Wonderland Storyteller was produced by recording Darlene’s narration and sometimes timing it when it needed to be inserted within the bridge of a song. Then it was fitted over the various instrumental sections, inside the song bridges and between the songs.

After Ginny Tyler recorded her 1962 replacement narration, it would have taken time and money to go back to the music tracks, time some of it, place her narration over the sections again, making sure they match, etc. Instead, her narration was recorded “wild,” with no need to time (note that her version is a few minutes longer, allowing her the freedom to slow down and play with the voices). When Darlene’s narration was present on the tape over some music, or heard on a portion of a song, it was either cut or faded. This saved hours of studio time, resulting in much-needed cost savings in 1962–when the record company faced closure unless it kept making more and costing less. Annette’s pop records had kept the label afloat since 1959 and that lead to what was still a few years away—the recording success of Mary Poppins, which solidified the Disney Music Group to this day.

Throughout the sixties and seventies, it was very possible to buy a Magic Mirror or an even later edition of a Storyteller album and still find a Mouseketeer narration inside. The supply of early LP versions must have been plentiful. Perhaps the old covers were discarded when a new cover was printed and the remaining early records were placed into new covers. Disneyland Records must have known this because none of the subsequent covers was very specific about the narrators unless they never changed (like Cliff Edwards as Jiminy Cricket, who was NOT replaced on Pinocchio, as explored in this Spin).

Throughout the sixties and seventies, it was very possible to buy a Magic Mirror or an even later edition of a Storyteller album and still find a Mouseketeer narration inside. The supply of early LP versions must have been plentiful. Perhaps the old covers were discarded when a new cover was printed and the remaining early records were placed into new covers. Disneyland Records must have known this because none of the subsequent covers was very specific about the narrators unless they never changed (like Cliff Edwards as Jiminy Cricket, who was NOT replaced on Pinocchio, as explored in this Spin).

To millions of listeners, the Magic Mirrors were narrated by whoever was on the record inside regardless of the date on the cover. Even in 1969, when the cover sported the super groovy artwork that was used five years later when the film was reissued for its second time in 23 years (and the film stills were replaced by painted illustrations), it was conceivable that the 1958 version could be inside.

[Anecdotally, I received my first copy of the 1962 Alice Magic Mirror album in 1966. The 1958 Darlene Gillespie record was inside and it was over ten years before I even realized that Ginny Tyler recorded her own version. In the late seventies, my brand-new copy of the 1969 Snow White Storyteller with the purple cover had the 1957 Annette-narrated LP was inside.]

Darlene’s Narration – Excerpts from the 1958 Storyteller

Darlene was sixteen (going on seventeen), and about five years older than the movie voice of Alice, Disney Legend Kathryn Beaumont. Either the Storyteller script was written to fit her TV persona as an American TV teen of the 1950s, or she just made the lines work in her own style. It’s always fascinating to compare two different interpretations.

This is the 1962 Magic Mirror version narrated by Ginny Tyler:

Walt Disney’s Story of ALICE IN WONDERLAND

With Songs from the Motion Picture

Disneyland Story Reader: Robie Lester

Disneyland Records LLP-307 (7” 33 rpm LP with Book / Mono)

Released in November, 1965. Executive Producer: Jimmy Johnson. Producer/Musical Director: Camarata. Running Times: 9 Minutes.

Songs: “I’m Late,” by Sammy Fain, Bob Hilliard; “The Unbirthday Song,” by Mack David, Al Hoffman, Jerry Livingston.

Our beloved Robie Lester in one of her first “Original Little Long-Playing Reh-Kords,” reading Jane Werner’s Little Golden Books adaptation entitled “Alice in Wonderland Meets the White Rabbit.” Robie calls it “Alice in Wonderland, and How She Met the White Rabbit.”

This text was also recorded by Lucille Bliss [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XzhRTOCbCsM] for Disney’s Peter Cottontail album, which was in this Spin.

Walt Disney’s Story of ALICE IN WONDERLAND

With Songs from the Motion Picture

Disneyland Records #307 (7” 33 rpm LP with Book / Mono / also on cassette)

Released in 1979. Read-Along Producer: Jymn Magon. Narrator: Linda Gary. Musical Director: Camarata. Running Times: 12 Minutes.

Cassette Reissue: 60437-4 (1990)Voices: Patty Parris (Alice); Linda Gary (Narrator. Queen of Hearts); Corey Burton (White Rabbit, Mad Hatter, Tweedle Dee); Jymn Magon (Tweedle Dum, Three of Clubs). Caucus Race characters played by the cast.

Songs: “I’m Late,” “The Caucus Race” by Sammy Fain, Bob Hilliard; “The Unbirthday Song,” by Mack David, Al Hoffman, Jerry Livingston.

Instrumentals: “Alice in Wonderland,” “In a World of My Own,” “I’m Late,” “The Caucus Race,” “The Walrus and the Carpenter,” by Sammy Fain, Bob Hilliard; “March of the Cards” by Sammy Fain.

One of the finest of Jymn Magon’s late-seventies “new wave” of Disneyland read-alongs that added a cast, music and sound effects. The text was similar with alterations to fit the dialogue and to work the songs into the narrative rather than putting them at the end.

The Camarata album provided a rich library of cues for the background. Listening carefully, it is possible to hear the vocals in some of the background music. The songs had the vocals mixed down to be barely audible so they could be used as underscore.

Alice in Wonderland was revamped as a read-along once more in 1999 (#60437-2) by Randy Thornton and Ted Kryczko in 1999. For the first time, Oliver Wallace’s background music from the 1951 film soundtrack was heard in the background. Roy Dotrice narrated. Originally released exclusively on cassette, it is now out of print but would most likely be the current version if reissued in the future by Disney Publishing, which now releases CD read-along packages.

Alice nel Paese delle Meraviglie – Camarata Orchestra with Italian Chorus

Salvador “Tutti” Camarata must have loved this gorgeous vocal arrangement in his native family language version over his original orchestral track.

GREG EHRBAR is a freelance writer/producer for television, advertising, books, theme parks and stage. Greg has worked on content for such studios as Disney, Warner and Universal, with some of Hollywood’s biggest stars. His numerous books include Mouse Tracks: The Story of Walt Disney Records (with Tim Hollis). Visit

GREG EHRBAR is a freelance writer/producer for television, advertising, books, theme parks and stage. Greg has worked on content for such studios as Disney, Warner and Universal, with some of Hollywood’s biggest stars. His numerous books include Mouse Tracks: The Story of Walt Disney Records (with Tim Hollis). Visit

Last Friday’s column on Cartoon Research inspired me to watch “Alice” again last weekend, and afterward I was reminded of a Disney-Alice-music connection that you might not be aware of.

In 1917 Deems Taylor, the music critic and radio commentator who introduced the musical numbers in Walt Disney’s “Fantasia”, composed “Through the Looking Glass”, a five-movement suite for an ensemble of ten instruments based on Lewis Carroll’s work. Several years later he arranged the suite for full orchestra. The movements are titled (1) Dedication; (2) The Garden of Live Flowers; (3) Jabberwocky; (4) Looking-Glass Insects; and (5) The White Knight, and a complete performance of the work lasts about thirty minutes.

Taylor’s music was highly regarded in its time. To date his operas have been staged by New York’s Metropolitan Opera more than those of any other American composer. I have an old biographical dictionary of composers published in 1940, in which the entry for Taylor is as comprehensive as the one for Tchaikovsky, immediately following alphabetically. (The fact that Taylor edited the dictionary might have something to do with that.) Unfortunately, as with many American composers of his generation, Taylor’s music has fallen into obscurity. For example, the Boston Symphony Orchestra performed “Through the Looking Glass” six times between 1932 and 1941, but not at all in the years since.

Although Taylor championed modern music — he was the one who pushed to include Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring” in “Fantasia” — his own music is in a more old-fashioned, lyrical, Romantic style not dissimilar to the scores of early Disney features, or the storyteller records discussed here. I find “Through the Looking Glass” evocative and very beautiful on a sensual level, but somewhat lacking in dramatic power, always running out of steam just when it seems to be building momentum.

There are several old recordings of “Through the Looking Glass” available online, but I recommend the 1990 Delos recording with Gerard Schwarz conducting the Seattle Symphony if you can get your hands on it.

Thanks for a “wonderful” post, and I look forward to the next journey down the rabbit hole on Cartoon Research. Happy anniversary, Alice! And a very merry un-anniversary — and a frabjous day — to the rest of us!

One “curiouser and curiouser” fact (to quote Alice) is the manner in which the script is written, which takes the episodic nature of the Disney re-interpretation and makes it even less linear than it is in the film. The narration is a bit haphazard, as Alice relates “one time” this happened and “another time” this other thing happened. Not that this is at all inappropriate, considering the dreamlike nature of the adventure in the first place, but any nod to sequential continuity (which might be found, for example, in the ongoing plot thread of Alice’s pursuit of the White Rabbit) is not as evident as it might be. Furthermore, this script, unlike its fellows in the Disneyland Storyteller series, supposes a prior familiarity with the story. An example of this is when Alice says, “I met the famous Cheshire Cat–grin and all.” To a first-time listener who may or may not have seen the movie or read the original book, this reference might not be clear. To one who has not heard of the Cheshire Cat before, it might not be understood how the cat could be referred to as “famous” or what the “grin” reference was all about. The other scripts treat unique events in their stories as though they are unfolding for the first time, regardless of how “familiar” the story may already be to the listener.

These “curiosities” do not diminish the luster of the recordings. They just add an unusual factor. I came upon both the Ginny Tyler and the Darlene narrations as an adult, so of course I listened to them with different “ears” than if I had first heard them as a child. The Ginny Tyler version was the first one that I heard. When I later heard the Darlene version, I liked it better–possibly because Darlene’s voice at the time was closer in age to the character she was portraying. But now, having had multiple opportunities to hear both, I can appreciate the artistry of each of these excellent young ladies. Your assessment of the differences between them is spot-on, and I agree with your verdict that comparison skews more in favor of the Darlene version. It’s also noteworthy that neither of them essays a British accent.

I appreciate your focus on the recordings for Disneyland Records above. Though it does not belong in this particular article, there is of course an earlier version, which I believe you have written about before, and which featured the voices of Kathryn Beaumont and Ed Wynn, along with several others of the original cast, plus Arnold Stang as the White Rabbit. In this version, Alice spoke with a British accent, the story was presented in a more linear fashion, and the narration presented the various episodes as if they were new information–all of these “rules” were “broken” in the Disneyland Records Storyteller script. Also intriguing were the very brief snippets of the songs, which were played just long enough to establish a few of the lyrics, and then the narrative moved on. Another contrast to the lush orchestrations of Camarata for the Disneyland albums, and their presentation (for the most part, at least) as full songs.

Thank you for reproducing all of the covers of the variant editions of these records. I especially appreciate the “surprise picture” from inside the Magic Mirror version. I have long wanted to see it.

This is something I always wanted to know: How come “Alice in Wonderland” and “Dumbo” were shown on the anthology show early on unlike being restricted to be shown in theaters every seven years?

My understanding is that both “Alice” and “Dumbo” had under-performed at the box office–“Dumbo” due to the fact that WWII erupted at the exact moment it was being released, and so it never got the full exposure it would have received if it could have been exhibited as usual in the U.S. and overseas. “Alice” though released long after the war did not win the hearts of the critics or the public to the extent that Disney had hoped. (But I would never refer to it as a “failure” in any sense, although others have considered it as such.)

When the anthology TV series debuted, the viewing audience needed to be brought back week after week, and since Disney at the time was chiefly known for animation, many of the early shows were either compilations of older cartoons with new bridging animation, or replays of animated features. At some point, nearly every feature in the canon was referenced in clips, depending on a particular show’s theme. “Alice in Wonderland” due to its episodic nature could be trimmed to fit the 50 minute air time (allowing for commercials). “Dumbo” with a running time of only 64 minutes could be shown virtually intact with very minor edits.

These are only guesses, based on what I know of Disney history. What I can attest to is that my first viewing of “Alice” was when it was shown in the early 60’s on “Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color” (which ironically we watched on a black-and-white TV set). Two things stand out from that first viewing. I loved the scene where the White Rabbit “crashed” the Mad Tea Party and they destroyed his watch. I also was intrigued by the ending, when Alice could see herself sleeping through the keyhole while the Queen of Hearts and the other denizens of Wonderland were in hot pursuit. Those scenes have remained vividly in my mind ever since.

As for the 7-year cycle of theatrical releases, I know that I saw both “Alice” and “Dumbo” at various times in local movie houses, so despite their occasional exposure on television, they still were rotated into the cycle–at least by the 60’s and 70’s.

Also on a side note but worth noting–Walt Disney never lost an opportunity to include footage from “Fantasia” in the anthology series. Wherever he could work one in, one of the segments would pop up. Especially when it could be presented as an example of high art. Check out “An Adventure in Art” or “The Plausible Impossible.” (There are many more such instances.) These appear to be (successful) attempts to justify “Fantasia” which had been subject to scathing reviews. In my opinion, the film needed no justification–nor did “Alice.” Even at his most experimental, Walt Disney managed to produce extraordinary feats of animation which have stood the test of time.

@FREDERICK WIEGAND: Although Alice in Wonderland initially lost money at the box office, Dumbo was profitable in its original American release (though partly due to the fact it did cost much less than the features made around the same time). I assume it made it to TV since it was short enough to edit down into an hour-long slot, and because it had enough name recognition to draw viewers. I’ve often wondered what was missing from the edited version of Alice in Wonderland, though; did they just cut out entire sequences, and/or edit each of the sequences substantially?

Thanks! Totally forgot about the anniversary of Alice!

By the way Ginny Tyler is pictured in front of the later 1988 Gumby, which, of course, she had NOTHING to do with–she was in the 60s-70s ones, “dearie”..(a la her witch character..!)

Most of the versions of Alice In Wonderland I’ve seen tend to go too dark and sinister. Disney’s version, for all the liberties it takes and for how much it “Americanizes” aspects of it, comes closest to Carroll’s original tone in my opinion.

Another version I like is the Muppet Show episode with Brooke Shields. Especially their reenactment of “Jabberwocky”, which confounds even the performers. (Scooter: “Have you seen the scene? Even when you know what it is you don’t know what it is!”) Jim Henson was another master of “nonsense” – I’d say the equal of Carroll – whose work has rarely been equaled.

I took a voice-over course at Pasadena City College back in about 1984, and the instructor was Ginny Tyler! I had no idea about what her credits were then (the only role she mentioned in class was the girl squirrel in “The Sword in the Stone”). But boy, was she a delight to listen to! She would take a sentence, and say it back to us while putting emphasis on a different word each time, and thereby demonstrating that you could completely change the intention of the sentence with that one change. Since then, whenever I see her name or recognize her voice in a recording, I feel like, “Oh wow; that’s my teacher!”