This week’s breakdown goes into one of the finest Silly Symphonies!

Dick Huemer, an animator on this cartoon, stated to Joe Adamson, in later years, that had other animation studio produced Tortoise and the Hare during the ‘30s, the results would have been mundane—just numerous gags about running.

Huemer’s opinion definitely has some clout; other animation studios could deviate from Aesop’s fable, but, based on its concise nature, the additions are sufficient. For instance, the Hare rests while the Tortoise plods behind him but ends up oversleeping, resulting in his loss. In Disney’s version, this element is used only briefly, when Max Hare wakes up after Toby passes him, only to race past him moments later. In this version, too, the reason for Max Hare’s loss is clever: he proceeds to demonstrate his athletic prowess and speed—playing archery, baseball, and tennis by himself.

The Tortoise and the Hare was directed by Wilfred Jackson, regarded for the meticulous attention to detail he bestowed in his Disney cartoons. Jackson joined the staff as an assistant animator for Ub Iwerks on April 16, 1928, as the studio continued to produce the Oswald cartoons.

As the studio struggled with synchronization to sound for Steamboat Willie, Jackson’s musical upbringing benefitted Disney and his staff. He brought in a metronome and used it to plan the action of Steamboat in advance, before the music and animation began. Jackson continued to animate until he became a director on The Castaway, released in 1931. By that time, he oversaw the studio’s growth as it became more departmentalized—particularly story men and the layout department—by a large, assimilated staff. As time passed, their skill improved considerably in different ways, and the Silly Symphonies were a breeding ground for experimentation.

As the studio struggled with synchronization to sound for Steamboat Willie, Jackson’s musical upbringing benefitted Disney and his staff. He brought in a metronome and used it to plan the action of Steamboat in advance, before the music and animation began. Jackson continued to animate until he became a director on The Castaway, released in 1931. By that time, he oversaw the studio’s growth as it became more departmentalized—particularly story men and the layout department—by a large, assimilated staff. As time passed, their skill improved considerably in different ways, and the Silly Symphonies were a breeding ground for experimentation.

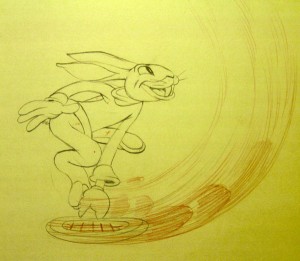

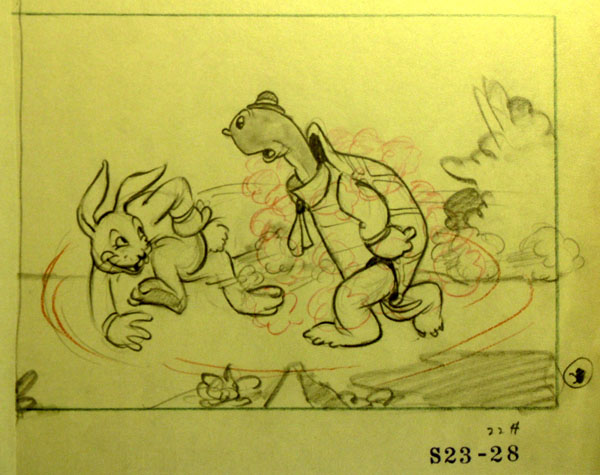

Max Hare (voiced by character actor Ned Norton) possesses speed so impressive that its sheer force un-roots trees from the ground and pulls the feathers from an observing crane. This type of extraordinary velocity, in which he crosses the screen in less than a second, was a novel and important concept for animation. Jackson appointed a bulk of Max Hare’s scenes during the race to Ham Luske, with Dick Lundy put to work on Toby Tortoise (voiced by Eddie Holden). Just as Luske’s poses and actions enrich Max Hare’s vain personality, Lundy’s animation of the amiable turtle is just as convincing. Toby is fairly reminiscent of Tex Avery’s Droopy—unassuming on the surface, but able to face humiliation with dignity.

Luske used his previous experience as sports illustrator for the Oakland Post-Inquirer for this cartoon. An athlete in his own right, Luske animated the boastful hare playing tennis with himself — a triumph in caricaturing movement. Max’s nimble, sporty actions seem realistic, but it amplifies to an improbable degree. Luske’s assistant, Ward Kimball, always strived to push Luske’s drawings further, as he would with his own animation. Another young artist blossomed under Luske’s tutelage. Eric Larson, credited with two scenes for Tortoise and the Hare, previously served as Luske’s assistant. Larson learned about the study of motion from Luske’s observations, since he applied the principles of animation outside the studio. For instance, the two played golf together and he taught Larson about anticipation (a specific action that anticipates what occurs next) before they went to putt.

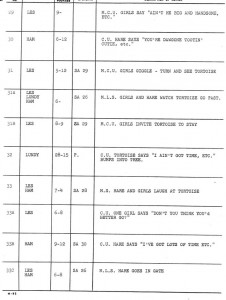

Les Clark, responsible for the schoolgirl rabbits that admire Max Hare, arrived at the studio before Jackson, in February, 1927. In his first six months, he served as a camera operator, then spent another six months as an inker/painter. He eventually became a full animator on The Skeleton Dance, the first Silly Symphony released.

Les Clark, responsible for the schoolgirl rabbits that admire Max Hare, arrived at the studio before Jackson, in February, 1927. In his first six months, he served as a camera operator, then spent another six months as an inker/painter. He eventually became a full animator on The Skeleton Dance, the first Silly Symphony released.

Clark’s scenes in The Tortoise and the Hare are clearly staged and easily communicated; traits no doubt inherited from Ub Iwerks’ facile drawing. A versatile draftsman, Clark could animate broad characters and those that demanded more delicate drawing; the latter being utilized in this cartoon. Like Wilfred Jackson, Clark’s presence coincided with the studio’s wide spectrum of animated projects throughout his career, which lasted almost fifty years. He retired from the studio in September, 1975.

Dick Huemer animates the final portion of the race with Max and Toby. Huemer peppers the climax with small details, more or less carried over from comic strips, like spark lines and droplets of moisture (Toby’s nervous sweating and Max’s farewell kisses, in particular). In his scenes, Huemer interprets Max’s speed much differently than Luske, but it’s absolutely fitting for the climax. The hare’s eagerness for victory makes his feet tread ground, lifting him up in the air. In addition, Max’s determined expression—with his thick eyebrows—is priceless. Huemer also contributes a nice touch as the hare receives his comeuppance. He nearly, but deservedly, burrows his head into the ground, as Toby wins by a neck.

The Tortoise and the Hare received an Academy Award for Best Animated Short for 1934, defeating Holiday Land (with Scrappy) and Jolly Little Elves, Charles Mintz and Walter Lantz’s first cartoons in color, respectively. This cartoon became a landmark of animation, influencing many studios to increase the timing in their gags. As a result, speed became an integral part of lauded series —the Fleischer Popeye cartoons, Shamus Culhane’s work at Lantz, the Warner Bros. cartoons, and, of course, the Hanna-Barbera and Tex Avery units at MGM.

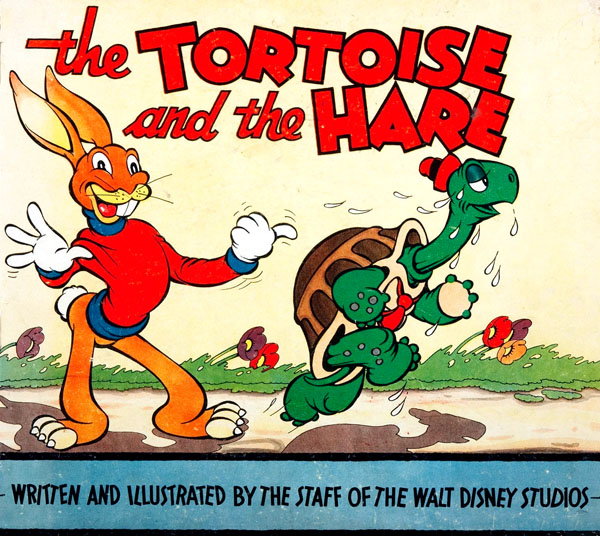

Max Hare’s impudence arguably generated the character of Bugs Bunny — a figure in the same mold, but handled with more subtlety and nonchalance. Bugs’ indifference is even tested in a series of cartoons—directed by Avery, Clampett and Freleng— based on the fable, with his opponent Cecil Turtle. Max Hare and Toby Tortoise were featured in the Silly Symphonies Sunday comic strip series entitled “The Boarding-School Mystery”—drawn by Al Taliaferro and written by Ted Osborne—published from December 23, 1934 to February 17, 1935. (You can see the complete story on Dave Gerstein’s marvelous book Mickey and the Gang.)

Max Hare’s impudence arguably generated the character of Bugs Bunny — a figure in the same mold, but handled with more subtlety and nonchalance. Bugs’ indifference is even tested in a series of cartoons—directed by Avery, Clampett and Freleng— based on the fable, with his opponent Cecil Turtle. Max Hare and Toby Tortoise were featured in the Silly Symphonies Sunday comic strip series entitled “The Boarding-School Mystery”—drawn by Al Taliaferro and written by Ted Osborne—published from December 23, 1934 to February 17, 1935. (You can see the complete story on Dave Gerstein’s marvelous book Mickey and the Gang.)

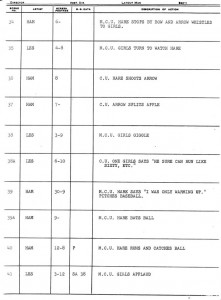

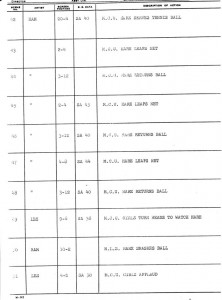

Presented here is an authentic draft of Tortoise and the Hare, instead of notes (or cutting continuities). It’s noted that the layout for this cartoon began in May 1934, and was completed by September. Jackson supplied different scenes for his animators to share—Luske on Max Hare and Lundy on Toby Tortoise — but the characters are only on-screen for a brief amount of time. In scene 7, Lundy animates both Max and Toby before the race, and the two are on-screen together for almost thirty seconds. There is no animator credited on the cheering crowd during the end of the race; the re-use of the same shot isn’t listed on the draft, but it could’ve been a late addition into the cutting. As Jackson recalled during a 1939 lecture, he attempted to fit the music of the rush to the finish line with quick cuts to Max and Toby. He re-inserted shots of the crowd to effectively bridge the musical phrasing of Frank Churchill’s “Slow But Sure,” (Toby’s theme) and the siren sound effect of Max’s manic momentum.

Hope you all enjoy this (Oscar-winning) breakdown video!

(Click on drafts below to enlarge)

(Thanks to Mark Kausler, Michael Barrier and Frank Young for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

Devon:

Definitely a classic! I felt sorry for Toby,but he handled the relentlss teasing very well! Max was one of the best animated speed characters I’ve ever seen! Thanks for sharing!

Exaggeration of a physical attribute for comic effect was already a cartoon staple by 1934 — it was the type of physical attribute and the way the Disney staff handled it that made this cartoon so important in this history of animation (i.e. — the Fleichers had been doing Popeye strength gags for a year by the time “The Tortoise and the Hare” came out which tied into his personality. But those didn’t require developing new techniques or faster timing in animation, but simply putting the character into outlandish situations against something/someone either very heavy or very powerful. They didn’t have to invent new animation processes to get the point across, as Jackson and his crew did).

It’s always a treat to watch this cartoon. Its use of color is very effective. I always enjoy Toby’s retractable/expandable limbs. And Max Hare has a natural charm that makes him appealing even when he’s being a jerk.

Fascinating to see how the various animators handled each situation. Especially of interest to me are the frames where one animator did one character and another handled the others. There is a lot of consistency from animator to animator. Ham Luske did a great job with Max, and Dick Lundy seems very inspired with Toby. The Disney guys really worked as a team to make a competent, well-crafted cartoon that is still enjoyable and relevant today.

Nice job, Devon! That’s Milt Schaffer animating the cheering crowd at the end, as he had previously animated the crowd in the bleachers in sc 3. Schaffer had demonstrated his facility with crowd scenes around this time and soon found himself typecast, routinely assigned LOTS of crowd scenes. He had cause to regret the impression he’d made, for those crowd scenes were tedious, time-consuming assignments. (By the way, those dates in the upper right-hand corner of the draft typically indicate the dates of layout, not animation.)

Thanks, J.B.! Got your PINOCCHIO book, by the way. Phenomenal job!

“”In scene 7, Lundy animates both Max and Toby before the race, and the two are on-screen together for almost thirty seconds””

In fact, Lundy animates *both* the main characters in all the scenes before the race starts. Were these scenes assigned before they decided to cast the animators by character, or were they freeing up Ham Luske for the later scenes, or what?

“Toby Tortoise and the Hare”, what an odd title for that picture book. It’s like Toby Tortoise was a familiar hero and Max Hare was his antagonist of the week.

Yes, the Pinocchio book is great! I’ve always had a special interest in the making of that film – in fact it was reading about the animator casting of “Pinocchio” in Christopher Finch’s “Art of Walt Disney” that first piqued my interest into animation history of this kind.

JB, do you know anything about the other S(c)haf(f)fer – Armin Schafer? He’s credited (“Armin S.”) on the Pinocchio draft, as one of many animators on a complex scene in sequence 10.7 of the raft escaping Monstro? There was a big discussion on Mark Mayerson’s draft a long while ago about whether the “Shafer” on the “Mickey’s Birthday Party” draft was Milt or Armin, with people saying it was Armin who animated on “The Country Cousin” (it was Milt, right?) Also, there’s a mention on the “Night on Bald Mountain” draft of an effects animator named “Shaffer”.

You seem very knowledgeable about the studio’s history, I wonder if you can shed any light on this?

Thanks to you, Devon — and, in case I haven’t mentioned it before, thank you for doing these breakdowns. I really like the way you’re covering such a wide cross-section of classic cartoons.

Hi, John V — and sorry, I’m having a delay effect here. Thank you for your comments. No, I really don’t know too much about Armin Schafer. You’re right, Milt Schaffer did animate on “Country Cousin” — but whoever was the “Shafer” who animated on “Mickey’s Birthday Party”, I’m pretty sure it wasn’t Milt. He transferred to the story department ca. 1937, and was still there at the time of the strike in 1941, around the time “Mickey’s Birthday Party” was in the works. Schaffer wasn’t one of the strikers, but he was one of the people laid off after the strike. He went to the Lantz studio for several years, then came back to Disney — always in story.

Devon, this is very good indeed. It’s difficult when looking at something that was very influential & much imitated to see it the fresh way audiences saw it at the time. I remember that when the Museum of Modern Art did a huge show on Disney, they devoted an exhibit just to this one cartoon. Some of the same ground was covered that you cover here. Did you see it? Of course not, young man! This was in the late ’70s or early ’80s — and you weren’t born yet! 😉

Don’t forget “Toby Tortoise Returns” (1936), for showcasing just how wild and experimental the Disney studio was branching out during the 30!

Oddly enough, “TOBY TORTOISE RETURNS” was the only one of the two cartoons that I’d actually physically saw and I believe that was part of “MOUSE FACTORY”. Interesting that this, the second of the TORTOISE AND HARE cartoons put the two in a boxing ring, a move that the other studios would try at various times, especially Famous with TOMMY TORTOISE AND MOE HARE in a cartoon called “RABBIT PUNCH”, the same title used for a BUGS BUNNY cartoon that also had Bugs thrown, literally, into the boxing ring.

I still have my copy of the Tortoise and the Hare book from the 30’s (though, sadly, colored on some of the pages. . I love it still and saw the cartoon over and over. Great artists who created something quite fantastic for a little girl, and still does.