Legal complications following the release of Timothy Dalton’s License To Kill (1989) saw the James Bond movie franchise go on hiatus for six years. The movie series finally returned with 1995’s GoldenEye and Pierce Bronson as the new Bond.

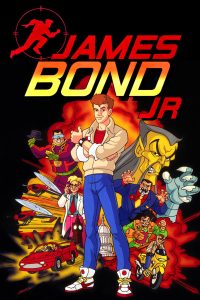

During this six year period emerged one of the lesser loved entries in the Bond franchise’s history: the animated series James Bond Jr. that debuted September 1991. It was a 65 episode syndicated series that only ran for one season.

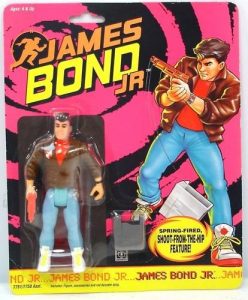

The copyright holder Eon Productions would prefer the show be significantly downplayed even though it spawned six junior novelizations by writer John Peel, twelve Marvel comic book issues, a board game, die-cast vehicles, action figures, coloring books, a Nintendo videogame and more.

Kevin McClory who owned certain rights to Bond announced in a February 10th, 1988 issue of Variety that he was working to produce an animated James Bond series called James Bond vs. S.P.E.C.T.R.E., to be produced by an unnamed Dutch animation company.

Andy Hewyard who was the CEO of DIC was approached by Michael Wilson and Barbara Broccoli of Eon Productions who were responsible for the James Bond films. They wanted to undercut McClory’s efforts at an animated series, keep the Bond franchise prominent during the legal situation that prevented a new film, and get involved with the lucrative animation syndication market that spawned merchandise sales.

A preliminary deal was reached with Eon, DIC, Hasbro (as the toymaker) and Claster Television (Hasbro’s distributor of children’s programming). However, there were several stipulations. Eon would own the copyright on all the material generated and Eon would hire and supervise the writing.

A preliminary deal was reached with Eon, DIC, Hasbro (as the toymaker) and Claster Television (Hasbro’s distributor of children’s programming). However, there were several stipulations. Eon would own the copyright on all the material generated and Eon would hire and supervise the writing.

Eon was aggressive in protecting the franchise and wanted it limited to just elements from the movies and not the original Fleming novels. They wanted to avoid making it a young James Bond to avoid any inconsistencies or any limitations being established going forward.

Robby London who was Executive Vice President in charge of creative affairs at DIC Entertainment was waived his exclusivity to DIC and negotiated a separate deal with Eon to have a work-for-hire contract to develop the show bible and a few sample stories, some of which like Eiffel Missile, were later used in the series but fleshed out by other writers. He even received a shared “created by” screen credit on the entire series but his name was misspelled as “Robbie”.

For reasons that are unclear, after the story bible was completed and approved, Eon decided to move the project from DIC to Murakami-Wolf-Swenson studios that was enjoying huge success at that time with the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles property and who were looking to expand into the European market. MGM Television was also involved.

While the books by Ian Fleming make it clear that James Bond is an only child with no living relatives, the premise of the series was that he had a seventeen year old nephew who was named after him.

The character was old enough to handle the dangerous adventures but still young enough to relate to a young audience. Eon did not want to imply that James Bond had a wife, an ex-wife or a child out of wedlock so the relationship was intentionally unspecified and vague.

While it was discussed, Bond himself never appeared in the series although he was mentioned even in the opening theme song itself: “Bond, James Bond Jr., No one can stop him but S.C.U.M. always tries, young Bond cuts through each web of spies, he learned the game from his uncle James, now he’s heir to the name.”

While it was discussed, Bond himself never appeared in the series although he was mentioned even in the opening theme song itself: “Bond, James Bond Jr., No one can stop him but S.C.U.M. always tries, young Bond cuts through each web of spies, he learned the game from his uncle James, now he’s heir to the name.”

James Junior (voiced by Corey Burton) attends the boarding school Warfield Academy because his father (a linguist) and his mother (an archaeologist) are “missing” and assumed to have been captured by S.C.U.M. (Saboteurs and Criminals United in Mayhem) and the original intent for the various missions was to try to find his parents.

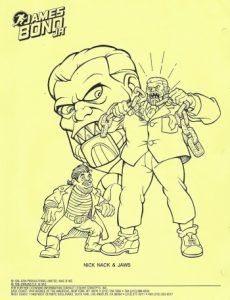

One of Bond’s most famous enemies, Jaws, was a recurring henchman and was often paired as a bickering duo with Nick Nack, the minion from The Man With The Golden Gun. Auric Goldfinger appeared in several episodes and has a daughter called Goldie Finger who shares her father’s lust for gold.

Goldfinger’s henchman Oddjob (originally meant to be the son Oddjob Jr.) also returned with his deadly hat but was given a strange makeover with a purple jumpsuit, sunglasses and a large gold necklace with his initials like Mr. T. Doctor No was also given a makeover with green skin perhaps to de-emphasize his Asian background like was done with similar characters on other animated series. New villains were introduced as well.

While Bond was a lone wolf, James Junior was helped by a team to make him more accessible to an audience. The team included among others Horace ‘I.Q.’ Boothroyd III (voiced by Jeff Bennett) who is the grandson of Q (007’s armorer) and is a scientific genius who also creates gadgets; Tracy Milbanks (voiced by Mona Marshall), daughter of Bradford Milbanks, who is the headmaster of Warfield; and Gordon “Gordo” Leiter (voiced by Jan Rabson), the son of 007’s C.I.A. associate and friend Felix Leiter who is the “strong fist” of the group.

While Bond was a lone wolf, James Junior was helped by a team to make him more accessible to an audience. The team included among others Horace ‘I.Q.’ Boothroyd III (voiced by Jeff Bennett) who is the grandson of Q (007’s armorer) and is a scientific genius who also creates gadgets; Tracy Milbanks (voiced by Mona Marshall), daughter of Bradford Milbanks, who is the headmaster of Warfield; and Gordon “Gordo” Leiter (voiced by Jan Rabson), the son of 007’s C.I.A. associate and friend Felix Leiter who is the “strong fist” of the group.

James Junior was primarily based on actor Roger Moore’s intrepretation of the character.

Bill Hutten and Tony Love produced and directed the series at a demanding pace of completing all sixty-five episodes in twelve months. Hutten oversaw script supervision, voice actor selection, main character designs as well as other artwork, catching last minute mistakes and working with Eon’s on-site contact, John Parkinson, whose role among other things was to not turn the characters into more adult-oriented versions and keep them separate from the film franchise.

The female characters could not be drawn too sexily and James Jr. could not talk to them in the same manner as his uncle. References to drinking were not allowed. James was not to be called “007 Jr.” although the assumption was that the character would grow up to be like his more sophisticated and experienced uncle.

Michael Wilson, Barbara Broccoli and “Cubby” Broccoli visited the studio to watch sixty to seventy people working on the production and then attended a recording session. Cubby mentioned he had no idea it took so much to produce a cartoon film. Wilson and Barbara Broccoli later held a “wrap party” at the end of production for many of the people who had worked on the series.

Jack Mendelsohn was one of the four story editors for the series and loved having writers include dialog like when James Jr. and IQ emerge from a cage that was about to plunged into lava, “At least we were just shaken, not stir-fried” or when a guard slips on some oil “looks like we gave him the slip”. Like the other story editors he often had to do some occasional re-writing.

The episodes followed a standard format of a pre-title sequence, a situation that James Jr. must handle, a scene where he is trapped and must use his wits and perhaps a gadget, a larger-than-life villain, lots of action and a teen version of a Bond woman all in just twenty-two minutes.

Eon Productions and most Bond fans do not consider anything in the animated series as canon but simply an aberrant tangent that while briefly released on a series of VHS tapes in 1992 has never been rerun on television or offered on DVD, BluRay or any streaming service.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

I was a baby when the first James Bond movie came out, but I was over forty before I saw any of them. By then I had read most of the Ian Fleming novels, having picked up Goldfinger for a few cents at a garage sale on a whim and discovered much to my surprise that I really enjoyed it. Eventually I decided to watch all of the Bond films in order of release — they were all readily available at the local video store — but my interest flagged early on, and I gave up after Moonraker. I guess my childhood exposure to Maxwell Smart, Secret Squirrel and Lancelot Link has rendered me incapable of taking the espionage genre seriously. I don’t recall hearing about James Bond Jr. during its original syndication run, and it probably wouldn’t have interested me if I did.

I noticed in the closing credits that Dan Povenmire, co-creator of Disney’s “Phineas and Ferb” as well as the voice of Dr. Doofenshmertz, did storyboards for James Bond Jr.

By the way, it’s Pierce Brosnan, not “Bronson”, even though practically everybody pronounces it that way.

All 65 episodes of “James Bond Jr.” are available for viewing on YouTube. I’ll have to check it out. Will I get as far into it as I did with the feature films? We’ll see.

This is another one of those series where no overseas studio is listed in end credits, even though quite a few worked on it. Much like seasons 3-7 of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, it would be nice if that info ever surfaced- i.e. which studios worked on which specific episodes. But it would probably have to come from Murakami-Wolf-Swenson itself, and I doubt they still have that info. It very well might be lost to time, unfortunately.

I think you are getting into the real down and out dregs of the business here, Jim. You have covered better material than this, thank goodness.

Typical ’90s pretty boy. The love child of Ben Affleck and Brad Pitt hits Toontown.

“Michael Wilson, Barbara Broccoli and “Cubby” Broccoli visited the studio to watch sixty to seventy people working on the production and then attended a recording session.”

I’m sorry, Jim, but I don’t think that this was true. Most of the pre-production was freelance work and the show was definitely animated somewhere in Asia. Recording, possibly, but “sixty to seventy people,” I seriously doubt. Perhaps Hutton and Love asked all their friends to show up and fake that they were working to impress the Broccolis.

Hey, that’s what put Filmation on the map.

Dear Jim,

I would like to see more about obscure cartoons like “Starla and the Jewel Riders”, “Skysurfer Strike Force” et cetera.

I can tell you a few things about “Starla and the Jewel Riders”. For one thing, that was the title of the international version of the series. In North America, it was known as “Princess Gwenevere and the Jewel Riders”. The international version also had a different (and, in my opinion, inferior) musical score, although it had the same theme song, rerecorded to match the change in title. Otherwise the two versions are much the same, and I have no idea why the main character’s name was changed for overseas distribution. The international version is the one available on most streaming services, but complete episodes of both versions can be found on YouTube.

Series creator Robert Mandell, who had previously created “Adventures of the Galaxy Rangers”, served as head writer. He was supported by a team of interesting and accomplished writers who have otherwise written very little for animation. James Luceno, who wrote two episodes, is a best-selling author of reference books about, and novels set in, the Star Wars universe. Science fiction and fantasy horror writer Christopher Rowley wrote six scripts, and renowned children’s book author Mary Stanton wrote three. Then there’s Linda Shayne, with a pair of episodes, who has had a varied career as an actress, writer and director in film and television. But I’ll always remember her as the co-writer and star of the 1980s sex comedy “Screwballs”, in which she played a character named “Bootsy Goodhead” and had several nude scenes.

Voice director Peter Fernandez, who voiced ancillary characters like Grimm the dragon, was a pioneer in the dubbing of Japanese anime, having played Speed Racer (and his brother, Racer X) in the eponymous TV series. He also adapted many of the Speed Racer scripts and wrote the English-language version of the theme song. Another Speed Racer connection: Corinne Orr, who had played Trixie in that series, was the voice of both good Queen Anya and evil Lady Kale in “Jewel Riders”.

The actresses who played the Jewel Riders all had strong backgrounds in musical theatre. The original Princess Gwenevere/Starla, Kerry Butler, left at the end of the first season when she was cast as Belle in the Toronto production of Disney’s “Beauty and the Beast”. She was replaced by Jean Louisa Kelly, who had been in the original Broadway production of Stephen Sondheim’s “Into the Woods” when she was still in high school. Laura Dean, who voiced Tamara, had sung in several productions of the New York City Opera and later had a recurring role on the sitcom “Friends”.

I saw “Princess Gwenevere and the Jewel Riders” during its original run on an independent UHF station as part of a Sunday morning programming block of odds and ends, and while the animation had the same shortcomings as that of every other syndicated series at the time, I found myself captivated by the stories and the characters. The artwork was quite beautiful, especially the backgrounds, and the show made good use of computer effects back when the technology was still in its infancy. It was one of the first, and still one of the very few, original animated series in the magical girl fantasy format to be produced in the United States. It also seems to have had a strong influence on the French anime series “LoliRock”, in the appearance and personalities of its three leading characters as well as the magical Oracle Gems that control the fate of the universe.

Sorry — I’ve wandered a long way from “James Bond, Jr.”, haven’t I?

Wow, the guy who did Galaxy Rangers did Princess Gwenevere. What a drop in quality. But hey, a show is a show.

I totally remember watching this show ( I watched everything back then). It was always a disappointment. I wished they had pushed it like other action shows, but was always too doopy to be more than just mildly interesting. Also seemed to be part of the long tread of “kiddizing” an IP Muppet Babies, Flintstones Kids, etc.