Author’s Note: As you may know, I have shared many animator breakdown videos on my Patreon account, ranging from Warner Bros. to Disney, with an occasional animator draft from Walter Lantz’s studio. If you would like to see these, consider subscribing to the page — this link will redirect you to the animator breakdown videos.

In my debut post for Cartoon Research, I neglected to mention where these “animator breakdowns” originated. Back in 2006, Thad Komorowski presented a blog that offered insight into which animators were responsible for their scenes in an animated short cartoon released during the Golden Age. This information was informed by experts in the animation field with a keen eye for animators’ styles, such as Mark Kausler, Mike Kazaleh and Greg Duffell. When such posts became infrequent, I thought it best to continue the tradition of sharing rare animator drafts to devoted animation enthusiasts.

During production on a short or feature, directors used a sheet, or a series of sheets, that listed animators with their designated shots in order to calculate the total screen footage. Concurrent with Thad’s blog, animator/historian Hans Perk launched his own, sharing production materials from Walt Disney’s studio sourced from his own collection.

The animated films of Walt Disney, both shorts and features, are amply documented, since records are housed within their Archives. Non-Disney studio drafts, particularly Warner Bros., are more difficult to obtain. In the late 1970s, the late Dave Butler researched and interviewed Bob McKimson for a book that never materialized. During their interaction, Dave acquired many artifacts, including a cache of animation drafts saved by McKimson, which have been circulated and photocopied by a few animation historians and scholars over time. Bob Clampett, known for saving a wealth of material from the studio, housed a similar collection; two animation drafts from his archives (Get Rich Quick Porky and A Tale of Two Kitties) have been shared on Cartoon Research, but the rest is still unknown as of this writing.

What of the other principal directors like Chuck Jones, Friz Freleng or Frank Tashlin? With the exception of Chuck Jones’ directorial debut The Night Watchman (1938), it can be assumed these materials were ultimately destroyed. In addition, author/historian Kurtis Findlay found only a few such materials in Jones’ archives, mainly from projects released in the 1960s. A few accounts recalled that the Warner Bros. animation department kept an immense archive in a warehouse building with its production materials housed and catalogued floor to ceiling. When Kinney National acquired Warner Bros. from Seven Arts sometime around 1969, their theatrical cartoons were diminishing. After a while, Kinney National decided to destroy its inventory to save storage costs. Of course, not every piece was a casualty of this liquidation—a large amount of animation drawings, layout drawings, background paintings, preliminary lobby cards and model sheets, among others, still survive from the studio today.

What of the other principal directors like Chuck Jones, Friz Freleng or Frank Tashlin? With the exception of Chuck Jones’ directorial debut The Night Watchman (1938), it can be assumed these materials were ultimately destroyed. In addition, author/historian Kurtis Findlay found only a few such materials in Jones’ archives, mainly from projects released in the 1960s. A few accounts recalled that the Warner Bros. animation department kept an immense archive in a warehouse building with its production materials housed and catalogued floor to ceiling. When Kinney National acquired Warner Bros. from Seven Arts sometime around 1969, their theatrical cartoons were diminishing. After a while, Kinney National decided to destroy its inventory to save storage costs. Of course, not every piece was a casualty of this liquidation—a large amount of animation drawings, layout drawings, background paintings, preliminary lobby cards and model sheets, among others, still survive from the studio today.

Now, onto the cartoon!

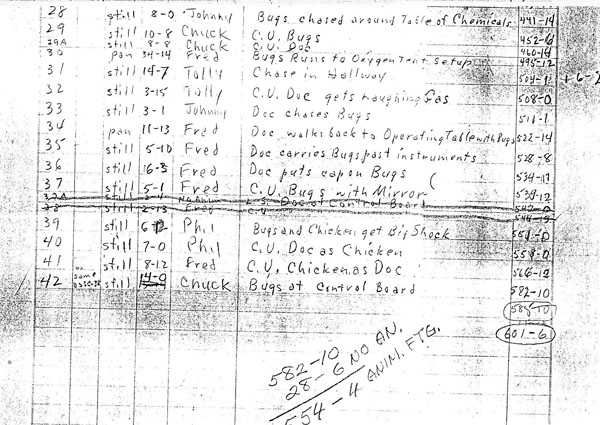

Under its working title “The Rabid Rabbit,” Mel Blanc recorded his vocals for Hot Cross Bunny on June 15, 1946. During the film’s production, a few changes in Warner Bros.’ animation department occurred. As seen under the main opening titles, three mainstay animators—Manny Gould, Charles McKimson and Phil De Lara—are credited for their work. Indicated by various production drafts detailing films released before and after this production, this is the last known Warners cartoon with animation by Isadore (Izzy) Ellis. In the late 1930s, Ellis joined Leon Schlesinger’s studio as one of the main animators in the “Katz unit,” a separate studio run by producer Schlesinger’s brother-in-law Ray Katz located in Beverly Hills, which produced the black-and-white Looney Tunes, usually with Bob Clampett as director. A presumed departure for more lucrative work at another studio might account for his lack of credit, but his whereabouts are unclear.

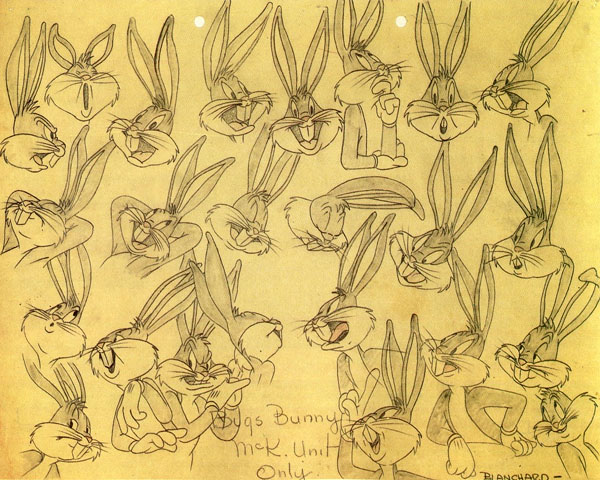

Model sheet of Bugs, with McKimson’s character layouts from this cartoon and A-LAD-IN HIS LAMP, directly copied/traced by assistant animator Jean Blanchard. Because of her name inserted on the sheet, this design of Bugs is misattributed to Blanchard.

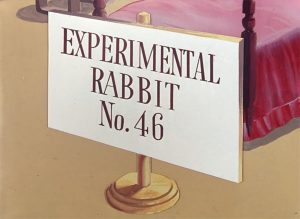

In the cartoon, Bugs is subject to a scientific experiment that would transfer his personality into a chicken, and vice versa. This occurs inside of the medical building of the Paul Revere Foundation, with a touch of dark humor for its slogan derived from the Longfellow poem, “Hardly a man is now alive.” Bugs, innocent to the purpose of his stay, reclines comfortably in bed, enjoying “the life of Riley.” The production draft denotes a few scene additions that display the advantages of his pampered surroundings—which also include pin-ups of female rabbits—shown in static background paintings. Scene 6F does not list an animator, but it seems to be a continuation of scene 6, credited to Charles McKimson. After requesting a rabbit nurse of all accommodations, Bugs instead must undergo a physical examination. His response to the French physician who is heading the experiment—“Oh, Doctor!”—is an amusing double entendre as Bugs coquettishly bats his eyelashes and tucks his legs under the covers.

What follows is a brief series of gags involving Bugs’ examination, mostly animated by Russian-born Anatole (Tolly) Kirsanoff. Though the doctor appears much taller than the experimental rabbit in previous scenes, there seems to be an issue with size relation in scene 11, where he appears to be almost shorter than Bugs (an inconsistency will continue throughout the cartoon). The sequence concludes with a great capper as Bugs reads an eye chart—including the microscopic bottom line of the union disclaimer!

Like Izzy Ellis, Hot Cross Bunny is also the last known cartoon that Kirsanoff animated for Warners. He worked as an in-betweener at Walter Lantz’s studio around 1938 where he was given the nickname “Jolly Tolly.” He left Lantz’s studio, joining the “Katz unit” by August 1939 as an assistant animator and was promoted to full animator by the fall of 1944. However, Kirsanoff never received credit for his work. He moved to UPA by 1948, indicated by a staff photograph where he has been identified.

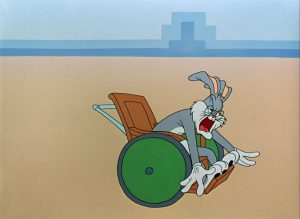

Manny Gould’s animation dominates many of the scenes that constitute the middle of the cartoon. As Bugs is escorted by wheelchair to the operation theater, he is instantly struck by the vast audience of doctors and assumes the role of a stage theater performer. In a long stretch of footage by Gould, Bugs does an impersonation of Lionel Barrymore, where several references to his storied career are evoked. Barrymore starred in a radio program entitled Mayor of the Town, which debuted in 1942 and was still broadcast during the cartoon’s production; it ended in July 1949. He ends the performance with a nod to his Dr. Gillespie character from the series of Dr. Kildare films (1938-42), which later spun off into Gillespie’s own movies (1942-47). As for the utterance of “Gentlemen of the jury…” it might be an allusion to the alcoholic defense attorney Barrymore portrayed in A Free Soul (1931), which earned him an Academy Award.

Manny Gould’s animation dominates many of the scenes that constitute the middle of the cartoon. As Bugs is escorted by wheelchair to the operation theater, he is instantly struck by the vast audience of doctors and assumes the role of a stage theater performer. In a long stretch of footage by Gould, Bugs does an impersonation of Lionel Barrymore, where several references to his storied career are evoked. Barrymore starred in a radio program entitled Mayor of the Town, which debuted in 1942 and was still broadcast during the cartoon’s production; it ended in July 1949. He ends the performance with a nod to his Dr. Gillespie character from the series of Dr. Kildare films (1938-42), which later spun off into Gillespie’s own movies (1942-47). As for the utterance of “Gentlemen of the jury…” it might be an allusion to the alcoholic defense attorney Barrymore portrayed in A Free Soul (1931), which earned him an Academy Award.

However, the consultation of “sourpuss doctors” is not impressed, as indicated by a still background of their grimacing faces, used three times in the cartoon. Bugs remarks the crowd is nothing like “St. Joe” and there is a brief introspective moment where he reminisces about the adoring crowd there. This was a reference to a line on The Jack Benny Program, which Benny repeated on several of the shows. Evidently, Benny was a success during his time in vaudeville at the town of St. Joseph, Missouri above others.

After a magic act involving a top hat fails to generate applause, Bugs dons the hat and does a soft-shoe dance, animated by Fred Abranz; like “Tolly” Kirsanoff, Abranz was never credited for his animation at Warners. This sequence is a direct lift (in animation and Carl Stalling’s original “showstopper” cue) from Friz Freleng’s Stage Door Cartoon (1944). Another film in production around the same time as Hot Cross Bunny used this routine to greater effect: Bugs Bunny Rides Again (1948), also by Freleng.

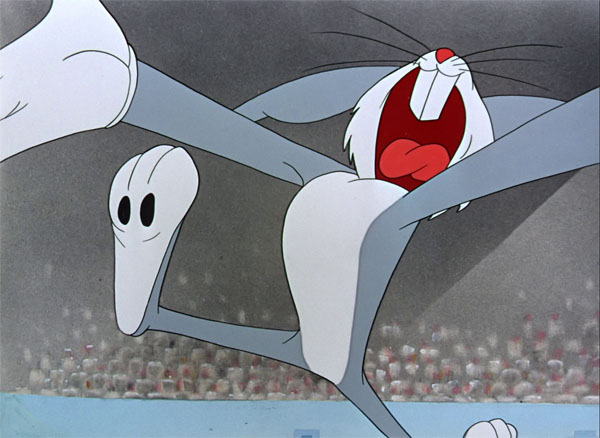

Still faced with an indifferent audience, Bugs tries once more with an “all-out” job. In one of Gould’s finest scenes as an animator, he does a scat-singing performance, a la Danny Kaye in his “Melody for 4-F” song number, originated in the MGM musical Up in Arms (1944). Daffy Duck had done a similar routine, dressed as “Danny Boy,” in Bob Clampett’s Book Revue (1946). In this version, Gould accents each last note with Bugs bringing his upper body (and his backside in one occurrence) close to the camera. His excessive performance is cut short when the physician carries him away and subdues him with a mallet. Before the experiment can be executed, Bugs takes on the role of motor-mouthed hot dog vendor at a sporting event, animated by Izzy Ellis. Perhaps, since he failed as a stage actor, he’ll succeed at a menial occupation, though he still takes pride in it.

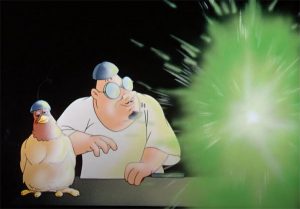

Bugs is struck with a mallet a second time, and the doctor is ready to begin the experiment to switch his characteristics into a chicken. As he regains consciousness, Bugs overhears these intentions and runs off, leading to a chase into the laboratory. A few scenes later, as animated by Fred Abranz, the doctor sprays laughing gas on Bugs and it takes immediate effect, as the helpless rabbit is carried back to the operating table. The doctor places the helmet on Bugs’ head and he flips the switch, displaying some remarkable effects animation of airbrushed electrical sparks. Somehow, in this same shot (animated by Phil De Lara), the doctor now has a helmet on his head, even though throughout the cartoon, it is established two subjects—with the same number of helmets—are intended for this experiment. This oversight puts a damper on the finale of an otherwise energetic and appealing cartoon.

The musical score for Hot Cross Bunny was recorded sometime around July 1947, with its ASCAP cue sheet approved a few months later on October 21. Carl Stalling incorporates Ella Fitzgerald’s swing rendition of the old English nursery rhyme “The Muffin Man”—popularized around the early 1940s—under the opening titles. The introductory scenes of Bugs lounging in bed are accompanied by Gus Kahn and Walter Donaldson’s “Carolina in the Morning,” which made its debut in the Broadway revue The Passing Show of 1922. As Bugs enjoys the luxury of being escorted down the corridor by wheelchair, Stalling uses a more recent tune, the Oscar-nominated “Some Sunday Morning” (Ray Heindorf/M. K. Jerome/Ted Koehler), introduced in the 1945 WB Western film San Antonio. During Bugs’ magic act, Johann Strauss’ “Frühlingsstimmen” (or “Voices of Spring”) plays in the underscore—a tune well fitted to his performance.

The musical score for Hot Cross Bunny was recorded sometime around July 1947, with its ASCAP cue sheet approved a few months later on October 21. Carl Stalling incorporates Ella Fitzgerald’s swing rendition of the old English nursery rhyme “The Muffin Man”—popularized around the early 1940s—under the opening titles. The introductory scenes of Bugs lounging in bed are accompanied by Gus Kahn and Walter Donaldson’s “Carolina in the Morning,” which made its debut in the Broadway revue The Passing Show of 1922. As Bugs enjoys the luxury of being escorted down the corridor by wheelchair, Stalling uses a more recent tune, the Oscar-nominated “Some Sunday Morning” (Ray Heindorf/M. K. Jerome/Ted Koehler), introduced in the 1945 WB Western film San Antonio. During Bugs’ magic act, Johann Strauss’ “Frühlingsstimmen” (or “Voices of Spring”) plays in the underscore—a tune well fitted to his performance.

Hot Cross Bunny was released two years after its initial voice recording session on August 21st, 1948. The film was re-issued under the “Blue Ribbon” banner a decade later—without the usual “Bugs Bunny in” title card—on November 21st, 1959. Recently, a newly restored version released on streaming services and available on the Bugs Bunny 80th anniversary Blu-Ray, retains the main titles from its original 1948 release.

(Thanks to Jerry Beck, Mark Kausler, Keith Scott, Andrew Gilmore and Greg Duffell for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

Thanks for an excellent breakdown, and especially for shining a light on the uncredited animators Ellis, Kirsanoff and Abranz. I love McKimson’s early Bugs Bunny cartoons!

The ominous chords heard over the exterior shot of the hospital at the beginning of the cartoon come from the opening bars of Felix Mendelssohn’s Overture to “Ruy Blas”, a play by Victor Hugo. Mendelssohn composed the overture in about three days as a commission from a theatre company, despite the fact that he hated the play, a very violent Spanish tragedy. In fact, one could say that by the time the final curtain falls on “Ruy Blas”, “Hardly a man is now alive.”

Also, while Bugs is under the influence of the laughing gas, the orchestra plays “Laugh, Clown, Laugh”, at a faster tempo than one would normally sing it.

According to their autographs, the pin-up bunnies on the wall are May (on the left), Bea (on the upper right), and Chloreen, lying prone on the beach. Funny, you’d think Chloreen would be in a swimming pool….

this cartoon was a plot device in Tiny Toon Adventures’ “Prom-ise Her Anything”.

Never knew about the planned book about McKimson in the ’70’s. I wonder why it was aborted.

Another well done breakdown, Devin! I, too, love McKimson’s Bugs. He always gave him a little pot belly which i think made him more relatable.

Good work, Devon!

The DR. KILDARE series was over for the movies, but audiences at the time would have been freshly reminded of the series, as it was recreated on radio for a series at the time the cartoon was made – by Lew Ayres and Lionel Barrymore. I think it lasted for about two years. MGM apparently did this with some of their film series, like CRIME DOES NOT PAY – which also was a syndicated radio series. One episode is noteworthy to me, where Bela Lugosi plays a crazed arsonist, called “Gasoline Cocktail’ (c. 1949).

Hey, can anybody out there find some proof that Ford Beebe, Jr. – who worked at Disney’s for years – did uncredited work as an “Assistant Director” on BARBER OF SEVILLE (1950)?

When I saw the Abranz credit on the tap dancing scene, I immediately thought that McKimson had handed him Chiniquy’s animation to adapt and redraw from and you provide compelling evidence of that. It is an interesting recognition of the fact that Bugs Bunny was drawn in many different ways in the same era, known to the directors at the studio at the time. Fred Abranz was an assistant animator officially, I would assume. That McKimson would assign quite a few scenes to “Tolly” and Abranz indicates to me that to in order to attain the level of perfection seen in the animation of these cartoons, the main animators were struggling to make the footage quotas. Regarding “Tolly”, I always thought the eye chart scene was animated in an unfamiliar way.

Excellent work, Devon. One clarification: I believe the black and white division, set up by Leon Schlesinger in 1937, was only based in Beverly Hills for the two cartoons that Ub Iwerks was involved with. Jones and Clampett were at that studio as Schlesinger’s people in an overseeing role. Soon they and some of Iwerks people moved back to the Warner Bros. lot in Hollywood where Schlesinger’s cartoon studio was based, and Ray Katz Productions – essentially Clampett’s unit doing the b&w Porkys – had a wing there. I have no idea when the Katz business name ended officially but it doesn’t seem to be mentioned after 1941 (that year Robert Bruce was in a radio casting book and one of his credits mentioned Cartoons: for Schlesinger, Katz & Walter Lantz).

I’m glad for the late Jean Blanchard’s sake that that model sheet of Bugs Bunny attributed to her was a bum rap. That’s got to be the most disagreeable-looking Bugs: pudgy, eyes too small, nose too big, lower lip too prominent. Even the 1950s tall-thin-man-in-a-rabbit-suit Bugs is preferable. “Hot Cross Bunny” is a fun cartoon, though.

A real “tour de farce” from start to finish.

I’d much rather watch McKimson’s sassy, unpredictable takes on Bugs than the same old Elmer Fudd and Yosemite Sam match ups from Jones and Freleng.

I love the unpredictability of McKimson’s Bugs Bunny cartoons, but Jones and Freleng did many spectacular Bugs Bunny cartoons. Freleng’s Bugs Bunny vs. Yosemite Sam cartoons in particular never stop being hilarious. High Diving Hare always cracks me up, it’s perfection!

I really hope that you upload your animator breakdowns from Patreon on here one day.