As I’m sitting here doing much overdue maintenance on archive materials on the 20-some hard drives currently occupying this current desk area, I’m struck by the temporariness of all this more recent media. It isn’t as if I haven’t known this before, but with the great gift of having so much material gathered, organized and archived comes the inevitable realization that it’s pretty difficult to make sure all of this stays intact and usable. In the digital age the problem is really the same as it has always been: how do you store all this stuff in a way that make sure it gets hurt as little as possible.

Nearly every film collector faces this same challenge, and the inevitable heartbreak of just not being able to preserve the stuff in the condition you received it in for one reason or another. The bigger the collection, the harder the challenge is. I’m been lucky enough to lose every little in the way of digital files over the years, but I’m also now intrinsically aware that my backup dvds and hard drives all have issues related to their inevitable demise. It means that something needs to be done to back things up, and then, over time, to keep backing up the back ups so nothing is lost. The problem really come down to expenses on that end of things. I wonder if the lost material of the future is all going to need to be attempted to retrieve by opening up hard drives with non-working motors…

Steve Stanchfield (from behind) overseeing new 2K scans of Bray films in late 2015

It’s another big dubbing and packing week as I start school for the year, but happily my schedule allows full days to spend just Thunderbeaning. Final cleanup and color correct work is taking place on the material we’re fixing up for Arnold Leibovitz’s Puppetoon Movie 2 Blu-ray set. Amazing stuff. The Noveltoons Blu-ray isn’t back from replication quite yet, but chances are it will be by this time next week. The majority of the Flip the Frogs are cleaned up and looking very spiffy, and the set is waiting for some sound work and getting back to bonus features. Rainbow Parades Volume 1 as well as several other less-involved sets are getting pretty close to being finished, and the special sets are going that direction quite well too. We’ve started dubbing Missing Links as well as a few others, and I’m hoping to get the Terry/Lantz/Famous one done next week, and if all goes well, Popeye in Technicolor. Stop Motion Marvels 2 had some wonderful material cleaned up this week. I’m hoping the Stop Motion Marvels Vol. 1 Blu-ray set has a scan session in the coming few weeks to accompany the films that just were scanned- it depends on a large group of films arriving from one collector. It would all be overwhelming if it wasn’t all coming out so well.

Last week, Google put up some wonderful little ‘Easter eggs’ on their search pages to celebrate the 80th Anniversary of the classic 1939 MGM film. The Metro (in the UK) did a nice article on the various features, so visit here first unless you’d like to be completely surprised!

It got me thinking about Ted Eshbaugh’s Wizard of Oz short, and the interesting history behind its creation.

Ted Eshbaugh’s “The Wizard of Oz”

Finding a good color print of this little film was at the very top of my ‘Holy Grail’ list for many years, followed closely by Eshbaugh’s The Snowman (1932) and Goofy Goat (1931). Eshbaugh is perhaps the most unusual of the independent producers; from viewing his independent output of films made at his studio as well as Van Beuren, you get a pretty good impression of the unique ideas and directorial touches that are present in his films. Perhaps the reason I was most excited about producing a Rainbow Parade set was the chance to get the best possible versions available of these Ted Eshbaugh directed shorts. Eshbaugh made three independent shorts (that we know of) between 1929 and 1933, then directed three shorts at Van Beuren for the ‘Rainbow Parade’ series in New York, Pastrytown Wedding (1934), The Sunshine Makers (1935) and Japanese Lanterns (1935). Seeing these three now almost finished and looking beautiful on their own made that whole project worth while. Between the Technicolor Dreams set and this new Rainbow Parade set, all except one will be available in 35mm prints. Maybe some day sooner than later Goofy Goat can be added to that list. Is it sitting in someone’s basement, recently rescued from a vault In New Jersey, or does it just not exist in 35mm? If a color print is found it’s a wonderful day for animation history.

Eshbaugh’s sincere attempts to advance color in animated cartoons is both a barely documented and important chapter in the history of animated films. His Goofy Goat (1931) has been listed as the first color/sound cartoon by some sources. Of course, it isn’t, but is one of the first. It’s preceded by both Iwerk’s Fiddlesticks (1930) released in Multicolor in the UK as well as Cy Young’s Mendelssohon’s Spring Song (1931) in Brewsterolor. Two other Flip the Frog cartoons, Little Orphan Willie (1930) and Puddle Pranks (1931), were probably also released in color in the UK.

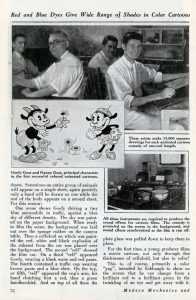

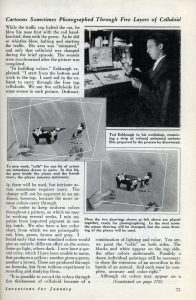

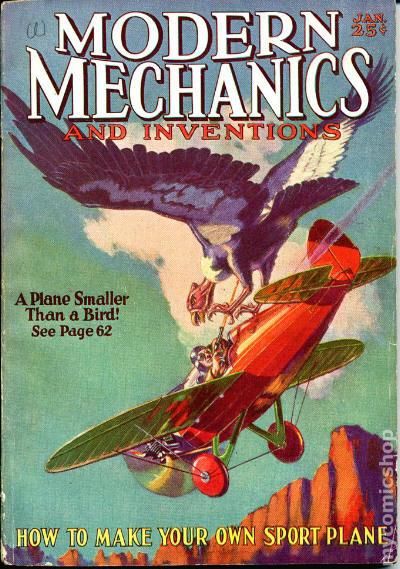

This wonderful article (from Modern Mechanics and Inventions January of 1932) presents a great idea of Eshbaugh’s personal involvement in the technical details of making the films. No color process is listed in this article, however, Technicolor’s records show that Eshbaugh was working *at Technicolor* in some capacity when this article was written. My guess is that the studio had nearly completed The Snowman (1932) by the time this article appeared. (Click each image to enlarge)

The cover of this issue

Technicolor’s records show a co-production deal with Eshbaugh, Rank Labs UK and J.R. Booth in late 1931 to produce the Wizard of Oz short. Booth owned Film Laboratories of Canada, the exclusive lab in Canada for the Technicolor process. It seems likely that Technicolor’s direct involvement with its production (and with Eshbaugh’s production company of the same address according to Technicolor’s records) was to refine the specifics of filming and printing a cartoon, producing a showpiece to interest other producers in the Technicolor process. It was a perfect showcase in a way since the film was to start in black and white and turn into full color once Dorothy arrived in Oz.

Disney’s contact with Technicolor, by popular telling, was initiated by one of Technicolor’s co-founders, Herbert Kalmus. What happened to the production of Eshbaugh’s The Wizard of Oz isn’t entirely clear, but it’s more likely that production on the film halted for a period of time around April 1932, close to the time that Disney signed the contract for exclusive use of the Technicolor process (through late 1935, originally longer). One has to wonder if some of the Wizard of Oz footage was viewed by Disney.

Eshbaugh formed a new company thereafter, and in October of 1932 an article announces the Wizard of Oz cartoon is in development at Eshbaugh’s Musicolor Fantasies Company on North Highland Ave.

In April of 1933, in a syndicated column by Hollywood writer Harrison Carroll, it is noted that Eshbaugh had finished the first Wizard of Oz cartoon. It’s interesting to note that whatever arrangement Eshbaugh had for the release of the film seems to have been scuttled by Technicolor sometime after this point. A Film Daily article from June 1933 notes that the film was brought to New York’s Du-Art film studios, and that Booth had an office there. I have to wonder if this the print that Eshbaugh owned, the same print acquired much later from Eshbaugh by the Library of Congress.

This is speculation, but from the facts of the situation, it seems as if Technicolor gave some impression that the film would be allowed release since they allowed it to proceed and the negative to be put together. At some point in 1933, did Technicolor, perhaps worried about their Disney contract, not allow its release when completed against a standing contract?

Eshbaugh and producer JR Booth sued Technicolor USA in 1934 for 14k, demanding the release of the Wizard of Oz negative. Rank Labs is named as a co-producer in the lawsuit. In June of the same year, Frank Baum sued Technicolor (not Eshbaugh or Booth) for copyright infringement in producing the Wizard of Oz cartoon. It appears that Technicolor acquired the rights from Baum’s cousin who claimed ownership. Perhaps Technicolor held onto the negative to prevent it from being printed by Booth’s film Laboratories of Canada (known also as Technicolor Canada), or Rank (who had rights to the Technicolor process in the UK). Both companies were independently owned rather than sister companies with Technicolor USA.

Here is Eshbaugh’s “The Wizard of Oz”. This 35mm Technicolor print is from Ted Eshbaugh’s personal holdings, donated to the Library of Congress, who generously allowed Thunderbean to scan it for the Technicolor Dreams and B/W Nightmares Blu-ray set. Youtuber Bilbo Barpkins’ posted the version of the film from the Thunderbean Blu-ray on January 10th this year (my birthday). Since he’s already done the work of uploading, here it is. Make sure to watch it in HD since it looks so nice!

(some research in this post is from the new book The Road to Oz: The Evolution, Creation, and Legacy of a Motion Picture by Jay Scarfone & William Stillman, Brown and Littlefield, 2019)

Steve Stanchfield is an animator, educator and film archivist. He runs Thunderbean Animation, an animation studio in Ann Arbor, Michigan and has compiled over a dozen archival animation DVD collections devoted to such subjects at Private Snafu, The Little King and the infamous Cubby Bear. Steve is also a professor at the College for Creative Studies in Detroit.

Steve Stanchfield is an animator, educator and film archivist. He runs Thunderbean Animation, an animation studio in Ann Arbor, Michigan and has compiled over a dozen archival animation DVD collections devoted to such subjects at Private Snafu, The Little King and the infamous Cubby Bear. Steve is also a professor at the College for Creative Studies in Detroit.

Steve:

I am ashamed to admit it, but I like this WIZARD OF OZ even better than the Judy Garland film.

I am a sucker for early Technicolor whether it be animated or live action. I have the restored KING OF JAZZ which looks amazing and features one of the very few color appearances of Oswald The Lucky Rabbit. And I love pretty much all the color cartoons on the TECHNICOLOR DREAMS AND BLACK AND WHITE NIGHTMARES.

I imagine the POPEYE IN TECHNICOLOR will feature the three double length featurettes as well as other public domain color Popeye cartoon that turn up on so many

pd collections. Feel free to reply,

-Chris

I bought Thunderbean’s Technicolor Dreams collection specifically for this film — and also, partly, for the original Brewster Color version of “Mendelssohn’s Spring Song”. (It’s Brewster-rific!)

What a magnificent cartoon this is, and in such excellent condition. The colours are so much more vivid and vibrant than in any of the early Disney Silly Symphonies. Some of the scenes — the butterfly, the peacocks, the Emerald City parade — are absolutely breathtaking. Unfortunately it’s marred by an anticlimactic ending, thanks to Eshbaugh’s poor sense of storytelling; it would have made more sense to have the hen produce a series of beautifully decorated Easter eggs, each bigger than the last, to take full advantage of the Technicolor process. But it’s still a wonderful film. As with the MGM feature, I can watch it over and over again and simply marvel at it.

If I may digress slightly: Does anybody remember an extremely low-budget Wizard of Oz cartoon series made for television in the early 1960s? “Three sad souls, oh me! Oh my! / No brain! No heart! He’s much too shy!” The scarecrow was called Socrates, the tin man Rusty, and the lion Dandy; and I have the impression that the music was scored for woodwind quintet. Has any effort been made to preserve this series, and if not, would it even be worth the bother?

Paul, someone may have answered this but they were made by Crawley Films in Ottawa with the voice tracks cut in Toronto by a bunch of old radio actors. They were done for Videocraft, which became Rankin-Bass.

I used to see those every week on WBZ’s “Boomtown” in Boston, MA in the early 60s.

You’re thinking of / remembering the Rankin/Bass “Tales of the Wizard of Oz”.

They also made a 1964 hour-long TV animated special, “Return to Oz” (which is available on DVD).

Personally, I think a color print of “Goofy Goat (Antics)” does exist, just mislabeled and archived unknowingly at a museum or hidden away at the library of congress. It’s stated that he donated a color print to a history museum (I have written down somewhere, don’t recall which one) along with his desk. From reading trade ads while researching Eshbaugh, I always got the impression that Goofy was a film he was extremely proud of as it was always mentioned and credited as the ‘first’ color sound cartoon. Seeing how he or his family donated a lot of his films, such as “The Snowman”, “The Wizard of Oz”, “The Sunshine Makers”, etc. to the library of Congress, I find it hard to believe that Eshbaugh would have junked any color prints or negatives he had of Goofy Goat.

Hi Jonathan,

That “History Museum” to which Ted Eshbaugh donated the print of “Goofy Goat”, may have been the Los Angeles Museum of Natural History in Exposition Park. I once saw a beautiful cardboard display in a hallway at the L.A. Museum, which had the actual color title card from “Goofy Goat” and several cels from the cartoon, and a drawing of what the camera stand looked like that shot the cartoon. So that makes me very curious, did Eshbaugh donate a print of the cartoon to the L.A. Museum along with the artwork that they hold on “Goofy Goat”? Does anyone reading this have any special pull with the L.A. Museum of Natural History and could find out what happened to the Eshbaugh materials?

oh, my dear GOD!! I had seen this film a handful of times….and with never much fanfare. This renovation is STUNNING! I thank thee!!!

Thanks to You Tube videos, I’d begun to like this “WIZARD OF OZ” series all over again, and I found that it did sound familiar to me. I believe one of the voices in the series was Jonathan Winters. It was posted about already on Cartoon Research; do a quick search, and I think you’ll come up with the piece and, perhaps, enough historical information on it. It would be worth owning on physical media as this is something that no one would otherwise think to preserve for regular streaming. I’m still waiting for the definitive version of the 1939 film. Each edition seemed to have some fancy gimmick, and I did unfortunately buy the set where there is a 3-D(?) version of it and the soundtrack has been redubbed into stereo! Forgive me if the sound was originally meant to be that way, although I very much doubt it since Disney tried his hand at stereo in 1942 with “FANTASIA” and the separation was nowhere near as intricate as it is in the final Warner Home Video version of “THE WIZARD OF OZ” in this box!

Again, I digress, but the television series of “OZ” cartoons should be preserved, and I believe the article that is somewhere on Cartoon Research also wished for that same thing. Keep tooned, as they say…

To Steve Stanchfield: Ooh, as usual, I am hopeful for the outcome of the disks that you’ve said are so close to completion, including the kick-starter disks. FLIP THE FROG and RAINBOW PARADE are at the top of my list, as is anticipation growing for the PUPPETOONS disk. It certainly must be exciting to finally see these cartoons suddenly given new and improved life with each digital frame and colors as vibrant as we can get them from sources over 50 years old! Preserving certainly must be such a challenge, and we are unfortunately finding out that digital sources also decay and, unlike film, cannot be revived once that decay kicks in! This is why restorations are necessary and I can only echo so many other fans in saying that the large studios should spend the bucks to make sure that decay doesn’t happen as fast as the efforts to preserve!

When I became interested in film sound in high school (1968), I came across a reference in the Cameron books to the Ted Eshbaugh WIZARD OF OZ planned as a series in Technicolor. And they way this cartoon ends, it seems to suggest that further adventures could follow. But for many of the reasons noted here, that never came to be. Most of the accounts conclude that Disney’s “exclusivity” to the Three Color Process had a great deal to do with limiting mass distribution of the Eshbaugh production. Other accounts suggest that there was a “rights” issue to was also a barrier, with Samuel Goldwyn having the rights at one time until they were purchased by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1938. In the process, MGM had an archival print, and for decades a black and white 16mm dupe version has circulated among collector’s circles.

In the 1990s, a color version with weak color turned up on a Public Domain VHS tape released. This is certainly nice to see in its true display. And what it represents appears to be a production designed to display the Technicolor process primarily. It is also interesting that it suggests the same concept of a colorless Kansas and a full Technicolor OZ, which the MGM film followed. Whether suggested by this cartoon, or by realization based on the description in the book, this is worth considering.

From a production standpoint, it is a curiosity on another level. First, it’s odd and disappointing that The Cowardly Lion is excluded. Second, it seems that the cartoon is focused on “going through the motions” and pays no attention to character development or realization of “personality” animation, an area that Disney focused on.

While the use of color is beautiful, the cartoon seems under developed in content. In spite of its deficiencies, the Eshbagh WIZARD OF OZ remains an important part of animation and Technicolor history worthy of recognition and rediscovery.

Hi there! I’m doing some undergrad research on this film for a film history paper and was wondering if you remember what book you read this in? Is Cameron the author? (sorry i’m an animation / film history newbie)

It’s interesting that the Kansas sequence in the cartoon is in black-and-white, just like the 1939 live-action film. I wonder if anyone at MGM watched the cartoon as a reference?

As far as preserving digital media is concerned, it should be noted that major studio archives not only make copies of digital masters on hard drives, but also on digital tape! There is that worry that the mechanical part of a hard drive could fail at any time, so a tape is an alternate source. I’m betting that as SSD capacities increase and the costs go down, we’ll be seeing these used as an archival source, too.

The rights to the Wizard of Oz (the first book, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, that is) were kind of interesting. They were held by both author and illustrator jointly, allowing both of them to create more works featuring the characters. Author L. Frank Baum would go on to write his legendary sequels, while illustrator W.W. Denslow would write short stories about the Scarecrow and Tin Man for newspapers and use the characters in illustrations in other books he produced. (Denslow’s death in 1915 didn’t seem to leave his rights to anyone who exploited them at all.)

The two had gone their separate ways shortly after the book’s publication, and they even had a nasty dispute over the royalties from the big stage show adaptation in 1902.

Later, Baum put together a lavish multimedia show featuring slides and short film clips and live actors to promote his books titled the Fairylogue and Radio-Plays. The show was a massive financial failure and drove Baum to bankruptcy, causing him to sign over the royalties and rights to many of his earlier books—including the Wonderful Wizard of Oz—to his creditors, letting the sales of those books eventually pay them back. These rights were reclaimed by his widow Maud Gage Baum after his death in 1919.

Baum’s oldest son, Frank Joslyn Baum (aka “Frank Jr.” or “Frank Baum” and had served in World War I, achieving the rank of lieutenant colonel) had been made executor of the Oz rights and had a hand in the Wizard of Oz silent film by Larry Semon in 1925. It seems he was involved with the Eshbaugh cartoon as it says he was responsible for the story in the cartoon, crediting him as “Col. Frank Baum.” In the book “100 Years of Oz,” a sample of Frank Jr.’s stationery is seen from the collection of Willard Carroll, and it features the Eshbaugh characters. (This book has been reprinted as “The Wonderful World of Oz: An Illustrated History of the American Classic.”) Frank Jr. also attempted to launch a very unsuccessful Oz toy line.

Frank Jr. suing over the cartoon is a bit surprising, but not very much considering that he attempted to capitalize on Oz exclusively. He published an Oz short story to try to trademark “Oz” himself, and then sent a cease and desist letter to Reilly & Lee, the publisher of the L. Frank Baum Oz books (except for Wizard, their flagship title was in fact the first Oz sequel) and its sequels by Ruth Plumly Thompson. This led to his mother Maud suing against him to claim the trademark for herself as she was receiving royalty payments from Reilly & Lee for new Oz books.

Frank attempted to begin his own series of Oz stories with Whitman Publishing, but the unlicensed first book was sued out of print by Reilly & Lee.

In 1933, Samuel Goldwyn set out to buy the rights for The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, but Frank Jr. had to prove he was able to do so in court, which meant the rights were signed over in late 1934. Perhaps Frank Jr.’s lawsuit was trying to use any reason he could to prevent the cartoon from being released to ensure they’d get a good payout from Goldwyn.

Goldwyn’s fee would, in fact, be the last big license deal the rights would get for the Baum family before the copyright expired in 1956 as Goldwyn—after years of trying to figure out how to make an Oz film of his own—was the one who sold the rights to MGM shortly after the success of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Frank Jr. was supportive in the formation of the International Wizard of Oz Club before his death in 1958 and worked with Russell P. MacFall on the creation of “To Please A Child,” the first biography of L. Frank Baum. Further research and biographies surpassed this book in many ways as it was discovered it had a large amount of false information.

I’m not trying to argue with any of the information presented by Steve here, but Frank Jr. was certainly quite the character.

Anyone ever figure out who “Hutch” was?

I think his last name was “Hutchinson”, “Hutch” Hutchinson. I don’t remember his other credits.

The animator was named Andrew Hutchinson. His career dates to the silent era.

I have a copy of this cartoon in both my copies of the 1939 feature film (both VHS and DVD); enjoyable.

The print that was posted here of the 1933 Oz cartoon far outdoes the version released on DVD by Warner Home Video, which I still have, by the way. The print is sharp, the colors vibrant. Certainly the best it has ever looked,

Don’t feel bad about the problem with archiving.

At Disney we saved data (not the image) on different tape formats but the only way to confirm if all files are saved correctly is to download the tape onto a drive and compare the total byte count.

All drive formats have problems. At other studios, magneto optical drives had the biggest problems and I trust they’re no longer in use.

At Paramount/Viacom, productions that I worked on and saved to D1 tape lasted only 10 years. They instituted a program to constantly re-save digital formats but I’m not convinced it’s working.

Whenever I get called in for a reconstruction I ask to see the check print made from the supposed 35mm YCM they make off a film recorder. And they always refuse which does not instill confidence.

To the readers here, the best way to archive productions remains 35mm successive exposure film. Do not let anyone talk you out of that.

I LOVE having this “Technicolour Dreams / B&W Nightmares” DVD+Blu-ray set, especially with the inclusion of this restored, clean and vibrant presentation of Oz pre-MGM!! And I also love the “Enchanted Square” (despite a tiny bit missing).

I wish the NEW print version of “Wizard” would be included by WB on their future releases of the 1939 film that featured other/earlier films versions of Oz, as it would be a brilliant upgrade and improvement from their previous home video releases.

As always I am eagerly looking forward to and awaiting the completion and release of your presentation for Lou Bunin’s “Alice in Wonderland” set – I cannot wait but I am being patient and know you will not disappoint, but surprise us delightfully!!

Is it possible that this edition of Eshbaugh’s “Wizard of Oz” cartoon originated with a sound-on-disc original? The audio is very clear, with pretty good bass response, but it also seems to have some surface noise — all of which suggests the use of a phonograph record, instead of an optical sound track.