A series based on Revolutionary times? This novel concept, shortly predating the inception of The Flintstones, found its origins not in television, but in theatrical cartoons, eventually morphing into a syndicated television series, yet retaining its roots in continued theatrical releases extending beyond its television run.

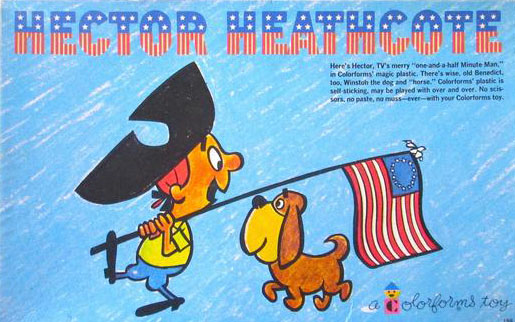

The most “revolutionary” of all theatrical characters was Terrytoons’ Hector Heathcote. Created by Dave Tendlar, newly relocated to Terry from practically across the street as Paramount’s cartoon budget shriveled, Hector, a puny, unassuming weakling of a patriot in minuteman’s hat, would become the studio’s go-to man not only for recurring jaunts into the Revolutionary War days, but for ventures to almost any other historical period of the past, nearly always retaining his minuteman outfit no matter what the historical era. The underlying premise of the series was to tell the tale of the little guy no one knows who somehow (usually by utter accident or random happenstance) changes the course of history despite his own obvious shortcomings – the “unsing hero”. The premise had lasting potential and ample opportunities to supply humor, and resulted in enough shorts to fuel a short-lived weekly series under the character’s name.

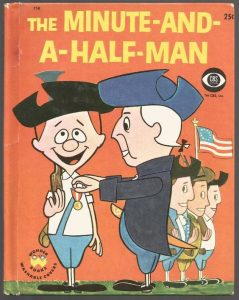

Appropriately, Hector debuted with The Minute and a Half Man (Terrytoons/Fox, 7/4/59 – Dave Tendlar, dir.). Heathcote desperately wants to be counted among the town’s voluntary militia, dedicated to the cause of assembling on a minute’s notice. Except Hector just can’t seem to clock in under the mark of the militia leader’s stopwatch. Something always goes wrong. An attempted exit from the house trips him up on the bottom half of a swinging Dutch door. A jump into his clothes from bed results in his suspenders caught on the bedpost, slingshotting him back into the house and collapsing his bed canopy atop him. He digs a tunnel for a direct line to the town square, but is intercepted by a cannonball knocked into the other end of the tunnel by a passing patriot. Sleeping atop the town square flagpole, Heathcote gets his musket barrel stuck on the flagpole end as he tries to get down, bending the pole and catapulting him into a chimney on the opposite end of town. A rocket fastened to his back fizzles, then ignites while he has its nose pointed downward, blasting him into the ground and up the inside of the flagpole. Finally, Heathcote builds a humongous inclined ramp from the top of his house to the parade grounds, and a springboard mechanism inside his home to launch him into a wheeled chair on the ramp at the cutting of a rope. The redcoats invade by sea, with a stuffy British officer in the lead looking through a spyglass. The militia bugle sounds, and Heathcote is off. Only waiting at the bottom of the ramp, directly in his path, is the rear end of a mule. Collision occurs, with the mule arriving in the wheeled chair at the parade grounds – while Heathcote flies through the air and into the mouth of a cannon. The cannon rolls down a hill and into the ammunition dump, setting off a hail of shot and shell. The British officer’s view is blocked, as a cannonball hits squarely upon the lens of the spyglass. Without a word of ceremony, the British march hastily in reverse, board their ship, and sail back to Merry Olde England. A battered Hector is carried on the shoulder of his fellow patriots as a hero. In the present day, a narrator shows us the famous park statue of the minuteman, but mentions that if you look hard enough – behind a bush – you can also find a smaller statue of Hector – who took a minute and a half, but came through.

Appropriately, Hector debuted with The Minute and a Half Man (Terrytoons/Fox, 7/4/59 – Dave Tendlar, dir.). Heathcote desperately wants to be counted among the town’s voluntary militia, dedicated to the cause of assembling on a minute’s notice. Except Hector just can’t seem to clock in under the mark of the militia leader’s stopwatch. Something always goes wrong. An attempted exit from the house trips him up on the bottom half of a swinging Dutch door. A jump into his clothes from bed results in his suspenders caught on the bedpost, slingshotting him back into the house and collapsing his bed canopy atop him. He digs a tunnel for a direct line to the town square, but is intercepted by a cannonball knocked into the other end of the tunnel by a passing patriot. Sleeping atop the town square flagpole, Heathcote gets his musket barrel stuck on the flagpole end as he tries to get down, bending the pole and catapulting him into a chimney on the opposite end of town. A rocket fastened to his back fizzles, then ignites while he has its nose pointed downward, blasting him into the ground and up the inside of the flagpole. Finally, Heathcote builds a humongous inclined ramp from the top of his house to the parade grounds, and a springboard mechanism inside his home to launch him into a wheeled chair on the ramp at the cutting of a rope. The redcoats invade by sea, with a stuffy British officer in the lead looking through a spyglass. The militia bugle sounds, and Heathcote is off. Only waiting at the bottom of the ramp, directly in his path, is the rear end of a mule. Collision occurs, with the mule arriving in the wheeled chair at the parade grounds – while Heathcote flies through the air and into the mouth of a cannon. The cannon rolls down a hill and into the ammunition dump, setting off a hail of shot and shell. The British officer’s view is blocked, as a cannonball hits squarely upon the lens of the spyglass. Without a word of ceremony, the British march hastily in reverse, board their ship, and sail back to Merry Olde England. A battered Hector is carried on the shoulder of his fellow patriots as a hero. In the present day, a narrator shows us the famous park statue of the minuteman, but mentions that if you look hard enough – behind a bush – you can also find a smaller statue of Hector – who took a minute and a half, but came through.

Here’s the cartoon – with subtitles:

The Famous Ride (Terrytoons/Fox, 4/1/60 – Connie Rasinski/Dave Tendlarm dir.) is somewhat less impressive than its predecessor. Stable proprietor Heathcote receives the assignment to ready Paul Revere’s horse for immediate need in a ride that evening. As Paul waits on the riverbank for the famous signal, Heathcote engages in a battle of half-wits with the horse, who keeps backing up every time Heathcote mounts a stepladder to take his reins. The horse puts Heathcote in a spiral when he gets caught on a nail, and shines his hoofs against the whirling Hector. Heathcote places the horse in the latest in horse washes, resembling a primitive car wash stall – until the horse changes places with him under the suds and soaks him with water, turning his water-filled hat inside out, Attempts to tie the horse down only result in the horse pulling out the stake securing one rope and conking Hector on the head with it. A primitive hydraulic lift allows the horse’s hooves to be polished, until the horse pulls the down lever, causing Heathcote’s ladder to spring him out the window. Heathcote winds up hanging from a flagpole, his face turning an embarrassed red, while his white shirt and blue pants cause a passing patriot to salute him like a flag. Finally Hector succeeds in binding the horse up like a bundle suspended in mid-air from a rope and pulley, and greases his hooves with an oil can, then combs out his tail. In comes Revere, having received the signal, and gallops to spread the word – not realizing Hector is being dragged behind, his comb caught in the horse’s tail. Hector is bounced around, and winds up hanging from the horse’s neck for the duration of the ride.

Drum Roll (4/4/61 – Dave Tendlar, dir.), recounts the unsung tale of the military exploits of the 33 (and a third) Company. Fresh from a resounding victory against the British stronghold of – Crumpet Rock (?), the unit is shelled from a British-held fort ahead. Their commander orders a small squad to infiltrate enemy lines to determine how many troops and ammo the British have. Heathcote, the company drummer boy, immediately volunteers, but is consider too puny and ineffectual for the mission. “Take your drum and BEAT IT”, shouts his sergeant. While the scouts creep softly forward, Heathcote rejoins the ranks from the rear, and starts beating out a march riff on his snare drum – revealing their position and drawing another round of British fire. The sergeant breaks his drumsticks in two, but resilient Heathcote whittles another pair out of some twigs. Trying them out, he beats out a rhythm on the Sergeant’s head as he again creeps through the brush. Running for cover, Heathcote stumbles, and winds up log-rolling atop his drum, right into the commander’s headquarters. Seeing the drum and its equally-sized owner, the commander gets a stroke of military genius – to place Heathcote inside the drum, then roll it into the enemy fort. Hector is launched by a well-placed kick in the manner of a football, and propelled into the fort door. One mishap after another results from the drum’s random rolling and ricochets, causing the British officer to be knocked into a cannon, blasted skyward to fall into the drum head on one side of the drum, while Hector’s feet protrude out the other, loosen a flagpole which the officer finds himself holding like a knight’s lance, spear three cannons through their barrels, and roll the whole mess into the ammunition dump, exploding the fort. Hector (or rather his drum) receives a series of medals, while Hector happily takes a closing solo with his sticks, with the announcer stating, “Play it, man.”

A Bell for Philadelphia (7/1/63 – Bob Kuwahara, dir.) is currently unavailable for Internet viewing – but its audio was preserved on the RCA Camden “Hector Heathcote Show” soundtrack LP. Moving man Hector is given a preliminary chance to move a valuable antique desk to the State House, with the possibility of the prestigious job of moving the Liberty Bell if he does the work well. Of course, puny Hector lets the desk slip, crushing his wagon and the desk, too. But his rival, the evil Benedict, is not much better. Given the job of moving a Liberty Bell cast for the colonies in England, Benedict shows off for the crowd, balancing the bell on one finger. The bell falls out of control, and is broken into itty bitty pieces, a total loss. A new bell is cast in Philadelphia, and Hector is called back for the less risky job of merely moving the bell from foundry to State House. Benedict, however, lures Hector’s horse with a carrot just as Hector is trying to load the bell onto his wagon, resulting in the Bell falling on Hector and our dazed would-be patriot falling with the bell into the river. Heading for a waterfall, Hector’s fate is sealed by Benedict sawing off a branch he attempts to cling to. But somehow, Hector survives the drop, and stumbles out onto the riverbank, still inside the bell. Benedict tosses a log under his feet, and Hector logrolls his way down a steep hill and into a wall. The bell goes sailing over the wall – and flies into the State House bell tower – delivery accomplished. Heathcote is the unlikely unsung hero once again.

A Bell for Philadelphia (7/1/63 – Bob Kuwahara, dir.) is currently unavailable for Internet viewing – but its audio was preserved on the RCA Camden “Hector Heathcote Show” soundtrack LP. Moving man Hector is given a preliminary chance to move a valuable antique desk to the State House, with the possibility of the prestigious job of moving the Liberty Bell if he does the work well. Of course, puny Hector lets the desk slip, crushing his wagon and the desk, too. But his rival, the evil Benedict, is not much better. Given the job of moving a Liberty Bell cast for the colonies in England, Benedict shows off for the crowd, balancing the bell on one finger. The bell falls out of control, and is broken into itty bitty pieces, a total loss. A new bell is cast in Philadelphia, and Hector is called back for the less risky job of merely moving the bell from foundry to State House. Benedict, however, lures Hector’s horse with a carrot just as Hector is trying to load the bell onto his wagon, resulting in the Bell falling on Hector and our dazed would-be patriot falling with the bell into the river. Heading for a waterfall, Hector’s fate is sealed by Benedict sawing off a branch he attempts to cling to. But somehow, Hector survives the drop, and stumbles out onto the riverbank, still inside the bell. Benedict tosses a log under his feet, and Hector logrolls his way down a steep hill and into a wall. The bell goes sailing over the wall – and flies into the State House bell tower – delivery accomplished. Heathcote is the unlikely unsung hero once again.

Search for a Symbol (9/1/63 – director credits unavailable) casts Heathcote as the proprietor of a colonial pet shop, in the same town where a debate rages in the Capitol building as to what animal should serve as the symbol for our country’s patriotic spirit. Practically every type of animal is suggested – down to a tap-dancing horse, and a warring dog and cat. Meanwhile, Hector notices his shop is short on birds, and goes out in the woods to hunt up some new stock. Accompanied by his dog Winston (a sidekick character added in the later years of the series, whose droll British-accented comments were always underplayed in deadpan manner), Heatcote spots an eagle in a tree, and thinks he’ll draw a handsome price. A war of wits and wings ensues. Highlights include Hector building a towering, teetering pile of rocks to reach the bird in a high mountain perch, with Winston commenting in prophetic words that Heathcote is bound to “go down in history”. Another trap has Heathcote rig a false nest over a barrel, then hammer down a lid on the barrel as the bird falls into it. Unfortunately, Heathcote overlooks two knotholes – big enough for the bird’s wings to protrude through, and lift Heathcote and the barrel airborne. Ultimately, they crash into a flagpole near the state house, with the bird settling majestically atop the pole. The convention delegates see, and unanimously approve this inspiring sight for their new symbol, while Hector, obscured from view by the pole, goes without historical notice again. Winston provides the final comment: “You might find this hard to believe – and you’re right.”

Valley Forge Hero (10/1/63 – director credits unavailable) is perhaps the most routine of the Revolutionary-themed Hectors currently available for viewing. One original touch, however, is having the American flag frozen stiff in icicles over the encampment. Camp Cook Hector is ordered by Captain Benedict to find food, and reminded by him that an Army marches on its stomach. Hector is well prepared for this, having an old shoe strapped to his tummy. An Army manual suggests ice fishing. As Hector saws at the ice, Winston comments, “At least he can’t saw himself off a tree limb – but I’m sure he’ll do the next best thing.” He does, cutting the circle of ice around Benedict, dumping him into the icy water. A frustrating attempt by Benedict to build a fire by striking two stones together only produces a blaze when Hector adds a horn of gunpowder to the kindling – of courrse, its side-effects on Benedict are obvious. The finale gets Hector into the old rolling snowball gag, bowling over everything in his path for miles, and crashing into a structure – the supply depo, to which he’s miraculously cleared a road. Hector receives a decoration – the good conduct icicle.

At least two other Heathcote theatricals were Revolutionary-themed: Crossing the Delaware (6/3/61 – Art Bartsch, dir.), and Tea Party (5/1/63 – Dave Tendlar, dir.). Regrettably, neither are available for viewing on the Internet. I believe I saw “Delaware”, which had to do with Hector (and rival Benedict?) running boat rental businesses – there may have been a closing gag with Hector swimming along under Washington’s boat to keep a leak plugged. I’m not sure if I ever saw “Tea Party”. Anyone with information on these titles is welcome to contribute.

Popeye Revere (King Features, Popeye, 1960 – Jack Kinney, dir.) is actually a mistitling, as the subject character is not named Popeye, but is Popeye’s great great granddaddy Poopdeck. (Considering Popeye’s father is also named Poopdeck, the name must have been handed down several generations.) Popeye relates to Swee’pea how the ride of Paul (Poopdeck) Revere really happened. The tale is actually set out pretty straightforwardly, with few gag embellishments. Casting goes to Wimpy for the signaler in the Old North Church (without even a chance to down a hamburger). Bluto (aka Brutus) is cast as a Tory (at least colorful in a flashy red outfit) who spots Poopdeck out with his horse late at night, and deduces the tower lights to be a signal. He attempts to interfere by dousing Poopdeck in a molasses barrel. Poopdeck turns to a tin full of spinach snuff, consuming a pinch of same and acquiring his superpower with a sneeze. He really doesn’t use the power much, simply shooting up out of the barrel into the air, then landing on Bluto to place him in the same sticky mess. Now comes the ride, which is portrayed almost dead straight. (Swee’pea provides a comment on Popeye’s poetry by way of a sign earlier in the picture, which is one of the only reasonable laughs in the episode – the sign states, “Real Corn”, with an ear of same as an illustration.) When Popeye is through, Swee’pea asks how Poopdeck managed to ride that long through the night, and Popeye states he was saved by the molasses, which stock him to the saddle. Swee’pea tells the audience this is a really sticky story, but Popeye closes with “Yeah, but you’re stuck with it.”

Popeye’s Tea Party (King Features, Popeye, approx. 1960 – Jack Kinney, dir.) tries for a bit more action. But given the threadbare budgets of Kinney’s later productions for the series, the animation is roughshod and falls short of expectations. First, without any need for same (as the episode could easily have stood alone as a true period piece by just flashing a date over an establishing shot), Kinney uses one of his standard “cheats” by repeating over a full minute of stock animation of Professor Whattaschnozzle putting Popeye in a time machine. (You’ve seen this same animation before if you dared to watch Invisible Popeye in my previous series, The Invisible Article.) Once Popeye does land in Boston, he witnesses tax collector Brutus posting a Proclamation as to the new tea tax – same as before plus 50% for the tax collector. Restauranteur Wimpy complains this will ruin his business (his posted menu including such bill of fare as tea burgers, tea bone burgers, tea spinach, and tea 2¢ plain). Popeye speaks out (in a glaring animation error where the cels shift so that the cutoff line where his legs are supposed to be out of camera range rises into the frame area, causing him to stand legless in the air – an error not seen since the 1940’s in Paramount’s Robin Hood-winked, when a background element which was supposed to eclipse Bluto’s legs was not placed on he camera mount). “No taxation without resentment”, Popeye declares. The townsfolk, including Olive and Swee’pea, conspire to throw the tea overboard, while Brutus eaves-drops and plots to sabotage the plan.

At night, Popeye, Olive, Swee’pea and Wimpy creep on board the tea frigate, wearing Indian feathers and with bows and arrows, periodically shushing each other to keep quiet. An extra shush is heard, as Brutus chimes in behind a stack of tea sacks. Popeye starts heaving tea sacks away over his shoulder. “Tea off! Tea for sea!” “Tea for two” shouts Brutus, catching the sacks short of the railing, and heaving them all at once back onto Popeye. “One lump or two”, retorts Brutus. But behind him, Swee’pea draws a bead with a bow and arrow on Brutus’s large rear – “Target for tonight.” Brutus does not take kindly to the shot, and tosses Swee’pea overboard. From the stern of the ship, Swee’pea dangles from a nail caught in his swaddling clothes, saying “A nail in time saved mine.” Popeye demands to know where Swee’pea is, and is shown by also being tossed over the side. “Lend me your bow and arrow”, Popeye calls to Swee’pea. With deft shots, Popeye shoots six arrows into the side of the ship to provide a pre-fab staircase. Brutus waits on deck with a large club. Wimpy lapses into one of his rare heroic moments, pulling an arrow from his quiver in an attempt to save Popeye – but finds that the arrow tip has speared a hamburger he also packed along. “I can’t waste this shot”, he concludes, and begins eating. Meanwhile, Brutus bats Popeye across the deck and into the mouth of a cannon. Coincidentally, Wimpy chooses this moment to accompany his meal with some fresh-brewed spinach tea, and lights the cannon’s fuse to provide the brewing flame under his pot. As Brutus drags Olive up the ship’s ratlines, saying “Come up and see my rigging”, Popeye asks Wimpy for some of that spinach tea. An interesting bit of role reversal occurs here, as Wimpy insists, “Two shillings for tea.” Popeye, with his arms caught inside the cannon barrel, uses Wimpy’s old line: “I’ll gladly pay ya’s Tuesday for tea today!’ Wimpy extends credit, pouring the tea into Popeye’s pipe to the brim. The cannon fires, and Popeye shoots into the skies, landing a headfirst blow into Brutus’s gut atop the mainmast. Olive balances precariously on a spar and is saved by Popeye. As Brutus rises to retaliate, Swee’pea, who has finally gotten free of the nail and climbed back aborad ship, aims another perfect arrow shot at Brutus’s rear end. Brutus shouts in pain, and falls overboard into the drink. The final shot shows Brutus locked in the stocks, and cutting a deal. “I don’t tax you, and you don’t tax me. Okay?” “Okay”, replies Popeye, but with a proviso – he plasters Brutus’s tax stamps all over his Brutus’s face, stating, “But this is for amusement tax, and that’s tax free!”

At night, Popeye, Olive, Swee’pea and Wimpy creep on board the tea frigate, wearing Indian feathers and with bows and arrows, periodically shushing each other to keep quiet. An extra shush is heard, as Brutus chimes in behind a stack of tea sacks. Popeye starts heaving tea sacks away over his shoulder. “Tea off! Tea for sea!” “Tea for two” shouts Brutus, catching the sacks short of the railing, and heaving them all at once back onto Popeye. “One lump or two”, retorts Brutus. But behind him, Swee’pea draws a bead with a bow and arrow on Brutus’s large rear – “Target for tonight.” Brutus does not take kindly to the shot, and tosses Swee’pea overboard. From the stern of the ship, Swee’pea dangles from a nail caught in his swaddling clothes, saying “A nail in time saved mine.” Popeye demands to know where Swee’pea is, and is shown by also being tossed over the side. “Lend me your bow and arrow”, Popeye calls to Swee’pea. With deft shots, Popeye shoots six arrows into the side of the ship to provide a pre-fab staircase. Brutus waits on deck with a large club. Wimpy lapses into one of his rare heroic moments, pulling an arrow from his quiver in an attempt to save Popeye – but finds that the arrow tip has speared a hamburger he also packed along. “I can’t waste this shot”, he concludes, and begins eating. Meanwhile, Brutus bats Popeye across the deck and into the mouth of a cannon. Coincidentally, Wimpy chooses this moment to accompany his meal with some fresh-brewed spinach tea, and lights the cannon’s fuse to provide the brewing flame under his pot. As Brutus drags Olive up the ship’s ratlines, saying “Come up and see my rigging”, Popeye asks Wimpy for some of that spinach tea. An interesting bit of role reversal occurs here, as Wimpy insists, “Two shillings for tea.” Popeye, with his arms caught inside the cannon barrel, uses Wimpy’s old line: “I’ll gladly pay ya’s Tuesday for tea today!’ Wimpy extends credit, pouring the tea into Popeye’s pipe to the brim. The cannon fires, and Popeye shoots into the skies, landing a headfirst blow into Brutus’s gut atop the mainmast. Olive balances precariously on a spar and is saved by Popeye. As Brutus rises to retaliate, Swee’pea, who has finally gotten free of the nail and climbed back aborad ship, aims another perfect arrow shot at Brutus’s rear end. Brutus shouts in pain, and falls overboard into the drink. The final shot shows Brutus locked in the stocks, and cutting a deal. “I don’t tax you, and you don’t tax me. Okay?” “Okay”, replies Popeye, but with a proviso – he plasters Brutus’s tax stamps all over his Brutus’s face, stating, “But this is for amusement tax, and that’s tax free!”

Surrender of Cornwallis, from the “Peabody’s Improbable History” segment of Rocky and His Friends (Jay Ward Productions) allows Mr. Peabody (dog genius) and his boy Sherman to visit the surrender that ended the revolutionary war, via Peabody’s patented WABAC machine. However, they find George Washington issuing orders readying his men for battle. Inquiring of one of the soldiers what happened to the surrender, they are informed that Cornwallis never showed up, and the Battle of Yorktown is ready to start all over again. Certain that something has gone amiss, Peabody takes Sherman to Cornwallis’s headquarters. There they find Cornwallis rummaging hopelessly through an old sea chest. He claims he can’t surrender – because he can’t find his ruddy sword to surrender with. The best he can locate is a cricket mallet, which he attempts to present to George. He returns a few moments later, with the bat busted over his head. “No dice?” Peabody and Sherman politely observe. Cornwallis decides he’ll “catch” a sword – and in a daring exhibition of deep sea fishing lands a swordfish. Unfortunately, it being a hot day and a long walk from the beach to George’s camp, the fish reeks by the time it is presented – and again gets whomped over Cornwallis’s head. Peabody asks if Cornwallis remembered to bring his sword on the trip. Cornwallis recounts his packing step by step – and remembers he left the sword on the dresser back in England. Never-say-die Peabody determines to set history right. Climbing into one of Cornwallis’s fastest ships, they conveniently catch a hurricane headed across the pond for a crossing in record time. At his home, Cornwallis discovers his mother using the sword as a skewer for a roast shish-kabob Promising to eat the roast on the return voyage, Cornwallis races with Peabody back aboard ship, where they catch the same hurricane now blowing in the other direction! Just before sunset, the surrender is made, and history preserved. Peabody’s trademark ending pun is so weak and off-point from the cartoon’s content in this episode that I will not even justify its presence by repeating it here – watch the cartoon for it, if you even care.

Mister Magoo’s Paul Revere (4/24/65, Abe Levitow, dir.), was the final episode of The Famous Adventures of Mister Magoo, an NBC primetime series attempting to spin off from the success of the seasonal Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol TV special with weekly tales of adventure told by Mr. Magoo in his Broadway acting profession established in the preceding special. The series actually did much less with the elements of Magoo’s persona than the previous special, and bore little resemblance in writing style to the cartoons of old, with Magoo only appearing as the bumbling, blustering character we love in a brief one and a half minute introduction to each episode in his dressing room. Here, he dons shoe boxes instead of shoes as part of his costume, attributing their length to the wardrobe department attempting tio remind him that the author of the work in question was a certain “Longfellow”. The telling of the title story, however, is played almost entirely for the dramatic, as was custom for the series when Magoo assumed a role. Animation is simple but effective, with some nice atmospheric background work, as was a specialty of Levitow’s productions. The tale encompasses multiple events, including both the Boston Tea Party and the midnight ride. General Gage is oddly portrayed as an indecisive and gullible type, while his lieutenant does most of the conniving. Magoo gets to play one scene comedically, using a jug of hard cider borrowed from a fellow patriot to learn news of the British’s means of attack. Pretending to be drunk, he stumbles over to a British soldier and offers him a friendly drink. The disgusted soldier states he’ll get all the rum he wants when he gets aboard ship – and thus spills the beans that the attack will be by sea. History is particularly rewritten, as Magoo himself hangs the lanterns in the Old North Church, then also rows across the river to take on the ride on the other side (rather an inefficient waste of time, when a simple signal to someone by lantern would have saved the time of the boat ride). The ride is presented in straightforward fashion, and ends with the shot heard round the world and an American flag dissolving into the heavens as the new day’s sunrise.

Mister Magoo’s Paul Revere (4/24/65, Abe Levitow, dir.), was the final episode of The Famous Adventures of Mister Magoo, an NBC primetime series attempting to spin off from the success of the seasonal Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol TV special with weekly tales of adventure told by Mr. Magoo in his Broadway acting profession established in the preceding special. The series actually did much less with the elements of Magoo’s persona than the previous special, and bore little resemblance in writing style to the cartoons of old, with Magoo only appearing as the bumbling, blustering character we love in a brief one and a half minute introduction to each episode in his dressing room. Here, he dons shoe boxes instead of shoes as part of his costume, attributing their length to the wardrobe department attempting tio remind him that the author of the work in question was a certain “Longfellow”. The telling of the title story, however, is played almost entirely for the dramatic, as was custom for the series when Magoo assumed a role. Animation is simple but effective, with some nice atmospheric background work, as was a specialty of Levitow’s productions. The tale encompasses multiple events, including both the Boston Tea Party and the midnight ride. General Gage is oddly portrayed as an indecisive and gullible type, while his lieutenant does most of the conniving. Magoo gets to play one scene comedically, using a jug of hard cider borrowed from a fellow patriot to learn news of the British’s means of attack. Pretending to be drunk, he stumbles over to a British soldier and offers him a friendly drink. The disgusted soldier states he’ll get all the rum he wants when he gets aboard ship – and thus spills the beans that the attack will be by sea. History is particularly rewritten, as Magoo himself hangs the lanterns in the Old North Church, then also rows across the river to take on the ride on the other side (rather an inefficient waste of time, when a simple signal to someone by lantern would have saved the time of the boat ride). The ride is presented in straightforward fashion, and ends with the shot heard round the world and an American flag dissolving into the heavens as the new day’s sunrise.

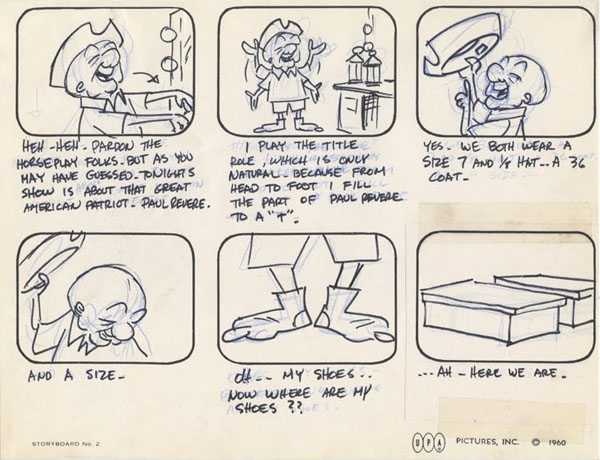

Can’t find this episode online – except in Spanish – but I think you get the idea from the synopsis above and this part of the storyboard.

Son of Liberty (Art Clokey, Gumby, 11/15/66) was one of four Gumby special historic episodes produced in collaboration with Lakeside Toys (then the distributor of the commercially successful Gumby and Pokey poseable action figures). While riding skateboards in the toy shop, Pokey overshoots a turn and winds up headfirst in a history book on the American Revolution. There, he overhears General Gage giving orders for a secret detachment of 800 British troops to capture John Hancock and Samuel Adams and seize the ammunition of the Sons of Liberty. Gumby joins in the eavesdropping through the general’s wall, then both disappear back out the cover of the book, with intent of finding Paul Revere to warn the minutemen. They are overheard, and a British soldier also exits through the book cover, narrowly missing Gumby with a rifle shot. Gumby and Pokey play a game of cat and mouse among the toys as more soldiers emerge hunting for the spies. They climb into a jeep and try to outspeed the soldiers back to the book, but find the book now being guarded with a large cannon, a shot from which blasts their jeep into a charred hulk. An aerial assault on the soldiers in a toy plane also fails. Gumby finally pulls out an old standby from earlier episodes of the series – his pet groobee – an insect that builds wooden crates around everything it sees. Releasing the groobee from its cage, Gumby stands back to watch the fun, as the insect intercepts a fired cannonball in midair, bringing it to a halt with a crate built around it. In no time, the soldiers, as well as the cannon, are securely crated and ready for shipment back to King George. Gumby and Pokey pop their heads back into the book, finding the chapter where Revere’s silversmith shoppe is located. Gumby gives news of the planned attach to Revere, and is rewarded with a genuine Son of Liberty badge. Pokey suggests that now they get out of here, but Gumby says he’d like to stay and see the fireworks. Pokey states that British cannonballs and he just don’t get along, and heads home. Gumby’s bravery quickly wanes too, as his eyes pop at the approach of just such a cannonball, which leaves a gaping hole in the wall mere seconds after Gumby escapes through it, as the words “The End” appearing in the vacant hole.

In Gumby Crosses the Delaware (11/16/66), Pokey is chef at a Gumburger stand, and Gumby is communicating with him long distance by playing with a set of walkie-talkies, one of which is fastened to a collar around Pokey’s neck. Pokey sends a message for assistance, claiming that a beatnik is hanging around the stand and trying to get a free handout. When Gumby arrives, he hears the man (wearing a motley military uniform) mention needing food for his friends at Valley Forge, amd recognizes him to be one of General Washington’s soldiers (presumably stepping out of a history book, as was the usual custom for the series). Gumby okays a free shipment of supplies for all the men, and he and Pokey accompany the soldier in a toy jeep back to Valley Forge. The men’s appetites appeased, Washington announces that the time is right for an attack on Trenton. But he wishes he knew what the Hessian forces were up to to be sure he has the element of surprise. Gumby volunteers the services of himself and Pokey, offering to use the walkie-talkie set to have Pokey infiltrate Trenton as a long-distance spy. “Wonderful magic if you can do it”, Washington replies.

Pokey is shown the way to Trenton – six mules upstream by way of the Delaware River. The river is covered in floating cracked ice floes. Pokey says no thanks, and that he’ll wait until someone builds a bridge. Gumby insists all he has to do is hop from floe to floe to get across. A slightly sullen Pokey realizes he can’t let down the father of our country, and, in a now politically incorrect remark, references “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” with the line, “Just call me little Eliza Pokey.” He proceeds to hop, and eventually makes it across. Coming across two Hessian guards, the naive Pokey presumes they are country shepherds, and asks for directions to Trenton. The mock-Germanic speaking Hessians are astounded at encountering a talking horse, and decide he’d make a great mascot for their General. Pokey realizes he’s “really put my hoof into it”, and is taken along to headquarters. Meanwhile, Gumby is boarding a small boat with General Washington, and radios to Pokey for a status report. At Trenton, Pokey is being presented to the General, just as Gumby’s call comes in. Pokey tries to whisper into his collar that he can’t talk now, but Gumby loudly insists that General Washington needs a report. The Hessian General is amazed, not only at the talking horse, but the talking box. As Gumby continues to blurt out more information over the radio, mentioning both that he and Washington are in the middle of the Delaware river and need to know what the Hessians will be doing when they attack in the morning, the Hessian general thinks it’s the most funny and entertaining story he’s heard in years. What will they be doing in the morning? The Hessian general laughs, “We’ll be sleeping in late!” Pokey is dying a thousand deaths, as nothing he can say will shut Gumby up, but the Hessians are absolutely convinced the horse and his box are great comedians. They bring him inside to show off to the troops over a dinner of weinerschnitzel, with the General bragging about the horse’s “funny story about General Washington. It’ll kill you!” That night, Pokey is locked in with the Hessian general in his quarters. In the morning, Gumby and Washington arrive, and after more blurting out by Gumby over the walkie talkie about their arrival, busts in the door of the Hessian General’s quarters. Hearing Gumby address Pokey in the flesh (or clay), the Hessian General realizes it’s “the same voice” from the box – and jumps out the window. Gumby frees Pokey, but Pokey suggests that perhaps they’d better keep a British flag at their Gumburger stand in the future just in case. Gumby asks why, since Washington won the battle. Pokey replies, “With our help, next time he may not be so lucky.”

Pokey is shown the way to Trenton – six mules upstream by way of the Delaware River. The river is covered in floating cracked ice floes. Pokey says no thanks, and that he’ll wait until someone builds a bridge. Gumby insists all he has to do is hop from floe to floe to get across. A slightly sullen Pokey realizes he can’t let down the father of our country, and, in a now politically incorrect remark, references “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” with the line, “Just call me little Eliza Pokey.” He proceeds to hop, and eventually makes it across. Coming across two Hessian guards, the naive Pokey presumes they are country shepherds, and asks for directions to Trenton. The mock-Germanic speaking Hessians are astounded at encountering a talking horse, and decide he’d make a great mascot for their General. Pokey realizes he’s “really put my hoof into it”, and is taken along to headquarters. Meanwhile, Gumby is boarding a small boat with General Washington, and radios to Pokey for a status report. At Trenton, Pokey is being presented to the General, just as Gumby’s call comes in. Pokey tries to whisper into his collar that he can’t talk now, but Gumby loudly insists that General Washington needs a report. The Hessian General is amazed, not only at the talking horse, but the talking box. As Gumby continues to blurt out more information over the radio, mentioning both that he and Washington are in the middle of the Delaware river and need to know what the Hessians will be doing when they attack in the morning, the Hessian general thinks it’s the most funny and entertaining story he’s heard in years. What will they be doing in the morning? The Hessian general laughs, “We’ll be sleeping in late!” Pokey is dying a thousand deaths, as nothing he can say will shut Gumby up, but the Hessians are absolutely convinced the horse and his box are great comedians. They bring him inside to show off to the troops over a dinner of weinerschnitzel, with the General bragging about the horse’s “funny story about General Washington. It’ll kill you!” That night, Pokey is locked in with the Hessian general in his quarters. In the morning, Gumby and Washington arrive, and after more blurting out by Gumby over the walkie talkie about their arrival, busts in the door of the Hessian General’s quarters. Hearing Gumby address Pokey in the flesh (or clay), the Hessian General realizes it’s “the same voice” from the box – and jumps out the window. Gumby frees Pokey, but Pokey suggests that perhaps they’d better keep a British flag at their Gumburger stand in the future just in case. Gumby asks why, since Washington won the battle. Pokey replies, “With our help, next time he may not be so lucky.”

The Story of George Washington (Paramount, Noveltoon, 1965 (date unknown) – Jack Mendelsohn, dir.) is told entirely in visual style resembling the scrawl of the drawings of a grade-schooler – based on Mendelsohn’s comic strip Jacky’s Diary. Paramount apparently hoped to spin a regular series out of this idea, christening same as “Jacky’s Whacky World” in the main titles and producing one other entry. Ultimately, the concept (with the later exception of Shamus Culhane’s “Fractured Fables” series starting with 1967’s My Daddy, the Astronaut) took no further flights – though that seemed to make little difference to the animators, as the ever-decreasing budgets of Paramount productions made many a subsequent episode look like childhood scrawl when they weren’t even trying! (Was Paramount solving its budgetary problems by hiring child labor?) The film is little more than a montage of spot gags and verbal and visual puns (“Honesty is the best polly seed.” George “mustard” his troops – by coating his soldiers, and their hot dogs, in the condiment. The “tea tacks” gag is ripped off from Yankee Doodle Bugs, as is the “wait a minute” minuteman gag from Hysterical Highspots in American History.) George’s history-making exploits finally account for why people like “to collect his picture” – depicted on a one-dollar bill. The film develops at best only occasional smiles and not belly-laughs, and all in all is not “my cup of tea”.

Next Week: Oh, Magoo, you’ve done it again!

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

There’s a Heathcote Road I occasionally have to take. I invariably refer to it as “Hector Heathcote Road”. “Stop calling it that!” says my wife. But I can’t! The Hector Heathcote cartoons are funnier than I remember.

A memorable musical segment on “The Alvin Show” had the Chipmunks, dressed in Continental Army uniforms with periwigs and tricorn hats, singing a version of “Yankee Doodle” in which the legendary dandy stuck a feather in his hat “…and called it spaghetti!”

It’s impressive to note how much fun these animators had in playing around with American history. Shows that at some level the writers had at least a working knowledge of the key events and personalities.

I was briefly acquainted with one of the animators who worked on the Mr. Magoo series. He was highly proud of the Famous Adventures, considered it one of the highlights of how the character was used. This individual actually valued the Famous Adventures series more highly than its predecessor, the Christmas Carol special–which he had forgotten about until I asked him questions about it. Even then, he said it wasn’t as good as the series–which I thought was an interesting take, as most reviewers consider the special to be better. But that is taking pride in one’s work. To me it’s refreshing that he could look back on the series with so much pride so many years later.

I remember watching the Hector series when I was a kid–I believe that is how I first became acquainted with the concept of the Minute Man.

It’s fascinating how much they could pack into these short cartoons.

Peabody and Sherman had two other adventures during the War of Independence, both in Season 2 (1960). In “Paul Revere”, they find the famed silversmith unable to sound the alarm throughout the countryside — because his horse is merely a statue. Peabody recommends that he ride a pig instead, but Revere has difficulty controlling the animal. Meanwhile, a famous military leader, described by Peabody as “a certain general who shall remain nameless” (hint: his profile is on the quarter), has come to Massachusetts on a recruiting drive. Peabody warns him about the British, but the general refuses to believe any report unless it comes from Paul Revere himself; and in any case, he can’t mount a defence until he builds up a bigger army. Peabody tells him that in this colony, he can only attract new soldiers with the “Boston Back Bay battle cry” — in other words, “SOO-EY!” Revere quickly shows up on his pig, and the cry also attracts a long queue of recruits in just sixty seconds. “I’d call them Minutemen,” says Peabody. (cue timpani glissando)

In “The Battle of Bunker Hill”, the British confound the order “Don’t shoot until you see the whites of their eyes” by the simple expedient of wearing sunglasses. At four o’clock, as the British stop for tea, the lieutenant in charge tells Peabody that his troops cannot fire unless either the British remove their sunglasses, or he receives a countermanding order from Headquarters (an order that will take at least a week to arrive, because Headquarters is in New York). While the lieutenant heads to the Big Apple, Peabody places a sign over a hole in a fence reading “Don’t look through here”; and when one by one the redcoats, naturally, do so, Sherman sprays their sunglasses with white paint. Then, posing as eye surgeons, Peabody and Sherman meet with General Burgoyne and tell him that an outbreak of “spotsitis” has afflicted his troops. He then uses a horseshoe magnet to remove each soldier’s sunglasses, and lo and behold, the spots before their eyes disappear. At this point, however, the lieutenant returns from New York (“How did you get back so fast?” “I hit the signals just right!”) with a new order: “Don’t fire until you see the glare of their sunglasses.” Peabody goes back to Burgoyne and tells him that the only way to prevent a recurrence of spotsitis is by wearing sunglasses. The general orders his men to don their shades, and history is back on track. Peabody’s final pun — that what they did was a “frame-up” — is nearly as groan-worthy as his comment about Cornwallis.

And then there’s The Flintstones….

In the fifth season episode “Time Machine” (15/1/65), the Flintstones and the Rubbles are taking in a science fair; and, having left Pebbles and Bamm-Bamm at a day care centre run by a handy “Rocktopus”, they decide to take a ride in an experimental time machine. It transports them into the future, where they encounter the Emperor Nero, Christopher Columbus, the Knights of the Round Table, and the 1964 World’s Fair — as well as Benjamin Franklin, flying his kite in front of Independence Hall. Franklin welcomes them to Philadelphia and apologises for yawning, as he had been up late the night before. “Oh, that’s not good,” Wilma tells him. “You know: Early to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise.”

“You don’t say! That’s very interesting,” Franklin says. “Perhaps I’d better write that down. Would you mind holding my kite?” Fred takes the string while Franklin jots down a series of aphorisms uttered by Wilma, who has something of an Amos Mouse role in this scene.

Finally, lightning strikes the kite and gives Fred a nasty jolt. When Wilma, Betty and Barney try to help him, the electrical charge is transmitted to them, surrounding them with a shimmering yellow aura as they jerk and twitch like Rock Roll after a pickled dodo egg binge.

“My goodness! So that’s how electricity works!” Franklin observes. “I’d better write that down, too!”

So… since the HECTOR HEATHCOTE shorts were produced by CBS’ Terrytoons, and the Saturday morning “Hector Heathcote Show” aired on NBC from 1963 to 1965… wouldn’t that make the show one of the first (if not the first) programs produced by one network to air on a different network?

Re Hector Heathcote, the name “Heathcote” comes from the history of Scarsdale, NY, the town next to New Rochelle, NY, where Terrytoons was headquartered. Scarsdale was originally known as “Heathcote Manor,” named after one Caleb Heathcote, who held a royal patent on the land in the 17th century. The name has survived as that of a wealthy neighborhood in Scarsdale. It must have been something of an inside joke at Terrytoons to name a hapless character after a nearby ritzy suburb.

While not a cartoon, as a work by a frequent contributor to animated cartoons, I feel “Stan Freberg presents The United States of America” (1961), along with its 1996 sequel, deserves an honorable mention here.

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=OLAK5uy_muWoGEKWXdfousCL8Yx7kT9mN_DJOgCw0

You’re ahead of the game. Wait until next week!

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0295090/

mentions that Heathcote was a time-traveling scientist, in press releases. http://www.toonopedia.com/heathco.htm also repeats this claim.

I’ve never seen the network show, so I’m unable to confirm or deny this. Are there any opening/closing credits for the show available?

I haven’t found any original titles to the Hector Heathcote Show online, just modern reconstructions (with many misspellings). While the Big Cartoon DataBase also repeats the claim that Hector was a “time-traveling scientist”, this is not the case. Like other cartoon characters, he simply turns up in various historical periods; and he works at a variety of different jobs (e.g., blacksmith, bartender, messenger boy), but never as a scientist. So this claim appears to be a widespread misconception.

As you noted in your earlier Animation Trail “Countdown to 2020: Better Late Than Never”, Felix the Cat, while traveling back through time in “Stone Age Felix”, briefly encounters Benjamin Franklin and his kite in 1750 Philadelphia.