The truth, as always, is far different. The thought of eliminating his competition had never occurred to Mel who, at first, was simply after any income he could make as a crazy voice man. And several years later he was far too successful for such unprofessional shenanigans. Yet this silly rumour has become more and more accepted since the cartoons began airing endlessly on TV from the mid-1950s, when viewers who saw his name understandably thought, “Gee, this Mel Blanc guy does EVERY voice: hey, that must be him doing Granny, or that funny singing frog, or that Road Runner.”

Another factor feeding the story of Blanc being high-handed with colleagues was actor Stan Freberg. In his later, dottier years he compounded the situation by insisting Mel getting his name on-screen was morally bankrupt (“illegal”), and Blanc should have made sure his fellow actors like Arthur Q. Bryan got equal credit. With these wrongheaded falsehoods now being parroted on Facebook posts by cartoon newbies I intend to finally clear them up.

First, some background. It should be noted that voice artists were, and still are, specialty people for hire. Classic era movie casting departments referred to them as “extra talent” i.e., non-contract freelancers. With the introduction of sound, early musical cartoons used professional singers who began being heard on soundtracks from the 1931-32 season. Most spoken dialogue was minimal, and mainly handled by in-house employees like Rudy Ising or Dick Heumer. Rare talents like Pinto “Goofy” Colvig or Clarence “Donald Duck” Nash, who showed actual comic talent along with appealing trick voices and barnyard imitations, were soon being retained and nurtured.

Professional radio talent was slowly hired from 1930, at first not on a large scale, often due to budget considerations. In 1933, Disney’s Three Little Pigs was released and proved a sensation. Colvig had recommended his silent-era comedy colleague Billy Bletcher when Disney needed a truly distinctive villain voice for the Big Bad Wolf. Disney’s Silly Symphonies became increasingly lavish and cartoons like Who Killed Cock Robin? began featuring a range of outside talent.By 1936 as theatrical cartoons gained in verbal and comic sophistication and the animation became more polished and accomplished, they relied far less on the early gimmick of musical synchronization. The singers used were reduced to a chorus or two and the hiring of facile radio comedy voices began to be emphasized. At Leon Schlesinger’s studio, standout creative talents like director Tex Avery had the services of a rare studio comic in Ted Pierce, gag man and natural actor, who was used as an opening off-screen narrator in The Village Smithy. Avery was quick to note that his narrator gimmick was soon being copied by Disney.

Schlesinger’s first big star was Porky Pig who was originally spoken by a real-life stammerer, a makeup assistant and bit player named Joe Dougherty. Treg Brown, the studio’s inventive sound man was the first and virtually only editor to pitch-change cartoon voices and give them an extra-funny speeded up quality…Dougherty’s impediment sounded far cuter when sped, while another sound mimic, Count Cutelli, recorded the first stuttering “That’s ALL Folks.” But the ongoing popularity of Porky demanded a much better actor with comic sense and real vocal flexibility… what was needed was a controlled stutter.

It was at this stage that Mel Blanc, struggling young dialect specialist, entered the picture. After moving to Los Angeles, he had begun working for various local radio stations including comedy shows originating from Warner’s own KFWB, housed on the same Sunset Boulevard lot as the cartoon studio. The directors had already begun using some radio voices in their cartoons, and in late 1936 Blanc auditioned.

Treg Brown recorded his tryout session, and was impressed enough to quickly recommend Mel to Lantz, Mintz and MGM. Blanc’s voice test with its crazy yells and comic dialects stood out…a lot of the actors being hired were adequate, some were proven talents like Billy Bletcher, but Mel had a natural comic flair that many others lacked.

At this stage, though, Blanc was just one of a band of reliable radio funny folk with trick voices and party piece comic characters…Joe Twerp, Bletcher, Don Brodie, Elvia Allman, etc. Schlesinger was fortunate enough to house some of the industry’s top young gag-men, and Avery worked with this crazy group to create his first really successful character, Daffy Duck. Fortuitously, Blanc’s first major cartoon assignment was Porky’s Duck Hunt in which he debuted his new and improved Porky as well as the earliest incarnation of Avery’s insane Daffy.

At this stage, though, Blanc was just one of a band of reliable radio funny folk with trick voices and party piece comic characters…Joe Twerp, Bletcher, Don Brodie, Elvia Allman, etc. Schlesinger was fortunate enough to house some of the industry’s top young gag-men, and Avery worked with this crazy group to create his first really successful character, Daffy Duck. Fortuitously, Blanc’s first major cartoon assignment was Porky’s Duck Hunt in which he debuted his new and improved Porky as well as the earliest incarnation of Avery’s insane Daffy.

It was soon apparent that Blanc’s voice work, which complemented the wildly silly material supplied by Tex and the other gagsters, had a uniquely “cartoony” quality. With his musical background, he could even sing in his screwball voices. The Schlesinger cartoons had begun getting positive reviews from exhibitors for their advances in color, improved animation and mostly better comedy, and Mel would prove their perfect fit.

As early as mid-1937 Blanc was being hired for virtually every Warner cartoon, at first in bits but also as the studio’s leading star Porky, who was just kicking off a new series at Leon’s second division cartoon wing, Ray Katz Productions. The young Bob Clampett was the first director to use Mel as sole actor supplying every voice in one cartoon (in entries like Porky’s Badtime Story). The old vocal groups soon took a back seat, and Mel and his radio co-stooges like Harry Lang, Phil Kramer and Sara Berner were soon dominating West Coast animation voice work. Mel and Dave Weber, a dialect coach and mimic recently transplanted from New York, became two of the most commonly heard voices in LA-originated cartoons of the late 1930s. Mel’s timing was certainly good…as he ascended so did the confidence and abilities of the Warner directors, animators and story staff.

Tex Avery kept excelling too, and he took the young voice man with him. After Porky’s Duck Hunt, he and Blanc scored a big success with Daffy Duck and Egghead. And in 1940, following the enormous reaction to A WILD HARE and Blanc’s marvellous new rabbit voice, as coached by Avery, the industry took notice. He was also noted by his employers: his continuing quality work playing studio stars Porky and Daffy convinced Schlesinger and Henry Binder that it would be highly advantageous to have Blanc under contract for their exclusive use. And not before time: Hardaway and Lantz already had him doing their new Universal star Woody Woodpecker, MGM had used him as a lead voice in some of their cartoons, and Frank Tashlin nabbed Blanc for his new Fox and Crow starrer at Screen Gems just days before he would no longer be available.

In the spring of 1941 Mel’s status changed forever. On April 25th, Daily Variety noted, “Mel Blanc, the gravel-voice in Bugs Bunny Merrie Melodies cartoon, has been signed to term contract by Leon Schlesinger, setting a precedent in the animated cartoon field.” His signature was appended to a two-year “Artists – Stock Talent” deal. Blanc’s salary at the start was $65.00 per week for 50 weeks, and the piece of paper had no other hold on his services. Daily Variety added, “Contract does not conflict with Blanc’s radio engagements. His first impersonation for Schlesinger was Porky Pig…” This meant that while Mel could no longer speak for cartoons made at other animation houses in Hollywood, he was still free to do any radio or live action film work (his character voices are heard in a WB live action short called Sniffer Soldiers from 1942).

In the spring of 1941 Mel’s status changed forever. On April 25th, Daily Variety noted, “Mel Blanc, the gravel-voice in Bugs Bunny Merrie Melodies cartoon, has been signed to term contract by Leon Schlesinger, setting a precedent in the animated cartoon field.” His signature was appended to a two-year “Artists – Stock Talent” deal. Blanc’s salary at the start was $65.00 per week for 50 weeks, and the piece of paper had no other hold on his services. Daily Variety added, “Contract does not conflict with Blanc’s radio engagements. His first impersonation for Schlesinger was Porky Pig…” This meant that while Mel could no longer speak for cartoons made at other animation houses in Hollywood, he was still free to do any radio or live action film work (his character voices are heard in a WB live action short called Sniffer Soldiers from 1942).

Interestingly for the first two years of his contract Mel’s fee of 65 bucks per weekly cartoon recording was less than the session fee paid to the more-established radio comic Arthur Q. Bryan (Elmer Fudd), who got a negotiated fee of $75.00 a session, above the then-scale payment, and not bad pocket money in 1941. And Bryan upped his fee with each passing year.

The cartoons kept improving in the new decade, and Mel’s work became still more distinctive. Leon’s starring characters of Bugs, Porky and Daffy were now being singled out by both exhibitors and in fan-mail as superior to standard bearer Disney’s short cartoons.

When it came time to renew Mel’s contract his salary was increased to $75.00 per week for another guaranteed 50 weeks per year. The second contract was signed in April of 1943 to take effect on the 24th, and this time it would be for three years. Importantly for Blanc, it allowed him to exercise any contract options before one full year had elapsed. And before that next option signing occurred in 1944, the issue of giving Mel screen credit had been discussed and agreed to.

Giving an unseen dubbing artist name billing was definitely a new wrinkle in Hollywood. Producers followed Disney’s long-stated policy of anonymity. Walt’s reasoning was that audiences should fully believe in the animated onscreen animals, and publicising a real person behind a microphone would destroy the element of fantasy. (That, and the possibility that an actor with his name on screen might just demand more money!)

Of course in Mel’s autobiography and in countless radio / TV interviews he gave from the late 60s, he embellished the “story” of his screen credit. Explaining that wife Estelle made most of his financial decisions, he writes “At my better half’s urging, I marched into Leon Schlesinger’s office to demand a salary increase. It wasn’t going to be easy because the producer was notoriously tightfisted with money.” He goes on with his patented narrative: Leon’s response was, “What do you want more money for, Mel? You’ll only have to pay more taxes.” To which Mel counters, “Well, if you won’t give me a raise, how about at least giving me a screen credit?”

It doesn’t help that Mel’s chronology is a couple of years too early, and his discussion with Leon occurs before Mel even did Bugs Bunny’s voice in 1940. But that book later has Mel signing his exclusive deal with Leon in 1949 (eight years after it actually happened), and not until he’d done some thirty Woody Woodpecker cartoons…he actually completed just four. As Bob Clampett once quipped, “Mel was the greatest cartoon voice and the worst cartoon historian.”

It doesn’t help that Mel’s chronology is a couple of years too early, and his discussion with Leon occurs before Mel even did Bugs Bunny’s voice in 1940. But that book later has Mel signing his exclusive deal with Leon in 1949 (eight years after it actually happened), and not until he’d done some thirty Woody Woodpecker cartoons…he actually completed just four. As Bob Clampett once quipped, “Mel was the greatest cartoon voice and the worst cartoon historian.”

The reality is that when his next renewal was signed, under the Options paragraph it stated the Producer was to give Mel “screen credit for Bugs Bunny’s voice in all Bugs Bunny pictures that Employee’s voice is recorded. Such credit is to appear on those pictures recorded by Employee during the term of this contract.” It was obvious by 1943 that Bugs in particular was already a highly prized cartoon property.

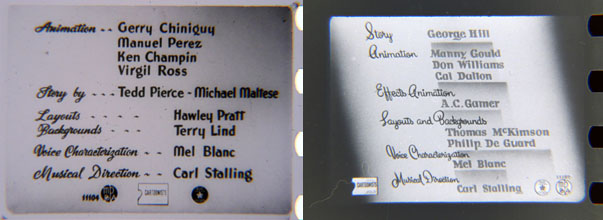

And so over the next year Mel’s name finally appeared on-screen, after the distinguished sounding “Voice Characterization,” at first in just his Bugs Bunny cartoons beginning with Little Red Riding Rabbit released on January 1, 1944. While every non-Bugs cartoon still bore no voice credit, Mel’s name appeared on the following releases in 1944: Bugs Bunny and The Three Bears, Bugs Bunny Nips The Nips, Hare Ribbin’, Hare Force, Buckaroo Bugs, The Old Grey Hare and Stage Door Cartoon.

Contrary to latter-day comments by Freberg, Chuck Jones and June Foray, Mel was not responsible for other people’s careers. And in any event, had Bryan, Bletcher, Bea Benaderet or any other voice performer asked their agent to negotiate screen billing, the odds are they would have been unsuccessful. Aside from Bryan, considered a one-trick pony, the other voice talents were essentially day players who didn’t speak for any regular or star characters. The only non-Blanc character of note in this period was Elmer Fudd but he only appeared sporadically. Besides, Arthur Q. was so busy with Fibber McGee and other national radio shows he may not have felt it was worth seeking credit. Most actors regard each gig as a gift and he might have thought “Who knows, maybe this’ll be the last time they use this Elmer loser!”

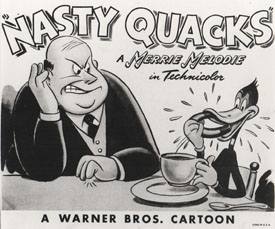

Blanc’s next contract update was in March, and before he exercised his yearly option, the credit paragraph was amended to specify that Mel’s name would now appear on “Bugs Bunny as well as Porky Pig and Daffy Duck cartoons.” That meant that throughout 1945 Mel’s name was emblazoned on-screen in Herr Meets Hare, The Unruly Hare, Hare Trigger, followed by his first non-Bugs Bunny credit for the Porky cartoon Wagon Heels, Hare Conditioned, Hare Tonic, and in his first known credit for a Daffy entry, Nasty Quacks.

Blanc’s next contract update was in March, and before he exercised his yearly option, the credit paragraph was amended to specify that Mel’s name would now appear on “Bugs Bunny as well as Porky Pig and Daffy Duck cartoons.” That meant that throughout 1945 Mel’s name was emblazoned on-screen in Herr Meets Hare, The Unruly Hare, Hare Trigger, followed by his first non-Bugs Bunny credit for the Porky cartoon Wagon Heels, Hare Conditioned, Hare Tonic, and in his first known credit for a Daffy entry, Nasty Quacks.

(Researching this chronology is a pain thanks to those execrable Blue Ribbon cartoons…I am unsure if the earlier Daffy from 1945 – Ain’t That Ducky – features Mel’s name, although I suspect Nasty Quacks was indeed the first Daffy-with-credit because it fell in the new season’s releases covered by the contract; I also note that the next Daffy released, Book Revue did not feature Mel’s name…there are two reasons: production had commenced on Book Revue before Nasty Quacks, and as brilliant as Blanc’s and Daffy’s performances were, the little black duck was still a glorified cameo in this books-come-to-life entry.)

The next option renewal following Blanc’s 1945 updated agreement states the same screen credit as before for each Bugs, Daffy and Porky release, but this time around adds “and in all pictures in which the Employee’s voice characterization is used for a major portion of the motion picture.”

And so in 1946, Mel’s name was seen in Baseball Bugs, Hare Remover, possibly in Daffy Doodles (a Blue Ribbon reissue), and for the first time in a cartoon which featured none of the regular Warner stars: Hush My Mouse. And it’s from that point that Mel’s name appears in virtually all the studio’s cartoons to come. The exceptions in 1946 were the earlier Baby Bottleneck (featuring Porky and Daffy) and Bacall To Arms, both of which very likely had their credit titles prepared before the new rider in Mel’s contract.

The only remaining 1946 cartoons for which we need to confirm Mel’s screen credit following Hush My Mouse are those Blue Ribbon reissues which were vandalized by being shorn of all original opening titles. We can assume Blanc got screen credit on all the releases that he contributed voices to (Tweetie Pie and Mouse Menace, whose original titles still exist, confirm this).

The credits from Tweetie Pie (left) and Mouse Menace (right), off the original negatives. Thanks, David Gerstein.

More about Tweety’s titles – click here.

Let’s hope the real titles can be found for Daffy Doodles, The Eager Beaver, Of Thee I Sting (unlikely, as Mel is not heard in this), Walky Talky Hawky, Fair and Wormer, The Mouse-Merized Cat, Mouse Menace,and Roughly Squeaking. From 1947, however, I can state with confidence that Mel received voice credit all the way to the end of the Warner cartoon releases in 1969.

By now Blanc had more clout. His 1946 contract also strictly specified that his cartoon recordings be scheduled so as “not to conflict with his radio work, and at the same time, enable himself to render his services to Producer” while an extra Paragraph 19 was added to include Warner Bros. payment to Mel of “20% of net royalties received from the sale of Phonograph Records,” as the deal with Capitol was finalized. And other terms improved: he was now given eight weeks off each summer, two with full pay (now at $125 a week).

Of course having his name at the opening of highly popular theatrical cartoons on a huge Technicolor screen in the town of Hollywood guaranteed industry notice, and Mel was now able to ask for better terms as a radio stooge on his regular shows, Abbott & Costello, Judy Canova, Burns & Allen and Jack Benny. Jack loved Mel’s scene-stealing ability and from 1943 Mel began appearing more and more on the Benny program. He soon became a weekly fixture and the recipient of Benny’s real-life generosity. Blanc revealed he was paid far above scale for the Benny gig. The Jack Benny association did as much as his cartoon billing to make Mel famous enough to star in his own one-season Mel Blanc Show for Colgate-Palmolive on CBS in 1946-47.

By 1947 Mel’s cartoon salary grew to a weekly payment of $175.00, increasing the following year to $200.00 for each successive year through 1952. Frustratingly I found no contracts beyond the 1947 document, so we can only presume his management may well have negotiated more raises for his Warner toons post-1952. This was good money back then, particularly when combined with his radio fees and, in the burgeoning TV era, the advent of commercial residuals.

It says much of Blanc’s enormous native talent that he was considered important enough to receive screen billing. The only other examples of any short cartoons to display a voice credit in the 1940s were Lantz’s use of radio gossip host George Fischer in the 1940 Recruting Daze, and one of two 1945 releases (Sliphorn King Of Polaroo) featuring quirky Hans Conried, who was also billed in later cartoons for UPA and MGM. Famed Calypso singer, Sir Lancelot was credited in Columbia’s The Disillusioned Bluebird, while Stan Freberg received billing in the once-off Republic entry It’s A Grand Old Nag made by former Warner director Bob Clampett. An occasional distinguished New York radio voice was credited in Famous Studios entries – such as Frank Gallop and Ken Roberts – even though the great “Popeye” triumvirate of Jack Mercer, Jackson Beck and Mae Questel was never billed!

Overall, the cartoon voice field was Mel’s by a country mile, but that other great fallacy – that he requested screen credit just to have the game all sewn up so that other actors couldn’t be promoted – is not only plain wrong but a slur on his reputation. If Mel had been that spiteful, let alone that powerful, he would have had real enemies. And he would have run into them each week on radio calls. According to Mel’s son Noel, his father and Arthur Q. Bryan were actually friends in real life, and Mel had acted weekly in Bryan’s own radio vehicle Major Hoople.

Blanc was only human and he could occasionally be self-protective. Some people like Bill Scott found him a bit aloof. But beyond some actor-ish sniping and jealousy, most of the industry applauded Mel for his achievements. Although Mel’s screen billing continues to fuel inaccurate cartoon history, it was essentially due to his excellent work and, in retrospect, seems entirely fair.

For other actors, the 1950s saw few changes. With the exception of Jim Backus receiving credit once Mr. Magoo took off, and UPA occasionally affording screen billing to select actors, most other voice artists simply had to wait until the situation changed. Walt Lantz began allowing his voice talents credit, at first with Sara Berner for Chilly Willy in late 1953, then Frank Nelson for Dig That Dog and non-relative Dick Nelson for Broadway Bow-Wows in 1954. Dal McKennon was the first to receive consistent billing in each Lantz release from late 1955 onwards. June Foray and Daws Butler were grateful to Lantz for giving voice credits several years before it became accepted industry practice.

The one Warner exception was Freberg’s credit in 1957’s Three Little Bops, but by then Stan was a big recording name. In the early 60s a Screen Actors Guild ruling resulted in cartoons finally listing other voice artists from late 1961, over thirty years after sound films began! And starting with the 1966 entry Muchos Locos Mel even got his own “starring” voice credit card, followed by other actors’ names on a separate card in smaller font. Of course the cartoons were so diminished by then it meant less than it had earlier.

The new medium of TV cartoons began crediting actors early in the 1950s, and all the Hanna-Barbera shows, starting with Ruff & Reddy in 1957, gave prominent credit to their voices, aware of their obvious importance in the new age of planned animation. This meant that an artist like Daws Butler was soon as well-known for animation voice work as was Mel.

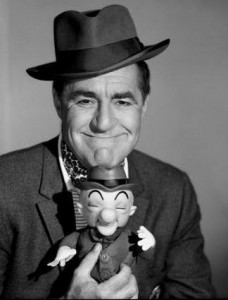

In this candid snapshot, Mel Blanc records a commercial spot at Quartet Films in the 1950s.

I hope this overlong article finally clarifies the fact that Mel Blanc was the first voice person to be signed to an exclusivity deal, and that it can put to rest some long-running falsehoods and wrong assumptions: firstly that Mel had his name on every Warner cartoon of the 1940s (in reality it was more gradual and limited to certain characters’ cartoons over the first three years, 1944-47), and secondly that his on-screen billing had been orchestrated by Mel with the malicious intent of keeping all other voice people anonymous. As I said, in real life such bullying machinations would have seen Mel reprimanded and possibly fired, but it’s the sort of gossipy nonsense that keeps a new generation of know-nothing fanboys mindlessly fulminating some seventy years later.

Sources: Daily Variety clipping (Herrick Library); various contract documents and sound recording logs (USC Warner Bros. Archives); the book “That’s not all Folks! (My Life in the Golden Age of Cartoons and Radio)” (1988) by Mel Blanc and Philip Bashe; author’s telephone interviews with Stan Freberg, Chuck Jones and June Foray. Various audio and print interviews with Mel Blanc; and of course the many cartoons featuring Mel.

KEITH SCOTT is slowly but surely completing a historical survey of Golden Age cartoon voices for an eventual book.

Keith Scott is a voice actor, impressionist and animation historian. Scott provided the voice for Bullwinkle J. Moose in the 2000 motion picture The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle (for which he had been specially flown to the United States several times) and did the voice of the narrator in George of the Jungle and George of the Jungle 2. An expert on the history of Jay Ward Productions, Keith authored the book The Moose That Roared: The Story of Jay Ward, Bill Scott, a Flying Squirrel, and a Talking Moose (St. Martin’s Press, 2000).

Keith Scott is a voice actor, impressionist and animation historian. Scott provided the voice for Bullwinkle J. Moose in the 2000 motion picture The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle (for which he had been specially flown to the United States several times) and did the voice of the narrator in George of the Jungle and George of the Jungle 2. An expert on the history of Jay Ward Productions, Keith authored the book The Moose That Roared: The Story of Jay Ward, Bill Scott, a Flying Squirrel, and a Talking Moose (St. Martin’s Press, 2000).

Great post.

Art imitates life: There’s at least one episode of Jack Benny’s radio show which has Mel Blanc’s “wife” (I think it’s Bea Benaderet) negotiating his employment contract. (Jack gets hit on the head with a can of tomato juice and starts spending money; Mel’s wife extracts a better deal. Then Benny gets hit by another can and he returns to his thrifty ways.)

Title cards with credits exist for Ruff and Reddy? I’d like to see them some time.

Ruff and Reddy was a Screen Gems production, with Hanna-Barbera only supplying the Ruff and Reddy cartoons. The rest of each show was live action, coupled with an old Columbia theatrical.

They don’t. The only credit of visual significance was during the opening titles of the cartoons themselves (“Produced and directed by Joseph Barbera and William Hanna). One source says that Dan Gordon and Charles Shows did the stories and storyboards.

Great article, Keith. Thank you!

Terrific effort in research and writing and NOWHERE near “overlong”. This makes me look forward to the eventual book on cartoon voices.

Looking forward to the eventual book, Keith! It’d be great if there could be some kind of multimedia companion (this site? your own blog?) where readers could quickly listen to samples of the voice artists you catalogue.

Mel’s radio work for Disney is rarely mentioned.He worked in “Mickey Mouse’s Theater of the Air” along with Clarence Nash and Billy Bletcher.He had characters as varied as the Old Woman in the Shoe to the Mayor of Hamelin.

Of course, you couldn’t blame Mel Blanc for being in a “aggressive or hectoring” way toward his fellow voice over artists – which we now know was totally false and a outright lie.

You have to remember that both Mel and fellow VO artist Paul Frees were the top two VOs in the animated industry back in the Golden Age of Animation and even shared the VO duties of “Flattop” in UPA’s The Dick Tracy Show while impersonating actor Peter Lorre.

And Mel Blanc was the one who paved the way in having the VO artists getting credits on the animated shorts and movies. Back then you couldn’t tell who the actors were in cartoons unless you recognized the voices.

Here’s a partial list of many of Mel Blanc “uncredited” work in other animation studios that he worked for in the Golden Age, other than Warner Bros.:

• Universal Studios for Walter Lantz Production as the original voice of Woody Woodpecker and various other voices

• MGM (Peace on Earth, The Lonesome Stranger, The Little Mole and in The Captian and the Kids and the short lived Count Screwloose series – among much else)

• Columbia/Screen Gems (various voices – including the Fox and the Crow in The Fox and The Grapes)

Since you brought up Frees, he also worked at WB, in their last theatrical production, “The Incredible Mister Limpet” as Don Knotts’s best friend (or bestie or BFF as the kids say today), the quite irritable “Crusty the Crab”, with the Snuffy Smith voice and temper…esp.when called Crusty since Mr.Limpet himself picked the name (Elizabeth MacRae was the voice for Limpet’s main squeeze, Ladyfish, the female dolphin to Limpoet’s mal;e–squeeze, hey–she’s not an octopus..)

Great post, Keith!

Blanc was a fascinating personality and, yes, too often he fell back on standard familiar “publicity” sound bites when giving interviews. I remember being frustrated trying to get something new and different out of him but by then he actually believed those things he was telling reporters like me. Like most people, I grew up thinking that Mel Blanc did every cartoon voice. Clarence Nash once told me that people thought Blanc did the voice of Donald Duck.

I second, third and fourth the recommendation that Keith Scott should write a book about the history of voice actors in cartoons.

Actually, Walt claimed that he didn’t want to publicize a voice for a character (although he sometimes did like at least one 1938 magazine article showing the Seven Dwarfs and multiple photos of the actors who portrayed them) because he felt that the voice was only one part of the character, that the animation and writing helped shape the character as well. However, I do concede that Walt disliked giving any recognition to anyone at all because he grew up at a time where people would steal talent from him, not just Iwerks but Bert Gillette and Dave Hand among others.

Here’s an Animation Anecdote for you: . Actor Walter Matthau was Mel Blanc’s next door neighbor for twenty years. At Blanc’s Memorial Service, Matthau spoke and his remarks were published in Daily Variety for August 10, 1989:

Mel Blanc was originally going to be the voice of Dopey in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs but Disney decided to have Dopey being mute.

Tremendous article Keith.

I guess it’s understandable if Blanc’s own fanciful recalling of events would draw criticism, but I never bought the notion he was trying to marginalize other voice actors. Nothing to gain there, as he was THE definitive voice man.

I was fortunate to see Mel in a personal appearance in the mid-late 60s. He was a featured attraction at a boat-and-travel expo in Omaha. Even I thought it was an odd bill, and wondered who in that crowd would know or care. As it turned out, the normal traffic at that show quadrupled, and thousands gathered at the stage. By that time, WB toons had aired every day for years, and Mel was a known player.

He went through his routine for a good half hour, telling funny stories and doing virtually every character in the stable.

Crowd. Went. Crazy.

Don’t forget that Charles Irving (as narrator) did receive screen credit on Famous Studios’ Kartune and Screen Songs cartoons.

I’ve been reading about Keith’s book for about fifteen years online..still waiting for it as well..

Mel’s shareing WB credit with others was like this:

First, the shared credits where Mel would be listed, above the musical director of the day (by that time, Milt Franklyn and later Bill lava), then the other actor below in smaller fonts as mentioend

mid 1960s the list of credits same way (still what was done since mid 1950s), in the “magazine masthead” format–THEN AFTTER that Mel’s credit on one card.

Then in the 1967-69 era, three cases of shared credit

Paul (Dave) Dixon and Paul Stookey for Norman Normal

and the final “series’, Bunny and Claude, Mel Blanc and pat Woodel (though it was in the other order.. Only the final B&C cartoon had Mel on one card as in the mid 60s and Pat Woodel (and vocalist/songwriter(?) Billy Stange) and a seperate card.)

Wonderful and insightful read. I absolutely love learning about the behind-the-scenes dates and production details.

But the one thing I was pleasantly surprised to see was the mention of Count Cutelli. A while back I was doing some research for my Bugs site, and I stumbled upon his various obituaries from July 1944 that claimed he was the voice of Porky. I had personally never heard of this man before that, so I was curious as to who he was and what (if any) his connection to the studio was. Thank you for shedding a bit of light.

Very good point…I read Keith’s reference to Count Cutelli earlier this morning when seeing this…But Blanc, of course, already was there when the That’s All Folks stuttering phrase as Porky Pig was done….

Great article! Quick question, what was the story with Bernice Hanson? And now I understand her actual name was Berneice Hansel?

Hansel? HAN-sel? Han-SEL?

Thank you for this astonishing work and dispelling some common misconceptions, Keith!

This article needs be published on the mainstream media right now.

Now of course you have name actors getting paid buckets of money to do feature film work that a voice specialist could have done better. The tail wags the dog, and the public goes, “oh, Tom Hanks was so adequate as Woody!”, but no one can name a single animator or character designer.

See what ya did, Mel?

Adequate? Tom Hanks did a fantastic job as Woody, and Tim Allen did likewise for Buzz Lightyear. I don’t think dedicated VAs could have done either of them better, although they probably wouldn’t have done them worse either. But you can’t watch the “BUZZ LOOK AN ALIEN” scene and tell me there was no magic.

The problem was Dreamworks saw this and thought hiring celebrities as VAs was the cool thing to do, and they made lame choices like Jack Black and Jerry Seinfeld. So if you ask me, Hanks and Allen did too good a job, because they gave producers the wrong idea about casting these kinds of roles.

Just the way the system works I guess.

If this is a specimen of what we’d get from a book, please: (a) alert me when the Kickstarter commences, and (b) take my money. For that matter, we desperately need a new B&F edition.

I do recall, I think it was a Mike Barrier interview, that there was something bizarre about the short career of George Hill at WB.

Thank you, Keith, for your insightful post.

As has been stated here countless times, no one back in our animation’s golden age, as we’re constantly calling it, ever expected that there would be a day when we could so neatly privately and obsessively examine all kinds of great films and short subjects for background information. Folks like Mel Blanc probably never figured that they would see fame and recognition beyond their days as voice artists on radio and TV and theatrical films.

So, obviously, he and so many other greats naturally forgot a lot of their own colorful history as records were lost by studios who figured that no one would care. But, hey, we do, and even now, with so much backlash from the studios, I can’t just let go of all this amazing stuff and still hold out dimming hopes that more and more great animation is restored fully so we can see credits and learn more about this history. I wonder how many of the animators expected that there would be worldwide recognition of what they do, right down to the rarest frame, but I declare again and again, that this is a unique and amazing art form that, all too often, has been overpowered by other media or has been shunted in the background as being “kid stuff”.

I don’t suppose that kids of today even care about animation the way I did (and still do, in my way). Voice artists like Mel honed their characters so methodically that there is real life blood flowing through them. In his MGM cartoons, there were times when he even proved himself a decent dramatic actor as well. In a way, the part of a simple cartoon like “THE HUNGRY WOLF” in which the wolf suddenly goes mad with hunger, fighting between suddenly confronting a kind of emotional tie to the rabbit that he once only thought of as dinner after the rabbit was going to “accept” him as surrogate “daddy” is really quite amazing. The performances lift this cartoon out of the duldrums of the usual kid fare and make us believe in the situation, and Harman must have seen that as well.

Of course, I’m sure that, mostly, Mel enjoyed nothing more than using his voices to make people laugh. It even got him on “THE TONIGHT SHOW” more than once, even one time appearing with Jack Benny to perform one of their typical old radio exchanges. Keith, I’m sure that book on the history of voice over talent will be amazing and, yes, it would be fun if books like this were multimedia. After all, those clueless folks who just casually pick up such a book and wonder what all the hoopla is about should have a sample of that great art of voicing on a CD or DVD/Blu-ray. It’s worth the effort, especially after we got a chance to hear some of the rare session work on the original “BULLWINKLE SHOW”.

Great article about Mel. I also liked the mention of my good friend Dal McKennon. I loved your book The Moose That Roared. I am eagerly awaiting your new book on cartoon voices.

A B&W print of “The Mouse-Merized Cat” with original titles turned up on eBay in 2010. But I don’t know whether it ended up “in the right hands”.

http://toolooney.blogspot.com/2010/09/tale-of-two-mice-original-titles.html

I never really noticed before that Mel’s name was originally only on Bugs cartoons. Although i’m sure other shorts with Blue Ribbon titles didn’t help.

Bravo!

Though this article certainly strives to be fair, it does seem to be something of a whitewash job on Mel Blanc. Because of his voice credit on the Warner cartoons, and his appearances on radio, (yes, radio was for the ears only, but he was extensively featured in radio magazines — similar to movie fan magazines– and publicity material with Benny and others) he was the only cartoon “voice” the moviegoing public knew by name.

It’s just human nature, though maybe not the best part of it, to take advantage of a situation. Mel Blanc was both the voice and “face” of Warner Bros. cartoons, and by his contract, only his name appeared on screen. The only cartoons on which his credit did not appear were those in which he played no part at all; like most of the Road Runners and minor series like the Honey-Mousers.

When Mel was starting out and working for every cartoon studio in Hollywood, he was just another “working stiff” radio actor.

Warners made him the “indispensible man.” They could have continued to make cartoons and keep their characters going without Friz Freleng, Chuck Jones, Robert McKimson, or any of the others; but not without Mel Blanc, and he knew it. If Mel did become an ego-driven monster, he was a Frankenstein of Warner’s own creation. No other studio ever relied so heavily on one actor for their character voices.

As for Mr. Arthur Q. Bryan, he was also extensively heard on radio as “Doc” Gamble on Fibber McGee and Molly, Floyd the barber (somewhat similar to Howard McNear’s later character on TV’s Andy Griffith Show) on The Great Gildersleeve, Elmer Fuddish characters like “Raymond Radcliffe” and “Lucius Llewellyn” (insert W’s…) on other comedy shows, and a year or two as Detective Lieutenant Walter Levinson on Richard Diamond, Private Detective with Dick Powell. He also appeared extensively on camera in movie character roles, including the newspaper editor in The Devil Bat with Bela Lugosi.

Having known and crossed paths with Keith for years, we both agreed on two things: 1) that Mel Blanc was the best actor to ever voice cartoons, and 2) the Warner cartoons and characters would’ve never achieved their popularity or classic status without him.

I actually think this even-handed article gives Blanc a break in some respects because it absolves him of sins he had nothing to do with. Until Keith clarified it for me ages ago, I, like many others, thought Blanc’s contract prohibited Bryan, Benaderet, Berner, Freberg, Bletcher, etc. from getting screen credit, when that just wasn’t true. A cartoon voice credit was just an anomaly for decades in general. Blanc’s “showbiz” tales do get a little grating, considering that even to this day asshats maintain Bugs was really named “Happy Rabbit” because of some B.S. Blanc told in his book, and use that as justification to fill Wikipedia with misinformation. I’m thrilled this article now exists, simply because the facts are now on public record.

Maybe it all did go to Mel Blanc’s head – just like it did with other key Warner figures, Chuck Jones and (yeah, I’ll say it) Bob Clampett especially. But as we all know, it wasn’t like it was without just cause. And if those guys did think they deserved more recognition and money (really, Blanc collecting $125 a week at the end of the ’40s was the bargain of the century) for the culture they created – well, they were right.

I would counter-argue that Daws Butler, while maybe not quite Mel Blanc’s equal in vocal range, was the best ACTOR among cartoon voices. He could and did play a wider range of emotions, and could add genuine tenderness to a character (maybe more notable in his records with Stan Freberg than in his cartoons.) All Warner characters are pretty much the same, that is, smartasses; Mel was terrific at that but sounded horribly phony trying to play it any other way (i.e. the grandfather mouse in Hugh Harman’s “Peace On Earth.”) Paul Frees always seemed aware of playing his voice like an instrument, much the same as Harry Shearer today.

No argument from me that Daws could do things Mel couldn’t (so could Stan in some respects). But when I talk acting, I mean the real kind of passion that had no parallel in animation at the time, and really hasn’t sense, that helped the Warner cartoons transcend beyond anything the other studios were capable of (especially in Mel’s work for Clampett and Freleng). Daws unfortunately arrived too late to the party and didn’t get that opportunity too often, but in an alternate universe, could he have filled Mel’s shoes? Obviously, yes.

Jeff, very acurrate point about Blanc playing (I hate to say only smartasses.)

Here’s some other male actors from the era who DID play not only other types

but other types of story (I.e., “Father Knows Best/Adrich Family” type gentle comedy, fairy tales,

murder tales, romance,etc.,etc.,etc.and the King and I)

Marvin Miller

Don Messick

Hal Smith

Dal McKennon

Paul Frees (though his natural voice, as heard thru Disneyland parks is just as famous)

Shepard Menken (though he’s best-remembered through that dead-on Richard Haydn voice as in the Chipmunks’s Clyde Crashcup)

But another important “for-what-it’s-worth”-even today’s no-name voice artists annoy my hears through and through, and the cartoons aren’t that much better. “Rugrats”, the latest Cartoon Network shows like this Gumball (referencing the ads I’ve heard in movie theatrees, WHAT IS WITH THIS SCREAMING with different scenes of the latest Cool-TOONS–term I invented….)..which are the ONLY cartoon voices outside of famed names getting mentioned.

These upper points are related because I get a very different feeling with 1940s-60s films,with radio-experienced actors playing them (yeah, a familiar bias on my part there, but it’s true,given the vocal reliance..) aside from the celeb-no-name thing..Dinah Shore and others, who’d bene on radio, did Disney films an d it trned out well. In short regarding what I mentions in my above paragraph, unless it’;s the current hot cartoon on TV, no voice artists get much mentioned, certainly no one from the cartoons Blanc worked in, especially the people that only Leonard Maltin (“The Disney Films”), Jerry Beck and Will Friedwald (“The Warner Bros.Cartoons” & “Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies”_), and Keith Scott himself and others mentioned.

I mention, how many people know of Walt Disney’s twist on the Reluctant Dragon (1941)’s voice besides us researchers/fans (Barnett Parker,btw), Ginny Tyler Julie Bennet or narrator Bob Bruce, for instance.

In a nutshell—-there were all kinds of emotions for actors to go but as for Mel Blanc, his ties to the smartass WB studio contractuially,though not being his ticket to onscreen credits, were what kept him from doing more kinds of cartoons altogether (like that MGM Wolf cartoon Kevin Wollenweber mentioned, and I’ve seen it too) and we may be S.O.L. hoping anyone real cartoon voices excepting the kids’s television favorites today get mentioned. Even Mel Blanc slowly seems to be fading..and then only mentioned in some quarters for Captain Caveman…NO Daffy or Bugs this H-B character

By thge way, Keith, “Tedd Piere as narrator”(1936’s Village Smithy)? I always thought it was Earle Hodgins… otherwise very good article. Also, the “S” was added to “:Voice characterization” in Hare Spilitter (#1059). Ironcially, the very first non-star series to have the Blanc credit (though with the “Duffy’s Tavern” cat the credit was’t for nothing) 1945’s Hush my Mouse was Sniffles’s and the Porky in a Drum ending’s farewells.

BTW some cartoons using Mel’s credit but not featuring him were the Three Bears shorts except

their farewell “A Bear for Punishment” (1951) and I THINK “What’s Brewin’ Bruin” (1948)…

Only their debut, and the early voice-credit short, “Bugs Bunny/Three Bears”, warranted Mel’s credit, since the famed name of the first two words of the title is in it. (Odd how this and the only previous WB cartoon giving Mel screen credit, “Little Red Riding Rabbit”, were send-ups of fairy tales; so were the two Bugs’s that Jim Backus appeared in, in the late 40s for Bob McKimson, “A Lad in his Lamp”, as Smokey, and “Wind-Blown hare” – even though Jim’s only heard in the short for less than a minute, as the wolf, and Mel himself takes over, also playing the pigs – though Bea Benaderet also does a cameo, as Granny-as in Little Red Riding Hood’s Granny.)

Ironic how Mel was Papa Bear in the first 3 Bears Jones short before the Wolf in the Riding Hood Freleng one, Billy Bletcher took over in 1947-48 in “What’s Brewin’ Bruin” and the next three.”(Stan Freberg took over Kent Rogers as Bab but Bea Bendaderet, aka Red from “Riding Rabbit” always held the Mama Bear role from day one!).

I thought Jackson Beck was credited for at least one “Screen Song”. I could’ve sworn I saw his name for the one about Switzerland.

Yes, it’s “The Ski’s the Limit”.

Considering that Stan Freberg, Chuck Jones, and June Foray were actually there when this was happening tends to make me think they knew what they were talking about in regard to Mel Blanc and the credits controversy. Revisionist 2016 whitewashing articles? Not so much.

Ah, yes. “The hell with that paperwork! What good are facts!?” The old “revisionist” label. While people like you use it to decry someone, what you really mean is that Keith has set the record straight and written the story behind Mel Blanc’s screen credits the way it should’ve been written in the first place – accurately. While it angers me that armchair experts who’ve never done any sort of research can dismiss years of hard work in a single blow, it delights me that most of the readers see Keith’s work for what it is: a thoroughly illuminating and entertaining piece backed up by a mile’s worth of documentation. But yeah, forget all of that, and just listen to the other “showbiz” tales of Chuck and Stan – when were they ever proven inaccurate?

Love this article. I came out of it with a greater appreciation of Mel and other voice actors.

So basically, it was sheer luck and having been at the right place and time for Mel to have gotten that written into his contract? To say that he “earned it” might be a more fitting answer as any, than less an under/overstatement.

I’ll digress about the quality of this article (others have more than covered the gratitude the majority of us feel for it), and just mention how my jaw dropped at seeing not just title slates for ‘Tweetie Pie” and “Mouse Menace” but slates that are stated to be from original negatives? Are those Technicolor negatives?

The film purist in me jumps for joy at seeing such material and knowing it is in proper custodial hands!

They’re from the B/W TV negatives struck in 1956, and have the Technicolor slate blocked out (by a weird brick wall pattern). I myself have seen or owned pre-Blue Ribbon prints of several Warner cartoons, including “Tweetie Pie”.

Thank you for the clarification, Thad. Still wonderful to see.

They’re from the B/W TV negatives struck in 1956, and have the Technicolor slate blocked out (by a weird brick wall pattern).

That did came off pretty weird how they did that. I suppose going with a black matte like what NTA did wasn’t in their best interest, though at least it’s a step up from the black marker on every frame that MGM used for their Technicolor censoring.

I believe “Tweetie Pie” was originally made in Cinecolor rather than Technicolor. The “Blue Ribbon” titles carry the phrase “Prints by Technicolor,” rather than “In” or “Color by” Technicolor. I used to have a b/w 8mm home movie edition that included the “brick wall” as part of the main titles. The out of sync opening on most of the AAP TV prints appears to have been caused by using the picture element from the “Blue Ribbon” version with the sound track from the original release version, and “syncing them up” tails out (in lab slang, starting from the LAST frame of each.)

For an extreme demonstration of the versatility of radio actors and actresses, I’d like to recommend listening to the “Quiet, Please” horror episode “The Thing On The Fourble Board.” The “voice” of the inhuman, snarling monstrosity that emerges from deep in the earth by way of the drilling pipe of an oil well was performed by Cecil Roy…the same actress who played LITTLE LULU!

In the 40s-50s, Blanc was just working. His virtuoso work at Warners is what he’s best remembered for now, but in the “golden age” of radio being a featured supporting player on Jack Benny, Judy Canova, Burns & Allen and Abbott & Costello was a big deal. Radio passed, the cartoons didn’t. He got 1st class screen credit at WB; that must have been satisfying, but perhaps not uppermost on his mind.

Whoops, I note a mistake I made…in 1936 Ted Pierce actually narrated Porky the Rain-Maker (not The Village Smithy, which was narrated by screen & radio actor Earle Hodgins). Porky the Rain-Maker was the first cartoon with an off-screen opening voice, although Tex Avery mis-remembered the first time he used voice-over as being Village Smithy, and I guess I did too! Sorry about the inaccuracy. I see SCarras picked up on that point in the Feedback. Avery and Clampett also used Hodgins in his patented screen role of the snake oil salesman.

I’m happy the article generated a flurry of interest and some differing opinions, but I don’t think it’s (as “Fred” said) “revisionist” – rather it’s based on several research trips to USC and a fair bit of listening to soundtracks and radio for forty years. I would call some of Mel’s PR stories revisionist, along with some anecdotes by June Foray, Stan Freberg and Chuck Jones. Each of them were compelled to repeat certain stories so often they came to believe them, as Jim Korkis said. I found Freleng for one was much more accurate about facts. But each to their own opinions…I love the work of Blanc equally with the work of Frees, Butler and others.

Thanks a lot, Mr.,Scott (rhymes, like an early Hanna-Barbera cartoon!) I did find the Freberg gripe about Blanc’s credit in the “{Cool and Strange magazine:, in 1998, and also, Ted Pierce DID, for to my memory, the first time, do that sore throat voice known to many, for the blacksmith (“Porky the Wrestler”‘s Champ, “Hold the Lion’s” and “From Hand to Mouse” lion, “A Hare grows in Manhattan”‘s bulldog, and “Birth of a Notion”‘s Leopold the dog all have that voice, among others, can’t think of any of the “post-1948” cartoons,that were ACTUALLY part of the package (no retraced black and whites with jumping “oo”‘s in cartoon that began with “Now Hear This”,1963), the ones released after Marvin the Martian’s debut “Haredevil Hare”, that used that Pierce “Blacksmith voice”. Was it still used thru the early 2950s? Ironically though Pierce ocassioanlly still was heard..

Without trying to stir up the hornet’s nest further, I’m pretty sure I’ve read accounts of Mel Blanc’s rudeness to fellow actors, in particular younger, less-experienced players, in interviews with Jean Vander Pyl and others who worked with him in later years at Hanna-Barbera. I’ve also heard outtakes of solo recording sessions, probably made in his own studio, where his banter with the engineer implied that he just wanted to record the lines in a hurry and get the hell out. In these sessions, he seemed to be directing himself or with the help of said engineer.

Wow. Very extensive and insightful work. I’ve read Mel’s autobiography myself and noticed several other contradictions; like him claiming that he voiced Bamm-Bamm on The Flintstones (instead of Don Messick) and did the Road Runner’s “Beep, Beep!” line (instead of Paul Julian); or that both Bugs’ name and “What’s Up, Doc?” line were his ideas (instead of Tex Avery’s and the others who helped develop Bugs); or as you said when exactly he was signed to WB’s exclusive contract. I’ve just assumed that since his autobio was published just a year before Mel died at 81, that most of these contradictory claims he made in the book were the result of memory loss. That quote about him being “the worst cartoon historian” seems to back that up. Anyway, thanks for the extra insight on Mel. Though he died the year before I was born (1990), I still grew up on his voice work thanks to Cartoon Network and am still a big fan to this day.

This post really makes me want to read a book about voice actors written by Keith Scott.There were a handful of cartoons that carry no voice actor credit. Road Runners, of course, which were not voiced by anyone, and several others that used guest voices. Daws Butler got a credit for one of the Army cartoons in the mid 50’s (90 Day Wondering maybe?), and maybe one or two travelogue spoofs that used Robert C. Bruce.

Great piece of research and writing and I enjoyed it immensely. If you can do this fine an article on one facet of the subject matter, I can’t wait to see what you could do with a whole book.

The original titles for “Of Thee I Sting” have been found and indeed Blanc is not credited.