Fewer people attended picture shows at theaters after the 1940s, and the decline in attendance devastated the market for short animated cartoons. The new medium of television drew people away from the movies, and fewer ticket sales meant less money for film distributors to financially support their animation studios. Movie ticket prices for shows with cartoons were the same as those without cartoons, and theater managers balked at rising rental costs for cartoons. As theaters discontinued booking cartoons, animation studios struggled in vain to stay open amid rising production costs and declining revenue.

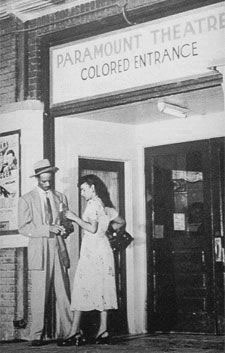

On the other hand, by the mid-1960s television was not the only cause of dwindling movie audiences. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed segregation in public and private businesses. The Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board had already prohibited segregation of public schools ten years earlier, but many communities still refused to comply as of July 2, 1964. As a result, the new civil rights law forced theaters to allow children of different colors to sit together in a dark auditorium to watch films in many communities that still resisted sending children to well-lit, desegregated schools. Parents immediately stopped sending their children to the theaters on Saturday mornings.

On the other hand, by the mid-1960s television was not the only cause of dwindling movie audiences. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed segregation in public and private businesses. The Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board had already prohibited segregation of public schools ten years earlier, but many communities still refused to comply as of July 2, 1964. As a result, the new civil rights law forced theaters to allow children of different colors to sit together in a dark auditorium to watch films in many communities that still resisted sending children to well-lit, desegregated schools. Parents immediately stopped sending their children to the theaters on Saturday mornings.

Before 1964, some movie houses foreshadowed the exodus of European American children from the matinees. The Forest Theater opened as a “whites only” venue in South Dallas, Texas in 1949 and held weekend matinees and holiday-themed cartoon marathons. African Americans moved into the suburb, and “white flight” led Forest’s management to convert the place into a “colored only” theater in 1956. In so doing, it stopped offering special cartoon shows and largely played second-run movies. Richmond, Virginia voluntarily desegregated its theaters in 1963, and an immediate backlash ensued. One teenager wrote to the local newspaper to vent her frustration. “If the management wants the colored business more than the white business, let them have it,” she declared in the Richmond Times Dispatch of June 19, 1963.

And then there was Greensboro, North Carolina. The city’s Carolina Theater had hosted a weekend matinee and talent show for children called Circle K. The Carolina was a segregated facility until 1964, and African American children were restricted to the balcony. Manager Neil McGill later told “Greensboro Voices/ Greensboro Public Library Oral History Project” that “the attendance fell off” after integration. He blamed desegregation for the decline in European American attendance, and he cited “misbehavior on the part of blacks” at the Circle K for driving European Americans away from the Carolina. The theater discontinued the Circle K in 1967.

And then there was Greensboro, North Carolina. The city’s Carolina Theater had hosted a weekend matinee and talent show for children called Circle K. The Carolina was a segregated facility until 1964, and African American children were restricted to the balcony. Manager Neil McGill later told “Greensboro Voices/ Greensboro Public Library Oral History Project” that “the attendance fell off” after integration. He blamed desegregation for the decline in European American attendance, and he cited “misbehavior on the part of blacks” at the Circle K for driving European Americans away from the Carolina. The theater discontinued the Circle K in 1967.

That same year the Loew’s theater chain ended its Saturday morning matinees, and the shorts market continued to evaporate. As a result, the closings of cartoon-short studios accelerated in the late 1960s, with Paramount/Famous in 1967, Warner Brothers in 1969, and finally both Terrytoons and Walter Lantz in 1972. Moreover, the cancellation of matinees in the South because of “white flight” suggested that managers considered cartoons as films for only European Americans to enjoy. Perhaps distributors did, too. Warner Brothers refused to release any new cartoons with the flagship character Bugs Bunny after 1964; in fact, the final episode False Hare was released exactly two weeks after the Civil Rights Act went into effect.

Meanwhile, DePatie-Freleng’s Pink Panther was the only animated-short star with considerable longevity to have emerged after the Civil Rights Act, albeit by only a few months (December 1964). So, ironically, African Americans became a larger demographic in Saturday matinee attendance when a character defined by his color was the major draw.

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

This is a very interesting post, and it is indeed sad to know that desegregation is considered the “cause” of, say, the Saturday matinee, something that I truly wish would come back again, with showings of older cartoons or, hey, new animation aimed at family audiences; yeah, I know times are changed so much between those days and modern days, but I miss those kinds of venues.

But thank you for this jarring bit of history; we all should know more about this, along with the fact that animation, itself, has a long, long history. It is also interesting to note that Bugs Bunny’s last golden age cartoon came in 1964, proving the wabbit lived through our trying times and, yes, the gag content carried over, in some cases, to the PINK PANTHER series.

I suspect suburbia — itself partly fueled by white flight — and the decline of neighborhood movie houses as genuine neighborhood attractions had something to do with it as well. If the kids were primarily local, management could spot and ban regular brats, and perhaps even notify parents. If parents a few zip codes away are dropping them off at a multiplex or mall theater, it becomes What Happens At Matinee Stays At Matinee … and kids know it.

The death of theatrical cartoon was mirrored by the death of the cheap kid-friendly genre picture. Just as animation talent ended up doing faster and cheaper at HB, live action talent ended up cranking out television series that were faster and cheaper versions of the Bs and serials they were doing before. There were still new B movies to be sure, but the kind preferred for matinees were not available in the quantity and at the price necessary.

Also, the 60s saw Saturday morning established as the slot for kid shows, eventually all cartoon shows. That was a major nail in the coffin for Saturdays at the movie house.

It’s kinda sad in a way since I sorta see how towns like my were ruined because people did not have the open minds to accept this new trend and simply fled with their troubles further out into the ‘burbs without looking back. We learned a sad lesson from the days before segregation was abolished, bu obviously a history that had to happen sooner or later.

I mean to point out that there were animated films that daringly (for its time) dealt with the changing faces of movie-goers in the age of desegregation. To my mind (and please feel free to jump in here and correct me), the pioneers in this end of the history of animation is or should be John and Faith Hubley and their thoughtful takes on how the races looked at each other and how we, as a human race, ought to start fully communicating. These films also utilized jazz and experimental musical scores and graphics that were vastly different than anything we saw in animation’s first golden age. There are examples of these wonderful films if you look around on the internet.

Indeed, the Hubleys are pioneers of the post-Jim Crow era. Even during legal segregation, however, some independent animators tackled the problem. UPA’s BROTHERHOOD OF MAN is perhaps the best-known example, but Philip Stapp animated anti-segregation films in the 1940s that made their way to public libraries and YWCA branches in the South. His BOUNDARY LINES is an especially powerful film.

Also, thank you for the compliments. I have only seen the shorts as tv reruns, so I can only imagine the matinee experience. Many African Americans of the era told me that either they did not go to matinees offering balcony seats or their parents did not let them go. Instead, they’d just go to the “colored theater” to see a second-run cartoon with a feature, but the theater would not necessarily have a cartoon matinee.

There were a few small producers that turned out B movies with black casts for segregated theaters. TCM occasionally airs some. Think I asked before, but did anybody ever venture commercial animated shorts for a black audience?

I’ve always been curious who made the decision at Warner Bros. post-1964 (when theoretically DePatie-Freleng had access to the entire stable of Warner characters) to only do Road Runner/Wile E. Coyote, and Daffy Duck/Speedy Gonzales cartoons. Granted, considering how horrible the animation quality became by then, in some ways it’s perhaps a blessing that they didn’t use Bugs Bunny, Foghorn Leghorn, etc., but it always struck me as very odd that they wouldn’t use Warner’s star character, Bugs, at all. I would have thought the studio would have insisted on it.

While we don’t know who exactly made the decision to only produce Road Runners, Daffy and Speedy cartoons in the mid-1960s, it was a conscious decision made by Warner Bros. – both because they had plenty of Bugs Bunny cartoons which they kept in active theatrical reissue during the 1960s, and because they were prepping for the eventual Road Runner Show and a possible Daffy Duck and/or Speedy Gonzales series for Saturday morning.

Sad if that’s what did in these theaters of old.

Woudln’t surprise me if Hollywood still hadn’t quite got the memo for a long time given the circumstances.

Wow! I never thought of it like that.

Sort of along these same lines is this 1955 animated film commissioned by the American Council To Improve Our Neighborhoods, called “Man Of Action”.

https://youtu.be/RUmECXiB_RU

Excellent film to highlight here. Always weird going back to this one thinking had not the future event occurred, that guy could’ve easily been sent to the slammer for that false information! The Devil certainly didn’t plan ahead there!

I think it all had a lot more to do with Television. Bugs Bunny theatricals ending after the Civil Rights Act was probably just a coincidence. In Brookline, MA, we still had all-cartoon matinees in the 70s.