It’s the first of “All-Warners Wednesday” which means we breakdown a Looney Tunes or Merrie Melodies short each Wednesday this month. Today’s initial installment presents the debut of the Tasmanian Devil!

As Warner Bros.’ animation department searched for a new adversary for Bugs Bunny in the early ‘50s, director Bob McKimson believed they used up every conceivable animal character, except a Tasmanian Devil. His writer, Sid Marcus, didn’t have knowledge of the creature but McKimson’s love of crossword puzzles gave him inspiration. In reality, the Tasmanian devil is a carnivorous marsupial—the largest of its kind—known for its intensity when feeding. McKimson designed the creature as a small, unruly monster with a gargantuan appetite. Upon his first entrance (animated by Phil De Lara), he spins like a whirlwind and is able to split a boulder in two, cut through trees and burrow himself into the ground and resurface again to a standing position, hunting for his next prey.

No records exist as to when the dialogue track or orchestral score occurred for Devil May Hare. It’s probable the dialogue sessions with Mel Blanc were recorded between October and November 1952; this film was in production in between Jones’ Bewitched Bunny (1954) and Freleng’s Lumber Jerks (1955) — Bea Benaderet recorded her lines in October for Jones, and Stan Freberg voiced for Freleng in November. Around this period — shortly after UPA’s Gerald McBoing Boing won an Academy Award — the Warners cartoons were influenced by the studio’s modern, geometrical method in their backgrounds, with layouts by Bob Givens and backgrounds by Richard H. Thomas. Bugs and the Tasmanian Devil are full and dimensional, but the foliage in the backgrounds is painted as abstract stylizations with leaves mere lines in their representative colors, or in some cases, drawn lines with no filled color.

No records exist as to when the dialogue track or orchestral score occurred for Devil May Hare. It’s probable the dialogue sessions with Mel Blanc were recorded between October and November 1952; this film was in production in between Jones’ Bewitched Bunny (1954) and Freleng’s Lumber Jerks (1955) — Bea Benaderet recorded her lines in October for Jones, and Stan Freberg voiced for Freleng in November. Around this period — shortly after UPA’s Gerald McBoing Boing won an Academy Award — the Warners cartoons were influenced by the studio’s modern, geometrical method in their backgrounds, with layouts by Bob Givens and backgrounds by Richard H. Thomas. Bugs and the Tasmanian Devil are full and dimensional, but the foliage in the backgrounds is painted as abstract stylizations with leaves mere lines in their representative colors, or in some cases, drawn lines with no filled color.

Devil May Hare was one of the last cartoons animated by the four principal animators in McKimson’s unit of animators before the studio shut down its animation department in 1953. Charles McKimson and Phil De Lara left Warners to work on comic books for Western Publishing. Herman Cohen left for Walter Lantz, and Rod Scribner moved to UPA. Their migration took an effect on McKimson’s cartoons after the studio reopened (beginning with Weasel Stop, released in 1956). The animation often couldn’t match the vitality of the earlier efforts, indicative that the new unit followed the director’s layouts precisely.

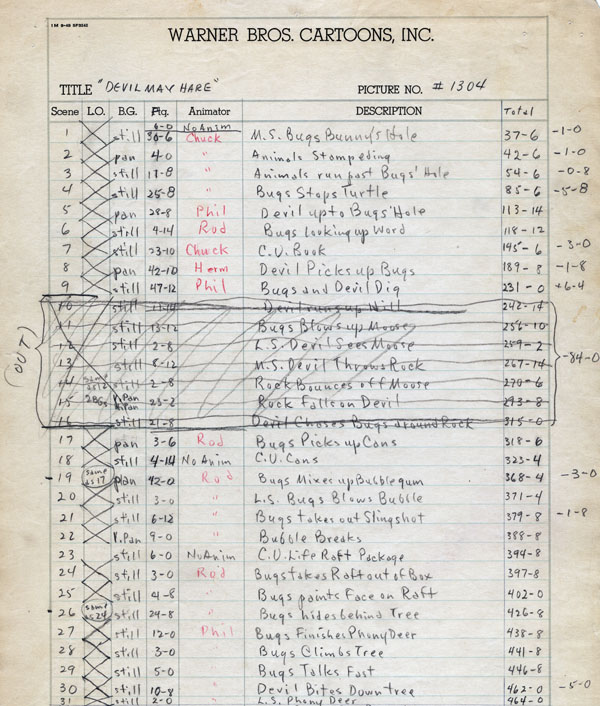

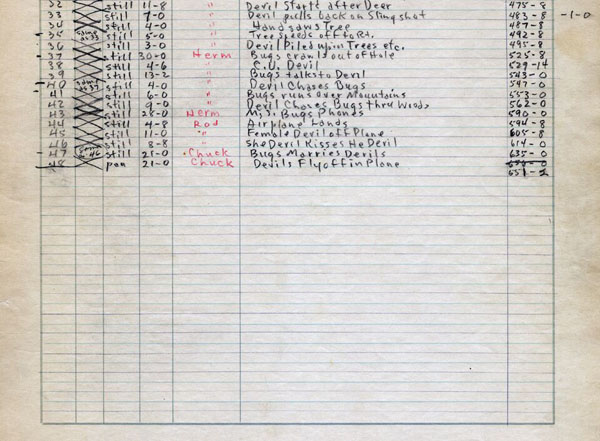

Charles McKimson isn’t assigned much footage in the film — he’s only credited for the opening scenes, with Bugs and the menagerie fleeing from the Tasmanian Devil, and the closing scenes where Bugs officiates the wedding between the Tasmanian Devil and the “lonely Lady-Devil,” dressed as a minister.

Charles McKimson isn’t assigned much footage in the film — he’s only credited for the opening scenes, with Bugs and the menagerie fleeing from the Tasmanian Devil, and the closing scenes where Bugs officiates the wedding between the Tasmanian Devil and the “lonely Lady-Devil,” dressed as a minister.

By comparison, Herman Cohen animates his scenes in a more flexible manner. In scene 43, even Bugs knows his ultimate scheme of seeking a female counterpart to marry the repulsive brute is twice as sickening. It’s telling in Bugs’ facial expressions as he quickly remarks to the audience before reaching the Tasmanian Post-Dispatch via telephone, “What I got up my sleeve shouldn’t happen.”

Phil De Lara and Rod Scribner animate their own sections that display the Tasmanian Devil’s voracious hunger. Scribner handles the sequence of Bugs melding a chicken with a mixture of liquid bubble gum and bicarbonate of soda (commonly known as baking soda). Before chewing—and suffering a hiccupping fit from—the fake poultry, the Devil scurries into the frame and whimpers like a restless dog. Scribner also animates Bugs using an inflatable raft to craft as a pig for the Devil’s next meal. De Lara animates the next sequences of Bugs preparing another course—a deer, with a barrel used for most of its body. The Devil is enraged by Bugs’ trickery and chases him up a tree. As Bugs tries to pacify him, the Devil takes large chomps from its trunk, lowering the tree with each bite.

After the cartoon was finished, producer Eddie Selzer felt the Tasmanian Devil was a violent, obnoxious character. He ordered McKimson not to make any more cartoons with the character, in the midst of production of another film. The reaction to the Tasmanian Devil was sensational; Jack Warner notified Selzer about numerous fan letters and demanded more appearances. Only four more cartoons (Bedevilled Rabbit, Ducking the Devil, Bill of Hare, and Dr. Devil and Mr. Hare) were produced with the Tasmanian Devil during the Warners theatrical era. He later became known as “Taz” (or “Taz Boy,” as some model sheets indicated). His popularity grew when the theatrical cartoons were shown on television, in addition to different merchandise sales. Taz played a bigger role with viewers when Warner Bros. Animation produced the animated show, Taz-Mania, which ran from 1991-95.

After the cartoon was finished, producer Eddie Selzer felt the Tasmanian Devil was a violent, obnoxious character. He ordered McKimson not to make any more cartoons with the character, in the midst of production of another film. The reaction to the Tasmanian Devil was sensational; Jack Warner notified Selzer about numerous fan letters and demanded more appearances. Only four more cartoons (Bedevilled Rabbit, Ducking the Devil, Bill of Hare, and Dr. Devil and Mr. Hare) were produced with the Tasmanian Devil during the Warners theatrical era. He later became known as “Taz” (or “Taz Boy,” as some model sheets indicated). His popularity grew when the theatrical cartoons were shown on television, in addition to different merchandise sales. Taz played a bigger role with viewers when Warner Bros. Animation produced the animated show, Taz-Mania, which ran from 1991-95.

The draft for Devil May Hare reveals in scenes 10-16—in brief, vague descriptions—a deleted section where Bugs inflates a fake moose for the Tasmanian Devil to devour. He throws a large rock at the moose, but it bounces off and crushes the Devil, which leads to a chase. If the scenes had been kept, it would seem unnecessary for the Devil to have an appetite for larger game after being duped into digging for groundhogs as an appetizer.

The finished cartoon has some slight sound editing goofs: the opening of Bugs humming “Tales from the Vienna Woods,” as he empties his vacuum cleaner, is out of sync. During the wedding ceremony between the Devil and She-Devil, the voices for the two are switched before Bugs pronounces them “Devil and Devilish.”

Enjoy!

(Thanks to Jerry Beck, Thad Komorowski, Keith Scott and Frank Young for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

This was also one of the first cartoons Milt Franklyn helmed solo as musical director, which you can tell in his choice of orchestration stylings (Franlkyn’s earliest efforts were more sedate and tried to get away from some of the fanfares Carl Stalling used. He changed after only a handful of shorts when it became clear why Stalling used them).

And ironically, the post-shutdown Carl Stalling scores sound noticeably different than his pre-shutdown scores. You get the feeling Stalling wanted to experiment with new styles. For one thing, Stalling used less famous song cues, and leaned more towards recurring original melodies. See “Hyde and Hare”, “The High and the Flighty” and “The Unexpected Pest” for probably the three best examples.

Stalling and Franklyn’s scores are harder to tell apart, post-shutdown, as both seemed to move a little in the other’s direction. The difference in the pre-shutdown scores — including some extremely subdued iris-out music by Franklyn — is very apparent.

I wonder if this was brought about over changes in music licensing. or the composers getting more of a royalty in using their songs in films?

Ah, the Tazmanian Devil; perhaps the second Warner Brothers character, along with the Road Runner, to be fantastically redesigned for cartoon license. I used to enjoy these cartoons just to watch the creature whirl through real estate devouring everything in his path, although sometimes, I wonder how the character would have played if he were created in the late 1930’s or the early 1940’s, when the full identity of Bugs Bunny was fully realized by Tex Avery.

The funniest part of Devil May Hare was the wedding of Taz and his bride with Bugs acting as the Justice of the Peace and first asks in a mixture of English and Gibberish (Ooo eee ooo ah ah which sounded like something out of Dave Seville’s Witch Doctor) to Taz which he responded “Uh Huh” and the same to his bride which responded “Uh huh” and Bugs said to both of them ” May I pronounce you Devil and Devilish as he escorted the newlyweds to the DC 3 waiting for them and said “All the World Loves a Lover. (Which was the name of a popular song that was preformed by Doris Day around that time)…but in that case we can make a exception!”

There’s a breakdown for AQUA DUCK up for auction on eBay at the moment:

http://www.ebay.com/itm/Warner-Bros-Orig-1964-Looney-Tunes-Bugs-Bunny-Cartoon-Directors-Lead-Sheet/272649534596?_trksid=p2047675.c100010.m2109&_trkparms=aid%3D555012%26algo%3DPW.MBE%26ao%3D2%26asc%3D40130%26meid%3De7925b7468a541e49a2eb2eb8387cf1c%26pid%3D100010%26rk%3D6%26rkt%3D6%26sd%3D252918198178

No matter whether the WB short was scored by either Carl Stalling or Milt Franklyn – just hearing the WB orchestra rise to the occasion to score a 7 minute cartoon is music to my ears!

WB toons (from 1936 to 1962) had the best music!

And I think it was in 1962 that Jack Warner fired his studio orchestra. Whether Warners had a few musicians on staff after that, or just hired freelancers on an ad hoc basis, I don’t know. William Lava’s first handful of scores, when he still had the orchestra at his disposal, weren’t that bad (his scores for the Joe McDoakes shorts were good), but the smaller combos did him no favors.

Interesting there is no uncredited animation by Keith Darling this time.