This column profiles animator/director Jack King, who worked at both Disney and Warner Brothers. Since King passed away before the Golden Age of animation was appreciated for its place in the industry starting in the late 1960s, many of the anecdotes related to him in this column are based on recollections from various colleagues.

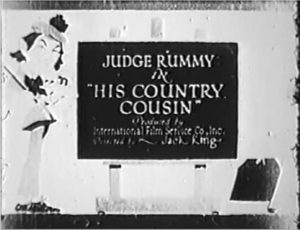

Born in 1895 as James Patton King in Birmingham, Alabama, Jack King relocated to New York by 1917, where he claimed to have started in the animation business at Raoul Barre’s studio. Later, he served as an animator for International Film Service, which produced cartoons based around popular newspaper characters owned by William Randolph Hearst. Copyright records indicate King is credited as a director—only in its earliest form, since he might have been the sole animator of these brief shorts—for cartoons starring Tad Dorgan’s Judge Rummy: His Country Cousin (1920), Kiss Me (1920), Why Change Your Husband (1920), and Too Much Pep (1921). Later, in the mid-1920s, he worked as an animator on Bill Nolan’s Krazy Kat cartoons at Nolan’s studio in Long Branch, New Jersey. (One of the Krazy Kats credited to Jack King, Scents and Nonsense, can been seen on the first Cartoon Roots volume, from Tom Stathes.)

Born in 1895 as James Patton King in Birmingham, Alabama, Jack King relocated to New York by 1917, where he claimed to have started in the animation business at Raoul Barre’s studio. Later, he served as an animator for International Film Service, which produced cartoons based around popular newspaper characters owned by William Randolph Hearst. Copyright records indicate King is credited as a director—only in its earliest form, since he might have been the sole animator of these brief shorts—for cartoons starring Tad Dorgan’s Judge Rummy: His Country Cousin (1920), Kiss Me (1920), Why Change Your Husband (1920), and Too Much Pep (1921). Later, in the mid-1920s, he worked as an animator on Bill Nolan’s Krazy Kat cartoons at Nolan’s studio in Long Branch, New Jersey. (One of the Krazy Kats credited to Jack King, Scents and Nonsense, can been seen on the first Cartoon Roots volume, from Tom Stathes.)

After Steamboat Willie proved groundbreaking in the advent of sound cartoons, Walt Disney looked to expand his studio with experienced animators from New York. Jack King re-located to the West Coast and was hired at the studio by June 17, 1929. Studio records indicate that King directed at least one cartoon for the studio during this period—the 1929 Mickey Mouse cartoon The Haunted House. As of this writing, there is no circumstantial evidence as to why King did not direct any other cartoons for the studio during the late 1920s and early 1930s.

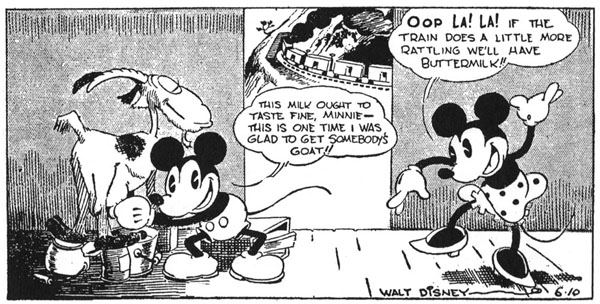

Besides serving as an animator on the Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphonies cartoons, King also filled in for the daily Mickey Mouse comic strip continuity for two weeks in the summer of 1930 (June 9 through June 21). In his animation and the Mickey strips, he tended to draw his characters with vertical pie-cut eyes. Another habit evident in King’s scenes of Mickey Mouse, as Wilfred Jackson (then a young animator) recalled, was that he drew hobnails on the bottom of Mickey’s shoes—much to Walt’s dislike. This practice became so frequent that the directors had to write notes in the animation drawings: “Inkers, do not ink hobnails on Mickey’s shoes.”

Jack King

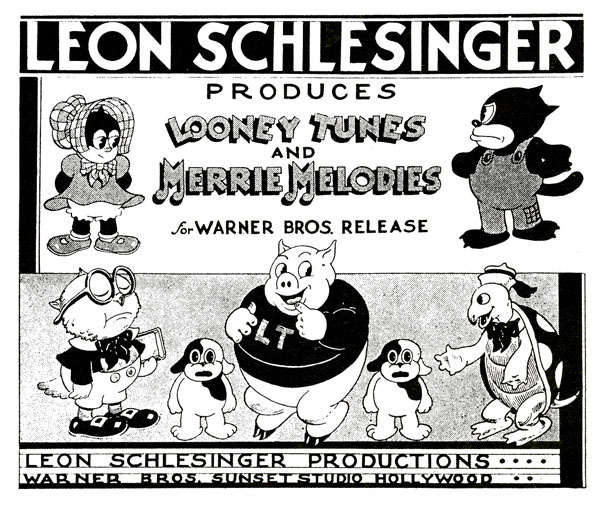

After Hugh Harman and Rudy Ising split with producer Leon Schlesinger in 1933, he established his own animation building on the Warners lot on Sunset Boulevard, raiding other studios for talented artists in the process. Jack King was one of the first outside animators hired at Warners, with a young Bob Clampett as his assistant. His new fellow staffers found King beneficial, given his experience in the industry. Clampett recalled shortly after the release of Three Little Pigs, King “told me much about the Disney style of distortion in the characters, the looser treatment on the pigs.” Phil Monroe, a young in-betweener hired in 1934, remembered the senior artist acting as an aide with a different type of animation: “Jack King was very big on effects; I remember he taught me how to do water, to make it look wet, rather than like a string of beads.”

King started as an animator at Warners, but soon became the principal director on the black-and-white Looney Tunes by 1934. He directed several cartoons with Buddy, such as Buddy the Detective (1934), Buddy’s Bug Hunt (1935) and Buddy the Gee Man (1935). After Friz Freleng debuted a series of animal characters in I Haven’t Got A Hat (1935), a take-off on Hal Roach’s Our Gang comedies that marked the debut of Porky Pig and Beans the Cat, the studio chose Beans for the spotlight in the Looney Tunes series, starting with A Cartoonist’s Nightmare (1935). Other characters from Freleng’s original film, such as the twin puppies Ham and Ex and Oliver Owl, often appeared in King’s cartoons as supporting players.

When Tex Avery moved to the studio from Walter Lantz as a new director in 1935, he switched the stardom to Porky Pig whom he felt possessed more comedic potential with his timid nature and stutter. By comparison, Buddy and Beans were stale “good guy” characters, among the rest of many Mickey Mouse offshoots that bore no characteristics to make them unique. While Avery directed his own cartoons with Porky Pig, King handled a few, as well, including Fish Tales, Shanghaied Shipmates, Porky’s Pet and Porky’s Moving Day (all 1936). By the time these titles were released to theaters, King returned to the Disney studio by April 27th, 1936 as a director on the new series of films starring Donald Duck.

King’s first Donald Duck film, Modern Inventions (1937), which featured the earliest contribution in animation from Carl Barks, then an-inbetweener who sold gags to the Donald comic strip—a forerunner of Barks’ future in the development of the character in print media. For a decade, in collaboration with several story artists such as Barks, Harry Reeves, Chuck Couch, Homer Brightman, Ralph Wright and Roy Williams, King’s Donald films further defined Donald Duck’s pompous and hot-tempered personality, which ultimately eclipsed Disney’s own Mickey Mouse. King’s films also showcased other characters to co-star with Donald—Huey, Dewey and Louie in the screen adaptation of Donald’s Nephews (1938, based on a 1937 story in the Donald comic strip), the gluttonous Gus Goose in Donald’s Cousin Gus (1939), and the crystallized Daisy Duck in Mr. Duck Steps Out (1940, previously Donna Duck in 1937’s Don Donald).

With America’s involvement during World War II in the 1940s, King portrayed Donald Duck as a “sad sack” buck private under the command of Sergeant Pete in several films, starting with Donald Gets Drafted (1942). He continued to direct other standout entries in the series, including the Oscar-nominated Donald’s Crime (1945), Cured Duck (1945), Donald’s Dilemma (1947) and Donald’s Dream Voice (1948). The latter three titles are credited to Roy Williams for story. Williams often gave a better presentation in the storyboard sessions than the overall finished film, as Jack Kinney recalled: “He said, ‘Goddamn that Roy, he tells a story so goddamn funny up there, and then I put ‘em in the pictures and they’re not funny any more. Why did we even laugh?’ He thought, gee, this is a funny story, because everybody’s laughing—at Roy, they weren’t laughing at the story.”

Some sources believe Jack King “retired” from Disney in 1948, the year of his last directorial credit The Trial of Donald Duck. However, two different events contradict these claims: in 1946, facing financial troubles, Disney laid off 450 artists from the studio. Also, King’s supposed “retirement” does not fully coincide with the backlog of animated short cartoons at all the major studios, due to the labor strike and shortage at Technicolor affecting their release schedules. It could be assumed, though based on speculation, that King was a casualty of these layoffs, presumably to minimize costs and in effect, cut back on directorial units at the studio. King passed away in 1958 at Los Angeles—the cause of his death is unknown.

Some sources believe Jack King “retired” from Disney in 1948, the year of his last directorial credit The Trial of Donald Duck. However, two different events contradict these claims: in 1946, facing financial troubles, Disney laid off 450 artists from the studio. Also, King’s supposed “retirement” does not fully coincide with the backlog of animated short cartoons at all the major studios, due to the labor strike and shortage at Technicolor affecting their release schedules. It could be assumed, though based on speculation, that King was a casualty of these layoffs, presumably to minimize costs and in effect, cut back on directorial units at the studio. King passed away in 1958 at Los Angeles—the cause of his death is unknown.

Sorry to disappoint the devoted readers of my weekly columns, but I will be taking another, this time longer, break. I hope to resume writing in August, if not later. This will give me some time to write my upcoming book project based on my “Radio Round-Up” series of posts, and to work out my new job (and maybe an additional job, from the looks of things). Don’t worry, folks, I’m not fully gone — I will be back!

(Thanks to Michael Barrier, Didier Ghez, Joe Campana and Steven Hartley for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

That book project already peeked my interest.

Enjoy your break, Devon. Your columns have been great fun, and even very surprising for years now.

I’ve stated herein before how much I’ve gotten to like the BUDDY series and overall cartoon productions at Warner Brothers throughout the 1930’s. I have fond memories of seeing the BUDDY cartoons on TV. I’m sure that Jack King lent a lot of interesting effects and ideas to these cartoons. I also like “SHANGHIED SHIPMATES”. It is one of the stranger and darker cartoons to the early PORKY PIG series. Your columns, here, Devon, have been fun and informative, and I hope you don’t “lurk” too long. Good luck with your book; we need more of that history out there.

This book you speak of also has my curiosity. Ive long hoped for some sort of comprehensive guide to dated cultural references that appeared in classic cartoons. Looking forward to reading it.

These 1946 layoffs would coincide with the time that Fred Moore, Emery Hawkins, and Art Babbitt left the studio, right?

Actually, the layoffs took effect in mid-July 1946. I believe Art Babbitt voluntarily left the studio earlier in January ’46, while Disney fired Fred Moore in August. Not sure if it was due to Moore’s behavior or as part of the layoff, but understandably, it was a tough decision for him to make.

As for Hawkins, he certainly was a casualty of the layoffs. (Dave Smith told me he was let go from his third stint at Disney’s by July 26, 1946.)

PIQUED!

Color me interested!!

King irked Disney no end with his way of doing things, yet when he went to Sclessinger, he was a fountain of wisdom on the Disney method – go figure. And then Walt hired him back with promotion to director? Talent will out, I guess.